We Love You Bunny Summary, Characters and Themes

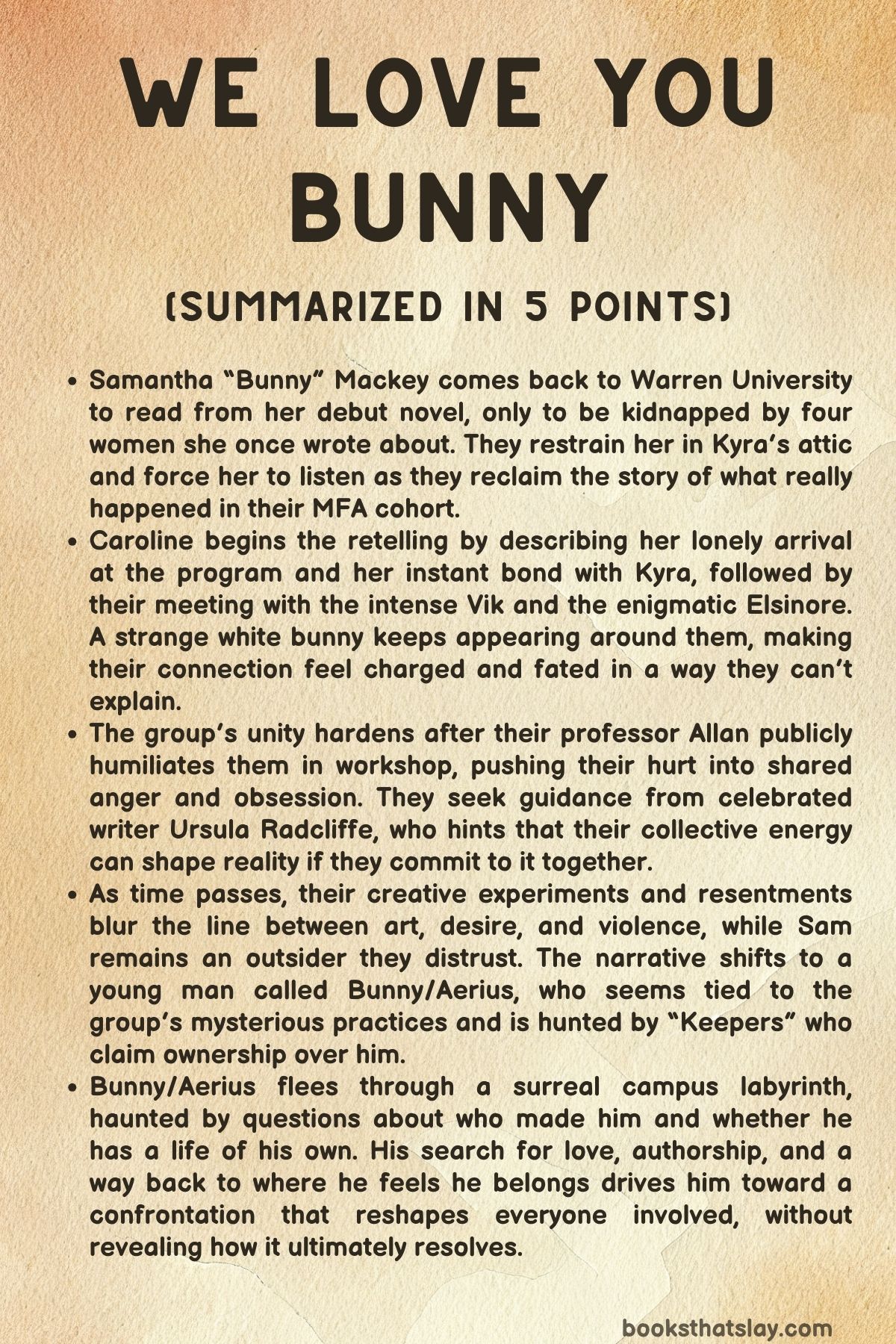

We Love You Bunny by Mona Awad is a dark campus novel that plays with fame, memory, and the stories people tell to survive each other. It opens years after an MFA program imploded, when Samantha “Bunny” Mackey returns to her old university to read from a debut book that recasts her former classmates as monsters.

The visit turns into a literal reckoning: the women she wrote about kidnap her and demand their version of events. What follows is a shifting, feverish account of how a fragile creative friendship became a closed circle, then a cultish force, and finally a mirror that broke everyone who looked into it. It’s the sequel to Bunny.

Summary

Samantha “Bunny” Mackey comes back to Warren University for a reading from her first novel. The book is a thinly veiled retelling of her MFA cohort, depicting four women as vicious, theatrical villains who once pursued her with an axe.

The event goes well enough, but afterward Sam feels the awkward weight of returning to the place she escaped. She drinks with old acquaintances, tries to stay polite, and tells herself she can leave campus behind again the next morning.

Instead, the four women she fictionalized—Caroline, Kyra, Viktoria, and Elsinore—approach her and offer wine. Sam accepts, perhaps out of bravado, perhaps out of guilt.

The drink is drugged. She wakes tied to a chair in Kyra’s attic, gagged, dizzy, and unable to move.

The women stand around her in rabbit masks and color-coded outfits, speaking in a shared, mocking rhythm. They congratulate her on publishing a book that made money off their pain, sneer at how she flattened them into caricatures, and remind her that the attic is where everything first tilted into violence.

They don’t plan to kill her, they say. They plan to reclaim the narrative.

One by one, they will tell their story, and Sam will listen, whether she wants to or not.

Caroline begins. Back in their first fall in the Narrative Arts MFA, she arrived from Virginia frightened and tightly wound, carrying a razor blade she used on herself when panic became too loud.

At the welcome party, the crowd of confident writers and professors overwhelmed her; she felt childish in her sky-patterned dress and white gloves and was close to slipping away to the bathroom to cut. Then she noticed another girl as isolated as she was: Kyra, small, red-haired, wearing a grass-patterned dress and white gloves that matched Caroline’s.

The similarity felt like a sign. They bonded instantly, swapping compliments and confessions about hating parties.

Kyra pulled Caroline toward a third student, Viktoria—Vik—thin, sharp-eyed, dressed in grungy plaid, eating pastries with feral focus. Vik spoke openly about wanting to make work that excited her, not work that behaved, and she hinted at a kind of art that mixed bodies, fantasy, and control.

Caroline was intimidated but fascinated. Across the tent, Caroline also saw a famous faculty writer, Ursula Radcliffe, speaking privately with a pale silver-haired student.

The pair looked at Caroline like they already knew her. Caroline felt jealous, pulled toward power she couldn’t name.

After the party, Kyra walked Caroline home, then brought her up to Kyra’s attic, describing it as a charged space where creation could happen differently. Later that night, the two met a white bunny on the path.

It stopped, stared at them, then hopped away. The encounter felt staged by fate.

They clutched each other’s hands hard enough to leave bruises.

The next morning they woke in Caroline’s apartment, oddly tangled and wearing each other’s dresses as if they had swapped during sleep. Caroline felt unsettled but also unable to break the new closeness.

They went to the first workshop together. Outside the Narrative Arts building, the bunny watched them again, this time near rose bushes, deepening Caroline’s sense that something had chosen them.

Inside the classroom sat the rest of the cohort: Vik, the silver-haired girl (later known as Elsinore), Sam, and Kyra. Everyone expected Ursula to teach, but a tall Scottish horror writer, Professor Allan, arrived instead, filling in while Ursula was away.

Sam lit up at Allan’s entrance. Caroline recoiled.

Allan started critiquing immediately, ripping into Caroline’s two-page story with cold precision. Her humiliation felt unbearable.

Without thinking, she pressed her finger into the razor in her pocket. Blood soaked her glove.

Kyra noticed and steadied her. Vik offered a crude, almost admiring comment.

Elsinore watched with a quiet, penetrating sympathy. When Allan asked for Sam’s opinion, Sam backed him, calling Caroline’s work too cute and artificial and advising her to be more “organic.

” Caroline felt the betrayal like a slap; in that moment Sam became an enemy.

After class Caroline fled with Kyra to the rose garden, shaking and furious. She ignored her mother’s calls, sobbed, and raged about Allan.

The pain twisted into a fantasy of revenge. She said she wanted to kill him.

Kyra, half teasing but half serious, asked if she should do it. Caroline said yes, and said they should do it together.

A white bunny appeared near a bronze hare statue, approaching instead of fleeing. Caroline lifted it, calling it Bunny, and as her tears and blood touched its fur, its eyes shifted from dark to an impossible sky-blue.

The change stunned her and Kyra, and for a heartbeat their despair evaporated, replaced by a sense that they had made something unreal happen. Vik and Elsinore ran over, and the four girls ended up holding each other, all crying, all shaken by the bunny’s eyes.

Then the bunny slipped away into the roses.

Kyra interrupts Caroline’s version to claim she saw the bunny first and that its eyes changed only when both of them held it. Their disagreement shows a pattern that will haunt them: each remembers the same moments as proof of different truths.

Still, in the glow of that afternoon, they returned to Kyra’s attic holding hands as if they were a single creature.

In the attic they drank absinthe and tried to explain what happened. Vik and Elsinore suggested a campus experiment, refusing to grant the moment meaning.

Kyra couldn’t let it go. Elsinore pivoted back to Allan, framing his critique of Caroline as violence against all of them and predicting he would destroy each of their voices.

They decided to contact Ursula Radcliffe for help—and to do it without Sam, who had sided with Allan and felt unsafe to include.

Weeks passed. Allan examined each of their stories and, after every session, one of them broke down in the rose garden.

Their shared humiliation fused them tighter. Kyra’s situation grew more complicated because Allan praised her work, which made the group suspicious and made Kyra defensive.

During one of Elsinore’s blowups, the blue-eyed bunny reappeared with a faint trace of Caroline’s blood still on its fur, then vanished again when their phones buzzed with Ursula’s reply. Ursula invited them to her house.

At Ursula’s home, they praised her, confessed Allan’s cruelty, and begged for rescue. Ursula listened kindly but refused to take over the workshop.

She advised them to use their wounds as fuel and hinted that their special power lay in their collective bond. She asked where Sam was.

When they explained they didn’t trust her, Ursula didn’t argue. She only smiled in a way that suggested she understood what a closed circle can become.

Leaving Ursula’s porch, the four repeated her words like a spell. They went to a tiny café called Mini, turning the idea of a shared creative crucible over and over.

Elsinore insisted they already had it and told the others to follow her lead. Kyra followed too, even while jealousy bubbled in her—she felt Caroline slipping away toward Vik and Elsinore, and she feared losing the first person who had ever mirrored her so completely.

Their unity tightened into something hungry.

Elsewhere on campus, a narrator who seems to be one of the group’s creations walks with an axe hidden under his coat. He is in love with a boy named Jonah, and he believes he must find and kill Allan to protect the women who made him.

Posters announce that a student, Tyler Fields, is missing and presumed murdered. Jonah points out that the narrator was near the frat house at the time and resembles the face circulating in news reports.

Jonah still kisses him, tells him to stay quiet about the axe, and goes to class with Sam. Watching Jonah’s interest in Sam breaks the narrator’s focus.

He wanders off, forgets his mission, and drifts into town.

At a highway truck stop bar, drunk and despairing, he confesses he is looking for Allan and already killed the wrong one. Two men laugh and say they are Allan.

In a blur of rage and confusion, he beheads them. Their bodies are gone afterward, leaving him unsure what is real.

He collapses outside, sick with violence and heartbreak.

Four trench-coated poets find him and drag him to their apartment, “Oblivion. ” They call him their Muse, record his words, feed him and keep him half-drunk.

Rumors spread about an axe killer who looks like a movie star; the poets eye him warily but refuse to let him go. The days smear together until a mob of arts students storms “Oblivion” demanding action against axe violence.

The poets deny knowing anything. The Muse listens, hollowed out by being used again.

Chaos erupts later at a theater showcase when rabbits flood the room. In the confusion, the Muse—also called Aerius or Bunny—grabs his book from a controlling figure called Mother and runs into the Narrative Arts building.

The hallways feel endless, doors glowing with ominous titles. He finds a door marked “Hall of Infinite Reflection” and steps inside because there is nowhere else to hide.

The chamber is filled with mirrors that replicate him endlessly: battered face, bleeding chest, book clutched to his heart. He realizes he is not unique; he is a made thing, reflected and owned.

The Keepers—the women who created him—arrive and can’t identify which reflection is real. They whisper that they love him and that he belongs to them.

As they press in, chanting love as entitlement, the mirrors begin to crack.

The Keepers descend into frenzy, kissing, stabbing, and clawing at their own reflections, desperate to reclaim him. The Murder Fairy, one of their number, decides the only way to save what’s left of them is to destroy the illusion.

She swings a storm of axes into the mirrors. The reflections shatter.

Glass pours down, cutting the Keepers and ending their infinite ownership. Bunny stays standing, sees an EXIT sign behind the ruined mirror wall, and escapes into the night.

Outside, he tries to use the book as a way back to a place he believes he belongs, but the last page contains only his life up to this moment, written in his own hand. The failure forces him to admit the voice guiding him was his own mind.

He is stranded in the world he wanted to flee.

Jonah appears, tender and real enough to quiet Bunny’s panic. He kisses Bunny, notices his wound, and asks what happened.

Bunny can’t explain. He only wants Jonah close.

They run to a grassy space near the Philosophy building. Jonah apologizes for choosing his writing over Bunny before and says Bunny matters more.

A rabbit named Leonard appears, tugging Bunny back toward the life he is leaving behind. Bunny gives Jonah the book, sensing it may be meant for someone else.

Then he kisses Jonah goodbye and walks away.

On Philosopher’s Walk, Bunny sets down Pony—his imagined companion—accepting that even unreal love can be true to him. A second shadow joins his path: Tyler, the boy he killed earlier, alive again but disoriented, afraid of dying into nothingness.

Bunny comforts him by repeating the idea that there are many ways home. Holding hands, they begin to hop forward together.

As they move, their bodies and shadows subtly shift, hinting that transformation is possible, and that whatever home is, it might be found not by being owned, but by choosing to keep going.

Characters

Samantha “Bunny” Mackey (Sam)

Sam sits at the tense center of We love you bunny Final as both creator and accused. Returning to Warren University for a reading, she is already split between her present identity as a newly published author and the past she tried to control through fiction.

Her novel’s portrayal of her former cohort as monstrous villains reveals her need to frame trauma in ways that keep her safe and legible to herself, but it also exposes her blindness to how powerfully she can injure others with narrative. When abducted, drugged, and forced to listen, her loss of bodily control mirrors her loss of authorial control: she is no longer the one who decides what the story means.

Sam’s instinctive skepticism and sharpness—seen earlier in her siding with Allan’s critique—mark her as someone who survives by distance, judgment, and refusing softness, yet those same traits isolate her and make her an easy target for collective resentment. She is both victim and aggressor, and the book keeps her in that uncomfortable double role, showing how storytelling can be a weapon as real as the axe she once metaphorically handed the others.

Caroline / Coraline (“Cupcake”)

Caroline is introduced through vulnerability that is simultaneously tender and dangerous. Her social anxiety, self-harm, and desperate craving for belonging make her exquisitely receptive to the cohort’s later mythmaking.

She begins the program feeling small, “cute,” and ashamed of that cuteness, which makes Allan’s brutal critique land like a confirmation of her worst private beliefs. Yet her fragility is paired with a latent intensity: her sudden, half-serious wish to kill Allan is the first explicit articulation of violence, and it becomes the seed of the group’s transformation.

Caroline is also deeply attuned to symbols and synchronicity—the matching gloves, the swapped dresses, the bunny’s appearance—so she becomes a natural conduit for the idea that their bond is fate or magic. Her narration shows how memory becomes self-defense; she insists Sam “got everything wrong,” not just to correct facts but to reclaim identity from Sam’s version.

Caroline’s sweetness is therefore not superficial; it is a style of survival that can evolve into ferocity once it is threatened.

Kyra

Kyra functions as the emotional engine of the original quartet, someone who both nurtures and subtly orchestrates closeness. She gravitates to Caroline instantly, mirroring her with matching gloves and dresses, and she creates intimacy quickly—inviting herself over, leading Caroline to the attic, positioning that space as sacred for making.

Her version of events shows a need to be recognized as the true witness and co-author of their origin story, suggesting that for her, belonging depends on narrative credit. Kyra’s jealousy appears early, especially as Caroline begins leaning toward Vik and Elsinore, which hints at Kyra’s fear that affection is always precarious and must be held tightly.

Her focus on the bunny’s meaning, even when others dismiss it, reveals her desire for the world to be enchanted in a way that validates the intensity she feels. Kyra is not merely a follower; she is a believer, and belief is her power.

Viktoria (“Vik”)

Vik arrives with a brash, bodily confidence that disrupts the program’s polished literary intimidation. She openly frames art as something erotic and hybrid, refusing shame about what excites her, which makes her both magnetic and unsettling to Caroline and Kyra.

Her appetite—literal in the pastry scene and metaphorical in her creative ambition—codes her as someone who consumes experience without apology. That stance becomes crucial to the group dynamic: Vik offers a model of how to turn humiliation into fuel, how to transmute pain into something thrilling instead of merely endured.

She tends to rationalize the uncanny bunny incident as a possible experiment, suggesting she is less mystic than the others, but she still participates fully in the collective fever around Allan. Vik’s charisma helps solidify the quartet as a force, and her willingness to chase intensity pushes them toward extremes.

Elsinore

Elsinore’s presence is cool, sharp, and quietly authoritative, the kind of person who seems to understand the room before anyone else. From early on she offers silent recognition to Caroline, hinting at a private intensity beneath her composure.

She quickly reframes Allan’s cruelty not as a personal failing for each of them but as an ideological assault on their collective worth, which allows the quartet to unite around a shared enemy. Her certainty that they must find their “creative crucible” makes her a kind of prophet for the group, someone who gives shape to their rage and converts it into mission.

Elsinore is also a gatekeeper of meaning—she acts as though she already grasps what Ursula is implying—so her authority is rooted not in overt dominance but in interpretive confidence. She is the strategist of emotional violence, turning feeling into direction.

Ursula Radcliffe

Ursula stands as the remote, mythic figure of artistic legitimacy the young writers hunger for. She is idolized from the start, and her attention is treated as almost supernatural, so her eventual meeting with the quartet becomes a ritual more than a conversation.

Ursula offers sympathy without rescue; she refuses to replace Allan and instead instructs them to “tap the wound,” reinforcing the romantic idea that suffering is necessary for art. Yet she also subtly flatters their unity, implying they have special collective power and could change reality through working together.

Her ambiguity is the point: she is both mentor and instigator, the adult who legitimizes their sense of exceptionality while keeping her own project hidden. Ursula embodies the MFA-world contradiction of nurturing talent while feeding it to cruelty, and her influence lingers like a spell the quartet cannot tell is blessing or curse.

Professor Allan

Allan is a catalytic antagonist, less a fully explored person than a force of institutional violence. His arrival disappoints the cohort’s expectations of Ursula and immediately sets a tone of domination through critique.

By tearing into Caroline’s “cute” story and drawing Sam’s public agreement, he engineers humiliation as spectacle. Yet his role is complicated by the fact that he praises Kyra’s work, revealing that his cruelty is not evenly distributed but strategic in the way it reshapes hierarchy within the cohort.

Allan represents the gatekeeping logic of literary culture: the idea that art must be purified through pain, and that authority proves itself by the ability to wound. Whether or not he deserves the quartet’s later fantasies, he undeniably creates the emotional conditions that make those fantasies feel inevitable.

The Conjured Narrator / Aerius / Bunny (the male “Muse”)

This narrator is the story’s living metaphor for what happens when people attempt to manufacture beauty, devotion, or art through possession. He moves through the world feeling half-real, as if he has been summoned into being rather than born, and his anxiety about the hidden axe mirrors his dread that his life is already scripted by others.

His love for Jonah anchors him in yearning for authentic connection, but he is constantly pulled back into the logic of being owned—first by the Keepers who “conjured” him, then by the trench-coated poets who kidnap him as their Muse. The Hall of Infinite Reflection sequence pushes his identity crisis to a breaking point: seeing endless versions of himself makes him understand that he is not singular in their eyes but reproducible, disposable.

His escape is not just physical but existential, a refusal to remain someone else’s story. Even his relationship to the magical book is unstable—when it writes his life up to the present, it confirms his fear that he is trapped inside narrative machinery.

He embodies the book’s deepest question: can anyone be loved without being consumed?

Jonah

Jonah is the gravitational pull of the conjured narrator’s emotional world, and his inconsistency is part of his realism. He is affectionate and reassuring, kissing the narrator and insisting on trust, but he is also easily entranced by Sam and by literary charisma, drifting toward whatever seems most alive in the moment.

To the narrator, Jonah becomes both salvation and betrayal, evidence that love exists and proof that it can vanish without warning. When Jonah reappears later and chooses Bunny over poems and Poet Tree, he functions as a corrective to the world’s predatory creativity—he asserts that a person matters more than a page.

Jonah’s gentleness, his readiness to read Bunny’s book and admire it, positions him as someone capable of loving art without using it as ownership. He is the possibility of care that does not require capture.

Tyler Fields / Wrong Allan / the one-eyed boy

Tyler operates as a shifting figure of guilt and reality fracture. First seen as a missing student and then as the patched-eye bunny echo, he becomes proof that the narrator’s violence is both real and unreal, something the world cannot confirm because bodies do not stay put.

As “Wrong Allan,” he represents the horror of misdirected rage—someone killed in the fog of obsession and symbolism. His later reappearance, alive but stranded between states of being, makes him a companion in liminality; he is what Bunny might become if he cannot find a way home.

Tyler’s fear of dying into nothingness gives emotional weight to the book’s metaphysical play: underneath the surrealism is a raw terror of meaninglessness. When Bunny takes his hand, Tyler becomes less a victim and more a fellow traveler toward transformation.

The Keepers (Goldy Cut, Murder Fairy, Insatiable, Mind Witch)

The Keepers function as a collective predator masked as love. Their individual names read like archetypes of appetite and manipulation, suggesting they are less people than embodiments of the ways artists justify control.

They speak of conjuring Bunny as if he is an artwork, not a person, and their readiness to “make another” if they lose him exposes the chilling logic of replacement. Their hunt through the Narrative Arts building shows love curdled into entitlement; they call him “theirs,” insisting belonging equals possession.

The moment when the Murder Fairy destroys the mirrors is revealing: even within this predatory collective, a line is crossed where love understood as ownership becomes self-destructive. The Keepers dramatize the theme that adoration can be just another form of violence when it denies the beloved’s autonomy.

The Trench-Coated Poets (Colby, Matthias, Gunnar, and their leader)

These poets are a darker mirror of the Keepers: another collective that turns human beings into raw material. They kidnap the narrator not out of hatred but out of aesthetic hunger, declaring him their Muse and stripping him of privacy by recording his every mutter.

Their apartment “Oblivion” is aptly named, because his time there dissolves his spirit into drunken passivity. Their internal argument about whether he is the axe killer shows their moral slipperiness; they are willing to exploit his mystique while disavowing responsibility for his harm.

They represent a different mode of artistic theft: not conjuring a person into being, but draining an existing person until only usable lines remain.

Pony and Leonard (the rabbits as companions and symbols)

Pony, the toy pony voice that urges Bunny onward, is a tender portrait of self-created comfort. Bunny ultimately recognizes Pony as imagined, but the acceptance is loving rather than humiliating—an acknowledgment that inner companions can still be real in the way they sustain us.

Leonard, the rabbit who reappears near the end, is the opposite: a living tether to the world Bunny fled and a reminder that escape does not erase origin. Together they mark the spectrum of the book’s animal symbolism, where rabbits are at once omens, doubles, and guides.

They are not just cute motifs but carriers of fate, fear, and the possibility of another way of being.

Themes

Storytelling as Possession and Reclamation

From the opening setup, the plot treats storytelling not as a harmless retelling but as an act that can steal, distort, or overwrite lived experience. Sam’s debut novel, which turns her MFA cohort into monsters, becomes a kind of second violence: the women feel used, caricatured, and publicly fixed into roles they did not choose.

Their abduction of Sam is not framed as random revenge but as an attempted correction of power. They force her to listen to “their story properly,” which immediately raises the question of who gets to define reality once it has been turned into art.

The attic scene suggests that narratives are battlegrounds: the group is masked, speaking in a collective voice, and holding an axe as if the language of art and the language of threat are no longer separable. Each woman’s insistence on her own version of events, especially the split between Caroline’s and Kyra’s memories, shows how unstable truth becomes when filtered through desire, hurt, and self-mythology.

Importantly, the novel does not simply say one account is right and the other is wrong. Instead, it shows that control over a story can function like control over a body.

To be written about is to risk being trapped inside someone else’s gaze; to write back is to fight for your own shape. This dynamic becomes even more literal with Bunny/Aerius, whose very existence seems to depend on other people “conjuring” him into being.

He is treated as a Muse and as property, recorded and drained by the poets, loved in a way that demands he stay useful to them. The Keepers’ chant of love while they close in on him in the mirror hall turns affection into a cage: “we made you, you belong to us” is the core logic of exploitative storytelling.

Yet Bunny’s escape and his final decision to hand the book to Jonah suggest another possibility. A story can also be released.

When he realizes the book may not be for him, he accepts that authorship sometimes means letting meaning travel beyond the author’s control. The theme lands on a sharp paradox: storytelling can be a form of domination, but it can also be a route to freedom when ownership is surrendered rather than enforced.

Collective Identity, Intimacy, and the Hunger to Merge

The early formation of the four-woman unit is saturated with longing for sameness. The matching gloves, the swapped dresses, the hand-holding, and the repeated appearance of the bunny all build a sense that belonging is not just social but almost chemical.

Caroline arrives anxious, self-harming, and desperate to be seen without being judged; Kyra arrives equally frightened and quickly offers closeness so total that it unsettles Caroline. Their bond is immediate, and the narrative stresses mirroring: they recognize themselves in each other before they know each other’s facts.

When Vik and Elsinore join, the group becomes a refuge against humiliation and loneliness, but also something more consuming. Their shared breakdowns after Allan’s critiques don’t merely create friendship; they create a fused identity shaped by a common enemy and a common wound.

The bunny’s eyes turning blue only when two of them hold it at once becomes a symbolic stamp of this merger: their power seems to activate through combination, not individuality. Yet the novel keeps showing the cost of that fusion.

Kyra’s interruptions of Caroline’s story illustrate that even in a tight collective, each person wants her own centrality. Jealousy appears not as a side emotion but as proof that merging does not erase the self; it heightens the fear of being replaced inside the group.

The collective voice in the attic similarly performs unity while masking internal fractures. They speak as “we,” but they also demand turns, spotlight, validation.

On the other side of the plot, Bunny/Aerius experiences forced merging in a darker register. The Keepers and the poets want him as a shared resource, a living generator of their art.

In the mirror hall, his infinite reflections reduce him to endlessly repeatable versions of the same thing, implying that a collective can flatten a person into a function. The Keepers’ hysteria at not being able to tell which Bunny is real shows a terror of individuality: if he can be singular, he can leave.

Bunny’s escape breaks the collective spell, but the theme doesn’t merely condemn groups. It shows why the desire to merge is so strong: it promises safety, magic, and erasure of pain.

The tragedy is that the same desire can turn love into surveillance and belonging into captivity. By the end, Bunny walking with Wrong Allan/Tyler toward an unknown home hints at a quieter kind of togetherness, one that accepts difference and uncertainty instead of demanding total fusion.

The theme therefore explores collective identity as both medicine and poison, depending on whether it allows the self to breathe.

Humiliation, Self-Harm, and the Alchemy of Pain into Art

Pain is not presented as a background condition; it is the fuel everyone is trying to shape. Caroline’s razor in her pocket makes her vulnerability constant and physical.

Allan’s critique is experienced as a public stripping, and her bleeding through her gloves turns emotional humiliation into literal injury. The text repeatedly links workshop culture with assault, not because criticism is inherently cruel, but because for these characters the classroom is a stage where worth is decided and shame becomes identity.

The rose garden meltdown and the group’s repeated post-workshop collapses show how humiliation can be addictive in a twisted way: it hurts, but it binds them, gives them a reason to exist together, and offers a clear villain to blame. Ursula’s advice to “tap the wound” gives institutional blessing to this logic.

She does not comfort them by denying pain; she instructs them to use it. Her stance reflects a common artistic myth that suffering is necessary for greatness, and the cohort’s eagerness to believe her shows how seductive that myth can be when you feel small.

Yet the narrative keeps asking what this myth costs. Caroline’s self-harm is not glamorized; it is framed as a habit of redirecting outer cruelty inward because it feels controllable.

Her fantasy about killing Allan is born from humiliation so intense it seeks an outlet beyond words. The bunny’s transformation during her blood-soaked grief offers a momentary miracle that seems to reward pain with wonder, reinforcing the danger of thinking anguish is a portal to power.

Bunny/Aerius later embodies another angle of the same theme. His mission to kill Allan, his drunken confession, and the possibly unreal beheadings at the truck stop show how pain can warp perception into violence.

The uncertainty about whether bodies vanish suggests that when suffering becomes unmanageable, reality itself loses coherence. Even in the poets’ apartment, Bunny is drained as they harvest his misery for their scripts, again turning pain into a commodity.

The protest group Artists Against Axe-Related Violence parodies this circulation of trauma: they stage violence as performance because actual violence has already become narrative rumor on campus. Across these threads, the theme argues that pain does generate stories, but not cleanly and not safely.

It can create solidarity, magic, and art, but it can also lock people into repetitions of harm, making them believe they must bleed to be real. The novel’s tension lies in refusing to offer a neat cure.

Instead, it shows characters trying, sometimes desperately, to turn humiliation into meaning, while always risking being consumed by the very wounds they are told to use.

Love as Devotion, Dependency, and the Refusal to Let Go

The word “love” in this story is both promise and threat. The Keepers insist they love Bunny while hunting him and attempting to reclaim him, making clear that affection here is not separate from ownership.

Their love is collective, performative, and conditional on his usefulness as a creation they can control. In the mirror hall, their chant of love escalates into self-destruction: they kiss reflections, stab glass, and collapse into frenzy because love has become a justification for possession.

The line about killing darlings before they destroy you captures the theme’s core insight: what people call love can become a predator if it refuses to recognize the beloved as free. The cohort’s attachment to each other exists on a similar spectrum.

Their intimacy is tender in its origins—sleeping beside each other, sharing tea, walking hand in hand—but it is also irresistible, demanding, and jealous. Kyra’s need to be needed, Caroline’s craving for mirroring, Vik’s seductive boldness, and Elsinore’s radical certainty all feed a love that wants to absorb rather than accompany.

Sam’s exclusion is part of this logic too: once she sides with Allan, trust collapses into exile, as if love inside the group permits no ambiguity. Romantic love offers a counterpoint but not a simple alternative.

Bunny’s devotion to Jonah is genuine, softening the story with moments of warmth, yet it is also fragile and easily displaced when Jonah becomes enthralled by Sam or by poetry. Bunny’s heartbreak is not just jealousy; it is the terror of disappearing from someone else’s story.

When Jonah later returns to him in the alley, apologizing for choosing writing over Bunny, the scene suggests that love can change when it stops treating art or ambition as a rival to human presence. Jonah’s tenderness, his request to read the book, and Bunny’s willingness to hand it over indicate a shift from possessive attachment to mutual recognition.

Still, the theme doesn’t idealize this resolution. Bunny doubts Jonah’s reality, unable to trust love after being repeatedly treated as an object.

Even accepting Pony as imagined shows how the mind clings to love-figures for survival, whether or not they are “real. ” By ending with Bunny and Wrong Allan/Tyler hopping together toward an uncertain home, the narrative suggests that love may not always look like rescue or permanence.

Sometimes it looks like companionship in uncertainty, a shared movement without guarantees. In that sense, the theme maps a wide emotional terrain: devotion can nurture, dependency can strangle, and letting go can be the most loving act of all.

Reality, Fantasy, and the Instability of the Self

Nothing in this plot rests safely on a single plane of reality. The bunny with changing eyes, the idea of being “conjured,” the vanishing bodies at the truck stop, the hall of infinite reflections, and the book that writes itself in real time all create a world where perception is never fully trustworthy.

This instability is not just a stylistic trick; it is tied to identity. Caroline’s early self is already split—publicly timid, privately bleeding—so the surreal events around her read like externalizations of inner fracture.

The bunny appears at moments of extreme emotion, as if the world itself is responding to psychic need. The cohort’s belief in collective magic grows precisely because reality feels hostile; fantasy becomes a shelter they can step into together.

Yet belief in magic also allows responsibility to slip. If wonders are happening, then maybe violence is fated, maybe cruelty is part of a ritual, maybe the self is not entirely accountable.

Bunny/Aerius experiences this more sharply. He perceives mission, love, and threat through a haze of uncertain memory and possible past lives.

His killings may or may not have happened; the text keeps him, and the reader, in a state where guilt and hallucination blur. This blurring mirrors his own status as possibly created rather than born.

When the Keepers talk about making “another” like him, they treat selfhood as reproducible material, not sacred singularity. The mirror hall literalizes identity crisis: seeing infinite copies of himself does not make Bunny feel amplified; it makes him feel manufactured and trapped.

His terror stems from the possibility that he is nothing more than a reflection of someone else’s desire. The book is posed as an escape route, a doorway to a world where he “belongs,” but when he discovers it has only written his life up to this instant, the fantasy collapses into the stark fact that no text can guarantee home.

That moment grounds the theme: stories and imagination can sketch possibilities, but they cannot always deliver a stable self. Accepting Pony as imagined while still loving him reflects a mature, painful reconciliation with uncertainty.

The novel suggests that identity is built in negotiation between internal fantasy and external reality, and that when either side becomes absolute, the self fractures. The final movement toward an unknown way home does not solve the instability; it embraces it.

Bunny’s body and shadow beginning to change hints that the self is not a fixed object but a process, always becoming, always slipping between what is real, what is desired, and what is narrated.