We Who Wrestle with God Summary and Analysis

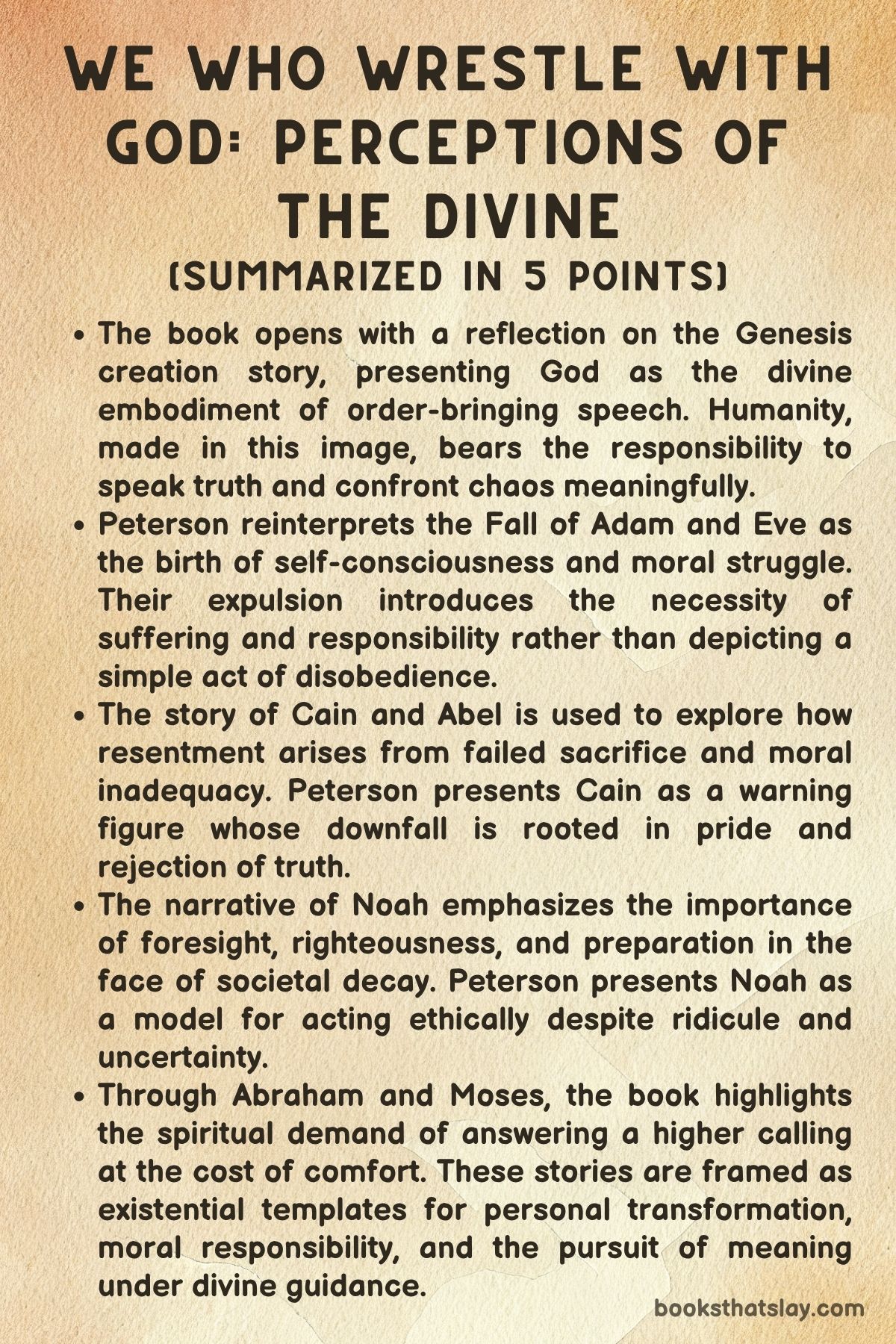

We Who Wrestle with God by Jordan Peterson is an interpretive journey through the Book of Genesis, treated not as literal scripture nor myth, but as a profound psychological and philosophical blueprint. Drawing on archetypes, symbolic language, and theological motifs, Peterson unpacks Genesis to explore what it reveals about the human condition—our morality, our social structures, and our confrontation with chaos.

Far from a conventional biblical commentary, this work attempts to reconcile modern psychological insight with ancient wisdom, arguing that the stories of Adam, Eve, Abraham, Jacob, Moses, and others represent universal struggles with pride, identity, suffering, transformation, and the sacred. Through this lens, Peterson contends that Genesis offers not outdated dogma, but an essential guide to responsible and meaningful living in a fragmented modern world.

Summary

We Who Wrestle with God opens by reinterpreting the Genesis creation story as a symbolic map for understanding human consciousness and moral agency. Peterson frames God not merely as a supernatural being but as consciousness itself—an active force that brings order from chaos.

The divine act of separating light from darkness, land from sea, and naming creation is mirrored in the human ability to categorize, judge, and act. The capacity for speech, discernment, and decision-making reflects the divine image in which humans are made.

For Peterson, this divine image grounds human dignity and rights and serves as the foundation for Western civilization’s moral architecture.

The Genesis narrative is then used to introduce Adam and Eve not simply as the first humans but as archetypes. Adam represents the conscious agent who names and structures reality, while Eve is symbolic of what lies outside known order—intuition, sensitivity, and emerging awareness.

Rather than being a secondary figure, Eve challenges Adam and extends the moral domain into the unknown. Their fall, commonly portrayed as disobedience, is interpreted as a prideful overreach: Eve believes she can redeem even the serpent; Adam chooses her over divine command.

This act reflects a common human tendency to violate sacred boundaries out of misplaced loyalty or the illusion of control. The consequence of their decision—suffering, shame, and self-consciousness—marks the beginning of the human journey toward redemption through humility, responsibility, and spiritual realignment.

The narrative then broadens to a discussion of the fall’s implications. Self-consciousness is identified as the moment when humans become aware of death, sin, and the limits of their power.

This awareness, while tragic, is also a necessary step toward maturity. Suffering becomes not just a punishment but a precondition for moral growth.

Peterson highlights how the archetypal masculine desire to control and the archetypal feminine desire to nurture can become distorted into ambition and narcissism when disconnected from higher purpose. Both Adam and Eve fall through pride, but their paths to redemption lie in the acceptance of responsibility, truth, and sacrifice.

From Adam and Eve, the book shifts to the patriarchal narratives—especially those of Abraham, Sarah, and Jacob. Abraham is portrayed as the model of faith and long-term vision.

His life becomes a testament to the necessity of disciplined sacrifice, trust in divine order, and the courage to pursue the unknown. Peterson contrasts Abraham’s commitment with modern cultural tendencies toward short-term gratification and hedonism.

He warns against the dangers of personality types that manipulate and exploit others—particularly in sexual relationships—at the expense of integrity and long-term fulfillment.

Sarah’s transformation from barrenness to motherhood is symbolic of the power of faith to animate what seems lifeless. Likewise, the story of Jacob wresting his identity from struggle demonstrates the internal battle every person must endure to become who they are meant to be.

Jacob’s deception, exile, and eventual reconciliation represent stages of psychological development, requiring the death of the immature self and the painful birth of a mature identity. His transformation into Israel, the one who wrestles with God, becomes the book’s central metaphor.

Throughout these stories, Peterson emphasizes that real transformation always requires sacrifice. This includes not only giving up what is comfortable but also letting go of falsehoods and attachments that impede moral and psychological growth.

Circumcision, for instance, is treated as a symbol of the commitment to restraint and alignment with the divine. The repeated theme is that sacrifice, while painful, is the price of becoming something greater.

The narrative deepens as it engages with the stories of Moses, Aaron, and the Israelites in the wilderness. Peterson analyzes Moses’s disobedience—not asking God for water but instead striking the rock—as a moment of pride and self-aggrandizement.

For this lapse, even Moses is denied entry into the Promised Land, showing that leadership must be guided by humility. Peterson suggests that spiritual authority is not about power but about faithful obedience, even when it is inconvenient or difficult.

The episode of the bronze serpent in the desert serves as another potent symbol. When the Israelites are plagued by venomous snakes, God instructs Moses to create a bronze serpent and lift it on a pole.

The people must look upon it to be healed. Peterson interprets this as an invitation to confront suffering and fear head-on.

Healing comes not by avoidance but through conscious confrontation. This paradox—that salvation often involves facing what one most fears—recurs throughout the text.

Peterson also explores the cultural implications of these stories. He discusses the moral collapse of Sodom, not only in terms of sexuality but in terms of its rejection of hospitality—a basic social obligation.

Abraham’s act of welcoming strangers contrasts with Sodom’s violence, and this contrast is used to critique contemporary political polarization and social fragmentation. For society to function, there must be trust, openness, and mutual responsibility, grounded in shared moral commitments.

The story of Isaac’s near-sacrifice is positioned as the apex of the book’s exploration of faith and responsibility. Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his beloved son, though emotionally wrenching, demonstrates ultimate trust in divine wisdom.

Peterson uses this moment to warn against possessive parenting and to advocate for allowing children to become independent moral agents. Sacrifice is shown not as loss but as transformation—the letting go of what is most precious in the pursuit of what is most right.

The final narrative arc follows the journey from Numbers to Jonah. Peterson interprets Moses’s death outside the Promised Land as the acceptance of one’s limits in the service of something greater.

Jonah’s story, meanwhile, becomes an illustration of psychological resistance to divine command. Fleeing from God, Jonah finds himself in the belly of a fish, symbolizing a death and rebirth cycle.

His reluctant obedience ultimately brings salvation to Nineveh, yet his bitterness reveals the human difficulty in embracing grace and mercy for others—especially enemies.

Throughout these stories, Peterson emphasizes that the divine voice must be answered, whether it appears as conscience, truth, or suffering. The call to humility, sacrifice, and responsibility is not optional—it is the path to meaning, integrity, and communal survival.

Pride, avoidance, and falsehood lead to chaos and collapse, while reverence, honesty, and courage open the door to renewal. In this way, We Who Wrestle with God offers a reinterpretation of ancient texts that seeks to awaken the reader to the sacred dimensions of ordinary life and the enduring challenge of becoming truly human.

Characters

God

In We Who Wrestle with God, God emerges not as a remote, impersonal architect of the cosmos but as a profoundly conscious and dynamic spirit who acts intentionally and relationally. Jordan Peterson portrays God as the ultimate personification of order-making consciousness, a force that confronts chaos and brings forth structured reality.

This divine process is not static; it is active, moral, and creative. God’s actions in Genesis—separating light from darkness, land from water, naming the components of creation—are not simply cosmological gestures but symbolic representations of the human capacity for discernment and moral judgment.

God is both transcendent and immanent, embodying the Logos that breathes meaning into the void. God’s role is not merely to create but to call forth value from potentiality, a process echoed in human creativity and responsibility.

By making humans in His image, God imbues them with the sacred capacity for consciousness, speech, and moral action, establishing the moral foundation of the Western worldview. God’s commands, boundaries, and judgments are not arbitrary but necessary structures to contain chaos and promote growth.

Thus, He serves both as an ideal toward which we strive and as the ever-present voice of conscience demanding accountability, humility, and sacrificial order.

Adam

Adam, in Peterson’s analysis, is the archetype of masculine consciousness—rational, naming, and ordering. His role in Genesis is not merely as the first man but as the prototype of the human mind that confronts chaos and structures it through categorization and speech.

Adam’s task of naming the animals is emblematic of this impulse to define, delimit, and thereby make habitable the unknown. Yet Adam’s character is not without flaw; he becomes passive when moral courage is required.

In the Genesis fall, Adam’s great failure is not just in eating the forbidden fruit but in his willingness to subordinate divine command to relational harmony. He does not speak when he should, failing to uphold the boundary established by God.

His sin is one of abdication, an unwillingness to take responsibility in the face of temptation and moral ambiguity. This silence signifies the corruption of authentic authority.

Adam’s journey, therefore, reflects the perennial male challenge: to balance mastery with humility, and to exercise moral strength without descending into tyranny or cowardice. He is both the architect of order and its potential betrayer, capable of greatness when aligned with the divine Logos and capable of ruin when seduced by pride or appeasement.

Eve

Eve represents the archetypal feminine in We Who Wrestle with God, embodying sensitivity, receptivity, and the capacity to engage with what lies beyond the current boundaries of structure. Her emergence from Adam is not a mark of subordination but a symbolic representation of differentiation and complementarity.

She draws attention to what Adam’s order overlooks—the emotional, the marginal, the emerging. Eve’s role is not simply to support but to challenge, to provoke integration of the unacknowledged.

She symbolizes care, intuition, and the transformative potential of attention to the vulnerable and unknown. However, her character is also shaped by pride—a belief that through compassion alone she can redeem even the poisonous.

This leads her to take the fruit, an act framed not as naive curiosity but as a tragic overreach. Her presumption that she can bear divine knowledge and encompass even the serpent without consequence reflects a distortion of her strengths into narcissism.

Yet Eve is also the first to suffer the costs of this presumption—self-consciousness, shame, pain. Her role becomes one of insight and suffering, and her character arc reveals the power and peril of feminine intuition when detached from humility and reverence.

Eve ultimately illustrates the burden and dignity of perceiving more than can be immediately ordered.

Abraham

Abraham stands as a towering figure of faith and moral ambition in We Who Wrestle with God. He is the man who ventures into the unknown not out of compulsion but by divine calling, sacrificing comfort and certainty for the sake of a higher destiny.

Abraham’s greatness lies not merely in his obedience but in his active wrestling with God’s demands. His journey is one of transformation—Abram becomes Abraham only after entering into a covenant that reshapes his identity and destiny.

Peterson sees Abraham as the embodiment of long-term vision, someone who commits to generational good rather than immediate gratification. His defining moment, the near-sacrifice of Isaac, is read as the ultimate test of faith, a willingness to relinquish even that which he loves most in order to remain faithful to the highest good.

This act is not portrayed as divine cruelty but as the pinnacle of moral seriousness—the refusal to become the devouring parent who controls rather than liberates. Abraham models the virtue of delay, responsibility, and alignment with transcendent purpose.

His life becomes a pattern for authentic manhood—purposeful, sacrificial, generative—and a template for building stable families and cultures grounded in the sacred.

Sarah

Sarah, though often overshadowed in traditional readings, is elevated in Peterson’s interpretation as a figure of resilience, transformation, and faith. Initially marked by barrenness, Sarah undergoes a spiritual evolution akin to Abraham’s.

Her renaming from Sarai to Sarah signifies a deepening of identity and vocation. She becomes a mother not just biologically but symbolically—the mother of nations and of the faithful.

Her skepticism about bearing a child in old age reflects the psychological resistance to miraculous change, yet her eventual motherhood demonstrates that even in doubt, the potential for faith can manifest. Sarah also exemplifies the feminine commitment to covenantal life.

She endures uncertainty, displacement, and the complex dynamics of power in patriarchal structures, but her presence affirms the necessity of feminine strength in the divine narrative. Her laughter upon hearing God’s promise, initially cynical, becomes a symbol of the tension between realism and faith—a tension all believers must navigate.

Sarah represents the possibility that even what seems dead—wombs, relationships, faith—can be revived through divine promise and patient obedience.

Jacob

Jacob’s character arc is among the most psychologically rich in We Who Wrestle with God. Initially defined by deceit and manipulation, Jacob embodies the ego-driven self who seeks blessing without moral cost.

His theft of Esau’s birthright and blessing positions him as the archetypal trickster, but his journey does not end in duplicity. Jacob’s transformation begins in exile and culminates in his night-long wrestling with the angel—a literal and symbolic confrontation with the divine, the self, and the moral consequences of his actions.

This struggle, which leaves him wounded, marks the turning point in his life. Renamed Israel, Jacob becomes the one who wrestles with God and prevails—not by domination, but by enduring the struggle with honesty and persistence.

His wound is the mark of growth, the necessary cost of spiritual evolution. Jacob’s story reveals that true maturity arises only after facing the truth of one’s character and enduring the suffering required for rebirth.

He models the human need to confront shadow, accept divine authority, and transform selfish cunning into covenantal integrity. His legacy is not perfection but perseverance, and in this, he becomes a father not just of tribes but of the spiritually awakened.

Moses

Moses in Peterson’s rendering is a profound study in leadership, obedience, and tragic limitation. He is a towering moral figure who speaks with God, liberates his people, and receives the Law, yet he remains a man—a man capable of pride and misstep.

His failure at the waters of Meribah, where he strikes the rock instead of speaking as commanded, is interpreted not just as disobedience but as a subtle act of ego. Moses takes credit for a miracle that should belong to God, signaling the corruption that can creep into even the most faithful lives.

His punishment—being barred from the Promised Land—reveals the sobering truth that no leader is exempt from the demands of humility. Yet Moses is not defined by this failure alone.

He becomes the moral teacher of Israel, delivering the farewell sermon in Deuteronomy with clarity and vision. His character balances justice and mercy, courage and fear, authority and vulnerability.

Moses symbolizes the burden of responsibility, the loneliness of leadership, and the spiritual cost of mediating between God and people. His life ends not in personal triumph but in visionary longing—he sees what he cannot enter, affirming that some rewards are meant not for the self, but for the future shaped by one’s sacrifice.

Jonah

Jonah’s brief but potent narrative is examined as a psychological parable of resistance, suffering, and eventual surrender to divine will. Called to deliver a message of repentance to Nineveh—Israel’s enemy—Jonah flees in fear and defiance.

His descent into the belly of the great fish represents a symbolic death, a period of introspection and symbolic gestation. This crucible becomes a place of transformation, where Jonah, stripped of control and pride, prays with genuine humility.

His eventual compliance saves a city, yet his story does not end with triumph. Jonah’s bitterness at Nineveh’s salvation exposes the limits of human mercy and the difficulty of aligning one’s heart with divine compassion.

He resents grace extended to those he deems unworthy, revealing a still-fractured soul. Jonah stands for the reluctant prophet in all of us—the part that resists sacrifice, avoids moral discomfort, and clings to narrow justice.

Yet his narrative affirms that even flawed vessels can serve divine purposes, and that repentance, even when begrudging, can still open the door to transformation. Jonah’s journey is a call to transcend vengeance, to allow divine mercy to break through human prejudice, and to embrace one’s calling despite fear, resentment, or pride.

Themes

Consciousness as the Divine Capacity for Moral Creation

The narrative begins with the concept of God as an active, dynamic spirit who faces the formless chaos of the cosmos and produces order through speech and intention. This initial act of creation is not merely a cosmological moment, but a foundational metaphor for the human condition.

For Peterson, this portrayal of God is mirrored in human consciousness—the capacity to confront uncertainty and potential and shape it into meaningful reality. Each human being, endowed with the image of God, shares in this capacity to transform the unknown into the known, the chaotic into the structured.

This divine reflection in human consciousness is the cornerstone of our moral responsibility. Consciousness is not neutral or mechanistic; it is moral by nature.

To be conscious is to be aware, and to be aware is to be capable of choosing order over disorder, good over evil. This emphasis on intentional moral action is central to Peterson’s reading of Genesis and serves as a spiritual mandate to live meaningfully and responsibly.

Human Value, Moral Order, and the Image of God

The declaration that human beings are made in the image of God is not merely an ontological claim but a profound statement about human dignity and worth. Peterson draws a direct connection between this biblical idea and the Western foundation of human rights, freedom, and personal responsibility.

The divine image entails more than capacity; it entails duty. If each person carries the divine spark, then each person is not only valuable but accountable.

Moral order emerges not from societal consensus but from this imprinted sacredness. Institutions, laws, and rights must be grounded in this premise or they risk degenerating into mere power structures.

This theme also presents a counter to nihilistic despair or authoritarian imposition. Without the belief in the divine image, societies descend into chaos, treating individuals as expendable or subordinate to collective ideologies.

Conversely, belief in the sanctity of the individual becomes the bulwark against tyranny.

Stewardship and the Misreading of Dominion

Peterson addresses the charge that the Genesis mandate for dominion justifies ecological exploitation. He insists that dominion must be interpreted as stewardship.

The biblical instruction to “dress and keep” the Garden of Eden implies responsibility and care rather than domination and extraction. Misreading dominion as permission to pillage nature is not a flaw in the text but a failure of moral imagination.

True dominion means elevating the good to very good, participating in the divine act of cultivating and preserving the created world. This understanding reframes humanity’s relationship to nature from one of conquest to one of guardianship.

The moral order must extend beyond interpersonal ethics to include environmental ethics, rooted in reverence for creation and alignment with divine intent.

Gender Complementarity and Archetypal Roles

The relationship between Adam and Eve serves as a model of complementary archetypes rather than a hierarchy of power. Adam represents ordered consciousness, the rational mind that names and categorizes.

Eve, emerging from Adam, represents sensitivity to the unknown and the marginal, a receptivity to what lies outside structured order. These roles are mutually necessary.

Without Eve’s orientation to the emergent, Adam’s world risks rigidity. Without Adam’s structure, Eve’s openness risks dissolution.

Their interaction is not one of subordination but dynamic tension. The ideal relationship is not one of dominance but of mutual challenge and growth.

The fall occurs when this balance is disrupted—when pride leads each to overstep their role in the moral cosmos.

The Fall as Archetypal Pride and the Origin of Suffering

The act of eating the forbidden fruit symbolizes an overreach, a rejection of divine boundaries in pursuit of autonomy. Eve’s sin is pride cloaked in compassion—the belief that she can integrate even the serpent, redeem even the poisonous.

Adam’s sin is appeasement, forsaking divine order to maintain favor. This premature grasping at knowledge births self-consciousness, shame, and the awareness of mortality.

The fall is not a punishment but a psychological shift, marking the emergence of neuroticism, performance anxiety, and the temptation to manipulate appearances rather than confront truth. The loss of Eden is the loss of unselfconscious being.

From that moment, suffering is not just external but existential. And yet, suffering is not meaningless; it becomes the pathway to moral development and ultimate redemption.

Moral Transformation through Sacrifice

The stories of Abraham, Sarah, Jacob, and Isaac frame sacrifice as the cornerstone of identity transformation. These figures undergo symbolic deaths and rebirths, shedding immature selves to assume morally grounded identities.

Abraham becomes the father of nations by trusting in something beyond himself and accepting the cost of responsibility. Circumcision becomes both a physical act and a symbolic surrender of excess and ego.

True adulthood is not a function of age but of moral clarity and sacrificial integrity. Sacrifice does not entail arbitrary loss but meaningful transformation—one relinquishes lower aims for higher ones.

This is the spiritual principle echoed in every religious act, every moment of delayed gratification, and every step toward the good.

Hospitality and Cultural Integrity

Abraham’s hospitality contrasts with Sodom’s depravity. Welcoming the stranger is framed as the minimum expression of moral civilization.

Hospitality, in this context, is not about politeness but about the recognition of the other as sacred. The collapse of hospitality is the beginning of cultural collapse.

Sodom’s rejection of the sacred trust between host and guest is not merely immoral but anti-civilizational. Lot’s disturbing offer of his daughters highlights the extremity of that obligation in ancient contexts.

Peterson uses this narrative to critique modern political fragmentation and institutional dysfunction, where distrust replaces dialogue, and communal bonds disintegrate. Cultural survival depends not on ideology but on shared acts of trust and sacrifice.

Confrontation with Chaos and the Necessity of Humility

The serpent in the desert, lifted on a pole, becomes a powerful symbol of redemption through confrontation. Rather than being removed, the threat remains—but the act of looking upon it initiates healing.

This is a spiritual law: one cannot escape suffering or chaos; one must face it consciously. Moses’s error—striking the rock instead of obeying God’s instruction—reveals the danger of pride in leadership.

Even those closest to the divine must remain humble. The ultimate failure is not sin but arrogance—the belief that one can replace divine authority with personal agenda.

In this context, Jonah’s story becomes a psychological journey through resistance, death, and reluctant obedience. His salvation of Nineveh, despite his resentment, shows that moral truth is not contingent on personal comfort.

Redemption through Alignment with the Logos

The flaming sword that guards Eden is both a barrier and a promise. It symbolizes judgment but also the possibility of return.

One cannot go back unchanged. To re-enter Paradise, one must be purified by sacrifice, humility, and truth.

This is not a mystical journey but a moral imperative. Redemption comes not through avoidance or manipulation but through courageous responsibility.

The Logos—the divine principle of truth and order—becomes the only path back. Whether through prayer, thought, or action, the individual must submit to what is higher.

The Genesis narrative ends not in despair but in hope: that through moral struggle and spiritual alignment, one can recover meaning, order, and ultimately, life.