Welcome Home, Stranger Summary, Characters and Themes

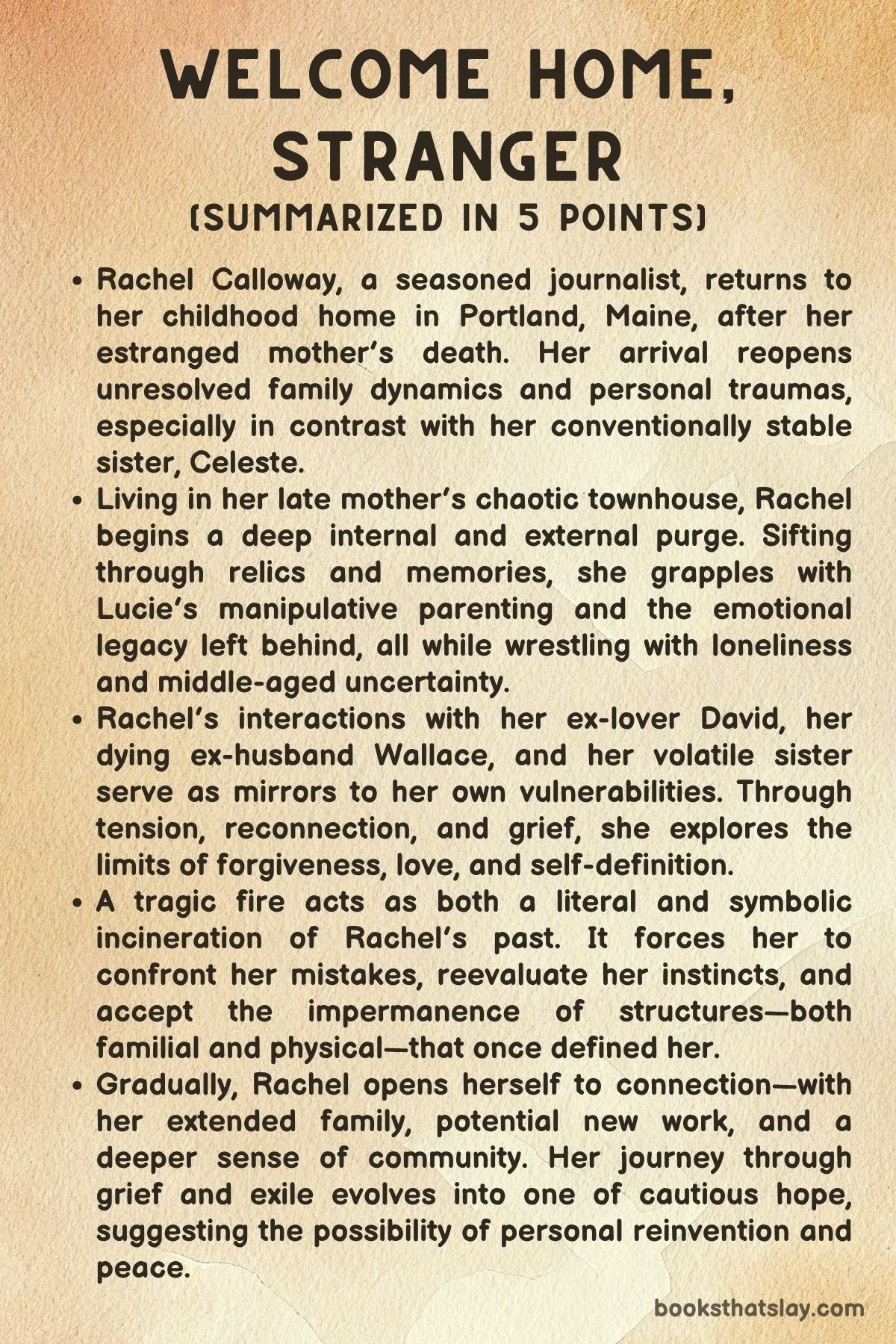

Welcome Home, Stranger by Kate Christensen is a profound literary novel that explores the tangled emotional terrain of grief, family, identity, and self-reclamation.

Set primarily in Portland, Maine, the story follows Rachel Calloway, a middle-aged journalist navigating the aftermath of her estranged mother’s death. Returning to her childhood home unearths not only physical relics but also buried emotions, unresolved familial wounds, and forgotten desires.

Through Rachel’s inward and outward journeys—marked by confrontations with the past, difficult choices, and tentative reconciliations—the novel examines the complex interplay between independence and belonging.

It also explores the resilience required to rebuild from emotional and literal ruin. Christensen’s storytelling is introspective and emotionally intricate, capturing midlife upheaval with compassion and clarity.

Summary

Rachel Calloway returns to her hometown of Portland, Maine, after the death of her mother, Lucie.

Exhausted from months of Arctic reporting and her collapsing personal life, she arrives emotionally unmoored.

Her sister Celeste, firmly rooted in her role as a wealthy wife and mother, picks her up at the airport.

Tensions between the sisters simmer beneath the surface. Rachel feels alienated from Celeste’s domestic world and haunted by unresolved issues with Lucie, a charismatic but emotionally manipulative woman.

Things quickly become more uncomfortable when Rachel learns that her ex-lover, David, now lives next door—married to Celeste’s best friend, Molly.

A strained dinner gathering exposes the emotional rifts within and between families. Rachel tries to engage with her niece and nephew through her work on climate change, but the evening ends in discomfort and sadness.

Her grief is compounded by David’s surprise nighttime visit, which almost leads to intimacy but ultimately results in Rachel pushing him away.

The next morning, Celeste, assuming the worst after her daughter saw David leaving Rachel’s room, throws Rachel out of the house.

Alone and humiliated, Rachel relocates to Lucie’s dilapidated townhouse.

The space is a chaotic time capsule, filled with the remnants of Lucie’s decline. Cleaning becomes both a physical and emotional exercise, as Rachel unearths memories and begins confronting the harsh truths of her childhood—particularly Lucie’s narcissism and neglect.

Conversations with a local realtor and a well-meaning, overly dramatic neighbor reinforce Rachel’s sense of isolation, while also nudging her toward a new kind of autonomy.

In a period of solitude, Rachel reclaims forgotten rituals—grocery shopping, cooking, solitude.

She reflects on her past with Wallace, her ex-husband and closest confidante, who now suffers from ALS.

Their bond, though complicated by his new partner Declan, remains emotionally anchoring. As Rachel further cleans out the townhouse, she reenters her childhood bedroom, confronting ghosts of adolescence and beginning the painful yet necessary process of self-definition.

As she clears out Lucie’s possessions, Rachel contacts Celeste again.

Their conversation about Lucie’s will—Rachel inheriting the house, Celeste the money—brings old resentments into the open.

For the first time, the sisters begin to see their shared wounds and Lucie’s failings with mutual understanding.

Rachel’s attempt to renovate the townhouse ends in disaster when she hires Jesse, a man who reminds her of her cousin Danny.

A fire breaks out, killing Jesse and destroying the house. Devastated, Rachel sees the fire as symbolic of her chaotic attempts at healing.

Looking to reconnect with a part of herself long denied, Rachel arranges a trip with Celeste to the family’s lakeside camp to scatter Lucie’s ashes.

There, she meets extended family members and begins mending long-frayed ties. These encounters ground her in a sense of inherited strength and resilience.

Meanwhile, Wallace’s health deteriorates rapidly. Rachel, devastated by the impending loss, is forced to reckon with her love, guilt, and helplessness.

In the final chapters, Rachel chooses to stay in Portland and pursue a new path.

She finds a room to rent and applies for a nonprofit job. Though grieving and displaced, she begins to see the possibility of building a life rooted not in the past, but in cautious hope.

As she reflects on all she’s lost—her mother, her home, Jesse, and soon Wallace—Rachel makes a choice to continue forward.

Her story closes not with resolution, but with the first fragile steps toward belonging, purpose, and emotional rebirth.

Characters

Rachel Calloway

Rachel is the emotional core of the novel—a middle-aged, sharp-witted journalist wrestling with grief, identity, and long-buried familial trauma. Her journey is marked by a deep introspection catalyzed by the death of her mother, Lucie.

Rachel’s character is defined by contradictions: fiercely independent yet emotionally needy, highly accomplished but riddled with self-doubt, yearning for connection but often sabotaging it. Her estrangement from her sister Celeste and her unfinished business with her ex-lover David reveal layers of guilt, regret, and emotional defensiveness.

Her exile from Celeste’s house pushes her toward painful self-examination. This compels her to confront her mother’s neglect and narcissism.

Through cleaning, scattering ashes, and forging new relationships, Rachel begins to rebuild. Her arc is one of transformation—from bitterness and alienation to hope and self-acceptance.

By the end, Rachel embraces a life in Maine that offers connection and purpose. This signals growth, even without perfect closure.

Celeste Calloway

Celeste, Rachel’s younger sister, represents conventional stability—wealthy, married, and rooted in family structure. Beneath her composed exterior lies moral rigidity, resentment, and emotional control.

Her anger when Rachel is caught with David is about more than betrayal. It’s driven by an ongoing rivalry and her struggle to maintain dominance in a dysfunctional family hierarchy.

Celeste’s efforts to escape Lucie’s chaos result in a life of order that feels like entrapment. She is both the opposite and mirror of Rachel.

Their reconciliation reveals Celeste’s long-buried hurt. It also highlights the different ways they each processed shared trauma.

Ultimately, Celeste’s emotional arc is quieter but profound. She no longer views Rachel as a threat but as a fellow survivor.

Lucie Calloway

Lucie is deceased at the novel’s start, yet her presence permeates every chapter. She is a haunting, contradictory figure—once glamorous and magnetic, later erratic and cruel.

Her parenting was marked by neglect, narcissism, and conditional love. Rachel and Celeste were shaped by her emotional instability.

Lucie is never a flat villain. Through Rachel’s memories and the house she left behind, readers see the tragedy of a woman undone by her own fragility.

Her final gesture—dividing the inheritance unequally—reignites sibling tensions. It also reveals her inconsistent affections.

Lucie becomes a psychological battleground. Through her, both daughters are forced to reassess their identities and futures.

David

David is Rachel’s former lover and now Celeste’s neighbor, married to Molly. Once intense and magnetic, he now appears emotionally diminished.

His reentry into Rachel’s life stirs longing, guilt, and grief. Their near-intimate reunion reopens old wounds and exposes unfinished emotional business.

David functions more as a symbol than a central figure. He represents what Rachel has lost and must leave behind.

His passive acceptance of a life without passion contrasts sharply with Rachel’s yearning for authenticity. He is a cautionary figure reminding her of the costs of emotional inertia.

Wallace

Wallace, Rachel’s ex-husband and closest friend, is a moral anchor in her life. Afflicted with ALS, he is a symbol of both constancy and fragility.

Their bond, though no longer romantic, is deep and irreplaceable. It provides Rachel with a rare experience of unconditional love.

Wallace’s impending death reorients Rachel’s emotional priorities. It forces her to acknowledge her dependence on him.

His decline mirrors the novel’s themes of impermanence and transition. Even as he fades, his presence continues to shape Rachel’s emotional recovery.

Jesse

Jesse is a homeless man Rachel hires to help clean Lucie’s house. His resemblance to Rachel’s late cousin Danny imbues him with emotional resonance.

Jesse is trusting, gentle, and emotionally transparent. Rachel’s decision to bring him into her life is both impulsive and compassionate.

When Jesse dies in the house fire, it devastates Rachel. His death becomes a symbolic turning point—an event that forces her to rebuild from literal ashes.

Jesse is a tragic, redemptive figure. His loss intensifies Rachel’s guilt but also clears the way for her transformation.

Suzanne Brown

Suzanne is an old acquaintance who resurfaces during Rachel’s time in Portland. She is eccentric, wealthy, and philosophically curious.

She offers Rachel practical help in selling the house. But she also challenges her with existential insights about life, pleasure, and mortality.

Suzanne is not central to the family narrative. However, she serves as a reminder that reinvention and indulgence are still possible.

Her confidence and detachment provide Rachel with a needed alternative perspective. Suzanne shows that not all paths to fulfillment must be traditional.

Jenny Baum

Jenny is Lucie’s former neighbor and a self-appointed mourner. She is dramatic, chatty, and insists on inserting herself into Rachel’s grieving process.

Rachel finds Jenny’s behavior performative and invasive. Jenny represents the kind of social grief Rachel rejects.

Still, Jenny reflects the community’s memory and shared history. Her presence contrasts Rachel’s emotional isolation.

Jenny reinforces one of the book’s key tensions. Grief can be communal, but it often feels deeply personal and incommunicable.

Themes

Grief and the Aftermath of Loss

Grief in Welcome Home, Stranger is not a single event but a pervasive emotional condition that saturates every corner of Rachel Calloway’s return to Portland. The death of her mother Lucie triggers a cascade of psychological reckonings, not just with Lucie’s physical absence but with her lingering emotional power.

Lucie’s death acts as both an ending and a cruel opening, revealing the unfinished emotional business Rachel must face. Throughout the novel, Rachel’s process of mourning becomes intensely personal, shaped as much by anger and guilt as by sorrow.

She confronts a mother who was deeply flawed—manipulative, self-absorbed, and emotionally neglectful. Her grief, therefore, lacks the purity or catharsis usually associated with loss.

Instead, it is fragmented, ambivalent, and delayed, manifesting through arguments, insomnia, hallucinations, and compulsive cleaning. Rachel is not mourning an idealized figure but wrestling with the ghost of a relationship that never quite healed.

The rituals associated with death—cleaning out the house, scattering ashes—become moments of forced intimacy with a woman who was distant even in life. Furthermore, Rachel’s grief is compounded by the anticipatory mourning of Wallace, her ex-husband who is dying of ALS.

His slow decline adds another layer to her sorrow, deepening her contemplation of mortality, love, and the passage of time. Rather than seeking closure, Rachel begins to understand that grief is not something to overcome but something to live with.

It becomes an emotional state that reshapes identity, memory, and one’s place in the world. The novel uses grief as a force that strips Rachel bare, so she can begin the painful but honest work of becoming someone new.

Estrangement and the Fracture of Family Bonds

The theme of estrangement threads through Rachel’s interactions with nearly every member of her family, particularly her sister Celeste. From the outset, the contrast between the two sisters is stark—Celeste’s rooted domestic life clashes with Rachel’s nomadic, career-driven detachment.

Their relationship is marked by jealousy, resentment, and mutual misunderstanding. Rachel sees Celeste as smug and judgmental, while Celeste views Rachel as irresponsible and morally dubious, especially after the David incident.

This rift becomes a symbolic manifestation of deeper familial fractures, reflecting how each daughter absorbed and reacted to their upbringing in different ways. Their estrangement is not just personal but philosophical—about what constitutes a meaningful life, how love is expressed, and what loyalty looks like.

Even their inheritance from Lucie serves as a battleground, dividing them emotionally and practically. Yet estrangement is not limited to the sisters.

Rachel also feels alienated from her community, her mother’s memory, and even herself. For much of the novel, she navigates the world like an emotional outsider, burdened by a childhood that taught her to distrust intimacy and emotional transparency.

The presence of extended family in the final part of the novel offers a tentative path toward reconnection, but it is cautious and incomplete. The story suggests that familial estrangement is not something easily resolved through shared blood or forced rituals.

It requires emotional honesty, painful confrontation, and often a willingness to rebuild relationships from scratch. Rachel’s journey shows how difficult that process is, especially when trust has long since eroded.

Female Identity and Midlife Crisis

Rachel’s midlife serves as the crucible for many of the novel’s tensions. The exploration of female identity at this life stage is one of the book’s most profound themes.

At fifty-two, Rachel is neither youthful nor elderly, but caught in a liminal space where the societal scaffolding for self-worth—beauty, motherhood, marital status—has eroded. She has no children, is long divorced, and is now grieving the man who came closest to being her lifelong partner.

Her career, once her stabilizing force, now feels tenuous. This crisis of identity is both internal and external, rooted in the invisible toll of aging in a society that prizes youth and domestic stability for women.

Christensen portrays this not as a tragedy, but as a reckoning. Rachel is forced to reconsider who she is when stripped of the roles that once defined her.

Her relationship with Celeste exacerbates this reckoning, as she is constantly reminded of the societal rewards her sister has accumulated through marriage and motherhood. However, the novel refuses to idealize either path.

Celeste’s life is revealed to be brittle and performative, haunted by its own discontent. Through this comparative lens, Rachel begins to reject binary choices.

She explores solitude not as loneliness but as a space for reinvention. She learns that identity at midlife is not about recapturing youth or conforming to expectation, but about constructing meaning from what remains.

Her choices—clearing out Lucie’s house, contemplating a new job, swimming again—reflect this desire to become, rather than simply to be. Female identity, as portrayed here, is not a fixed role but a continuous act of self-definition.

The Burden and Ambiguity of Legacy

Legacy in Welcome Home, Stranger is depicted as both material and emotional. In both cases, it is fraught with contradiction.

Rachel inherits her mother’s house, a decaying space full of clutter, secrets, and painful memories. This inheritance is not a gift but a burden, representing the weight of Lucie’s dysfunction and unresolved maternal damage.

The physical act of sorting through her mother’s belongings becomes a symbolic journey into the moral and emotional legacy she has been left. Each item Rachel discards or keeps tells a story—not just about Lucie, but about how Rachel has come to understand love, neglect, memory, and worth.

The will, which divides money and property between the sisters, becomes a lightning rod for long-brewing tensions. Yet beyond possessions, legacy manifests in subtler ways.

Rachel’s estrangement from family, her emotional volatility, and her deep distrust of intimacy all stem from Lucie’s manipulative parenting. Lucie’s legacy is one of fragmentation, but it also contains paradoxes.

Rachel, despite her mother’s failings, carries forward traits of resilience, independence, and fierce intellect that can be traced to Lucie’s more admirable sides. This duality challenges Rachel’s understanding of inheritance—not just what is passed down, but what is absorbed, resisted, or reshaped.

The final act of scattering Lucie’s ashes is not a moment of resolution but of symbolic reckoning. It’s an acknowledgment that legacy, especially maternal legacy, is never clean.

It is messy, incomplete, and often carries emotional toxins that must be consciously processed, lest they metastasize across generations.

Reconnection and the Longing for Community

Despite Rachel’s self-professed independence, the novel quietly reveals a deep longing for connection and community that she has suppressed for much of her adult life. At first, she wears her isolation like armor—justified by her career, her politics, and her intellectualism.

However, this independence gradually reveals itself to be both a strength and a wound. Her discomfort at Celeste’s family gatherings, her awkwardness around neighbors, and her skepticism toward new acquaintances like Jenny Baum all signal a woman who has forgotten how to be part of a social fabric.

The destruction of Lucie’s house, her loss of a home, and Wallace’s impending death all strip Rachel of the last vestiges of her old life. These losses make the need for community impossible to ignore.

Her journey to the lakeside camp becomes a turning point—not in the form of a grand reconciliation, but in a quiet realization that she was denied access to her wider family through Lucie’s isolationism. When Rachel begins to reconnect with cousins and consider a local job, the narrative suggests that healing may lie in reintegration.

Allowing oneself to belong again is portrayed as essential. This yearning does not imply dependence, but an acknowledgment that being part of a collective—family, neighborhood, professional circle—can provide scaffolding for rebuilding one’s life.

Community is not idealized, but shown as a structure that supports growth and accountability. Rachel’s decision to stay in Maine, join a book club, and consider a job offer is not just about logistics.

It is an emotional commitment to reenter the human circle from which she has long been estranged. That reentry marks the beginning of a new emotional life rooted not in self-protection, but in interdependence.