What It’s Like in Words Summary, Characters and Themes

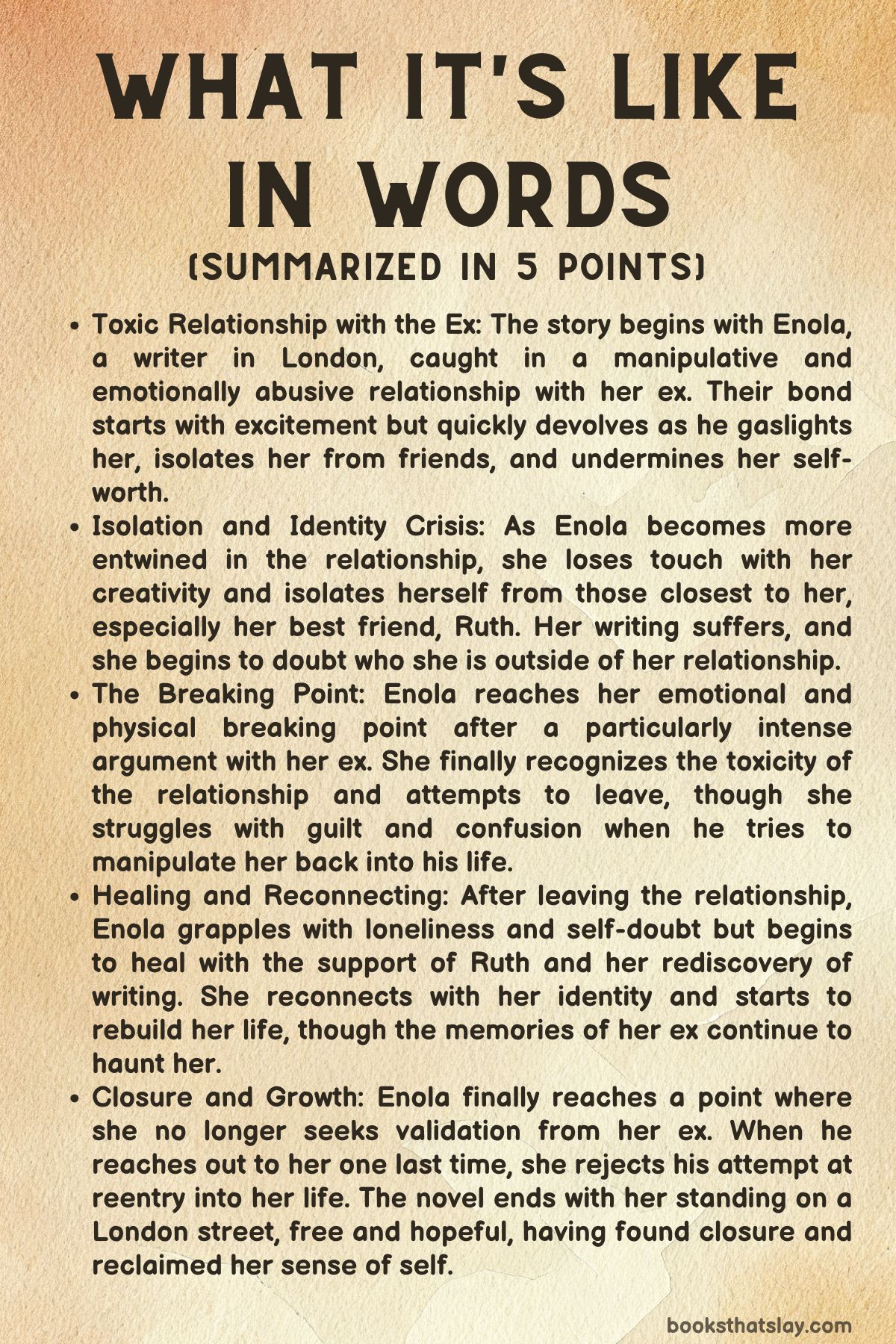

What It’s Like in Words by Eliza Moss is a psychologically layered novel that follows a young woman named Enola as she navigates a toxic romantic relationship, creative stagnation, personal trauma, and the long, jagged road toward reclaiming her sense of self. The book is written in a voice that blurs present experience with memory and emotional impression, offering an unflinching portrayal of the slow erosion of identity in the face of psychological manipulation.

With striking internal detail and careful attention to emotional nuance, the story charts how desire, grief, and the need to be seen can distort love and make cruelty feel like intimacy. Moss captures the complex interiority of a woman trying to write herself back into existence.

Summary

Enola is a young writer in her twenties experiencing a period of creative and emotional inertia when she meets a man at her writers’ group who immediately unsettles her. His arrival is brash and disruptive; he upends the group’s dynamic with a blunt insult and soon draws Enola’s fascination.

What starts as romantic intrigue quickly spirals into a pattern of psychological entanglement. Their early interactions are a mix of flirtation and emotional power-play—conversations laced with intellectual sparring, subtle undermining, and erotic tension.

Enola feels simultaneously destabilized and alive, sensing that this relationship might redefine her identity. However, this very intensity becomes the seed of self-erasure.

Initially, Enola adjusts her habits, personality, and self-expression to suit his moods. She grows more uncertain, second-guessing what she wears, says, or likes, worried about how he will interpret it.

His humor, once alluring, turns into a vehicle for quiet cruelty. Their sexual relationship is marked by moments Enola later questions—she often rewrites uncomfortable experiences as consensual to avoid confronting the lack of emotional safety.

Her best friend Ruth becomes increasingly concerned, noticing how Enola’s spark has dimmed and her independence is shrinking. Ruth tries to intervene, but Enola remains enchanted by the fantasy of romantic transformation.

The relationship intensifies during a trip to Kenya, Enola’s childhood home. The setting serves as an emotional crucible—filled with memories, unresolved trauma, and a haunting sense of disconnection.

Her partner becomes increasingly distant and irritable, uninterested in the cultural or emotional resonance the country holds for her. When she arranges to visit her estranged aunt, he refuses to join and later mocks her for being affected.

The heat, illness, and physical discomfort she experiences mirror her psychological exhaustion. Though she continues to perform affection and desire, the emotional intimacy has frayed.

Their sex becomes rote, and her need for reassurance is met with irritation or detachment.

By the time they return, Enola begins to see cracks in the relationship she once idealized. She tries to salvage their connection with grand gestures—planning surprises, making a handmade card—but the response is cold or condescending.

When she discovers him out with another woman and eventually receives a breakup that frames itself as an act of emotional maturity, she is left humiliated and hollow. Even then, she struggles to let go, clinging to the fantasy that he might still love her or that she failed to be enough.

In the aftermath, Enola attempts to reclaim her independence with nights out, bold haircuts, and affirmations of singlehood. But these efforts collapse into self-loathing and emotional desperation.

She contacts him again, leading to a one-sided, emotionally harmful sexual encounter where her longing for connection is ignored. He reasserts control, making clear that it was a one-time event.

As he returns to his writing, she is again discarded. But this marks a quiet turning point.

With Ruth’s steady encouragement, Enola returns to her manuscript, finishes it, and submits it to an agent.

The process of writing revives something in Enola. Her creativity, once flattened by his constant criticism, becomes a source of power.

A positive response from the agent brings her a rush of validation that is self-generated, not extracted from a man. At the same time, she reflects on her childhood, her father’s death, and her complex grief.

The holidays bring both warmth and emotional reckoning, especially when a photograph of her father triggers deeper memories and feelings long buried.

When her ex reappears, texting her and suggesting a meeting, Enola agrees with caution. They meet in a graveyard, an emotionally charged setting that underscores the dead weight of their former connection.

Though there is still chemistry, it’s more familiar than real. They share a kiss, but it lacks the illusion of transformation that once bound her to him.

This time, she sees more clearly. A brief reconciliation follows, but on her birthday, his distance resurfaces.

She finally confronts the fact that she no longer wants to mold herself to someone else’s needs. With Ruth’s consistent support and the memory of her father’s emotional honesty guiding her, she chooses to reject both him and the illusion of love she once constructed.

Her turning point is not only romantic but existential. She reconsiders another relationship with Virinder, a man she dated briefly and who seemed safe but uninspiring.

Though he represents an alternative to her toxic ex, Enola realizes that choosing someone solely because they are different is not the same as choosing someone because they are right for her. In refusing both extremes—the magnetic but harmful ex and the too-easy replacement—she begins to center herself.

The emotional climax occurs during a confrontation with her estranged mother. Enola demands answers about her father’s death and her own childhood, pressing through years of silence and avoidance.

The conversation brings painful clarity: her father was not the perfect figure she imagined, and her mother’s emotional distance has shaped her capacity for attachment. These realizations destabilize her but also liberate her.

She can finally start to understand the roots of her longing and begin the process of self-definition.

After a near-violent emotional spiral—including a shocking moment in which Enola pushes her ex onto train tracks—the story shifts to recovery. She flees the scene, numbed by guilt and confusion, unsure whether she will be caught or whether she wants to be.

The aftermath is muted by fear and reflection. When Ruth returns and the two reconcile, Enola begins to speak honestly, though she does not reveal everything.

Then comes a moment of renewal: her book is going to be published. For the first time, her identity as a writer is validated on her own terms.

The novel closes with Enola refusing to accept apologies or crumbs of affection from her ex. She chooses distance, clarity, and her own voice.

With Ruth beside her and the promise of a future shaped by her own choices, she steps into a new life—not fully healed, but fully present. What It’s Like in Words ends not with triumphant closure but with the quiet, powerful act of beginning again.

Characters

Enola

Enola is the central figure in What Its Like in Words, and the novel is essentially a vivid excavation of her internal world. A young writer in her twenties, she begins the story caught between emotional disarray and creative stagnation, embodying the confusion and fragility of someone searching for meaning, identity, and love in a world that constantly undermines her sense of self.

Her journey is portrayed with heartbreaking clarity—from her magnetic attraction to a dangerous man to her eventual realization that her desire to be seen and validated has led her into emotional entrapment. Enola is not naïve, but she is susceptible, caught in the paradox of knowing better while still hoping for the worst to transform into something good.

Her romantic obsession drives her to reshape her personality around her partner’s preferences, sacrificing autonomy for affection. What makes Enola so compelling is her intense interiority; she is deeply self-aware, even as she falls into patterns of self-erasure.

She is haunted not just by this toxic relationship but also by unresolved grief from her father’s death and a lifelong sense of disconnection from her emotionally distant mother. Her eventual arc toward empowerment is not linear but raw and honest.

She breaks, she doubts, she lashes out—most notably in the shocking moment of pushing her partner onto the tracks—but this rupture becomes a threshold. Ultimately, Enola becomes a symbol of a woman reclaiming narrative control, choosing herself and her voice over validation from men who fail to truly see her.

Ruth

Ruth is Enola’s best friend and moral compass throughout What Its Like in Words. She provides emotional ballast in a narrative that is otherwise defined by psychological turbulence.

Ruth is fiercely protective, unafraid to confront Enola with uncomfortable truths about her partner’s manipulation and gaslighting. Her unwavering support is both comforting and challenging—Ruth doesn’t coddle Enola, but instead demands that she recognize her own worth and agency.

She plays the role of the loyal friend who has endured the emotional fallout of watching someone they love spiral into self-destruction. Ruth is the voice of reason, the one who calls out the toxicity Enola is too enmeshed to name.

However, their relationship is not without tension. Ruth’s honesty often leads to conflict, and her frustration with Enola’s repeated return to the emotionally abusive relationship creates moments of estrangement.

These tensions reflect the difficulty of loving someone who is hurting but not yet ready to heal. Yet Ruth never walks away.

Her presence at the end of the novel, after Enola’s moment of reckoning, reinforces the novel’s emphasis on female friendship as a site of healing and resilience. Ruth does not rescue Enola, but she stands beside her as Enola rescues herself, offering unconditional care without trying to rewrite her pain.

Enola’s Partner (The Man)

The unnamed partner in What Its Like in Words is a deeply manipulative and emotionally abusive figure. He begins as an enigmatic, electrifying presence—intelligent, confident, sharply witty—and it’s this combination that initially draws Enola in.

His charisma masks a darker core, one rooted in insecurity, narcissism, and an insidious need for control. Through subtle put-downs, backhanded compliments, and gaslighting, he erodes Enola’s sense of self while cloaking his cruelty in sophistication.

He often presents as the misunderstood genius, someone burdened by his own brilliance, thereby justifying his emotional distance and lack of accountability. His emotional unavailability, initially perceived as depth or mystery, reveals itself as a weapon.

He invalidates Enola’s feelings, mocks her insecurities, and constantly shifts blame to maintain dominance in their relationship. Even moments of apparent intimacy are transactional or performative—his affection extends only so far as it serves his ego.

His lack of empathy during their trip to Kenya, especially in response to Enola’s emotional and physical distress, illustrates his complete detachment from genuine connection. The most chilling aspect of his character is how convincingly he frames Enola’s growing despair as her own flaw, convincing her that she is too needy, too sensitive, or not strong enough.

Even when he returns after the breakup, his apologies are hollow, devoid of recognition for the harm he caused. He is a haunting representation of how charm and intellect can be weaponized in emotionally abusive dynamics.

Virinder

Virinder occupies a complicated space in Enola’s emotional landscape in What Its Like in Words. Initially introduced as a rebound, he quickly becomes a foil to Enola’s ex.

On the surface, he represents stability and artistic camaraderie—another writer, sensitive and available. However, beneath this polished exterior lies a subtler but no less damaging strain of emotional manipulation.

He uses Enola’s trauma and affection as tools for control, often turning her vulnerability into an inconvenience or an excuse to assert his superiority. Virinder’s toxicity is not explosive but corrosive, a slow chipping away at Enola’s confidence.

He often centers himself in conversations meant to be about her pain, and when she seeks support, he offers detachment instead. His dismissiveness after Enola’s traumatic encounter at the train station is especially cruel, revealing his complete unwillingness to engage emotionally unless it benefits him.

Despite his apparent “niceness,” Virinder’s true nature emerges in how he subtly reinforces Enola’s dependency—one that thrives on her self-doubt. He denies meaningful attachment, reduces their intimacy to casual flings, and frames her reactions as overblown or irrational.

His presence in the novel complicates the dichotomy between the obviously abusive and the seemingly safe, reminding the reader that emotional abuse can wear many masks, including that of the “nice guy. ” Enola’s final rejection of him signifies a vital step in her journey toward self-determination.

Enola’s Mother

Though a relatively peripheral character in terms of physical presence, Enola’s mother casts a long psychological shadow in What Its Like in Words. Her emotional absence during Enola’s upbringing plays a critical role in shaping the protagonist’s yearning for affection and approval.

The mother-daughter relationship is steeped in silence, denial, and unspoken grief—particularly around the death of Enola’s father. When they finally reconnect, the confrontation is both explosive and cathartic.

Enola seeks answers and accountability, while her mother initially deflects, clinging to her own version of events. However, their conversation reveals that her mother, too, is a product of emotional suppression and generational trauma.

She confesses to her failings, to the complexities of their shared past, and to the truth about Enola’s father, shattering the idealized image Enola had clung to for years. This reckoning is pivotal—it not only forces Enola to reframe her childhood narrative but also allows her to locate the roots of her emotional patterns.

The mother is not redeemed, but she is humanized, and her reluctant honesty opens a new space for healing. Her role in the story emphasizes how family legacies of silence and emotional repression can distort self-perception and feed cycles of dependency and pain.

In confronting her mother, Enola begins the slow and painful work of untangling herself from inherited wounds.

Enola’s Father

Though deceased, Enola’s father remains a haunting presence throughout What Its Like in Words. His death and the mystery surrounding it act as a psychological undertow in Enola’s life, shaping her grief, identity, and longing for stability.

Early in the narrative, he is idealized—an anchor of love and consistency in contrast to her emotionally distant mother and chaotic present. However, as repressed memories resurface, this idealization is called into question.

Enola begins to remember moments that complicate her image of him, suggesting he may not have been the nurturing, benevolent figure she imagined. This process of recollection and reevaluation is devastating but necessary.

It mirrors Enola’s broader journey of dismantling illusions—whether about men, family, or herself. Her father represents both a source of comfort and a symbol of emotional denial, a figure onto whom she projected her longing for unconditional love.

The revelation of his complexities does not erase her affection, but it liberates her from the burden of mythologizing him. Accepting the full truth of who he was becomes an essential act of emotional maturity for Enola, allowing her to grieve authentically and move forward with a more grounded sense of self.

Themes

Emotional Abuse and Psychological Manipulation

In What It’s Like in Words, the toxic dynamics of emotional abuse unfold gradually but unmistakably. The abuse is not overt in the form of physical violence or clear-cut threats, but it thrives in psychological spaces—through ridicule masked as wit, domination cloaked in charm, and intimacy that serves as a gateway to control.

Enola’s partner repeatedly destabilizes her confidence by criticizing her creativity, undermining her taste, and subtly shifting the blame onto her in every confrontation. His expressions of affection are often coupled with passive-aggressive barbs that disorient Enola and compel her to second-guess her instincts.

He exploits Enola’s emotional vulnerability, especially her craving for validation, and uses it to reinforce her dependency on him. When she seeks emotional closeness, he deflects or reacts with coldness, often manipulating her into feeling guilty for having needs at all.

Gaslighting becomes a regular tactic, blurring Enola’s perception of reality and prompting her to question her recollection of events, her feelings, and even her moral compass. The emotional abuse escalates until Enola becomes a fragment of who she was—trying harder, dressing differently, apologizing more, yet never earning the affection or stability she hopes for.

Her inability to identify the abuse in real time, especially as it is veiled in intellectual and romantic pretensions, captures the insidious nature of psychological manipulation. The book underscores how emotional abuse thrives not through brute force but through the erosion of self-trust and the redefinition of love as something that must be earned through sacrifice.

Identity Erosion and Self-Loss

The narrative powerfully tracks the systematic erosion of Enola’s identity over the course of her relationship. At the outset, she is presented as someone with clear preferences, routines, and personal boundaries, albeit guarded and cautious.

However, as her involvement deepens, her sense of self becomes increasingly distorted. The process is subtle—changing how she dresses, reshaping her opinions to align with his, rethinking her writing voice, and abandoning previously held convictions.

Every small compromise chips away at her autonomy, and she begins to curate her personality to become more desirable in his eyes. The relationship’s imbalance forces her to internalize the idea that her true self isn’t lovable enough, that she must shrink or morph in order to deserve his attention.

Even her memories become unreliable, as she rewrites painful sexual encounters to make them appear consensual or even pleasurable. This need to reframe reality is a defense mechanism—a way to hold onto dignity in a situation that gradually strips her of it.

By the time she reaches the point of crisis, Enola is no longer sure who she is or what she believes. Her tastes, her relationships, and even her core values have been filtered through the lens of someone else’s judgment.

Her journey, then, is not just about leaving an abusive partner but about recovering the parts of herself that were buried beneath the need to be seen and loved by him. The novel meticulously explores how the dismantling of self can occur not all at once, but inch by inch, beneath the guise of romance.

Grief, Memory, and Parental Legacy

Grief in What It’s Like in Words is never isolated—it bleeds into relationships, distorts memory, and influences how Enola perceives herself and others. The loss of her father casts a long shadow over her emotional world.

He is both idolized and obscured, his memory treated as a sacred artifact around which Enola builds her identity. However, as the narrative unfolds, the idealized version of him begins to crumble.

Conversations with her estranged mother and recovered memories challenge her earlier beliefs, introducing complexity and ambiguity into what was once a clear-cut narrative of loss. This revised understanding of her father parallels Enola’s shifting perspective on her romantic relationship; in both cases, she is forced to confront how desperately she wanted to believe in the goodness of men who, in different ways, failed her.

Her unresolved grief becomes a wound that manipulative men can exploit, and her desire for emotional closeness becomes entangled with a need for paternal replacement. The story also investigates how familial silences—secrets, omissions, emotional coldness—perpetuate patterns of self-doubt and emotional suppression.

Enola’s mother is not merely distant but actively evasive, forcing Enola to seek clarity and truth on her own terms. The book portrays grief not as a single moment of mourning but as a lifelong negotiation with memory, identity, and inherited silence.

Ultimately, reclaiming her father’s story is not about affirming a fantasy but about making peace with complexity, which becomes a crucial step toward personal healing and emotional maturity.

Feminine Rage and Moral Ambiguity

The climactic scene in which Enola pushes Virinder onto the train tracks is a stunning rupture that reframes the entire narrative. This act, born from accumulated trauma, despair, and humiliation, embodies a moment of unfiltered feminine rage.

It is not easily categorized as righteous or criminal—it is a transgression that exists in a moral grey area, forcing the reader to grapple with the psychological buildup that leads to such violence. Throughout the novel, Enola has been conditioned to suppress anger, to reframe mistreatment as miscommunication, and to swallow indignity with grace.

Her murder of Virinder does not read as an act of premeditated revenge but as an instinctual release from years of psychological entrapment. The ambiguity surrounding this act—her immediate guilt, her silence, her frantic desire for Ruth’s support—reinforces how rage in women is often pathologized rather than understood.

The book refuses to render judgment, instead exploring the psychic cost of being repeatedly invalidated, manipulated, and unseen. Enola’s rage is not presented as noble or empowering in a simplistic sense.

It’s messy, terrifying, and raw. This act, and her subsequent emotional fallout, serve as a critique of how women’s pain is often dismissed until it erupts in irreversible ways.

In its refusal to sanitize or condemn her actions, the book makes space for moral discomfort. It asks whether survival sometimes comes at the cost of morality, and whether reclamation of agency can ever be entirely clean.

This theme adds layers of psychological realism, compelling the reader to contend with the limits of endurance and the complexity of human response to prolonged abuse.

Female Friendship and Emotional Sanctuary

In contrast to the toxic romance at the heart of the story, the relationship between Enola and Ruth offers a stabilizing counterweight. Ruth functions as Enola’s emotional anchor, her mirror, and occasionally her moral compass.

Their friendship is not idealized; it undergoes strain, conflict, and miscommunication, especially when Ruth confronts Enola about her toxic relationships and long-buried traumas. Yet it is also the space where Enola is most authentically herself.

Ruth’s unwavering presence throughout the highs and devastating lows of Enola’s journey highlights the enduring strength of female friendship as a site of healing and truth. Where romantic love demands that Enola change, Ruth’s love demands only honesty.

She challenges Enola without manipulating her, supports her without enabling self-destruction, and holds space for her even when boundaries are tested. The book foregrounds how genuine friendship can offer a template for emotional intimacy that is not rooted in dominance or neediness but in reciprocity and care.

Ruth becomes the person Enola returns to after every fall, and their reconciliation near the end of the book is portrayed not just as forgiveness but as survival. It is through Ruth’s emotional labor that Enola finds the courage to confront her past, to make sense of her grief, and to begin imagining a future beyond the abusive cycles that defined her adult life.

The friendship is not merely a subplot—it is the emotional core of the novel. In a world where love is often conflated with possession or control, Ruth represents love that liberates.

Their bond illustrates the power of being truly seen and accepted, even in the midst of chaos.