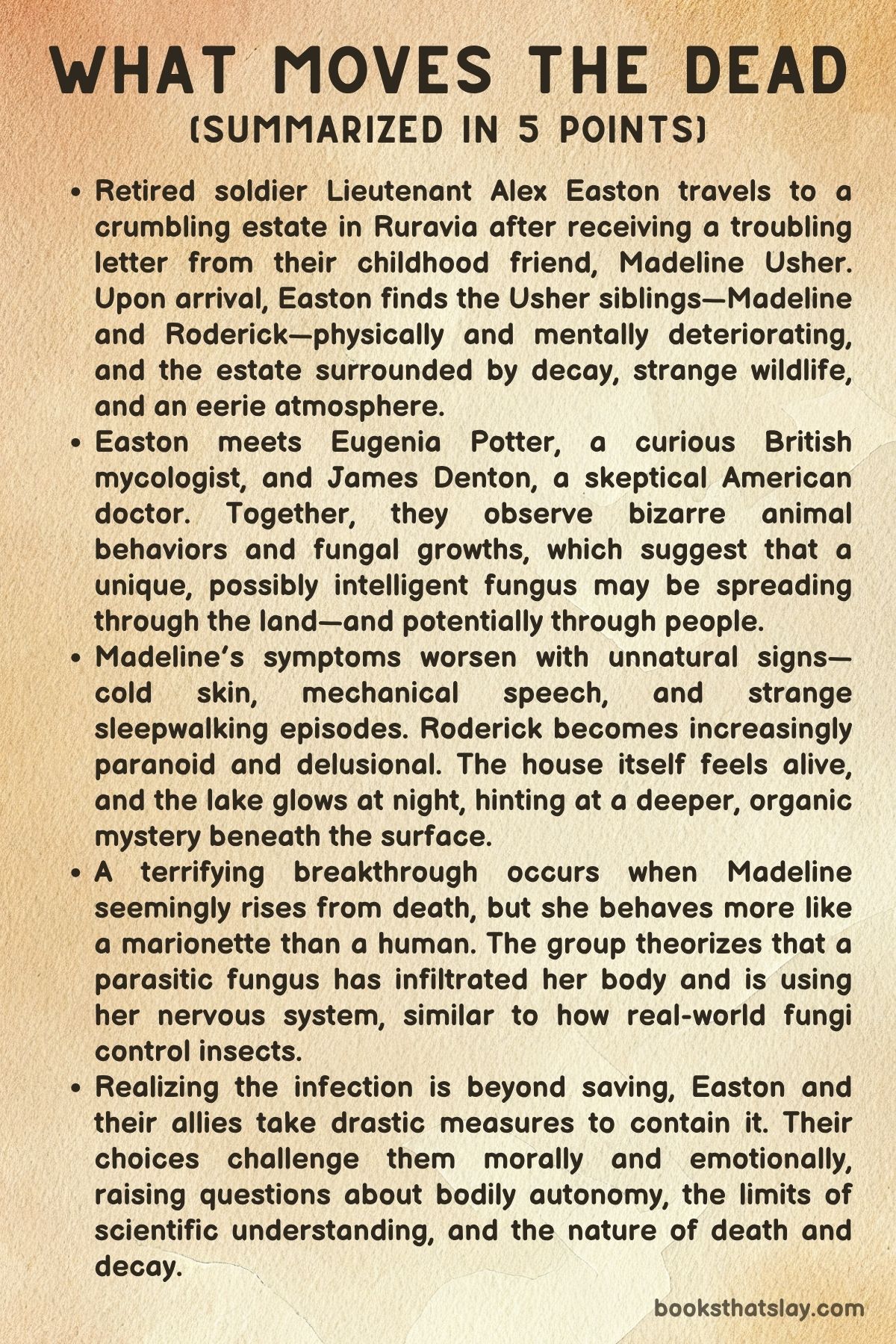

What Moves the Dead Summary, Characters and Themes

What Moves the Dead by T. Kingfisher is a gothic horror novella inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher.

Set in a decaying manor in a remote corner of Ruravia, it follows former soldier Alex Easton as they respond to a troubling letter from a childhood friend. Upon arrival, Easton finds the Usher twins in states of disturbing decline, the estate plagued by unnatural phenomena, and the environment teeming with bizarre fungal growth. This unnerving story blends body horror, psychological suspense, and speculative science to explore the fine line between life and death, sanity and madness.

Summary

Lieutenant Alex Easton arrives at the crumbling Usher estate in Ruravia after receiving a letter from Madeline Usher, an old friend who hints at a grave illness.

The mansion is in a grim state of disrepair, and its surroundings are cloaked in unnatural silence.

Easton finds Madeline looking deathly pale and eerily lifeless, while her brother Roderick seems mentally deteriorated and paranoid, hearing noises in the walls.

A sense of rot and sickness clings to the place.

Easton is joined by Eugenia Potter, an eccentric British mycologist studying the odd fungi growing on and around the estate.

They are also joined by James Denton, an American doctor and fellow war veteran.

Denton has been treating Madeline, though with little success.

He suspects she is experiencing cataleptic episodes that mimic death.

Despite her fragile condition, Madeline insists she feels stronger and speaks cryptically about the lake and confessing sins.

Easton’s loyal servant Angus arrives and immediately senses something is wrong.

He echoes local legends about “witch-hares” and other eerie folk beliefs.

Easton is skeptical but starts noticing oddities—hares dragging themselves unnaturally, staring without blinking.

Potter explains she’s encountered strange aquatic fungi in the region, but even she is unsettled by what she’s seen.

Nightmares begin to plague both Denton and Easton.

Madeline’s behavior grows stranger.

She is found sleepwalking in a rigid state, her limbs light and cold, her smile unnerving.

Potter and Denton suspect that the fungi might not just be surrounding them—it could be infecting the Ushers themselves.

To improve the household’s nourishment without damaging Roderick’s pride, Easton and Angus stage a hunting accident to obtain a cow.

They butcher it and supply the kitchen with fresh meat.

Even this brief episode of levity is shadowed by the disturbing behavior of local wildlife and the growing belief that something deeper is wrong.

Fish from the nearby lake are discovered with slime and fibrous growths.

The lake itself glows at night with unnatural phosphorescence.

Madeline’s symptoms worsen—her skin becomes translucent, her speech robotic.

She begins using words incorrectly and counting her breaths, suggesting the erosion of her identity.

Roderick, too, is falling apart mentally, and Easton suspects both twins may be infected.

Eventually, Madeline collapses entirely, appearing dead.

Denton, however, warns that she should not be buried.

He now believes a parasitic fungus is animating her body from within, hijacking her nervous system.

Exploring the estate, the group discovers massive fungal growths inside the walls and floorboards.

Spores permeate every damp crevice.

The house is being consumed from the inside.

In a horrifying climax, Madeline rises again, her movements puppet-like and her voice mechanical.

She is no longer human, only a vessel.

Potter confirms the fungus has mastered her motor control.

Roderick confesses his dread and accepts his fate, revealing that he, too, has been hearing the voice of the infection.

The group concludes that the fungus cannot be allowed to spread.

Easton decides to burn down the house, and together with the others, sets it ablaze using kerosene.

As flames engulf the building, fungal masses react violently, releasing spores and smoke.

Madeline is destroyed, and Roderick chooses to remain behind, consumed by both guilt and infection.

In the aftermath, Easton reflects on the horrors they have witnessed.

Though the house is gone and the worst appears contained, an unease remains.

Denton and Potter plan to publish their findings discreetly.

Easton rides away, haunted by what they now know.

The dead do not always rest, and sometimes, what moves them is something ancient, biological, and terribly real.

Characters

Alex Easton

Alex Easton serves as the protagonist and narrator, bringing a unique voice grounded in their background as a Gallacian retired soldier. Easton’s narrative is shaped by a blend of military pragmatism and deep emotional connection to the Usher twins, especially Madeline.

As they navigate the decaying estate and the growing terror, Easton emerges as both rational and emotionally responsive. They approach the eerie phenomena with skepticism but remain open to alternative explanations, reflecting a flexible and empathetic mindset.

Their military past informs their resilience and problem-solving, particularly when faced with the decision to burn down the Usher estate. This act cements Easton’s transformation from an observer into a decisive actor, willing to make harrowing sacrifices for the greater good.

Madeline Usher

Madeline is the central figure of mystery and horror, around whom the plot’s tension revolves. Initially frail and spectral, her condition rapidly deteriorates into something inhuman, revealing the novel’s chilling core.

Despite being nearly catatonic, Madeline occasionally exhibits lucid speech and unsettling awareness, which heightens the uncanny atmosphere. Her physical transformation—from pallid weakness to fungal puppet—symbolizes the novel’s themes of bodily autonomy, decay, and the grotesque.

Through Madeline, T. Kingfisher explores the horror of parasitism and identity loss. Though she appears increasingly distant from her humanity, Madeline’s tragedy lies in the brief flickers of awareness that suggest her consciousness may still reside within the infected shell.

Roderick Usher

Roderick is a figure consumed by dread, paranoia, and guilt. His decline mirrors Madeline’s but takes a more psychological route at first.

From the outset, Roderick exhibits auditory hallucinations and an obsessive fear of the house, hinting at a deeper awareness of the unnatural forces at play. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that he, too, may be infected, his gradual loss of self culminating in his quiet decision to remain in the burning house.

His arc is one of passive surrender, contrasting sharply with Easton’s active resistance. Roderick’s tragedy is in his helplessness—he recognizes the horror but is powerless to escape it, ultimately choosing death over further loss of identity.

Eugenia Potter

Eugenia Potter is a critical figure of reason and scientific inquiry in the story. A British mycologist, she brings a grounded, methodical approach to the bizarre events surrounding the Usher estate.

Her interest in fungi starts as a professional curiosity but evolves into an urgent investigation as the biological horror unfolds. Potter represents the tension between science and the supernatural; while she offers plausible theories about fungal parasitism, even she is unsettled by the implications.

Her work provides crucial insight into the infestation, and her partnership with Denton and Easton helps form the intellectual resistance against the spreading horror. Through her, the novel situates fungal terror within the realm of emergent biological science, rather than pure fantasy.

James Denton

James Denton is an American doctor and war veteran who complements Easton’s military pragmatism with medical skepticism and moral reflection. Initially frustrated by his inability to help Madeline, Denton shifts into a more investigative role, attempting to reconcile the inexplicable with known medical science.

His vivid nightmares—rooted in battlefield trauma—add a psychological depth that mirrors the physical decay occurring around him. Denton’s growing recognition of the fungal threat shows his evolution from a clinician to a man grappling with the existential horror of life and death blurred by parasitism.

His final collaboration with Potter to document the fungus’s biology underscores his commitment to truth, even when it challenges his understanding of life itself.

Angus

Angus, Easton’s devoted orderlie, functions as both comic relief and emotional anchor. His blunt common sense and superstitious beliefs, such as warnings about “witch-hares,” provide a stark contrast to the intellectual approaches of Potter and Denton.

Yet Angus’s instincts often prove prescient, giving voice to the local folklore that underpins the novel’s atmosphere of dread. His loyalty to Easton is unwavering, and he acts as a moral conscience in several key moments.

Angus’s grounded nature and emotional clarity help balance the novel’s descent into madness, offering the reader a touchstone of normalcy in an increasingly alien environment.

Themes

Fungal Parasitism and Biological Invasion

At the core of the novel lies a chilling exploration of fungal parasitism—a concept drawn from real-life biology and transformed into a source of supernatural terror. The story introduces the possibility of a parasitic fungus that mimics the functions of the human nervous system to animate corpses, echoing the behaviors of Cordyceps fungi that infect insects.

As this concept unfolds, it escalates from strange hares behaving puppet-like to the slow, horrifying revelation that Madeline and perhaps Roderick are being puppeteered by the same fungal agent. This theme is profoundly unsettling because it blurs the line between life and death, autonomy and control.

The fungus does not merely kill; it preserves, replicates, and impersonates. The victims do not rot or rest—they move, speak, and interact in grotesque simulations of life.

T. Kingfisher magnifies the horror by suggesting that the body can become a mere shell while the real person—the consciousness, the will, the soul—is suppressed or extinguished. Moreover, the setting itself becomes complicit: the house is infested, the lake pulses with luminous fungal blooms, and even the natural order is undermined.

This is not a simple infection; it is an ecosystem-wide invasion. It questions the sanctity of the human body and raises fears not of death, but of what may persist afterward—an alien intelligence mimicking humanity in grotesque approximation.

By grounding this horror in scientific plausibility, Kingfisher adds weight to the fear, making it intimate and believable.

Loss of Identity and Bodily Autonomy

The erosion of identity and autonomy is a deeply disturbing element throughout the novel, exemplified most vividly in Madeline’s degeneration. Her body becomes lighter, colder, and ultimately begins to display behavior detached from human experience—smiling without emotion, speech marked by confusion, and movements that seem choreographed rather than intentional.

What is most terrifying is not that she is dying, but that she is being overtaken from within. Her actions and thoughts no longer belong to her but to something else that has invaded and subdued her being.

Roderick’s descent into paranoia and hallucination can be interpreted similarly—not as mere madness, but as early symptoms of a slow mental occupation. The horror is psychological as much as physical; the characters are aware, to varying degrees, of their loss of self.

This awareness is crueler than death itself, as it denies them even the dignity of understanding their own transformation. Kingfisher’s portrayal of these characters does not sensationalize their condition; instead, it draws the reader into the intimate tragedy of watching a personality erode, overwritten by a fungal consciousness that has no empathy or individuality.

The idea that one’s body could move, speak, and act without the permission or presence of the person it once belonged to is profoundly terrifying. It challenges notions of the self and underscores how easily the essence of a person—what makes them them—can be erased by an uncaring biological force.

The Natural World as a Source of Horror

While many horror stories rely on the supernatural, What Moves the Dead roots its terror in the natural world, particularly in mycology—the study of fungi. This grounded approach makes the horror more plausible and thus more effective.

The local environment is not just a backdrop; it is an active participant in the nightmare. The flora, fauna, and even water are shown to be contaminated, pulsing with malevolent fungal life.

Hares drag their bodies unnaturally, fish exhibit parasitic filaments, and the estate itself seems to rot from within. The lake, with its phosphorescent lights and hidden organisms, becomes a symbol of corrupted nature—still, reflective, and hiding something monstrous beneath.

Unlike ghosts or demons, fungi are real and omnipresent, capable of profound biological manipulation. The novel leverages this truth to unsettling effect, turning nature into something both alien and predatory.

Even Potter, the scientifically-minded mycologist, is unnerved by what she discovers, highlighting how science offers explanation but not comfort. The story subtly suggests that nature is not always benevolent or neutral—it can be a host to forces that consume and control.

This idea reverses the common human perspective of dominion over nature; in What Moves the Dead, it is nature that colonizes the human, making flesh just another ecosystem to inhabit. The result is a chilling reminder of how small and vulnerable human beings truly are in the face of evolutionarily ancient, adaptable lifeforms.

Rationality Versus Folklore

A prominent thematic tension in the novel lies between scientific rationality and local folklore. Characters like Eugenia Potter and James Denton represent the rationalist approach, seeking biological explanations for the strange phenomena at the Usher estate.

In contrast, locals speak of witch-hares and haunted lakes, tapping into folkloric traditions that attribute the uncanny to supernatural causes. This conflict is not merely academic; it reflects differing ways of making sense of terror.

As the evidence mounts—bizarre animal behavior, eerie lights, and Madeline’s resurrection—it becomes clear that the scientific and the folkloric are not mutually exclusive but rather two lenses on the same phenomenon. The fungus is real, observable, and potentially classifiable, but its effects manifest in ways that seem mythic or cursed.

This convergence blurs the boundary between what can be explained and what must be feared. Moreover, it raises questions about the limits of knowledge: can science truly encompass all phenomena, or are there aspects of existence that resist empirical categorization?

Kingfisher does not undermine science; rather, she suggests that rationality and folklore may both hold partial truths. In moments where Potter and Denton are baffled, it is often the folklore that provides the emotional or thematic resonance needed to confront the horror.

The villagers’ warnings, once dismissed as superstition, gain a grim legitimacy. This theme enriches the narrative by acknowledging that terror often lies not just in what is unknown, but in what is known too late or ignored too long.

Sacrifice and Moral Responsibility

As the narrative progresses toward its climax, the theme of sacrifice and moral responsibility emerges with increasing clarity. Easton, Denton, and Potter are faced with impossible decisions: how to save those infected, how to contain the spread of the fungus, and whether it is permissible to destroy the estate and its remaining inhabitants.

These decisions are not made lightly. They are weighed down by guilt, loyalty, and the emotional toll of witnessing human beings turned into vessels for a parasitic lifeform.

The destruction of the Usher estate, while framed as a necessary act, is also a symbolic purification—a recognition that the horror has spread too deeply to be excised through conventional means. The fire becomes an act of both mercy and violence, meant to halt further contamination but also to acknowledge the futility of saving those already consumed.

Roderick’s choice to remain behind and die with the house adds a tragic dimension to this theme; he embraces the end, admitting that his humanity is already lost. The survivors, particularly Easton, carry the psychological burden of their choices.

The decision to mask the true nature of the events in future scientific reporting reflects a compromise between truth and pragmatism. This theme resonates beyond the scope of the narrative, touching on broader ethical questions about what must be done to prevent catastrophe, the price of knowledge, and the loneliness of those who survive such choices.

It leaves the reader with a sense of sorrowful reflection rather than triumph.