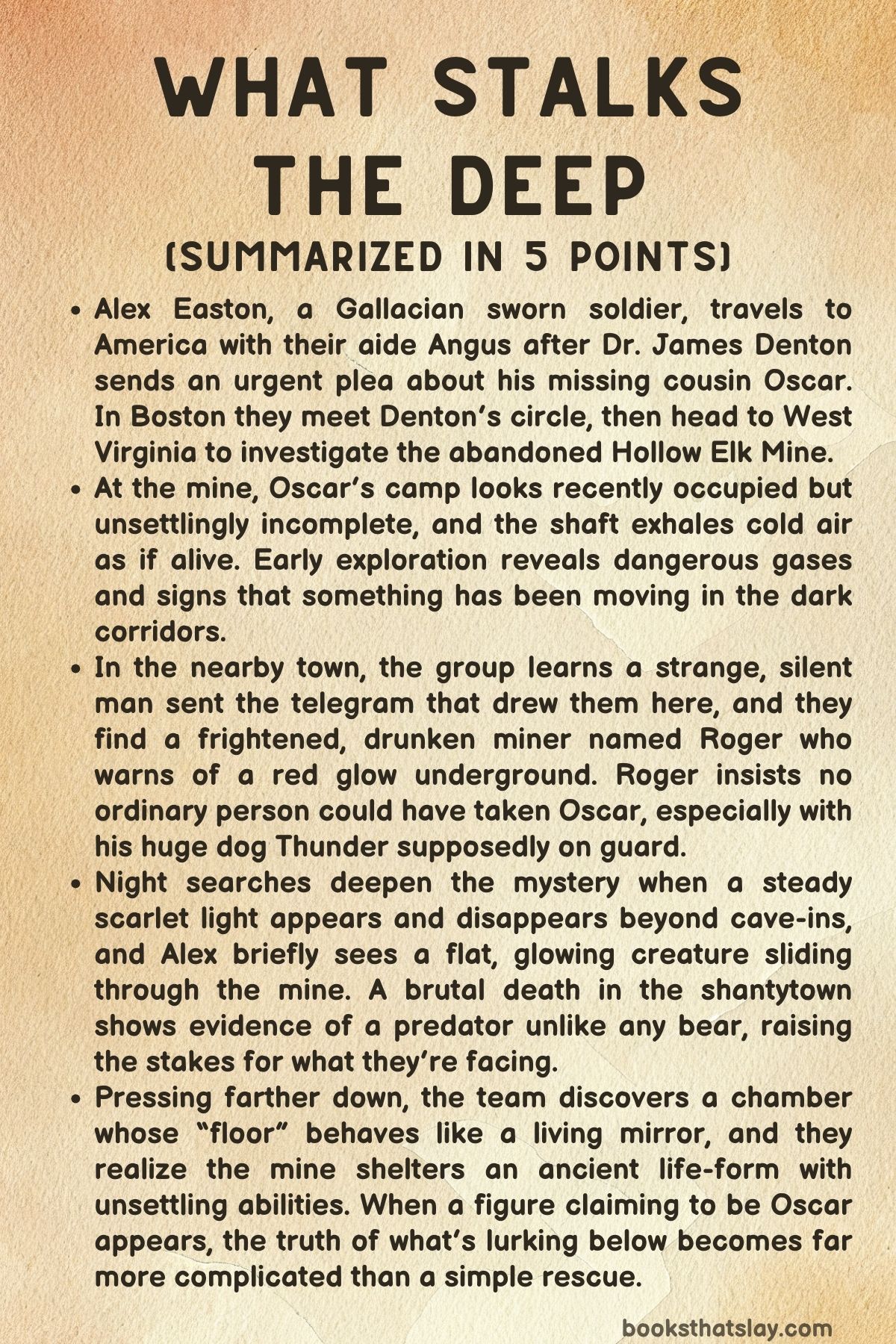

What Stalks the Deep Summary, Characters and Themes

What Stalks the Deep by T. Kingfisher is a claustrophobic, old-school horror adventure set in early-20th-century America.

It follows Alex Easton, a Gallacian sworn soldier with a history of surviving the uncanny, who is pulled into a mystery in the coal country of West Virginia. A vanished cousin, a mine that seems to breathe, and a red light far underground draw Easton and a small group of friends into a place where geology, gas, and something not quite animal all collide. The story mixes field investigation, tight camaraderie, and escalating dread, then pivots into a strange, thoughtful encounter with an ancient nonhuman life. It’s the 3rd book in the Sworn Soldier series by the author.

Summary

Alex Easton, a sworn soldier from Gallacia, arrives in Boston with their aide Angus after receiving an urgent telegram from Dr. James Denton.

Easton and Denton share a past brush with the supernatural, so the message carries weight. Denton introduces Easton to two men who will join the trip: Kent, his practical assistant, and John Ingold, a chemist with a clipped manner and a curious mind.

Denton explains that his cousin Oscar has disappeared in West Virginia. Oscar went to check on Hollow Elk Mine, an old Denton family coal mine that was abandoned years earlier after miners reported strange lights deep inside.

He has not returned, and Denton is unwilling to wait for local authorities who may never search properly.

The party travels by train into West Virginia, then hires horses in the rough town of Shaversville and rides into the hills. The mine sits in a cold, quiet hollow, its entrance wide enough to swallow all their lantern light.

Oscar’s camp is set up in a small office near the shaft. It looks recently used, as if someone stepped away briefly and meant to come back.

Yet there is only one bed. The gear of Roger Clement, a local hired hand who had been with Oscar, is missing, though food remains on the table.

Easton notices the air sliding out of the mine in strong gusts, like lungs exhaling.

They go inside to get a sense of the place. The descent is slick and steep.

Ingold tests the air and finds traces of firedamp and pockets of blackdamp—deadly gases that can suffocate or explode. They retreat and agree to return with a clearer plan, mapping what they can while staying cautious.

In nearby Flatwoods they ask questions. At the telegraph office, Ingold and Easton learn something unsettling: the telegram that summoned them was sent by a tall man in miner’s goggles and a helmet who did not speak.

He communicated by writing on a slate and paid heavily. The clerk recalls his silence more than anything else.

Meanwhile Denton and Angus search the derelict shantytown outside town and find Roger Clement. Roger is drunk, frightened, and full of dread.

He says Oscar went back into the mine after seeing a red light far below, and never came out. Roger insists that no ordinary thief or rival miner took him; Roger’s enormous dog Thunder would have detected anyone nearby.

His terror seems genuine.

Back at camp, Easton and Ingold return underground to map the third level. Lower tunnels are flooded with foul water, and the air turns thin and wrong.

As Ingold measures side passages, Easton hears a wet slapping echo that seems to trail behind them, then somehow stays ahead, closer to the exit. They take a narrow detour and Easton is hit by firedamp, growing dizzy and confused.

Ingold drags them back to cleaner air. Both are shaken, sure that something mobile is in the dark with them.

That night they descend again. A steady red glow appears deep down a tunnel, strong enough to stain the rock.

Denton orders all lanterns lowered, and they creep forward. The glow vanishes when Denton steps onto rubble near a cave-in.

Immediately the wet slapping returns just beyond the fall, then withdraws. Crawling through loose rock, they find miner’s clothing laid face-down as if an empty body had been pressed into the stone.

A receipt in one pocket shows the clothes belonged to the silent man who sent the telegram. Another collapse blocks further progress, so they pull back.

In the morning, a note has been left at the camp warning them to leave because the mine is unsafe for “humans. ” The wording feels like it came from someone outside their group, but not from a local miner either.

Denton and Ingold clear most of the second collapse and expose a sloping passage leading still deeper. They decide to ventilate it before entering.

That night Easton again sees the red glow. This time they glimpse a flat, ribbon-like creature lit from within, sliding across the shaft.

On top of it rides a half-melted human-shaped form, as if the creature is trying to carry someone’s outline. When Easton looks harder, it goes dark and is gone.

Before they can act on that sighting, a man named Elijah from the shantytown arrives in panic. He says a bear attacked, and Louisa is badly injured.

Denton, Ingold, and Easton rush over. Denton stabilizes Louisa’s mangled arm, but the scene outside does not fit a bear kill.

The dead miner, Lee Mason, has been opened cleanly, organs removed with a terrible neatness. His trousers are unbuttoned in a way that suggests handling, not an animal tearing.

Easton tries to find Roger and Thunder afterward but hears no answer and notes Thunder’s unnatural silence.

Exhaustion and fear push the group toward a decision. After a grim night, Easton wakes to find Denton already in the mine, obsessively clearing rubble.

Easton and Angus follow him, refusing to let him go alone. Denton announces he has opened the blocked way and will press on to find Oscar.

The new passage runs downward until it ends at a wall, but Denton discovers a narrow spiral crawlspace. Ingold and Easton warn that it is too tight to turn around in, and any gas pocket or rockfall would trap a person to die.

Denton insists, driven by loyalty to the cousin who once saved his life, and goes alone. The others wait above, counting their breaths.

Denton returns after a long stretch and says the spiral opens into a chamber. They crawl down and enter a limestone room whose “floor” is hard, pearl-like, and faintly luminous.

A rusted drill stands there from an earlier attempt to cut through. Easton notices something wrong in the reflections beneath their feet: the surface mimics them, but motions lag and reverse as if it is thinking about what it sees.

When Ingold brings a lantern close, color pulses through the shell. He realizes the floor is alive—a vast shelled organism that imitates shapes above it.

The red glow in the mine has been part of its presence, and the slap of movement has come from something else interacting with it.

As they regroup, Denton runs down a side tunnel, convinced he is chasing a man. Easton follows and they find “Oscar” alive.

Denton embraces him, but Oscar cannot speak; his throat is burned by mine gas. He writes on a slate that unknown men chased him and he got lost.

Angus, suspicious, orders him to remove his goggles. Oscar’s eyes are blank, skin-colored, and slowly shifting pigment tries to form crude eyes.

Ingold recognizes the same mimicry from the living floor. The being admits it is not Oscar.

It has copied his shape so they would listen. It calls itself Fragment and communicates only through writing.

Fragment gives them a letter explaining that its people have slept beneath the mine for ages and want to be left alone. Blasting and drilling threaten to break their larger body into damaging pieces.

It asks for help and news of the outside world. Ingold questions it gently.

Fragment explains it is part of a huge collective “wholeness,” a single organism able to split into smaller parts and later rejoin, sharing memory. Long ago its kind floated as immense gelatinous sheets on the ocean surface, feeding on tiny sea life.

During an Ice Age, this wholeness traveled inland through rivers into caves to avoid freezing and left one sentry awake to watch and forage.

Denton suspects Fragment has killed Oscar and the dead miners, while Ingold argues Fragment seems curious and frightened rather than predatory. They plan to leave, but that night something large injures a horse.

The next day Roger arrives with Thunder. In the shaft, Thunder abruptly attacks Easton.

Under Easton’s headlamp the dog’s chest splits into a second mouth of bone and flesh. The sentry has been impersonating Thunder.

Bullets barely slow it. Ingold smashes an oil lamp over the creature to burn it, and Fragment throws itself around the wounded sentry, trying to merge and calm it.

Denton nearly sets both on fire, but Easton and Ingold stop him.

A larger mass of the sentry erupts from another shaft, a moving wall of flesh swollen with stolen meat. Easton flees into a low firedamp passage, but the creature overtakes them and smothers their face.

Easton sparks a lighter. The firedamp explodes, collapsing rock and killing the sentry.

In the choking aftermath, Fragment tunnels through the burning remains and seals itself over Easton’s mouth, giving them air until the others dig them out. In the charred debris they find Oscar’s ring, confirming Oscar was killed by the sentry.

With the threat ended, grief and responsibility settle in. The men choose to help Fragment return to its sleeping wholeness.

They obtain a diamond core bit and drill through the living shell without explosives, careful not to harm the organism. Fragment rejoins the larger body below, and new sentries are set to guard the mine without hunting humans.

Roger remains behind, paid by Denton to seal and watch the entrance. Easton, bruised and shaken but alive, leaves West Virginia with the others, carrying the secret of what lies under Hollow Elk and the heavy knowledge of what was lost there.

Characters

Alex Easton

Alex Easton is the story’s anchor and lens, a Gallacian sworn soldier whose training makes them steady in crisis but not numb to wonder. Their identity as a professional protector shapes how they move through America: always alert, mapping spaces, monitoring people, and taking responsibility even when no one asked.

Easton’s courage is practical rather than dramatic; they keep going even while afraid, and their fear registers as a useful signal instead of paralysis. What makes Easton especially compelling is the mix of martial discipline and genuine empathy.

They don’t treat the mine as a puzzle to conquer, but as a living danger to be respected, and they extend that same ethical curiosity to Fragment once they realize it’s a person-like being rather than a monster. Easton’s near-death experience and willingness to risk themselves to stop the sentry crystallize their role as a guardian who chooses sacrifice for others, but their survival also underlines a theme of reciprocity: protecting others invites protection in return, and Fragment’s act of sealing air to Easton’s mouth is the narrative mirror of Easton’s earlier refusal to kill without understanding.

Angus

Angus serves as Easton’s aide and moral counterweight, embodying loyalty, pragmatism, and the hard edge of past trauma. He’s the most instinctively suspicious member of the group, often approaching unknowns through the logic of threat assessment rather than curiosity.

That caution isn’t pettiness; it’s the posture of someone who has seen too many “impossible” things go fatal. Angus’s competence is quiet but constant: he handles logistics, keeps watch, and steps in when Easton is incapacitated.

His distrust of the supposed Oscar and readiness to use a pistol show how he prioritizes survival over sentiment, yet he isn’t cruel—he is protecting the team from a danger they don’t yet understand. Over the course of events, Angus is forced to recalibrate what a “nonhuman” threat looks like, learning that some strange things can be negotiated with while others must be destroyed.

He ends the story still vigilant, but more willing to accept Easton’s ethic of restraint, suggesting a subtle growth from reflexive suspicion to discerning judgment.

Dr. James Denton

Dr. James Denton is the emotional engine of the plot, a man of science driven by love, guilt, and a need to repay old debts.

His urgent telegram and insistence on searching Hollow Elk Mine come from personal stakes—Oscar once saved his life, so Denton’s pursuit is partly an attempt to restore a moral balance he feels is broken. That devotion makes him brave, but also dangerously single-minded.

Denton’s scientific identity is real, yet in crisis it warps into obsession: clearing rubble alone, pushing deeper, and clinging to any hope that his cousin lives. Even after meeting Fragment, Denton struggles to see beyond his grief, suspecting it of murder because he needs a culprit and can’t bear randomness.

His near decision to burn Fragment with the sentry shows how grief can eclipse ethics. Still, Denton is not a villain; he’s a portrait of a good man temporarily overwhelmed by loss.

The ending, where he chooses to help drill safely and reunite Fragment with the wholeness, suggests that once his grief is given truth—Oscar’s confirmed death—he regains the humane clarity to act responsibly toward the living.

John Ingold

John Ingold, the chemist, represents measured curiosity and the best version of rational inquiry in the book. Unlike Denton, Ingold’s science doesn’t narrow his perspective; it expands it.

He is cautious with evidence, attentive to environmental hazards like firedamp and blackdamp, and willing to revise his beliefs as new data appears. Ingold’s most defining moment is his recognition that the “floor” is alive, which reframes the mine from a haunted space into an ecosystem with ancient inhabitants.

He becomes the group’s translator between human fear and nonhuman reality, questioning Fragment not to dominate it but to understand its history and needs. Ingold also has decisive courage: when Thunder’s impersonator attacks, he burns it, choosing the necessary violence without hesitation or cruelty.

His balance of empathy and action is crucial to the group’s survival and to the ethical resolution. In many ways, Ingold is the story’s intellectual conscience, demonstrating that science can be a tool for compassion rather than conquest.

Kent

Kent, Denton’s assistant, plays a smaller but clarifying role as the bridge between Boston’s professional world and the mine’s raw danger. In the early portion, Kent helps establish Denton’s credibility and networks, emphasizing that the expedition is not reckless adventurism but a deliberate response to a trusted call for help.

Kent’s limited presence also functions narratively: he represents the ordinary life the others step away from. By remaining behind, he highlights how far the main group travels—geographically and existentially—into a realm where familiar rules dissolve.

Oscar Denton

Oscar is mostly absent, yet his shadow defines much of the story’s momentum. Through Denton’s memories and Roger’s fear, Oscar emerges as capable, determined, and perhaps more willing than others to go alone into danger.

His disappearance and later confirmation of death embody the cost of curiosity in hostile, uncharted spaces. When Fragment mimics him, Oscar’s identity becomes a tool and a tragedy at once: the mimicry is both a lure for communication and a reminder of what has been lost.

Finding his ring in the sentry’s remains provides a grim finality, turning Oscar into the story’s moral pivot—his death demands a response, but not a simplistic one, because the true killer isn’t the first “monster” the humans meet.

Roger Clement

Roger Clement is the mine’s human casualty who survives long enough to testify, a man broken by fear and alcohol yet still holding vital truth. His drunkenness is less comic relief than psychological fallout from witnessing something he can’t name.

Roger’s loyalty to Oscar seems genuine, and his insistence that no ordinary thief could have entered unnoticed because of Thunder shows he’s trying to make sense of events within the limits of what he trusts. His terror of the red light and refusal to re-enter the mine underline how the supernatural here is not thrilling but annihilating to the unprepared.

By the end, Roger’s role shifts from helpless witness to reluctant guardian; staying behind to seal and watch the entrance suggests a man seeking redemption through duty, even if the duty terrifies him.

Thunder

Thunder begins as a symbol of security in Roger’s story—an enormous dog that should have detected any intruder—then becomes the cruelest reveal of betrayal. The sentry’s impersonation of Thunder weaponizes trust; what the humans see as a loyal animal is in fact an infiltrator learning their habits.

The grotesque second mouth opening in its chest emphasizes the theme of reality splitting open to show something older and less human underneath. This sentry is not curious like Fragment; it is hungry, predatory, and adaptive, feeding on humans and animals to grow.

Its method of killing—precise removal of organs, opportunistic attacks, stealth—marks it as an apex hunter in the mine’s ecosystem. The sentry embodies the nightmare side of the wholeness: not the collective intelligence sleeping below, but a fragment gone feral, driven by appetite and self-preservation.

Fragment

Fragment is the story’s most morally complex nonhuman character, a being both alien and deeply relatable. Its defining trait is partialness: it is literally a separated piece of something larger, with the loneliness, curiosity, and memory-loss that implies.

Fragment’s mimicry isn’t deceit for harm, but a limited language—copying shapes and colors because that’s how its body communicates. It wants contact with humans not out of conquest but out of need: to understand the danger threatening its people and to ask for help preventing “fragmentation” from mining blasts.

Fragment’s gentleness contrasts sharply with the sentry’s violence, showing that otherness doesn’t equal hostility. Its attempt to merge with the wounded sentry reads as instinctive compassion or responsibility toward its kin, even when that kin is monstrous.

Most importantly, Fragment repays human mercy with literal life-saving aid, protecting Easton from suffocation and facilitating a safe reunion with the wholeness. It stands for the possibility of coexistence if approached with patience and humility.

The Wholeness (Collective Organism)

The wholeness is less a character in the ordinary sense than a vast presence, but it still functions as a personality at scale. It represents deep time, ecological memory, and a mode of life that defies human individuality.

The idea that it once lived as ocean-surface sheets feeding on microscopic life paints it as ancient, patient, and fundamentally non-aggressive—more like a drifting continent of flesh than a predator. Its ability to split, rejoin, and share memory suggests a communal identity where separation is injury and reunion is healing.

Sleeping beneath the mine, it is vulnerable to human industry, not because it is weak, but because it is indifferent to human timelines until the blasting threatens to tear it apart. The wholeness symbolizes nature too old to fit human categories of monster or marvel, and the group’s decision to keep it secret is an acknowledgment that some wonders survive only if untouched.

Elijah

Elijah, from the shantytown, is a minor figure who still sharpens the story’s social texture. He represents the local community living in precarity around the mine’s ruins, people whom industry has abandoned long before any supernatural danger arrived.

His frantic request for help after the supposed bear attack emphasizes how the mine’s horror spills into human poverty, targeting those least protected. Elijah is a reminder that the threat is not an abstract mystery but a force ruining real lives.

Louisa

Louisa appears briefly but powerfully through injury. Her mangled arm and Denton’s attempt to save it place human suffering in the foreground, preventing the story from drifting into pure monster-hunt spectacle.

Louisa’s victimization also reinforces the sentry’s predatory reach beyond the mine. She stands for the innocent collateral of ancient forces meeting modern exploitation.

Lee Mason

Lee Mason’s corpse is a key moment of revelation about the enemy’s nature. The precise removal of his organs and the unsettling detail of his unbuttoned trousers signal intelligence and method rather than animal rage.

Lee functions as evidence more than personality, but his death shifts the group’s understanding from folklore about strange lights to the reality of a calculated hunter. In narrative terms, he is the grim proof that the mine’s threat is escalating and that the humans are no longer merely searching, but being hunted.

Themes

Encountering the Unknown Without Owning It

From the moment Alex Easton reaches West Virginia, the story presents the unknown as something that cannot be handled through ordinary categories like “resource,” “enemy,” or “property. ” The mine is a human space—mapped, titled, inherited, and worked—yet it holds a reality older than the family claim.

What appears at first as an intrusion into human life gradually flips into a recognition that humans are the intruders into a much deeper ecology. The wholeness and Fragment are not demons staged for conquest, nor hidden treasure to be extracted.

They are living beings with their own history, needs, and limits. The red glow, the breathing drafts of the shaft, and the floor that copies reflections are all signs that the mine is not inert ground but a habitat.

Horror grows from misreading that habitat, especially when Denton treats the mine like a puzzle that must yield to human will. The narrative refuses the familiar logic of “discover → control → explain away.

” Instead, it insists on “discover → listen → decide what you are allowed to do next. ” Fragment’s letter is crucial because it gives voice to the inhuman without making it human.

It does not ask for friendship or moral approval; it asks for space and safety. The group’s final choice to drill carefully rather than blast is a moral turning point: they adapt themselves to what they have found rather than forcing what they found to adapt to them.

Even the act of keeping the wholeness secret reinforces this theme. Easton and Ingold understand that knowledge can be a weapon in a society built on extraction, and that some truths must be protected from the structures that would exploit them.

In What stalks the deep, the unknown is not valuable because it can be mastered; it is valuable because it exposes how small human jurisdiction really is, and it demands a different kind of response—restraint, curiosity, and a willingness to leave something whole instead of breaking it into human-sized pieces.

Devotion, Guilt, and the Risk of Obsession

The story treats loyalty as both a strength and a danger, especially through Denton. His determination to find Oscar is not casual affection; it is grounded in a past debt, a life once saved, an emotional ledger that he feels must be balanced.

This makes his search noble, but also makes him vulnerable to a narrowing of judgment. Every warning from the mine—gas pockets, cave-ins, the unsteady red light—should slow him.

Instead, they sharpen his urgency. The more hazardous the space becomes, the more he feels morally required to push forward, because turning back would mean failing the person who once rescued him.

That pressure doesn’t read like selfishness; it reads like grief arriving early, before the loss is even confirmed. In contrast, Easton’s loyalty is duty shaped by experience.

Easton responds to danger by checking air quality, listening to sounds, and refusing tight passages that could trap a body. Their devotion is steady rather than consuming.

Angus fits a third angle: he is loyal to Easton and to the idea of survival, which makes his suspicion of the false Oscar immediate and practical. These different kinds of loyalty collide in the cave, where Denton’s emotional certainty almost overrides the group’s physical safety.

Later, when Fragment attempts to heal or merge with the injured sentry, Denton’s suspicion again threatens to become absolutist. He is ready to burn both creatures because grief makes nuance feel like weakness.

The theme here is not “love is bad,” but that love mixed with guilt can become a force that ignores evidence. The narrative shows that obsession is not a personality defect; it is loyalty with no remaining room for uncertainty.

Denton’s arc is tragic because it is understandable, and the book doesn’t mock him for it. Instead, it shows how a single moral focus—repaying a debt—can erase the wider moral field, including care for the living and the unknown.

What stalks the deep ultimately argues that devotion must be paired with humility, or it will turn into a kind of tunnel vision as suffocating as blackdamp.

Identity as Pattern, Not Surface

The mine’s creatures make identity unstable in a way that is unsettling but also philosophically pointed. Fragment copies what it sees: reflections in reverse, pigments shifting toward human form, a face trying to invent eyes.

The sentry does the same but with predatory intent, hiding inside a dog’s body and later swelling into a massive feeding wall. These acts are not just scares; they are examinations of what makes someone real.

When Denton finds “Oscar,” the reunion is emotional because the surface cues match memory. Yet surface cues fail instantly under scrutiny.

The false Oscar cannot speak; it writes. Its eyes are wrong.

Its skin tries to correct itself like wet paint seeking a template. The scene emphasizes that identity is not a costume you can wear convincingly forever.

It is a continuity of mind, voice, and mutual recognition. The impostor can reproduce shape, but it cannot reproduce lived connection.

Even before the reveal, Angus senses this. His distrust is not mystical; it is social intuition that something essential is missing behind the mimicry.

At the same time, the book complicates the easy horror rule that “impostor equals evil. ” Fragment is a mimic, but not a liar in the human sense.

It copies as a way to communicate across species. The sentry copies as a way to hunt.

So mimicry becomes morally neutral; what matters is intention and relationship. Easton’s own identity adds another layer.

As a Gallacian sworn soldier using they/them pronouns, Easton lives in a world where identity is already tied to role, oath, and self-definition rather than a single biological script. Their steadiness against the mine’s distortions highlights a contrast: humans can choose who they are through memory and moral commitment, while the inhuman copies without fully understanding personhood.

Yet the wholeness complicates even human certainty. If a being can split, share memory, and rejoin, then identity is a distributed pattern rather than a single body.

The wholeness is not “one creature” in the human sense; it is a collective self. That pushes the characters—and the reader—to accept that personhood might exist outside the boundaries people usually assume.

In What stalks the deep, identity is shown as something rooted in continuity, purpose, and mutual acknowledgment, not just shape. The horror comes from losing that grounding, and the hope comes from recognizing new forms of selfhood without erasing their difference.

Extraction, Consequences, and Moral Repair

Coal mines are already loaded symbols: places where wealth is pulled from the ground at human cost. The story uses Hollow Elk Mine to test the ethics of extraction beyond the human realm.

The family mine was abandoned because of “strange lights,” but the deeper truth is that it was abandoned because human activity had disturbed something living. Fragment’s fear of “fragmentation” is a direct reference to blasting, drilling, and the industrial habit of treating underground space as lifeless matter.

Even before the supernatural is confirmed, the environment signals danger through firedamp and blackdamp—natural forces that punish carelessness. Once the creatures are known, those gases become part of a broader moral landscape.

Humans have already reshaped this place; they left tools, tunnels, debris, and death. The sentry’s growth through stolen flesh is a grotesque mirror of human extraction: both involve taking bodies—animal, mineral, human—and turning them into fuel for survival or profit.

The difference is that humans encode extraction as normal. The story forces the characters to see extraction from the outside, as something that can end a civilization that has slept there for ages.

The ethical shift happens when the men decide not to destroy Fragment, not to dynamite the shell, and not to claim the wholeness as a trophy discovery. They choose a slower, more expensive, careful method—diamond drilling—precisely because it avoids further harm.

Repair here is not sentimental. They cannot resurrect Oscar or undo the mine’s original intrusion, but they can refuse to repeat it.

Roger’s new role as guardian rather than prospector also matters: he becomes a human boundary that prevents further exploitation. Keeping the secret extends repair into the future, acknowledging that the world above would likely translate discovery into profit and weaponry.

The theme suggests that moral action is not only about bravery in a crisis; it is about recognizing the long shadow of human habits and choosing restraint even when you could choose conquest. In What stalks the deep, repair is portrayed as a series of deliberate limits—don’t blast, don’t expose, don’t take what isn’t yours.

The mine becomes a lesson that survival and progress cannot be measured only by what humans gain, but also by what they decide to leave untouched.

Cooperation Across Difference in a Crisis

The group that enters the mine is already a patchwork of backgrounds and skills—soldier, doctor, chemist, aide, local laborers—and the story repeatedly shows that none of those roles is sufficient alone. Easton’s training keeps them alive in gas-filled tunnels.

Ingold’s scientific attention allows the living floor to be recognized rather than dismissed as illusion. Denton’s medical skill saves Louisa’s arm and prevents more death in the shantytown.

Angus’s suspicion challenges false assumptions and protects the group from manipulation. Every survival moment depends on shared competence and argument, not on a single hero.

What makes this theme interesting is that cooperation is not always smooth or polite. The group disagrees constantly about risk, ethics, and interpretation.

Denton wants to push forward; Easton and Ingold resist. Angus distrusts “Oscar” when Denton wants to believe.

These conflicts are not distractions; they are the method by which truth is reached. The story values disagreement as a safety tool.

It also expands cooperation beyond humans. Fragment acts as both witness and rescuer, enclosing the sentry to stop it and later sealing over Easton’s mouth to provide air.

This is not friendship in a human sense; Fragment doesn’t adopt human values. But it recognizes reciprocal need.

Humans protect Fragment from Denton’s panic; Fragment protects humans from suffocation. Crisis makes the boundaries between species practical rather than ideological.

Trust is constructed through action: who helps, who harms, who listens. By the end, the men are not “allies” of the wholeness in a grand political sense; they are participants in a temporary, necessary agreement to prevent further bloodshed.

The new sentries set by the wholeness and the human sealing of the entrance show a layered defense system built through mutual recognition, not domination. What stalks the deep portrays cooperation as something earned by seeing others clearly—humans with different motivations, and nonhumans with different forms of life—and then choosing action that protects the shared space.

In a setting defined by darkness and danger, the most reliable light comes from collective reasoning and the willingness to accept help from beings who do not look, speak, or live like you.