When Women Were Dragons Summary, Characters and Themes

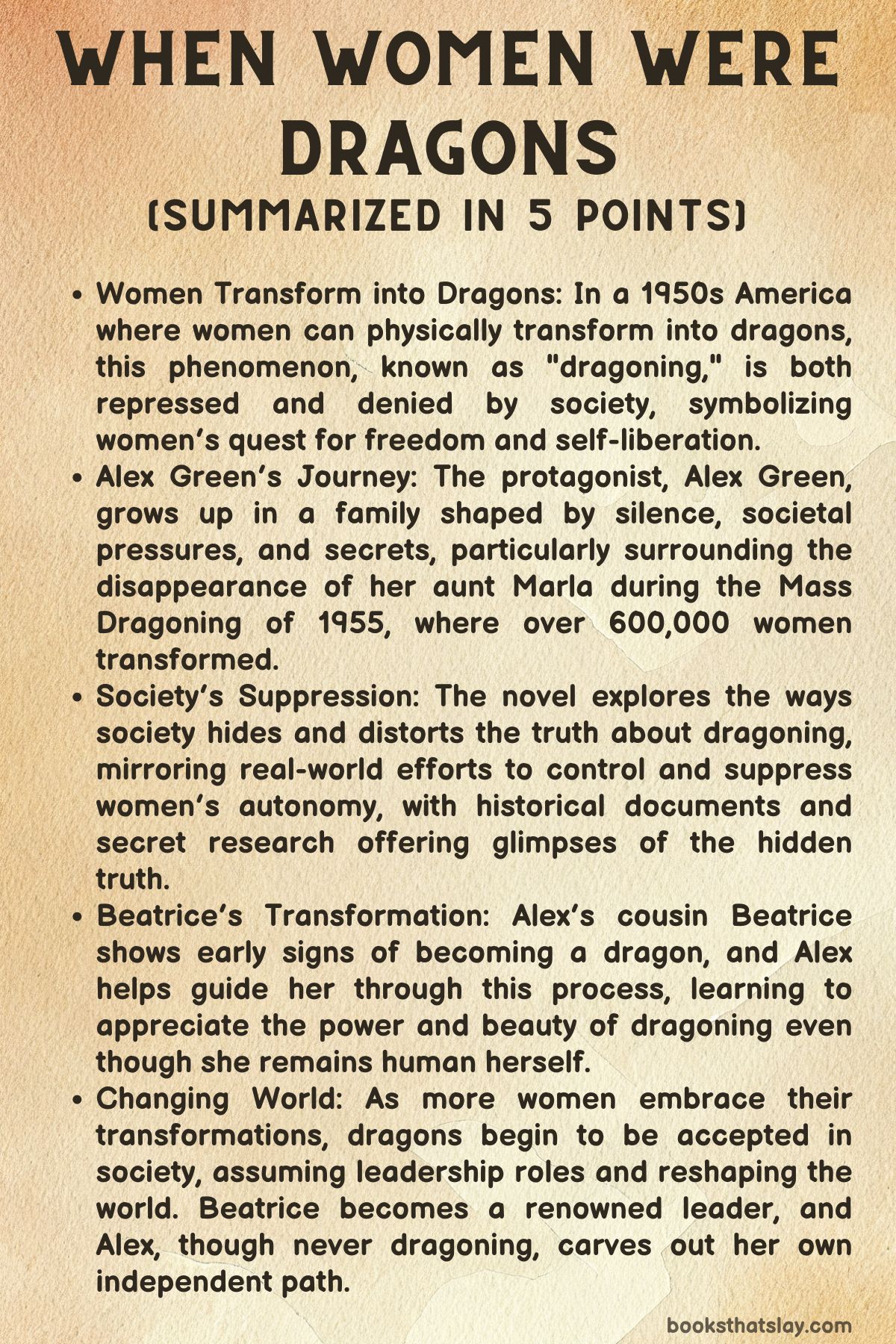

When Women Were Dragons by Kelly Barnhill, published in 2022, is a speculative fiction novel that imagines a world where women have the ability to transform into dragons. Set against the backdrop of 1950s America, the novel explores themes of gender, power, and freedom through the experiences of Alex Green, who witnesses both personal and societal upheavals.

The novel blends elements of memoir, history, and fantasy, weaving together the struggles of women who are repressed and forced to conform, but who find an explosive outlet in the act of “dragoning”—transforming into their true, liberated selves.

Summary

Alex Green’s life unfolds in a familiar yet fantastical version of 1950s America, where women can transform into dragons—a fact that society desperately tries to suppress.

As a young girl growing up in Wisconsin, Alex witnesses her mother’s mysterious illness, her father’s emotional distance, and her aunt Marla’s departure, all while grappling with unspoken truths.

The transformation of women into dragons is rarely discussed, much like cancer, which afflicts her mother. Yet, both phenomena hover over Alex’s world like shadowy secrets.

The turning point comes during the “Mass Dragoning” event on April 25, 1955, when hundreds of thousands of women across the country shed their human forms and become dragons, leaving behind their families and lives. Among them is Marla, who disappears, leaving her daughter Beatrice behind.

As her family splinters, Alex grows up in an atmosphere of silence, her questions about dragoning brushed aside by the adults around her.

When her mother succumbs to cancer during Alex’s teenage years, her father quickly moves on, relegating Alex and Beatrice to a cramped apartment so he can start a new life with his second wife.

Now responsible for her young cousin, Alex is forced to take on adult roles she’s ill-prepared for, learning to navigate a world that refuses to acknowledge the reality of dragons.

In time, Alex finds solace and guidance through Mrs. Gyzinska, a fiercely intelligent librarian who introduces her to secret knowledge hidden by scholars like Dr. Henry Gantz.

These figures work to uncover the truth about dragoning, an event that has been obscured and denied by the government and media.

Through their influence, Alex gains a deeper understanding of the transformation process, coming to realize that dragoning is not merely a destructive act but one of liberation, driven by a desire for freedom from the constraints of patriarchal society.

Meanwhile, Beatrice begins showing signs of her own impending transformation. Unlike Alex, who remains human throughout, Beatrice is destined to become a dragon.

When their Aunt Marla returns, now a dragon herself, Alex is forced to confront the power and beauty of this change.

Though Alex grapples with her own fears and uncertainties, she helps Beatrice navigate the challenges of dragoning, guiding her toward self-acceptance and freedom.

As dragoning becomes increasingly recognized, societal attitudes shift. Alex witnesses how dragons slowly integrate into everyday life, holding positions of power and influence.

While she chooses not to transform herself, Alex supports Beatrice’s journey, ultimately watching her cousin become a celebrated leader and Nobel Prize-winning peace activist. In the end, Alex reflects on her life, having carved her own path as an academic and a woman who made her own choices, even if dragoning was not one of them.

Through these intertwined personal and political narratives, When Women Were Dragons redefines family, freedom, and what it means for women to reclaim their power.

Characters

Alex Green

Alex Green is the protagonist and narrator of When Women Were Dragons, whose memoir forms the backbone of the novel. As a character, Alex is shaped by her silences, growing up in a society that represses and censors discussions about dragoning, a metaphor for women’s liberation.

Throughout the narrative, she is a deeply introspective and complex figure who struggles to reconcile her personal experiences with the larger societal expectations imposed upon her. From a young age, Alex learns to navigate a world where her questions go unanswered, and her identity is shaped by the absence of clear explanations, particularly around her mother’s illness and disappearance.

Her feelings of abandonment by both her parents—her mother due to cancer and dragoning, and her father due to his emotional distance and later remarriage—lead her to take on adult responsibilities prematurely. Alex is also marked by her intellectual curiosity, fostered in part by Mrs. Gyzinska, who encourages her to pursue higher education.

As the novel progresses, Alex’s journey becomes one of self-discovery and acceptance as she grapples with the significance of dragoning and her place within that narrative. Despite never dragoning herself, Alex’s narrative illustrates that transformation and liberation can take many forms, and she ultimately finds fulfillment in academia and personal relationships.

Bertha Green

Bertha, Alex’s mother, is an enigmatic figure whose illness and absence dominate Alex’s early life. A gifted mathematician, Bertha represents both the potential and the limitations imposed on women in mid-20th century America.

Her story is one of sacrifice, both in her career and personal life, as she gives up her academic pursuits to fulfill the traditional roles of wife and mother. Bertha’s transformation into a dragon is implied to be connected to these sacrifices and the societal pressures that stifle women’s ambitions.

Her eventual death from cancer parallels the repression of women’s desires and the destructive toll it takes on their bodies and spirits. Bertha’s silence and passivity stand in stark contrast to the liberation that dragoning offers, symbolizing the internal conflict between societal expectations and personal freedom.

Marla Green

Aunt Marla, Bertha’s sister, serves as a foil to Bertha, embodying nonconformity and independence. As an auto mechanic who wears slacks and defies traditional gender roles, Marla is a clear representation of a woman who has refused to be confined by societal expectations.

Her relationship with Alex is nurturing, and she plays a pivotal role in helping Alex understand her family history and the nature of dragoning. Marla’s own dragoning during the Mass Dragoning event reflects her deep-seated desire for freedom and her rejection of the constraints placed upon her as a woman.

She eventually returns in her dragon form to play a critical role in Beatrice’s upbringing, forming an unconventional family with her partner Edith and two other dragons. Marla’s character arc is one of empowerment and defiance, demonstrating the potential for women to create new lives and new family structures outside of societal norms.

Beatrice Green

Beatrice, Alex’s adopted sister and Marla’s biological daughter, represents a younger generation of women who are less bound by the taboos surrounding dragoning. From a young age, Beatrice is fascinated by dragons and displays signs of her impending transformation, such as her eyes changing and talons appearing.

Her character embodies the desire for liberation that dragoning symbolizes, and she ultimately embraces her dragon identity fully. Beatrice’s journey reflects a generational shift in attitudes toward dragoning, as society gradually becomes more accepting of women’s transformations.

Her eventual role as a dragon who contributes to world peace and wins a Nobel Peace Prize highlights the potential for dragons—and by extension, liberated women—to reshape society in positive ways. Beatrice’s character arc is one of empowerment and self-realization, as she grows into her true self and achieves great success.

Mr. Green

Alex and Beatrice’s father, Mr. Green, is a largely absent and emotionally distant figure who embodies the patriarchal values of mid-20th century America. He disapproves of education for women, believing that a woman’s role is to be a wife and mother.

After Bertha’s death, Mr. Green abandons his daughters, prioritizing his new wife and son, and leaving Alex and Beatrice to fend for themselves. His character represents the oppressive societal structures that the novel critiques, as he fails to understand or support the women in his life, instead opting for emotional detachment.

His role in the story underscores the emotional toll that patriarchal expectations place on both men and women, as his inability to connect with his daughters mirrors the broader societal inability to understand and accept the phenomenon of dragoning.

Mrs. Helen Gyzinska

Mrs. Gyzinska, a fierce librarian and member of the Wyvern Research Collective, plays a significant role in Alex’s life. She acts as a mentor and provides Alex with the intellectual tools to challenge societal norms.

Through her work with Dr. Gantz, Mrs. Gyzinska is dedicated to uncovering the truth about dragoning, fighting against the censorship and repression that surround the phenomenon. Her character is a symbol of resistance to patriarchal control, and she represents the power of knowledge and education in the fight for women’s liberation.

Mrs. Gyzinska’s guidance helps Alex to understand her own potential and the importance of pursuing her education, even in the face of her father’s disapproval. She also serves as a bridge between the hidden history of dragons and the new generation of women who are learning to embrace their power.

Dr. Henry Gantz

Dr. Gantz is a scholar who, alongside Mrs. Gyzinska, works to reveal the truth about dragoning. His character represents the intellectual pursuit of knowledge in the face of societal repression, as he dedicates his life to studying dragons and documenting their existence.

Dr. Gantz’s research provides the historical context for the novel’s speculative elements. His work is instrumental in helping Alex understand the broader implications of dragoning.

His character underscores the importance of challenging official narratives and seeking out suppressed truths, particularly when it comes to marginalized groups like women and dragons. Dr. Gantz’s relationship with Alex is one of mutual respect, as they both strive to uncover the truth and resist the forces that seek to keep it hidden.

Sonja Blomgren

Sonja is Alex’s long-lost romantic partner, and her reappearance toward the end of the novel marks a significant moment in Alex’s personal journey. Sonja represents a form of love and connection that Alex had lost due to the repressive forces in her life.

Her return allows Alex to explore a part of herself that she had kept hidden. Their relationship is a quiet but powerful testament to the possibility of personal liberation and the importance of choosing one’s own path, even in a world that seeks to limit women’s options.

Sonja’s presence in Alex’s life is a reminder of the personal connections that sustain us. She highlights the value of living authentically, even if that means defying societal expectations.

Themes

Societal Repression and the Obscuration of Female Identity and Agency

At the heart of When Women Were Dragons lies an exploration of societal repression, particularly how the patriarchal structures of Alex’s world control, obscure, and suppress female identity and agency.

The concept of “dragoning” serves as an allegory for self-liberation, capturing the potent struggle of women to break free from the narrow roles imposed upon them.

In the post-war, mid-century American setting of the novel, women like Alex’s mother Bertha and her aunt Marla are confined by rigid gender roles that dictate their value based on traditional domesticity—roles that value them only as wives, mothers, and caretakers.

Barnhill depicts a world that intentionally obscures knowledge of dragoning, much like how patriarchal societies historically erase or distort women’s experiences.

By using fragmented narratives and historical redactions, Barnhill illustrates how systemic censorship not only restricts the freedom of women but actively suppresses their transformative potential. The Mass Dragoning event of 1955, and the subsequent silencing of its truth, speaks to how societies suppress revolutions that could challenge entrenched gender dynamics.

Dragoning becomes a way for women to reclaim their agency, but it’s framed as dangerous, uncontrollable, and something to be feared—a projection of societal anxiety around women’s autonomy.

Memory, Trauma, and the Unreliability of Narration as Feminist Resistance

The novel’s use of an unreliable narrator, particularly through Alex’s fragmented recollections and her selective remembrances, reflects the complex relationship between trauma and memory. Alex’s personal narrative is filtered through the cultural repression of female experiences, which leads to a kind of self-censorship and internalized doubt.

In the same way that women are encouraged to forget or obscure their dragonings, Alex’s perspective is clouded by societal expectations and her own trauma from growing up in an oppressive environment.

This unreliable narration serves as a metaphor for how women’s histories are often pieced together in ways that fail to capture the full truth, distorted by the patriarchal lens that denies their autonomy.

The novel engages with the feminist critique of historical narratives by highlighting how memory is not merely subjective but often strategically shaped by power structures. The disjointed, evasive quality of Alex’s memoir represents an act of resistance—by remembering, she reclaims her story, even if that memory is hazy, incomplete, or painful.

In this way, the novel suggests that reclaiming memory, even an imperfect one, is a radical act of feminist resistance.

Transformation as a Mechanism for Empowerment and the Reclamation of Female Bodies

Dragoning, as a metaphor for transformation, becomes a powerful symbol for the reclamation of the female body and identity in the novel. The novel’s world teaches women to hate or fear their own bodies, reinforcing the idea that their transformations are monstrous or unnatural.

Barnhill’s depiction of the dragons, however, contrasts this view by showcasing the beauty, power, and freedom inherent in the transformation.

The physical metamorphosis into dragons not only grants these women the ability to fly and breathe fire but also serves as a larger metaphor for autonomy and self-possession.

It is through this transformation that women in the novel reclaim their bodies from a society that commodifies and controls them. Alex’s journey, even though she never physically dragons, is deeply tied to this theme.

She learns to embrace the possibility of transformation in others and eventually respects its significance in her sister Beatrice’s life, even though it may not be her own path.

By expanding on the transformative power of dragoning, Barnhill critiques the patriarchal control of female bodies, linking it to a broader feminist discourse about the right to bodily autonomy and self-determination.

The Intergenerational Transmission of Silence, Strength, and Subversive Knowledge

The novel intricately weaves together the experiences of multiple generations of women, emphasizing how silence and knowledge are passed down through familial and societal lines.

This intergenerational aspect, illustrated in the relationships between Alex, her mother, her aunt, and eventually Beatrice, captures the tension between enforced silence and the subversive transmission of strength and wisdom.

The phenomenon of dragoning, hidden from younger generations through social taboos, nonetheless finds its way into the consciousness of women like Alex and Beatrice through whispered stories, subtle clues, and repressed memories.

Barnhill explores how silence can be both a tool of oppression and a form of protection; women are forced to remain silent about their dragonings, but this silence also contains power, as it shields them from the punitive forces of a male-dominated society.

The women who transform and leave their lives behind do so not out of a desire for abandonment but as a radical assertion of their own power. This quiet transmission of strength is best embodied in Alex’s relationship with her aunt Marla, who serves as a link to the hidden history of women who have dragoned.

Through this generational connection, Barnhill critiques the erasure of female knowledge and celebrates the covert ways in which women preserve and pass on their legacy of resistance.

The Fluidity of Family, Community, and the Reconstruction of Social Roles

In When Women Were Dragons, Barnhill fundamentally challenges traditional conceptions of family, motherhood, and community. The post-dragoning world forces characters to reconfigure their understanding of what it means to belong, as traditional family units are shattered and new forms emerge.

The communal raising of Beatrice by Aunt Marla and her dragon companions underscores the novel’s assertion that family is not a static, biological entity but rather a dynamic, chosen structure built on mutual support and shared values.

The novel critiques the nuclear family model, where women are often confined to the roles of wife and mother, and instead posits a more fluid, collective approach to caregiving and familial bonds.

The transformation of women into dragons disrupts the patriarchal systems that define family in rigid, gendered terms.

In embracing these new definitions of family, characters like Alex and Beatrice demonstrate that the ties that bind are not restricted to blood or traditional roles but are shaped by shared experiences, love, and mutual respect.

This reimagining of social roles not only empowers the individual women who transform but also enables broader societal change, as dragons begin to take on leadership roles and enact policies that dismantle the old, oppressive systems.

Barnhill’s speculative world becomes a powerful commentary on the limitations of rigid social structures and highlights the necessity of imagining new ways of organizing society—ways that are inclusive of all forms of identity, expression, and transformation.