Who to Believe Summary, Characters and Themes

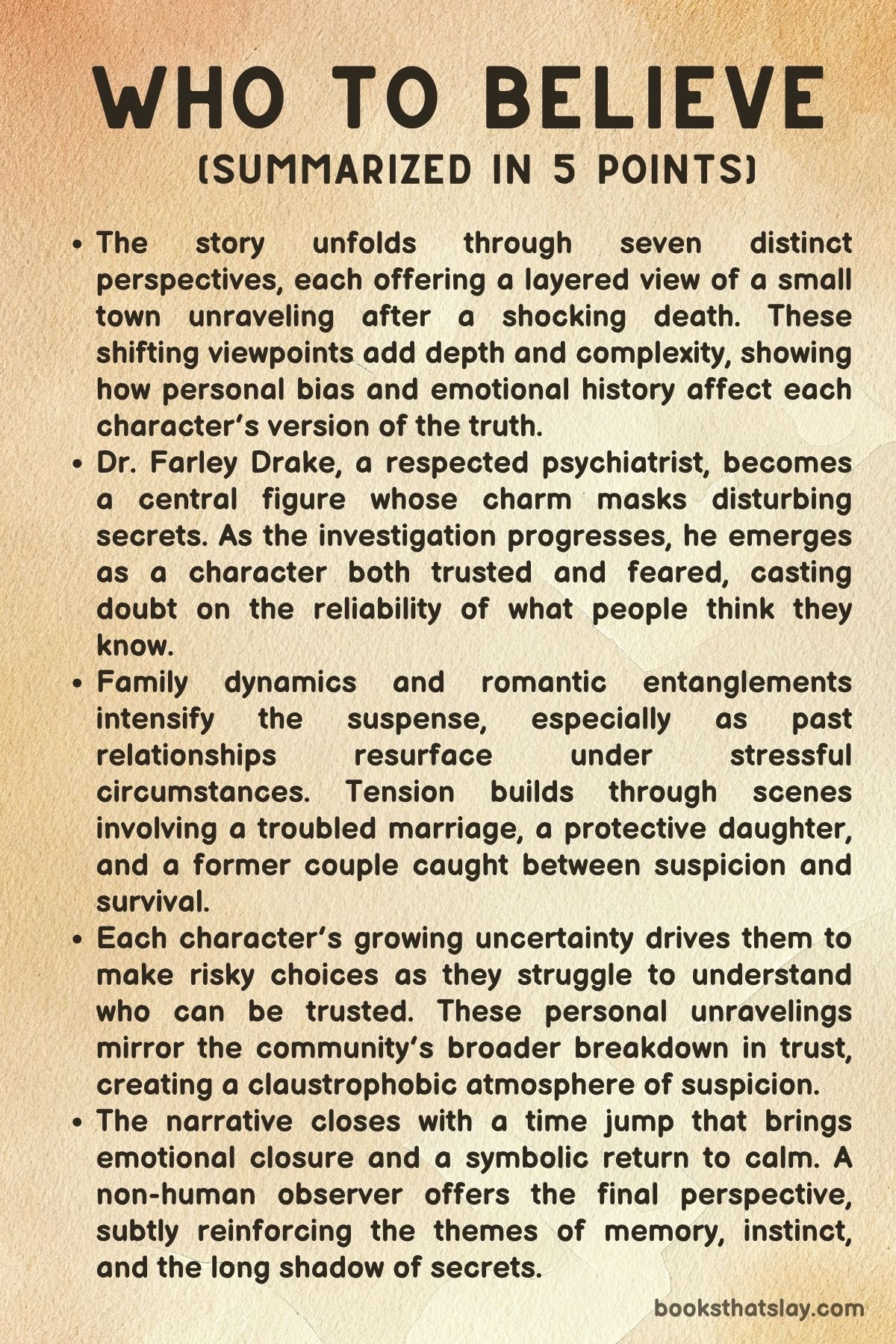

Who to Believe by Edwin Hill is a slow-burning psychological mystery that explores the dark entanglements of small-town life, where every relationship hides a shadow and every interaction threatens to unravel the truth. Set in a quiet coastal town in Massachusetts, the novel centers on Dr.

Farley Drake, a therapist whose calm, professional exterior conceals deep, dangerous impulses. With a murder investigation simmering in the background and a cast of interlinked characters—each burdened by secrets, betrayals, and buried crimes—the novel challenges the reader to question the reliability of memory, morality, and the people we choose to trust. It is a chilling, layered narrative of manipulation, voyeurism, and psychological decay.

Summary

In Who to Believe, the story begins in a small, tight-knit town where Dr. Farley Drake, a local psychiatrist, maintains a carefully cultivated façade of respectability.

Beneath this exterior, however, he harbors dangerous impulses and unethical habits. Farley is intimately entwined with his patients’ lives, frequently crossing professional boundaries and manipulating those around him to maintain control.

The novel opens with his therapy sessions with Alice Stone, a woman whose quiet intensity and buried fears hint at a traumatic past. Alice is increasingly anxious, and her fears escalate with the news of the recent murder of Laurel Thibodeau—a local woman who was bound and suffocated in her home.

This event sends shockwaves through the town, drawing suspicion and gossip, especially around Laurel’s husband, Simon, whose financial struggles and behavior cast him as a prime suspect.

Farley occupies a unique position, privy to confidential information that allows him to insert himself into the center of the investigation without technically participating. His connections to many of the town’s residents—Alice, Georgia Fitzhugh (a Unitarian minister and former patient), and Richard (Georgia’s estranged husband and Farley’s current partner)—position him as a seemingly neutral observer.

But he is far from neutral. His voyeuristic tendencies, emotional manipulation, and professional misconduct gradually expose him as not just unethical but dangerous.

The novel escalates during a birthday party hosted by Alice and her husband Damian, a charismatic documentarian. The gathering is full of strained interactions and unspoken tensions.

Alice and Damian’s marriage is fraying; Damian dominates the spotlight, while Alice hides behind politeness and growing resentment. Georgia struggles with the dual burdens of being a spiritual leader and a mother to Chloe, her volatile daughter.

Richard, caught between his past with Georgia and his complicated present with Farley, adds to the emotional chaos. Farley, ever observant and self-satisfied, feels confident in his ability to control the narrative.

However, Damian’s interest in true crime and suspicion about the murder begin to draw dangerous attention toward Farley, especially when Damian starts assembling evidence linking several local deaths—including Laurel’s—to Farley’s former patients.

As Farley realizes Damian may be on to him, he begins to unravel. He spies on Damian, sneaks into his office, and discovers a whiteboard covered in connections among victims—all tied to Farley.

He rationalizes his murders as necessary, as acts of cleansing or justice, convincing himself he’s in control. Alice discovers the whiteboard too and confronts Farley.

Though she fears what Damian might uncover, she doesn’t yet see Farley for what he is. Meanwhile, Farley begins to contemplate eliminating Richard to silence potential leaks.

He allows Alice to continue believing Damian might be the killer, subtly redirecting suspicion away from himself.

Alice, however, is not a passive character. Her own moral ambiguity is soon revealed—she too has a past marked by violence, having killed a priest in Maine and a predatory teacher in her youth.

Her relationship with Max, the police chief, adds another dimension of complexity. They share a brief moment of connection and attraction, but Alice remains emotionally evasive, caught between guilt, fear, and survival.

When she finds a burner phone possibly linked to Damian’s affair with Laurel, she hides it, unsure whether to protect herself, her husband, or the fragile truths everyone is avoiding. Her son Noah’s budding relationship with Chloe also introduces another volatile thread.

A phone shared between the teenagers sparks suspicion, drawing attention from both parents and police.

As the investigation deepens, Alice begins to grasp the full weight of the secrets around her. Her marriage deteriorates as Damian confesses to an affair with Laurel but denies involvement in her death.

He’s obsessed with solving the mystery, not realizing how close the killer truly is. In a cruel twist, Farley’s actions grow bolder.

During a beachside party, tensions explode. Georgia publicly berates Max, Farley behaves erratically, and Alice teeters on the edge of a breakdown.

Damian, still gathering evidence, finally admits to Ritchie—Georgia’s ex-husband and Farley’s partner—that he was with Laurel the night she died.

Ritchie becomes a key figure as his own secrets are exposed. Emotionally fragile and dependent on Farley, Ritchie begins to question the truth of their relationship.

When Farley disappears after sneaking out one night, and Chloe also vanishes, Ritchie panics. Soon, detectives arrive with shocking news: Farley is dead, and suspicion immediately shifts to Ritchie.

His phone contains a damning text inviting someone to meet Farley at the spot where he died—sent during the night Farley was killed. Though the text came from Ritchie’s phone, there’s a possibility Chloe sent it using his passcode.

Nevertheless, Ritchie is arrested, caught in a storm of evidence, betrayal, and spiraling consequences.

As Ritchie’s life falls apart, Georgia’s own descent accelerates. Flashbacks reveal her manipulation of events through the anonymous burner phone.

She used it to nudge Damian into suspecting a serial killer with links to Farley, hoping to plant the narrative that would shield her own crimes. Georgia is the one who killed Laurel, enraged after Laurel threatened to expose her.

She later lured Damian to his death after he discovered the burner phone and began piecing together her lies. Her final confrontation with Damian ends with her running him off the road and killing him.

But Chloe, unknowingly holding the burner phone, eventually gives it to Max.

In the novel’s final sequence, Georgia is emotionally undone. Her daughter Chloe, having seen too much, reports her to the police, ending the cycle of secrets with a final act of moral clarity.

Three months later, a coda from the perspective of Harper, the family dog, offers a surprising resolution: it was Alice who killed Farley in self-defense after he attacked her on the marsh. Harper witnessed everything, her loyalty contrasting the duplicity of the humans around her.

In the end, Max and Alice find tentative peace, Chloe begins to heal, and Georgia fades into the shadows of her own moral ruin. Who to Believe leaves readers questioning every truth, every motive, and every version of reality, as it closes on a town forever changed by the lies it once kept hidden.

Characters

Dr. Farley Drake

Dr. Farley Drake is the dark heart of Who to Believe, a man whose dual identity as a trusted therapist and secret killer reflects the novel’s central exploration of hidden truths and moral ambiguity.

On the surface, Farley is a respected psychiatrist in a small Massachusetts town, granted intimate access to his patients’ inner lives and entrusted with their deepest fears. But beneath this professional facade lies a calculating and dangerous figure who weaponizes psychological insight for his own manipulative ends.

Farley’s voyeuristic compulsion to observe others—whether by prying into private conversations or profiling the townspeople during social gatherings—feeds his inflated sense of control. His romantic relationship with Ritchie, initiated during a period of therapeutic overreach, exemplifies his ongoing boundary violations.

Farley convinces himself that his actions are justifiable, even noble, yet he is responsible for the calculated murders of his own clients, believing he remains invisible behind the mask of professionalism. He sees himself as both savior and judge, a man who decides who is beyond redemption and must be eliminated.

Ultimately, his desire to manipulate those around him leads to his downfall—murdered not in cold blood but in a desperate act of self-preservation by Alice Stone, the one woman who sees him for what he truly is. Farley’s descent from therapist to predator is not sudden, but insidious, revealing how easily power can curdle into abuse when veiled by moral superiority.

Alice Stone

Alice Stone emerges as a complex, enigmatic figure whose emotional fragility masks a deep capacity for both violence and reinvention. At the start of Who to Believe, Alice appears to be a woman on the edge—haunted by anxiety, distrustful of her husband Damian, and dependent on therapy.

Yet her layers slowly unravel, revealing a history of violent acts, including two previous murders committed under morally gray circumstances. Alice is not a passive victim but a woman shaped by trauma, secrecy, and emotional contradictions.

Her relationship with Farley is marked by psychological gamesmanship, while her bond with Damian deteriorates under the weight of infidelity and suspicion. At times, Alice appears desperate for clarity, even seeking solace in a brief romantic moment with Max, the police chief.

But she is also fiercely strategic—she hides evidence, withholds truths, and navigates dangerous relationships with a calculated awareness of how perception can shift blame. Alice becomes a reluctant investigator and an unreliable narrator, caught between her desire for truth and her instinct for survival.

When she kills Farley in self-defense, it is less an eruption of violence than an act of liberation. Her evolution throughout the novel—from vulnerable patient to morally conflicted avenger—encapsulates the story’s exploration of duality and the dark instincts that often lie beneath polished exteriors.

Damian Stone

Damian Stone, Alice’s husband, is a man driven by ego, ambition, and a compulsive need to document and control narratives. As a filmmaker, Damian positions himself as an observer, but his deep involvement in the town’s secrets renders him an active participant in its unraveling.

His charisma masks a self-centered nature; he thrives on attention and uses his charm to manipulate those around him. Damian’s obsession with uncovering the identity of a serial killer is not purely motivated by justice or truth—it’s also about career reinvention and personal redemption.

Ironically, he is oblivious to the danger seated right beside him, as Farley, the man he suspects the least, is the very killer he hunts. Damian’s past infidelity with Laurel Thibodeau, his arrogance in assuming narrative control, and his dismissive treatment of Alice paint him as a man constantly escaping accountability.

His eventual confessions—first to Ritchie, then indirectly through his investigations—reveal a man grasping for control as his world implodes. When he finally confronts Georgia, he unwittingly seals his fate, becoming her second victim.

Damian’s death is the culmination of his blind trust in his own intellect and the fatal underestimation of those closest to him.

Ritchie Macomber

Ritchie Macomber is a man burdened by emotional dependency, secrecy, and a lifetime of playing second fiddle—to Georgia, to Farley, and even to his daughter Chloe. Once married to Georgia, Ritchie finds temporary comfort in his relationship with Farley, but that too becomes a trap.

Farley controls every aspect of his life—from what he eats to how he behaves—rendering Ritchie a prisoner in a gilded cage. Despite this, Ritchie clings to Farley for validation, a symptom of his deeper fears of abandonment and worthlessness.

His relationship with Chloe is strained by guilt and confusion, especially as he suspects she may be involved in something sinister. Ritchie’s lies, both to others and himself, catch up with him as the police close in.

Wrongfully accused of Farley and Damian’s murders, he becomes the fall guy in a story teeming with better liars and more ruthless players. His arrest marks the collapse of the fragile persona he tried to maintain—a decent father, a caring partner, a misunderstood man.

Instead, Ritchie becomes collateral damage in a town where love is conditional, and survival depends on deception.

Georgia Fitzhugh (Georgia George)

Georgia Fitzhugh, also known as Georgia George, is perhaps the most tragic and chilling character in Who to Believe. As the town’s Unitarian minister, Georgia embodies moral authority and spiritual guidance, but beneath this persona lies a deeply fractured woman driven by jealousy, betrayal, and a hunger for control.

Her resentment toward Ritchie for leaving her for Farley festers into a slow-burning rage. Her interactions with Alice and Damian, initially grounded in friendship, become manipulative as she uses her access and knowledge to orchestrate chaos.

Georgia’s descent begins with emotional betrayal and culminates in murder—not once, but twice. Her killing of Laurel, motivated by a mix of jealousy and fear of exposure, reveals the extent to which she is willing to go to preserve her crumbling image.

Her later murder of Damian, a cold and calculated act, underscores her transformation into someone who no longer sees moral lines. Yet, Georgia is not without moments of remorse.

Her final breakdown, catalyzed by Chloe’s discovery of her guilt, shows a woman whose soul has been hollowed by her own choices. Georgia is a study in moral corrosion, where spiritual authority becomes a mask for rage, vengeance, and emotional decay.

Max (Chief of Police)

Max, the town’s police chief, represents the uneasy balance between duty and personal entanglement. Though he initially seems like a peripheral figure, Max’s presence becomes increasingly significant as the narrative unfolds.

He is torn between his responsibilities as an investigator and his complicated feelings for Alice and Georgia, both of whom he has been romantically involved with. Max is observant and methodical, yet emotionally compromised.

His growing suspicions are tempered by a desire to believe in the people he once trusted. When Alice confesses pieces of her truth and Georgia becomes a person of interest, Max must choose between personal loyalty and professional integrity.

In the end, it is Max who begins to piece the mystery together, driven not by ambition or ego but by a quiet sense of justice. He is a steady presence in a storm of duplicity, and though flawed, Max offers a glimpse of moral clarity in a town otherwise corrupted by secrets.

Chloe Macomber

Chloe Macomber, the teenage daughter of Georgia and Ritchie, is a volatile and emotionally complex character caught in the crossfire of adult chaos. Her behavioral issues—aggression, social alienation, and impulsivity—stem from a household defined by instability and betrayal.

Chloe’s entanglement with Noah Stone and her unspoken awareness of the town’s secrets make her a silent observer with dangerous knowledge. Her discovery of the burner phone, her witnessing of Georgia’s attempted attack on Damian, and her eventual role in turning her mother in all contribute to her emergence as a moral compass in the story.

Chloe is deeply wounded, yet she matures through the trauma. Her decision to report Georgia to the police, despite the personal cost, marks her transition from a reactive adolescent to a young woman capable of ethical clarity.

Chloe, in the end, becomes the unwitting agent of justice—an embodiment of the new generation determined not to repeat the sins of their elders.

Harper (the Dog)

Harper, the family dog, offers an unusual but poignant perspective in the final chapter of Who to Believe. Her simple, loyal worldview contrasts sharply with the human deceit and emotional turbulence that dominate the novel.

Through Harper’s recollections, the truth about Farley’s death is quietly confirmed—Alice killed him in self-defense, a fact that no human character fully discloses. Harper becomes a vessel for narrative closure, her perspective grounding the story in instinct and loyalty rather than manipulation and fear.

While not central to the plot’s action, Harper’s presence offers thematic resonance. In a novel obsessed with duplicity and betrayal, the dog’s unwavering love and unfiltered perception serve as a gentle counterpoint, suggesting that truth, though obscured, always leaves a trace.

Themes

Duality of Identity and Hidden Selves

In Who to Believe, nearly every character harbors a carefully concealed second identity that governs their private actions while presenting a palatable, even virtuous, exterior to the community. Farley Drake embodies this theme most starkly, as he appears to be a responsible, insightful therapist while secretly orchestrating a string of calculated murders.

His profession, which revolves around penetrating facades and healing trauma, ironically becomes a cover for his voyeurism, manipulation, and violence. His boundary-crossing behavior—socializing with patients, romantically entangling himself with clients’ spouses, and surveilling the people in his life—illustrates how deeply his two identities are intertwined.

He rationalizes his actions through a distorted moral lens, believing his insights grant him dominion over others’ lives.

Alice Stone, too, leads a double life. Her public persona is one of a cautious, victimized wife seeking therapy and navigating a crumbling marriage.

Yet her past includes her own acts of violence, revealing a complicated and darker personal history. Her identity becomes even more fragmented as she oscillates between passive observer and active participant in the novel’s unfolding violence.

Similarly, Georgia George, the minister, uses her position of spiritual authority as a mask for personal vengeance. Her descent from moral guide to manipulative murderer illustrates how the roles people play in public can starkly contrast with their inner motives and suppressed rage.

This theme underscores the psychological tension running through the novel—what people hide, and how easily they can slip into roles that allow them to commit morally unconscionable acts. Each character’s double life is not a sudden transformation but a gradual unraveling, often rationalized in the name of justice, self-preservation, or love.

As each truth is exposed, the cost of maintaining those dualities becomes fatal.

Manipulation, Power, and Control

Control operates as a driving force in the interactions between characters, whether through psychological dominance, emotional blackmail, or calculated deception. Farley exerts dominance over others by exploiting their vulnerabilities under the guise of therapeutic care.

His relationship with Ritchie is defined by micro-control—dictating his food choices, appearance, and social behavior. It’s not enough for Farley to be loved; he must orchestrate the conditions of that love and ensure he remains the central axis of Ritchie’s world.

His power is psychological, and he believes it justifies any measure of coercion, including murder.

Georgia uses manipulation differently, operating through subtle influence and indirect threats. Her anonymous texts to Damian plant the idea of a serial killer, nudging him toward a false narrative she can exploit.

Her spiritual role becomes a cover for behavior that is as coldly strategic as it is desperate. When Laurel threatens to expose her, Georgia commits murder not in a fit of rage but with clinical precision.

She then frames Farley by planting evidence, showing how far she’s willing to go to retain the illusion of righteousness and control the emerging story.

Even Alice participates in these dynamics, using selective confession, passive-aggressive language, and strategic concealment to maneuver through suspicion. Her decision to hide the burner phone and withhold information from Max is not just about fear; it’s about preserving the upper hand in a situation where trust is scarce and secrets are currency.

Control in the novel isn’t only about overt dominance—it’s about narrative ownership. Each character strives to shape the story others believe, fearing that if they lose that grip, their lives will unravel.

The novel thus becomes a contest of psychological warfare, with power wielded not through brute force but through calculated manipulation and emotional coercion.

Moral Ambiguity and Justified Violence

The boundaries between right and wrong are profoundly destabilized in Who to Believe, where murder becomes not a shocking exception but an almost logical response to betrayal, exposure, or emotional desperation. Farley, a serial killer, doesn’t see himself as evil.

He sees his killings as necessary acts—eliminating emotional burdens, silencing threats, or exacting a twisted form of justice. He weaponizes his medical knowledge and social intelligence to rationalize his actions, creating a chilling portrait of a man who believes himself to be both judge and redeemer.

Alice represents a different shade of moral ambiguity. Her past includes at least two murders, both committed under circumstances that could be framed as self-defense or retribution.

Yet she’s not haunted by guilt in a traditional sense—she fears being caught more than she regrets her actions. She spends much of the narrative shifting blame, avoiding accountability, and manipulating others’ perceptions of events.

Her final act of killing Farley—arguably the most justifiable of all—still fits into a pattern of evasiveness and quiet cunning rather than a clear moral reckoning.

Georgia’s descent into criminality is fueled by personal betrayal and a crumbling identity. Her crime is calculated and indirect: she murders Laurel to protect her secret manipulations and later kills Damian to preserve the narrative she constructed.

Her justifications stem from emotional injury, resentment, and a need to feel powerful in a life where she has otherwise been discarded. The novel doesn’t offer easy moral judgments—each character acts from a place of personal grievance and psychological fracture, making their actions understandable, if not excusable.

By blurring the lines between victim and perpetrator, the story suggests that morality is often compromised not by grand evil but by the cumulative weight of fear, desire, and ego. The novel invites the reader to question how much of their sympathy is shaped by appearances and how easy it is to cross a moral boundary when the stakes feel personally justified.

The Destructiveness of Secrets

Secrets in this novel aren’t passive—they are toxic agents that actively corrode relationships, identities, and communities. From the start, the town is shown to be held together by a fragile web of gossip, half-truths, and hidden pasts.

Farley’s life is constructed on layers of secrecy: his professional ethics are a front for predatory behavior, and each of his murders is an attempt to protect one secret by creating another. Yet the more he hides, the more exposed he becomes, leading to his ultimate demise.

Alice’s secrets are equally volatile. Her concealed murders, her knowledge of Damian’s affairs, and her manipulation of Max all contribute to a steadily growing sense of paranoia.

She becomes both a keeper of secrets and a threat to those hiding them. Her decision to suppress the existence of the burner phone and her willingness to let others believe false narratives illustrate how silence becomes its own form of violence.

Georgia’s trajectory shows how a single secret can metastasize. Her anonymous manipulation through the burner phone starts as an act of petty vengeance but spirals into multiple murders.

Her secret communications, rooted in resentment and grief, become the catalyst for a cascade of events that destroy multiple lives. When her daughter Chloe begins to uncover the truth, Georgia realizes that secrecy has not protected her but isolated her irreparably.

The novel suggests that secrets demand constant maintenance—they need lies, manipulation, and increasingly desperate actions to keep them buried. But eventually, they surface, often at the worst possible time, implicating not just the keeper but everyone within their radius.

In this way, secrecy becomes a communal contagion, leaving no one untouched.

Fragmented Family and Emotional Inheritance

Family in Who to Believe is marked by dysfunction, emotional misalignment, and an inability to reconcile love with personal truth. Farley’s romance with Ritchie is layered with imbalance—Ritchie seeks validation and stability, while Farley exerts suffocating control.

Their relationship is not built on mutual respect but on psychological leverage. Ritchie’s emotional inheritance from his past—his insecurities, suppressed desires, and need for approval—makes him susceptible to Farley’s domination and contributes to the volatile outcome of their bond.

Georgia’s family is fractured not just by divorce but by emotional abandonment. Chloe’s behavioral issues stem from instability, and her mother’s secrecy and emotional withholding create a sense of alienation.

Chloe’s increasing independence becomes a threat to Georgia, who fears losing both control and the illusion of maternal influence. Chloe’s eventual decision to turn Georgia in is the most profound act of generational rupture, where a child breaks the cycle of deception at great personal cost.

Alice’s family is equally strained. Her marriage to Damian is eroded by betrayal, buried resentments, and conflicting ambitions.

Their son Noah becomes collateral damage, navigating a household brimming with tension and half-spoken accusations. His connection to Chloe adds another layer, suggesting that the younger generation is silently absorbing the traumas of their parents.

These emotional inheritances manifest in behavior, choices, and a constant proximity to danger.

The novel does not depict family as a source of comfort but as a landscape of disappointment, secrecy, and misplaced loyalties. What binds these families together is not trust or love but mutual concealment and unspoken trauma.

Emotional inheritance in this context becomes a burden rather than a bond, passed down through silence, manipulation, and acts of betrayal. In the end, the only path to healing appears to lie in rupture—when someone, often the youngest, decides to break the chain.