Why We’re Polarized Summary and Analysis

Why We’re Polarized by Ezra Klein is an incisive and layered examination of how the United States arrived at its current state of extreme political division. With the precision of a journalist and the breadth of a political theorist, Klein explores how identity, institutional structures, media incentives, and psychological predispositions have aligned to create a deeply polarized political environment.

Rather than framing polarization as a failure of civility or a byproduct of fringe ideologies, Klein contends that polarization is systemic and self-reinforcing—baked into the political and cultural machinery of contemporary America. He argues that this division is not only entrenched, but rational, rewarding, and even desirable for many of the actors involved. The book doesn’t just diagnose the problem; it also considers paths forward, urging a reconsideration of democratic structures, media habits, and personal political awareness.

Summary

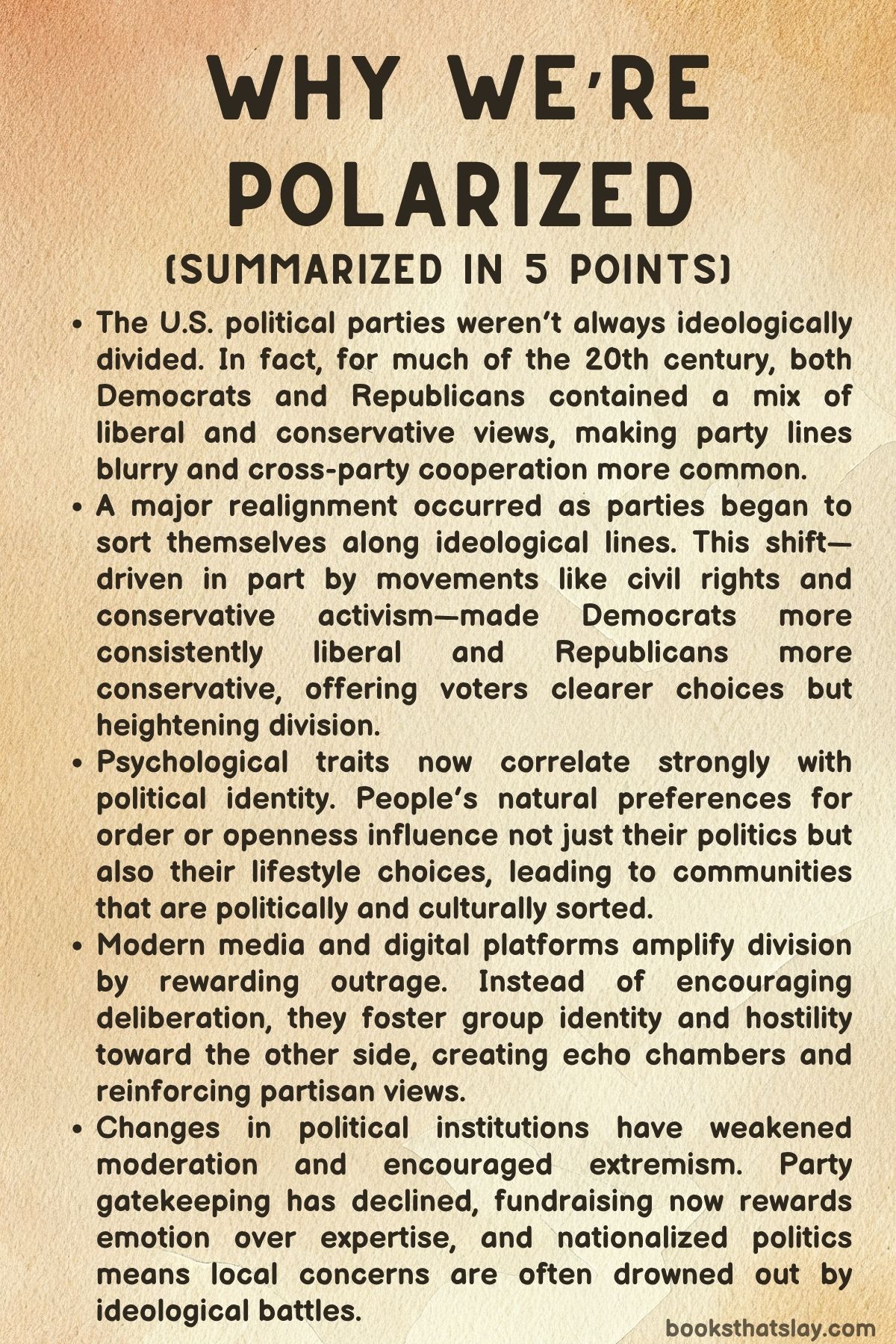

Why We’re Polarized opens with a historical reflection, demonstrating that today’s ideological divide between Democrats and Republicans is not a longstanding feature of American political life. In fact, until the mid-20th century, both parties contained a broad range of ideological positions.

Liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats were common, which often made party allegiance a poor predictor of political views. It was only in the second half of the 20th century—particularly after the Civil Rights Movement and the Goldwater revolution—that ideological sorting began in earnest.

This sorting, where conservatives gravitated to the Republican Party and liberals to the Democratic Party, laid the foundation for today’s polarized environment.

One of the book’s central claims is that political identity has evolved from a mere preference into a core part of personal identity. Party affiliation now encompasses views on race, religion, geography, culture, and even consumer habits.

As Americans have increasingly aligned their political views with their cultural identities, they’ve also become more hostile toward those in the opposing camp. The term “negative partisanship” captures this well: people are often more motivated by their disdain for the other party than by loyalty to their own.

This trend explains why self-identified independents often vote as predictably as strong partisans—they may not feel attached to their own party, but they are committed to opposing the other.

Klein uses insights from psychology and behavioral science to show that this is not irrational. People derive meaning, safety, and validation from their group identities.

Traits like openness to experience or conscientiousness are strongly predictive of liberal or conservative leanings. Similarly, worldviews—whether one sees the world as dangerous and fixed, or safe and fluid—strongly correlate with political preferences.

The result is not simply ideological disagreement, but the formation of “mega-identities” that consolidate race, religion, class, and culture under partisan labels. Once identities are aligned in this way, compromise becomes harder and persuasion becomes almost impossible, because disagreement is no longer about policy—it’s about self.

The transformation of media plays a significant role in reinforcing these identities. Social media platforms, which are designed to maximize engagement, reward outrage, conflict, and simplicity over nuance and empathy.

Algorithms elevate emotionally charged content, often favoring partisan or extreme views. Journalists, in turn, have adapted their practices to these incentives.

Opinion journalism has evolved into identity journalism, where content is designed not to persuade or inform, but to affirm the worldview of a target audience. This shift has made Americans more informed and more partisan—but not more understanding.

Exposure to opposing views often has the opposite of its intended effect. Klein references empirical studies showing that when people are exposed to counterarguments or opposing political messages, they don’t soften their views but become more entrenched.

This backfire effect stems from the deep-seated nature of political identity. When political beliefs are entwined with personal worth and social belonging, disagreement feels like a threat.

As a result, political debate becomes less about facts or policy and more about demonstrating loyalty to one’s group.

The collapse of localism in American politics further deepens polarization. There was a time when political identity was filtered through local or state issues.

Legislators were expected to represent their districts, not just their parties. But as media has nationalized and parties have become ideologically consistent, voters increasingly consume political news through a national lens.

They vote not based on local needs but on national party identity. This shift weakens the incentives for politicians to cooperate across the aisle and undermines the transactional politics that once made bipartisan deal-making possible.

The structure of American political institutions compounds the problem. The filibuster, gerrymandering, and the Electoral College are not neutral tools—they now serve to entrench minority rule and discourage compromise.

For example, tight margins in the Senate or House make it advantageous for the minority party to obstruct governance entirely, betting on voter frustration to swing future elections. This creates a permanent campaign atmosphere in which governing becomes secondary to political positioning.

While both parties have become more ideologically consistent, Klein argues that polarization is asymmetric. The Republican Party has moved further right than the Democrats have moved left, and it has increasingly embraced anti-democratic behavior.

The party’s reliance on a demographically narrow base—predominantly white, older, and Christian—has made it more vulnerable to conspiratorial thinking and racial grievance politics. Donald Trump didn’t invent this dynamic, but he capitalized on it more effectively than any of his predecessors.

His dominance of the GOP demonstrates how political systems without strong party gatekeeping can empower demagogues who appeal to the most energized segments of the electorate.

Klein also examines how campaign financing contributes to the problem. Small-donor fundraising, enabled by digital platforms, tends to reward candidates who generate strong emotional reactions—whether positive or negative.

This shifts power away from institutional donors, who often have moderating incentives, and toward ideological purists and provocateurs. As a result, the most attention-grabbing politicians tend to rise, regardless of their capacity to govern.

The book concludes by offering potential solutions. Klein divides reform into three categories: bombproofing, democratizing, and balancing.

Bombproofing involves removing political flashpoints—such as the debt ceiling—that invite partisan brinkmanship. Democratizing includes reforms like ranked-choice voting and proportional representation, which could weaken the two-party stranglehold and reward coalition-building.

Balancing requires structural changes to offset demographic imbalances in representation, such as granting statehood to Washington, D. C., and Puerto Rico.

On a personal level, Klein encourages readers to examine their own political behavior and media consumption. Rather than immersing in national narratives, he advocates a return to local and state-level political engagement, where ideological boundaries are often less rigid and impact is more immediate.

He challenges readers to think critically about how they form opinions, where they get their news, and whether their political identity is helping or hurting their civic engagement.

In sum, Why We’re Polarized is not just a chronicle of American dysfunction. It’s a rigorous analysis of how well-intentioned developments—ideological clarity, participatory media, democratic reforms—have combined to create a political culture in which division is the default and consensus is elusive.

Klein’s message is clear: if we don’t understand the forces behind polarization, we can’t begin to undo it.

Key People

Ezra Klein (Narrator and Analyst)

As the central voice of Why We’re Polarized, Ezra Klein functions not merely as an author but as an intellectual guide, weaving together political theory, social psychology, and historical analysis to diagnose the roots and consequences of polarization in the United States. He is both an observer and interpreter, framing his narrative with the precision of a journalist and the critical depth of a political theorist.

Klein’s character is defined by his earnest desire to unravel complex systemic issues and present them in accessible yet intellectually rigorous terms. Rather than adopting a detached or neutral posture, he is acutely aware of his own positionality—acknowledging the limitations of institutional journalism, the biases of identity, and the flaws in the democratic process.

This self-reflective quality makes his voice compelling; he doesn’t claim omniscience but builds his authority by synthesizing expert research across disciplines. Throughout the book, he remains focused on diagnosis rather than partisan advocacy, though he is not afraid to call out asymmetries in the political system, particularly the Republican Party’s drift toward extremism.

Klein’s narrative is deeply humanistic, grounded in a belief that understanding how people form their political identities—through emotion, tribalism, and cognitive bias—is essential to reversing polarization. His character is not just that of a commentator but of a concerned citizen and reform-minded thinker.

Barry Goldwater

Though not a central character in terms of narrative presence, Barry Goldwater looms large in the book’s historical argument as a pivotal ideological figure. Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign, despite ending in electoral defeat, represents a turning point in American political development—marking the ideological hardening of the Republican Party.

His demand for ideological clarity over pragmatic coalition politics introduced a more doctrinaire and confrontational style of conservatism, which gradually reshaped the GOP from a big-tent party to a more ideologically consistent and exclusionary one. Goldwater, as portrayed in Why We’re Polarized, is both a symbol and a catalyst: his campaign crystallized the transformation of conservatism from a regional tendency into a national movement and paved the way for the rise of modern conservative media and infrastructure.

He is portrayed as a man of conviction whose embrace of polarization as a political strategy had long-term ramifications far beyond his own political career. His influence endures in the form of party sorting and the realignment of voter identities that underpin current political divides.

Donald Trump

Donald Trump appears in the narrative as the embodiment of the forces that Klein argues have reshaped—and in many ways, destabilized—American democracy. Trump is not framed merely as an aberration or an outsider but as a culmination of deeper systemic trends: media sensationalism, identity-driven politics, and the weakening of party institutions.

He is characterized by his intuitive mastery of outrage politics, his ability to dominate the media landscape, and his appeal to tribal identity over policy nuance. In Klein’s analysis, Trump’s rise is not surprising but disturbingly logical within the context of an electoral system that rewards charisma, conflict, and emotional mobilization.

Trump is a figure of amplification: he intensifies identity politics, exploits partisan media, and erodes democratic norms not by revolution but by doubling down on the incentives that already exist. His character, as rendered in the book, is less about ideology than about performance—a political actor who mirrors the dysfunctions of the system and thrives precisely because of them.

Through Trump, Klein explores the dangers of de-democratization, the erosion of truth, and the vulnerability of democratic institutions in a hyperpolarized society.

The American Voter

Arguably the most complex and multifaceted character in Why We’re Polarized is the American voter. Rather than treating voters as rational actors choosing among policy options, Klein delves into their psychological and emotional dimensions.

The voter in this narrative is shaped by identity, tribal loyalty, fear, and social reinforcement. Klein challenges the classical model of democratic citizenship by showing how group identity—rooted in race, religion, geography, and personality—dictates political behavior far more than ideology or informed reasoning.

The American voter is both subject and agent of polarization, susceptible to “motivated reasoning” and prone to viewing politics as an extension of selfhood. Voters consume partisan media, sort themselves into ideologically homogeneous communities, and interpret facts through tribal filters.

Yet they are also victims of a system that rewards division, punishes moderation, and diminishes the role of local politics. In Klein’s portrayal, the voter is neither wholly responsible nor entirely innocent—a product of evolutionary wiring and institutional design whose behavior is predictable yet deeply consequential.

This character study is both empathetic and sobering, underscoring the need for structural reforms that can redirect voter incentives and reduce the emotional intensity of political life.

The Political Media Ecosystem

Though not a person, the media ecosystem functions as a quasi-character throughout the book—dynamic, manipulative, and increasingly omnipotent. It is not a monolith but a collection of shifting incentives, personalities, and platforms that together shape the contours of public discourse.

Klein renders the media as a feedback machine that thrives on outrage and tribal affirmation, turning news into a form of emotional entertainment. The media does not just report on polarization; it actively deepens it by highlighting conflict, rewarding ideological purity, and crowding out nuance.

The evolution from opinion journalism to identity journalism is presented as a critical transformation in how citizens engage with political information. This “character” is one of the most insidious in the book—subtle, ever-present, and difficult to reform—because it mirrors the incentives of the political system itself.

It is also highly asymmetric: conservative media outlets like Fox News and talk radio play a unique role in the epistemic isolation of Republican voters, creating what Klein calls a “tribal epistemology. ” As a result, the media landscape functions less as a neutral arbiter of truth and more as a battleground where loyalty and identity supersede evidence.

The Democratic and Republican Parties

Both major political parties in the United States are treated not just as institutions but as evolving characters whose internal dynamics, histories, and voter coalitions have radically transformed over the past century. The Republican Party is characterized by its ideological purification, structural advantages, and increasing resistance to democratic norms.

Klein presents it as the more radicalized of the two, shaped by demographic anxiety, right-wing media, and an electoral system that allows it to retain power without majority support. It is portrayed as a party more willing to obstruct, bend norms, and embrace identity politics.

In contrast, the Democratic Party is characterized by its coalition-based pragmatism, internal ideological diversity, and structural disadvantages. Klein depicts the Democrats as a party stretched thin by the demands of multiracial, multireligious, and geographically dispersed constituencies.

While not immune to polarization, they are less able to act in lockstep and more bound by institutional constraints. These contrasting party “characters” underscore one of the book’s central insights: polarization is asymmetric, and any attempt to understand it must acknowledge the different incentives and behaviors of the two sides.

In sum, the character landscape of Why We’re Polarized is richly populated not only by historical and political figures but by institutions, voters, and systems rendered with psychological and structural depth. Through these character portraits, Klein brings clarity to the emotional, ideological, and institutional forces that have reshaped American democracy.

Analysis of Themes

Ideological Sorting and the Collapse of Cross-Party Coalitions

The realignment of political parties into ideologically coherent blocs has resulted in a dramatic transformation of the American political landscape. In earlier decades, Democrats and Republicans were ideologically mixed, with conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans coexisting within their respective coalitions.

This fluidity enabled bipartisan cooperation, legislative compromise, and political discourse that wasn’t predetermined by party identity. Over time, this cross-cutting structure dissolved, replaced by a hardened ideological sorting.

Political identities are now more clearly aligned with ideological beliefs, making party membership a proxy for one’s entire worldview. This reconfiguration has not only redefined electoral behavior—voters now overwhelmingly select candidates along strict party lines—but also reshaped legislative dynamics.

Bills that once garnered bipartisan support now face unified partisan opposition, even when policy content overlaps with historical precedent. As seen with the contrast between bipartisan support for Medicare in the 1960s and the total Republican rejection of the Affordable Care Act, ideological clarity has replaced legislative pragmatism.

This has also enhanced the effectiveness of negative partisanship, where individuals are more motivated by opposition to the other party than by loyalty to their own. The psychological shift from pragmatic evaluation of candidates to identity-based voting has made American politics more stable in terms of voter predictability but less functional in terms of governance.

Identity-Driven Partisanship and Psychological Sorting

The rise of identity politics has created a political environment where individual psychological traits play a central role in determining party affiliation. Traits like openness to experience and conscientiousness are not only predictive of lifestyle choices but also map closely onto liberal and conservative ideologies, respectively.

This psychological alignment with party identity has led to the creation of what the author terms “mega-identities”—political identities that encompass race, religion, region, education level, and even consumer behavior. Politics, therefore, has become less about rational policy debates and more about emotional expression of in-group loyalty and out-group hostility.

The phenomenon is amplified by tribal psychology: minimal group theory experiments have shown how readily humans form discriminatory loyalties based on arbitrary differences. In politics, these tribal tendencies are no longer latent; they have been activated and institutionalized.

As partisan identities stack atop other social identities, disagreement over policies morphs into existential confrontation. Even exposure to opposing viewpoints no longer fosters empathy or compromise.

Instead, it triggers defensive reactions that reinforce preexisting beliefs. The psychological mechanisms of motivated reasoning and confirmation bias entrench individuals within self-validating belief systems.

As a result, political polarization today is less about differing views on taxes or healthcare and more about competing realities shaped by the psychological imperative to belong and to protect one’s identity group.

Media Incentives and the Outrage Economy

The structural transformation of media—from print and broadcast journalism to an algorithm-driven digital landscape—has drastically altered the incentive structure of political communication. Attention is the currency of modern media, and nothing captures attention more effectively than outrage.

Social media platforms amplify emotionally charged content, privileging outrage and conflict over nuance and analysis. Journalists and media outlets, responding to audience incentives, have evolved from purveyors of information to affirmers of group identity.

Opinion journalism has given way to identity journalism, in which news is tailored to confirm the biases of partisan audiences rather than challenge them. This has not only fragmented the information ecosystem but also intensified polarization by reinforcing tribal narratives.

Exposure to cross-cutting content no longer moderates perspectives; instead, it hardens them. Algorithms that prioritize engagement over accuracy further compound the problem by creating echo chambers where dissenting voices are filtered out.

Media coverage has thus become reactive, shaped by virality and controversy rather than civic responsibility. Politicians like Donald Trump exploit this dynamic expertly, using media coverage as a vehicle for identity signaling and base mobilization.

The result is a political discourse dominated by spectacle and outrage, with substantive policy debate relegated to the margins. The media’s complicity in this process underscores the collapse of traditional gatekeeping mechanisms and the rise of a polarized attention economy.

Structural Incentives and Institutional Dysfunction

The design of American political institutions, once intended to encourage compromise and coalition-building, has increasingly become a source of dysfunction under conditions of polarization. Tight electoral margins have transformed legislative incentives: rather than cooperating to govern, minority parties now obstruct in order to reclaim power.

The filibuster, once rarely used, has become a routine instrument of sabotage. Tools like the debt ceiling, previously administrative in nature, are now leveraged for partisan brinkmanship with severe national consequences.

These procedural mechanisms have been weaponized in a context where governing is no longer the principal goal. Simultaneously, reforms intended to democratize the political process—such as open primaries and small-donor fundraising—have produced unintended consequences.

Candidates are no longer filtered by party elites but by highly motivated partisan voters, often leading to the nomination of ideologically extreme figures. Small donors, driven by emotional investment rather than policy knowledge, reward those who generate outrage, further skewing the political center.

Meanwhile, nationalized political identities have eroded the relevance of local governance, making it harder for politicians to prioritize constituent needs over party loyalty. Together, these factors contribute to gridlock, disincentivize compromise, and empower demagogues.

The institutional scaffolding that once supported American democracy now strains under the weight of incentives misaligned with effective governance.

Asymmetric Polarization and Republican Radicalization

While both major parties have experienced shifts in ideology and structure, the transformation of the Republican Party has been especially dramatic. No longer a coalition of moderate conservatives and traditionalists, the GOP has moved toward a more radical, grievance-based politics that questions democratic norms and relies heavily on a homogeneous base.

This shift has been aided by structural advantages such as the Senate, Electoral College, and gerrymandering, which allow Republicans to win and govern without majority support. The party has embraced obstruction as a strategic norm, rejected the legitimacy of opposing viewpoints, and increasingly traffics in conspiracy theories and disinformation.

The right-wing media ecosystem reinforces this radicalism by creating an epistemic environment where truth is determined by partisan loyalty rather than evidence. This dynamic contrasts with the Democratic Party, which, though polarized, is constrained by a more diverse and geographically dispersed coalition.

Democrats must cater to a broader range of identities and ideologies, which necessitates some level of compromise and institutional respect. The asymmetry in coalition structure explains why Republican extremism often goes unmatched on the left and why institutional reforms aimed at restoring balance are so difficult to implement.

The GOP’s radicalization represents not just a political shift but a challenge to the democratic norms that undergird the entire system.

Reimagining Political Engagement and Democratic Renewal

In the face of rising polarization and institutional decay, the author offers a roadmap for both systemic and individual-level renewal. At the systemic level, structural reforms are essential to safeguard democracy.

These include eliminating the debt ceiling, reforming or abolishing the filibuster, instituting ranked-choice voting, expanding voting access, and granting statehood to underrepresented territories. These proposals aim to reduce the anti-majoritarian tilt of American institutions and make them more responsive to the electorate.

However, reform alone is insufficient. Individuals must also audit their own political behavior.

This means engaging with local politics, where ideological divisions are often less entrenched and civic participation can yield tangible results. It also involves rethinking media consumption habits, resisting the pull of outrage-driven content, and seeking out diverse perspectives.

By decoupling political identity from social identity and focusing on actionable civic participation, citizens can resist the forces of polarization. The call is not for a return to centrism, but for a more thoughtful, grounded engagement with politics—one that prioritizes local realities over national narratives, dialogue over performative conflict, and democratic health over partisan victory.

The vision is one of resilience: a democracy that can withstand ideological division because it is built on institutions and civic habits designed for pluralism and mutual respect.