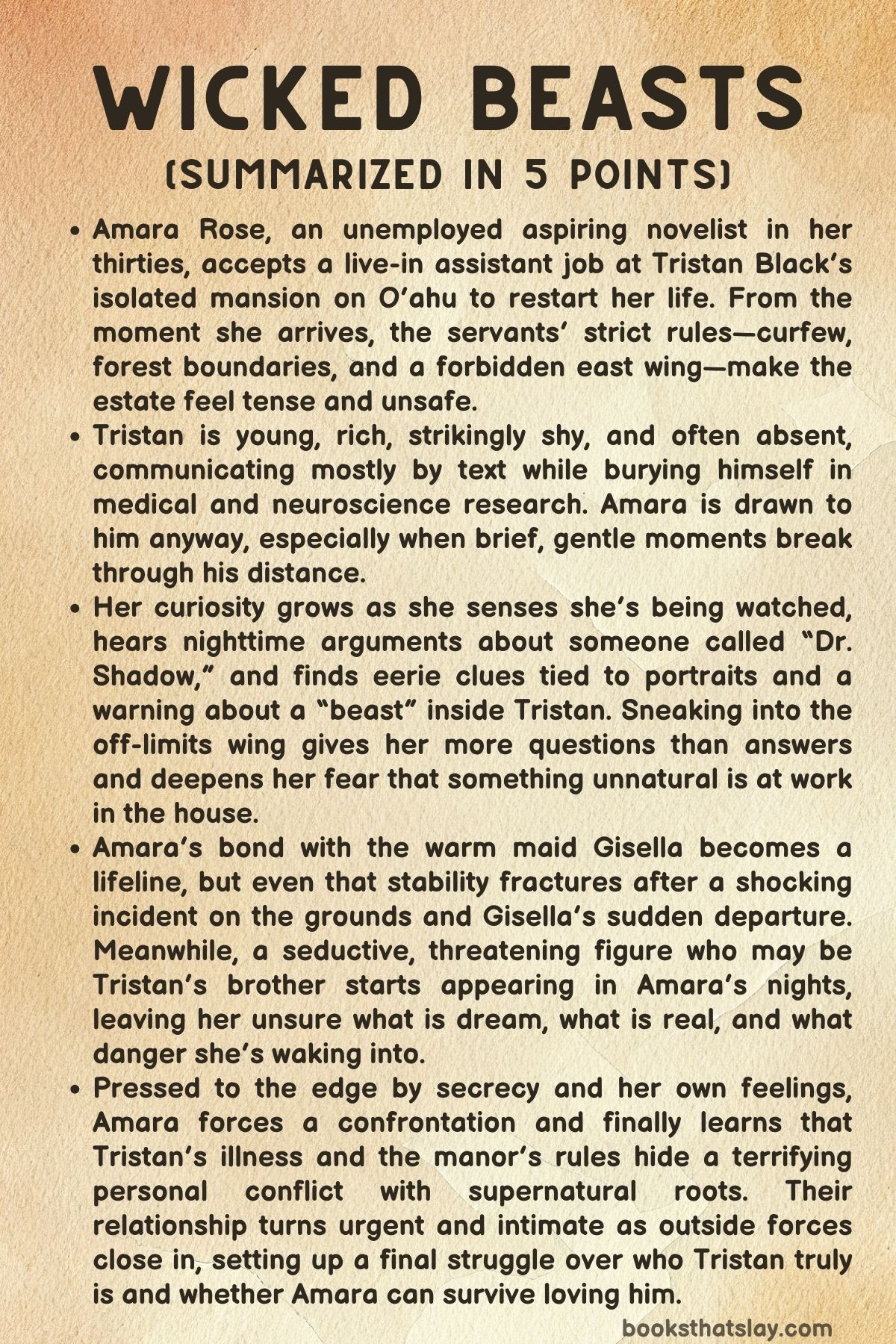

Wicked Beasts Summary, Characters and Themes

Wicked Beasts by Shelley Leigh Crane is a gothic-leaning paranormal romance set on O’ahu, where the quiet beauty of the island contrasts with a mansion full of secrets. The story follows Amara Rose, a struggling novelist who takes a live-in assistant job for the reclusive heir, Tristan Black.

What seems like a fresh start quickly turns strange: rigid house rules, a forbidden east wing, nightmares that feel like memories, and whispers about a dangerous presence called Dr. Shadow. As Amara’s attraction to Tristan deepens, she’s pulled into a supernatural family curse that blurs the line between desire, fear, and survival.

Summary

Amara Rose, an unemployed aspiring novelist in her thirties, accepts a live-in personal assistant position at Black Manor on O’ahu, hoping to escape her father’s house and a stalled life. Her friend Kehau drives her to the secluded estate, where the scale of the property and the surrounding forest instantly unsettle her.

She is greeted by Mortimer, Tristan Black’s formal, unnervingly pale butler, who establishes strict rules: a curfew, no wandering from the gravel paths, and absolute prohibition from entering the east wing. Mortimer’s warning that Tristan “isn’t well” hangs in the air.

Mrs. Wong, the stern housekeeper, reinforces the boundary with veiled menace, while Gisella, a kind young maid, explains the rules more gently and hints that the groundskeeper Manu is harsh and dangerous when crossed.

Amara meets Tristan briefly on the staircase. He is a handsome, muscular twenty-eight-year-old who appears shy to the point of awkwardness.

He notices the rose she carries, has a vase brought for it, and retreats toward the forbidden wing. Amara feels an immediate pull toward him but tries to remain professional.

Her first nights in the manor are filled with eerie silence and vivid dreams about Tristan that leave her embarrassed and unsure whether her mind is racing or the house is affecting her. She senses being watched, hears footsteps outside doors, and wakes with the lingering feel of someone else’s presence.

Amara begins her duties through Tristan’s texts rather than face-to-face instructions. His study is packed with medical and science books, and he asks her to gather biochemistry volumes and sort his email.

One message about a PET scan alarms her, suggesting his “project” is not merely academic. When Amara drifts too close to the east-wing door, Mrs.

Wong physically pulls her away, reminding her that curiosity is unsafe here. Amara overhears staff arguing about her, including fearful references to “Dr.

Shadow,” a person they cannot protect her from. The name lodges in her mind.

Despite Tristan’s absence, Amara finds herself drawn to him. When they finally talk, he explains he is researching how hormones influence mood and behavior, and he invites her to call him Tristan.

Their warmth appears real, but it can vanish without warning; during dinner he shifts from gentle attention to cold distance, leaving her confused. Her unease grows into obsession with the east wing.

One night she sneaks there, finding an unlocked portrait room that contains paintings of Tristan, including one of him younger and slightly decayed. Beneath it is an inscription calling him a “beast.” The lamp goes out suddenly, and she flees, shaken.

Her connection with Tristan builds in uneven steps. He suggests a walk on the grounds, and during it Amara lets herself admit her fascination and concern for how hard he works.

When she twists her ankle, Tristan carries her to her room and tends to her with a tenderness that feels intimate.

Yet afterward he retreats again, returning to distant texts and avoidance.

Meanwhile Amara learns from Gisella that Dr. Shadow is Dante, Tristan’s older brother, who visits at night and is the reason for curfew.

The household’s fear makes more sense, but it also deepens the mystery.

Amara’s isolation intensifies when Dr. Shadow appears in her room late at night.

He is confident, seductive, and threatening, speaking as if he owns the house and her attention.

He flirts with danger, gives her whiskey, and hints that her safety is fragile.

Tristan dismisses Amara’s report of this meeting, insisting Dante is not there and implying she dreamed it.

The denial feels like betrayal.

Nightmares then grow stranger: Amara dreams of Dr. Shadow entering her room, taking her forcefully, and calling Tristan into the encounter.

She wakes alone, unsettled by how real it felt.

The manor turns darker.

Mrs. Wong and Mortimer confront Amara about a private letter she once stole from the library and hid. Before the confrontation finishes, Gisella screams after seeing a bloodied man on the lawn.

The body vanishes later, and staff offer flimsy explanations, increasing Amara’s suspicion. She finally reads the stolen letter: written by a woman named Cordelia, it claims she altered Tristan through magic in revenge, tying a “beast” inside him forever and promising he will never be free.

Manu later retrieves the letter with eerie certainty, warning Amara that Cordelia’s love was witchcraft and that Amara is in danger.

Soon after, Gisella leaves the manor, unable to endure the terror, and Amara is left alone with the rules and the silence.

Cordelia herself appears to Amara in the woods, beautiful and unsettling, seemingly a ghost who knows Amara’s thoughts.

She taunts Amara about falling for Tristan and dares her to ask about the past.

Cuts on Amara’s feet and a trampled trail outside her window suggest the encounter was not a dream. When Amara presses Tristan, he finally brings her into the east wing.

The room is a hidden medical study, and he admits the “project” is about himself: strange scans and symptoms he cannot cure.

He confesses he likes Amara but has kept distance because Dr.

Shadow “takes everything” from him. Amara refuses to be treated as something to guard or surrender, and their argument breaks into honesty.

Tristan asks for one selfish day with her, and she says yes. They spend hours together, finally giving in to their feelings.

After their night, Tristan believes Shadow will harm Amara and decides to end his own life to stop the cycle.

He prepares chemical restraints and attempts to sedate and cool his body to block Shadow’s control, finally forcing himself into a freezing plunge tub.

Amara finds him unconscious and nearly dead.

A strange doctor, Wollstonecraft, arrives and takes Tristan away without explanation.

Days pass in stunned waiting. Amara confronts Mortimer, who admits he staged the bloody lawn incident to test emergency response time, fearing Tristan would attempt suicide.

He reveals the truth: Tristan and Dante are the same person, split into two selves in one body. Cordelia, a former girlfriend who favored the reckless Shadow side, cursed Tristan through her own death, sealing the division and feeding the darker self.

Cordelia’s ghost attacks Amara in the manor, and Manu forces Amara to leave for her father’s house, saying the ghost cannot kill Tristan directly but can kill Amara. Even away, Cordelia finds her, compelling Amara into a trance that draws her back to Black Manor and into a hidden cellar.

There Cordelia uses a shard of an ornate mirror to stab Amara, attempting to remove her from Tristan’s life. Amara slips into a surreal near-death state, watching the scene from outside herself.

Tristan arrives, burns Amara’s rose necklace and mirror shards—Cordelia’s tools—and an inhuman scream signals the ghost’s suffering. Tristan saves Amara, but gains a deep facial scar in the battle, proof the curse still has teeth.

Amara wakes a week later in the manor, alive but weak, with Tristan beside her. He explains that destroying Cordelia’s objects lessened her grip but did not erase Shadow.

Shadow surfaces less often now and seems strangely aligned with Dr. Wollstonecraft’s experiments.

As Amara recovers, she and Tristan rebuild their closeness, holding to the fragile hope that love can anchor him. Finally, Amara uncovers the portrait in the east wing and finds it changed to a more beastlike Tristan marked by the scar.

A blue butterfly drifts in, candles go out, and footsteps approach. Dr. Shadow’s voice calls her “Miss Rose,” and he steps into the room, reminding Amara—and Tristan—that the struggle for his soul is not over.

Characters

Amara Rose

Amara Rose is the story’s emotional lens and the character through whom the reader experiences both the seduction and the dread of Black Manor. In her thirties and stuck in a painful loop of unemployment and dependence on her father, she arrives on O’ahu carrying equal parts desperation and hope, and that mix shapes nearly every choice she makes.

Her identity as an aspiring novelist matters: she is trained to notice details, to read subtext, and to chase narrative threads, so the mansion’s rules and silences don’t just frustrate her, they provoke her. Amara’s curiosity is not idle nosiness; it’s tied to her hunger for agency.

Yet her curiosity is also the doorway that danger walks through. She is drawn to Tristan’s quiet vulnerability and the heat she feels around him, and her attraction steadily erodes her promise to remain “professional.” What makes Amara compelling is that she is brave and frightened at the same time—she pushes into the east wing, confronts Tristan, and keeps asking for truth even while her body and dreams betray how overwhelmed she is. Her arc is a movement from displacement and self-doubt into fierce self-assertion: she refuses to be treated as a pawn between Tristan and Dr.

Shadow, calls out Tristan’s protective paternalism, and survives Cordelia’s supernatural violence without surrendering her will. By the end, Amara is no longer a guest being managed by the manor; she becomes an active participant in its haunted, dangerous reality, choosing love without romantic blindness and insisting on her own right to the truth.

Tristan Black

Tristan Black appears first as the classic secluded master of the house—wealthy, elegant, lonely—but the story quickly reframes him as a man at war with himself. Tristan’s outward personality is soft-spoken, awkwardly shy, and almost painfully controlled.

He is kind in small, telling ways—his attention to Amara’s rose, his gentle care when she is injured, his insistence on consent even within her dreamscape—and these moments reveal a core decency. At the same time, Tristan’s distance and sudden coldness show how terrified he is of what he carries inside.

His “research project” is a disguise for his attempt to rationalize and cure his own condition, suggesting a mind that depends on science and discipline to survive emotional chaos. Tristan’s tragedy is that he believes love is dangerous to the people he wants most; he withdraws from Amara not because he doesn’t feel deeply, but because he does.

The curse fracturing him into Tristan and Dr. Shadow makes his life a constant calculation of risk, shame, and self-loathing, and his suicidal plan in the east wing is the clearest proof of how exhausted he is by the battle.

Yet Tristan is not merely a victim. He chooses restraint, chooses tenderness, chooses to fight for Amara after losing control.

His scar and the altered portrait at the end show a man who has not been freed from monstrosity but has integrated it into his identity. Tristan’s character lives in the tension between gentleness and threat, and his love story with Amara is really a struggle to believe he deserves to exist as more than a curse.

Dr. Shadow

Dr. Shadow, later revealed as Dante and ultimately as Tristan’s darker half, is the embodiment of predatory charisma and unfiltered impulse.

He moves through the manor like a rumor turned into flesh—nighttime footsteps, whispered arguments, rules built around his presence. Where Tristan is hesitant and conscientious, Shadow is bold, theatrical, and cruelly honest about desire.

His sexuality is framed as dangerous because it ignores boundaries unless they are imposed, and his language repeatedly targets Amara’s fear and fascination, turning both into weapons.

Yet Shadow is not a separate villain in a simple sense; he is the part of Tristan that was rejected, indulged by Cordelia, and then cursed into permanence.

That makes him simultaneously a threat to Amara and a revelation of Tristan’s buried self. Shadow’s taunting dominance, his tendency to “take everything,” and his relish in power all point to a psyche built on resentment—resentment at restraint, at rejection, at being treated as the half that must be locked away.

Still, even Shadow is bound by the same emotional circuitry that governs the curse; he cannot fully destroy Tristan without destroying himself, and later he appears aligned with Dr. Wollstonecraft, hinting at a shift from pure sabotage toward survival.

Shadow functions as the novel’s living shadow-side of love: he is attraction without safety, truth without mercy, and freedom without conscience.

Mortimer

Mortimer is the manor’s architectural spine: formal, watchful, and quietly decisive. At first he seems like a classic forbidding butler who enforces rules for the master’s comfort, but his role grows into something more complex—guardian, strategist, and reluctant manipulator.

Mortimer’s gentility masks a relentless pragmatism. He believes safety requires control, and he treats Amara as both someone to protect and someone whose curiosity could rupture a fragile equilibrium.

His staged violence in the garden reveals the depth of his loyalty to Tristan and the lengths he will go to anticipate catastrophe, even if it means traumatizing others. Mortimer also serves as the keeper of truth, feeding Amara pieces only when she corners him, which suggests a man who has lived too long with extraordinary horror to risk honesty lightly.

Under his polished exterior is grief and responsibility: he is steward to a broken heir, witness to Cordelia’s curse, and perhaps the last person who still believes Tristan can be saved. Mortimer’s morality is therefore gray but purposeful—he lies, he withholds, he orchestrates, not out of malice, but because he sees disaster coming faster than anyone else does.

Mrs. Wong

Mrs. Wong is the strict, unbending counterweight to Amara’s curiosity and to Mortimer’s measured diplomacy.

She is defined by hard boundaries: the east wing is forbidden, the curfew is non-negotiable, and outsiders are inherently suspect. Her sternness reads like hostility early on, yet it is rooted in fear and a fierce protective instinct for Tristan and the household.

Mrs. Wong understands the manor’s danger in a way Amara does not, and the severity of her reactions—dragging Amara away from doors, interrogating her about the letter, warning her about letting darkness into her bed—shows someone who has watched the curse ruin lives repeatedly.

She is also a moral realist: she doesn’t romanticize Tristan’s struggle, and she explicitly ties Amara’s choices to harmful consequences for him. Unlike Mortimer, who gambles with strategy, Mrs. Wong wants containment above all else. That makes her appear cold, but it also makes her one of the only characters consistently focused on survival rather than desire or hope.

She represents the household’s collective trauma and the instinct to lock pain away before it devours someone else.

Gisella

Gisella begins as warmth in a cold house—a friendly young maid who laughs, shares rules softly, and makes Amara feel less alone. Her kindness is not naïve; it’s a coping strategy against a place that erodes certainty.

Gisella’s own losses—her dead boyfriend and parents—shape her into someone fragile but generous, and her grief creates a bond with Amara that feels like sisterhood. When she collapses after seeing the bloodied body, her reaction is a reminder that the manor doesn’t only threaten physically, it retraumatizes emotionally.

Gisella also functions as a bridge to truth: she names Dante as Tristan’s brother and confirms the family’s strangeness long before Amara gets full answers. Her departure is quiet but devastating, showing how the manor drives away even those who try to survive it with lightness.

Gisella’s role in the narrative is to model what happens when sensitivity meets sustained horror: eventually the soul refuses to stay.

Manu

Manu is the manor’s earthy, intimidating sentinel, a man who seems carved out of the island itself—burly, blunt, and deeply aware of the dangers beyond the gravel paths. His hostility toward Amara is partly gatekeeping, partly instinctive protection: he sees her as both vulnerable and reckless.

Manu’s knowledge goes far beyond maintenance or gardening; he recognizes Cordelia, understands witchcraft, and moves through the supernatural landscape like someone who has fought it before. His almost magical moments—knowing where the letter is, lighting a candle without a visible flame—suggest he is not just a worker but a kind of ward or guardian with his own power.

Manu’s defining trait is protective severity. He stops Amara from following Tristan into the woods, drives Cordelia away when she attacks, and ultimately forces Amara to leave to save her life.

Yet he is not gentle about protection; he uses fear as a tool because he believes fear keeps people alive. Manu represents the practical side of resisting evil: not romantic, not polite, but committed.

Cordelia

Cordelia is the story’s curse given a face, voice, and history. Even before her ghost appears, she haunts the manor through the letter signed “C,” through portraits, and through the very structure of Tristan’s divided self.

As Tristan’s former lover, Cordelia is defined by obsession that masquerades as devotion. Her love is weaponized—described as witchcraft rooted in love and hate—and her suicide is both vengeance and binding spell, ensuring Tristan can never fully escape her influence.

As a ghost, Cordelia becomes a force of jealous possession, furious that Amara interrupts Tristan’s death and determined to eliminate her rival. She is manipulative and theatrical, using trance-like dances, mirrors, and symbolic objects to control or harm.

Yet Cordelia is not a flat monster; her existence reveals the novel’s darker thesis about love: that it can be a cage, that desire can refuse consent, and that grief can curdle into domination. Cordelia’s continued presence at the end—implied by the altered portrait, the butterflies, and the return of Shadow—suggests curses don’t vanish just because one tool is burned.

She is the lingering consequence of love twisted into ownership.

Dr. Wollstonecraft

Dr. Wollstonecraft arrives like a clinical contradiction to the manor’s gothic atmosphere: a strange doctor with experimental methods and an unsettling calm.

He functions as the boundary between science and the supernatural, a man willing to treat what seems untreatable.

His quick removal of Tristan after the suicide attempt implies both authority and secrecy; he is trusted by Mortimer and Mrs.

Wong despite being outside their household, which indicates a long-standing relationship with Tristan’s condition.

Wollstonecraft’s alliance with Dr. Shadow later on hints that his interest is not only in saving Tristan’s gentler half but in stabilizing the whole fractured person.

He is a figure of ambiguous hope—possibly miraculous, possibly morally flexible—representing the idea that even cursed bodies may be approached with method, experimentation, and risk.

Kehau

Kehau is Amara’s anchor to ordinary life and one of the few voices not warped by the manor’s ecosystem.

As the friend who drives her to Black Manor and listens to early worries, Kehau represents community, sanity, and the outside world’s logic.

She doesn’t have a large on-page role, but her presence is important because Amara keeps returning to her in thought and confession, using her as a mirror for what “normal” caution might look like. Kehau’s limited access to the manor’s secrets also highlights how isolated Amara becomes once she accepts the live-in job.

Ikaika

Ikaika appears primarily in the social world beyond the manor, and his outdoor event offers Amara a breathing space from claustrophobic fear. He is friendly, public, and surrounded by attention, which contrasts sharply with Tristan’s hidden life and Shadow’s nocturnal predation.

Ikaika’s role is less about deep personal arc and more about structure: he reminds both Amara and the reader that there is a vibrant, living Hawaii outside the estate, and his presence helps show how strangely the manor distorts Amara’s priorities. By leaving her alone at the event, even unintentionally, he also becomes the moment where Shadow’s gaze intrudes into the open world, proving there is no clean boundary between outside safety and inside danger.

Amara’s Father

Amara’s father stands as the symbol of the life she is trying to outgrow—bright, ordinary, and suffocating in its safety. He is not portrayed as cruel, but as a place of stalled adulthood for Amara, which is why returning to him feels like exile rather than rescue.

His eventual visit to the manor and reassurance that she is safe are bitterly ironic, underlining how powerless normal authority is against the supernatural stakes Amara has entered.

He represents the cost of Amara’s independence: choosing the manor means choosing a world her old life cannot understand or protect her from.

Themes

Isolation, confinement, and the haunted geography of the manor

From the moment Amara arrives at Tristan Black’s estate in Wicked Beasts, the setting is not just a backdrop but an active force shaping behavior.

The mansion’s size, the off-limits east wing, curfews, and the prohibition against leaving gravel paths create a lived experience of confinement.

Amara’s relocation to O’ahu is meant to be a fresh start, yet the job places her inside a carefully controlled environment where movement, knowledge, and even sleep are policed by other people. This turns isolation into something layered: she is physically removed from friends and normal social rhythms, but she is also isolated by the household’s refusal to answer questions.

The rules do more than keep her safe; they continuously remind her that she is an outsider who must accept boundaries she didn’t choose. The staff’s watchfulness and coded warnings (“he isn’t well,” “stay away from the east wing”) push her into a state of constant anticipation, making silence feel like a threat.

The manor therefore becomes a map of secrecy: certain doors are locked, certain hallways are dark, and certain truths are structurally unreachable. Even her bedroom is not fully hers, as dreams, night visits, and surveillance blur the line between private and invaded space.

This theme expands as Amara loses Gisella — the one person who helps her feel less alone. Gisella’s departure strips away emotional shelter and leaves Amara in numb routine, showing how isolation can hollow out identity over time.

The forest surrounding the house reinforces this feeling: it is close enough to tempt curiosity but fenced off by fear and by Manu’s force. The property’s geography teaches Amara to associate knowledge with danger and obedience with survival.

In that way, isolation is both a condition imposed on her and a tool used to manage the violent instability at the center of the household. The theme matters because it explains why Amara’s curiosity becomes almost compulsive.

When a person is trapped in a world built on partial truths, seeking answers starts to feel like the only way to breathe.

Dual identity, self-war, and the cost of repressing darkness

Tristan and Dr. Shadow embody a conflict that is psychological, moral, and bodily.

The story treats their split not as a neat good-versus-evil division but as a brutal cohabitation inside one life. Tristan is presented as shy, disciplined, and socially awkward, someone who tries to order his existence through science, routine, and restraint.

Dr. Shadow, by contrast, is confident, predatory, and openly sensual, acting without regard for consequence.

What makes this theme powerful in Wicked Beasts is that neither side can be dismissed as unreal; both have agency, memory, and appetite. Tristan’s research into hormones and brain activity is a concrete attempt to name and control what he experiences internally.

His failure to find a cure shows that knowledge is not always mastery, and that the self can contain forces that do not answer to reason.

The curse that ties the split to love and hate suggests that the fracture is fueled by emotion as much as biology, meaning that repression alone cannot solve it.

Tristan’s effort to become “better” in the eyes of academia and society is framed as noble, yet it also leaves him brittle and exhausted, and it gives Dr. Shadow more room to erupt.

The narrative implies that ignoring one’s darker impulses does not erase them; it concentrates them.

When Tristan tries to end his life to protect Amara, he is also trying to end the war within himself, showing how unbearable constant internal conflict can become.

The duality theme also challenges Amara’s perceptions. She is attracted to Tristan’s gentleness, but her dreams, fear, and later real encounters expose her to Shadow’s intensity.

This forces her to face her own divided reactions: longing and disgust, safety and danger, love and alarm. The inscription in the portrait room — insisting the “beast” exists within — functions as an external mirror of Tristan’s internal truth.

The altered portrait at the end, showing a more beastlike Tristan even after Cordelia’s tools are destroyed, underlines that the conflict is not neatly resolved. The darkness is reduced, redirected, maybe even negotiated, but it remains part of the self.

Through this, the book argues that identity is not always singular or stable, and that the most painful battles are often fought inside the boundaries of one body and one name.

Desire, consent, and the unstable line between fantasy and violation

Sexual tension in Wicked Beasts is never merely romantic decoration; it is a risky territory where agency, fear, and longing collide. Amara’s erotic dreams about Tristan begin almost immediately, and they are described as vivid and bodily convincing.

These dreams blur into the manor’s atmosphere of surveillance and secrecy, turning desire into something that can feel involuntary. When Dr.

Shadow appears in her room and the encounter takes place, the narrative later reveals it as a dream — but the impact on Amara is real: physical soreness, emotional confusion, and shame. This creates a theme around how fantasy can shape a person’s sense of self even when no physical act occurred.

At the same time, Dr. Shadow’s behavior is consistently framed in predatory language and coercive energy.

He enters her space without invitation, dominates the interaction, and speaks with threats disguised as seduction. Even if a scene is later labeled a dream, it still reflects a psychological invasion rooted in Amara’s fear of him and her uncontrolled attraction to what he represents.

The novel repeatedly tests consent in subtle ways: Tristan asks permission before touching her in the dream, contrasting with Shadow’s force; the household restricts Amara “for her safety” without her consent; Cordelia compels Amara into trance and movement without her will.

These parallels suggest that loss of control can happen through sexuality, care, or magic, and that the emotional aftermath is similar.

Amara’s growing intimacy with Tristan after he finally tells the truth is built on mutual desire and a moment of chosen vulnerability. Yet even this tenderness is threatened by Shadow’s claim that he “takes everything,” showing how a person can want love while fearing that desire itself will be used against them.

The theme is therefore not about condemning desire but about showing its volatility when power is unequal or when boundaries are uncertain.

Amara’s arc moves from passive embarrassment about her fantasies to active confrontation of what she wants and what she refuses.

The book treats her desire as human and complex, not a weakness to be punished.

But it also insists that desire without clear consent turns into terror.

In that way, the novel asks the reader to sit with discomfort: attraction to danger, the way fear can imitate excitement, and the necessity of claiming one’s own body and choices even in a world designed to steal them.

Obsession, curse-love, and how trauma reproduces itself

Cordelia’s curse is the narrative engine that turns personal history into present danger. Her letter reveals love that has curdled into possession, and revenge that is inseparable from longing.

She declares that she changed Tristan “in revenge” for what he did to her, but also insists that magic is rooted in love and hate, which makes the curse an extension of her emotional fixation rather than a separate act. The theme here is that obsession does not end with death; it mutates.

Cordelia’s suicide is not framed as release but as escalation, a final act that chains Tristan to her narrative forever.

Her return as a ghost shows trauma refusing to stay in the past.

She cannot kill Tristan directly, but she can stalk, threaten, and attempt to murder Amara, which suggests that obsession often lashes out at substitutes when it cannot reach its true target.

The curse also infects the household.

Mortimer, Mrs. Wong, and Manu build their lives around containing its consequences, normalizing secrecy, staged violence, and constant vigilance.

Trauma becomes institutional: rules, curfews, and locked doors are the physical manifestation of a long-running wound.

Amara steps into this system without knowing its origin, and her ignorance makes her vulnerable to repeating the same patterns — secrecy, coercion, and fear.

Gisella’s breakdown after seeing the “body” links her old grief to new horror, showing how trauma echoes across different lives.

Even Tristan’s split identity can be read through this lens: the curse forces a violent internal division that mirrors Cordelia’s divided emotions.

The phantom’s ability to lure Amara into trance and to reenact her killing in a vision suggests that trauma is not just memory but experience replayed, imposed, and witnessed again.

When Tristan burns the mirror shards and the rose necklace, he tries to cut the loop, but the lingering split and his scar mark the limits of escape.

Trauma leaves residue, even after the immediate threat is attacked. This theme is not a simple “love gone wrong” warning.

It is a study of how possession hides inside declarations of devotion, how revenge can be a distorted plea for connection, and how people caught in another person’s obsession lose years of their own life managing the fallout.

The manor’s current dangers are therefore not random supernatural events; they are the aftershocks of a relationship that refused to accept endings.

Autonomy versus protection, and the violence of withheld truth

Amara’s experience in Wicked Beasts is shaped by a constant tug-of-war between others deciding what is “best” for her and her own need to choose.

The staff repeatedly justify rules as safety measures, but they do so without explanation or partnership.

Mortimer’s insistence on curfew, Mrs. Wong’s harsh physical removal from the east-wing door, Manu’s rough blocking of her movement, and Tristan’s cold distance “to protect her” all share the same structure: power presses down, information is withheld, and Amara is expected to comply.

The theme is not that protection is evil, but that protection without consent becomes another form of control.

Tristan’s secrecy is especially complicated.

He genuinely wants to keep her safe from Shadow, yet by refusing to tell her the truth, he positions her as a childlike figure who cannot handle reality. This strips her of the ability to make informed choices about her own risk.

Her anger when he finally confesses is therefore less about the danger itself and more about the insult of being managed.

She says she is not “something to be taken,” which is the emotional core of this theme: autonomy is not just freedom of movement, it is the right to be treated as a full person whose consent matters.

The plot keeps proving her correct.

Because she does not know the real stakes, she unintentionally steals the letter, wanders into the east wing, and becomes a target for Cordelia.

In other words, secrecy meant to guard her actually increases danger.

Even the staged garden violence is a kind of manipulation carried out “for the greater good,” and it makes Amara question her own reality.

Dr. Shadow’s gaslighting through Tristan — denying he exists and calling her perceptions dreams — is another brutal example of autonomy being undermined via control of narrative.

The book uses these dynamics to show that truth is not a luxury; it is a safety tool. When Amara is finally given honesty, she can consent to intimacy with Tristan on her own terms and can understand the cost of staying.

The theme closes without a neat victory: Shadow returns, meaning risk remains. But Amara is no longer in the dark.

The novel suggests that autonomy does not always remove danger, yet it changes the moral shape of living with danger.

Choosing with open eyes is very different from being trapped by other people’s silence.