Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life Summary and Analysis

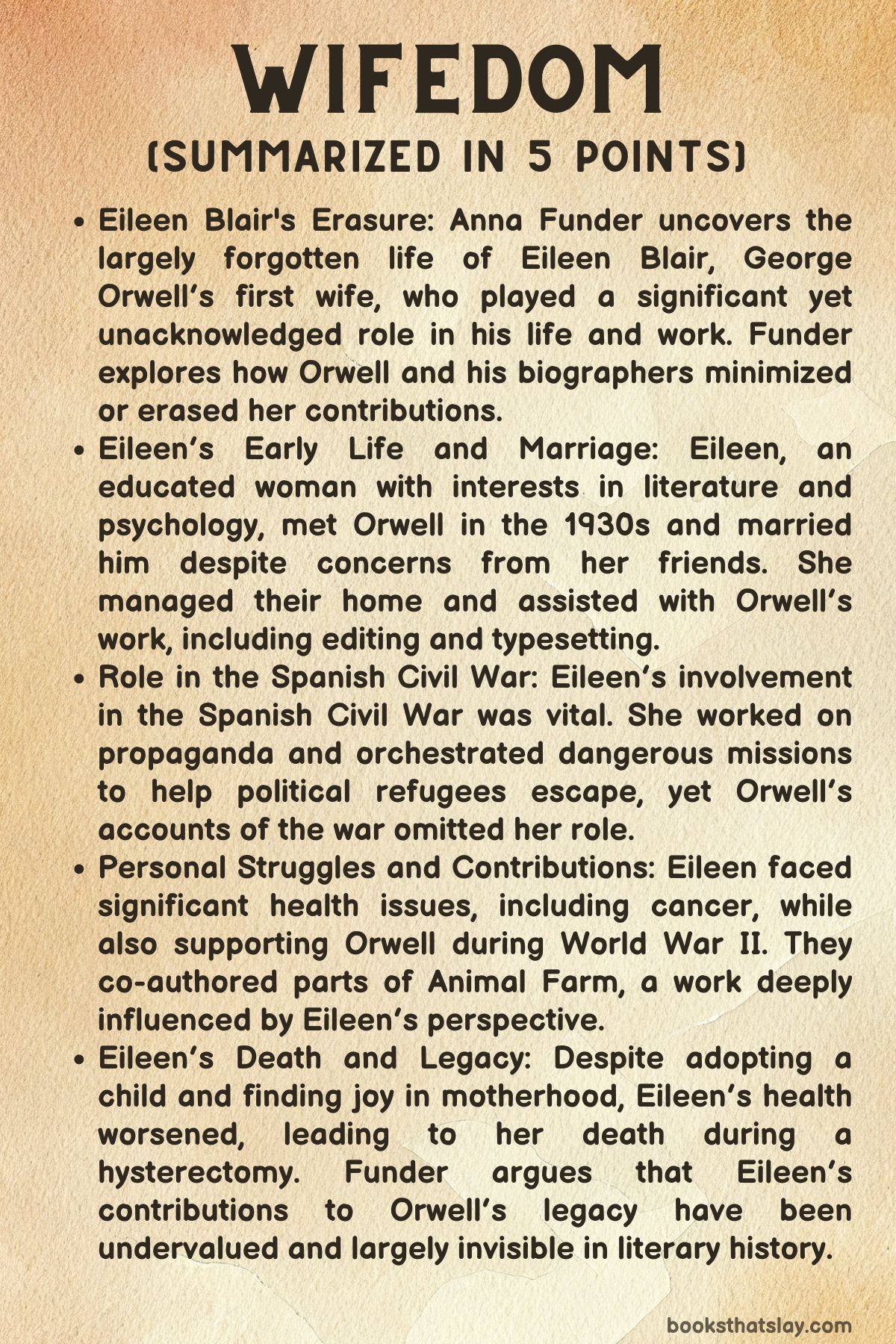

Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life, published in 2023 by Anna Funder, is a compelling exploration of Eileen Blair, the largely forgotten first wife of George Orwell. Blending biography, fiction, and literary analysis, Funder sheds light on the life of a woman whose contributions and sacrifices have often been overshadowed by her famous husband.

The book not only unearths Eileen’s vital role in Orwell’s personal and professional life but also delves into the broader issue of how women’s domestic labor has historically been rendered invisible. Funder skillfully combines historical research with imaginative reconstructions, offering a rich portrait of Eileen’s inner world.

Summary

Anna Funder’s Wifedom opens with Eileen Blair composing a letter to her friend Norah, an act that frames much of the narrative.

As Funder juxtaposes Eileen’s life with her own motivations for writing the book, we learn that Funder’s curiosity about Eileen’s erasure from Orwell’s biographies was sparked by a brief and insufficiently explained passage in Orwell’s works.

This leads her to investigate Eileen’s life, uncovering how her contributions and the unpaid domestic labor she performed—reflective of many women’s experiences—have been largely disregarded by history.

Eileen, born to a middle-class Anglo-Irish family, had a passion for literature and psychology during her college years. Meanwhile, George Orwell (born Eric Blair) grew up in England but spent time in Burma, where his disillusionment with imperialism and power structures began.

Eileen and Orwell’s paths crossed at a dinner party, where Orwell declared his intent to marry her.

Despite her friends’ concerns, Eileen wed Orwell in 1936, and they moved into a small cottage in Wallington.

Here, Eileen took on the bulk of household duties, all while editing and typesetting Orwell’s works, a laborious task that was never acknowledged in Orwell’s writings or by his biographers.

The story shifts to the Spanish Civil War, a period of high political tension. Orwell’s well-known Homage to Catalonia largely ignores Eileen’s pivotal role in these events. Contrary to typical portrayals of her as merely supportive, Eileen was deeply involved in the propaganda efforts for the Republican side and played a critical role in facilitating the escape of high-profile members of the Independent Labour Party.

Her actions put her under constant surveillance from Stalinist spies, but her quick thinking and resourcefulness ensured her and Orwell’s safe departure from Spain.

Back in England, Eileen and Orwell’s health deteriorated—Eileen from recurring, painful cysts, and Orwell from the tuberculosis that would eventually claim his life.

The onset of World War II compounded their struggles. Eileen’s brother’s death in combat plunged her into depression, but she continued to work, supporting both herself and Orwell.

Despite his increasing dependence on Eileen, Orwell had multiple affairs. Still, the two collaborated on Animal Farm, a work marked by Eileen’s influence.

After Animal Farm was completed, Eileen’s condition worsened, but her spirits were briefly lifted by the adoption of a son, Richard. Motherhood brought her great joy, though her health was rapidly declining.

She scheduled a hysterectomy, opting for a cheaper procedure, likely to avoid burdening Orwell financially. Tragically, she died during the operation.

Devastated, Orwell returned from his travels to care for their son with the help of a nurse. As he struggled to finish 1984, Orwell’s health worsened, leading to his eventual death in 1950.

The book closes with a poignant reflection from Eileen’s friend Norah, drawing a bittersweet conclusion to Eileen’s story and the legacy of her unrecognized contributions.

Characters

Eileen Blair (née O’Shaughnessy)

Eileen Blair is the central figure of Wifedom, and Anna Funder uses her life as a lens through which to examine the often invisible labor of women. Eileen was born into a middle-class Anglo-Irish family and was highly educated, having pursued literature and psychology in college. These interests suggest that she was intellectually vibrant and independent, traits that drew Orwell to her.

Despite her accomplishments, Eileen’s life was largely defined by her role as the supportive wife of George Orwell. Once married, she took on the role of a domestic caretaker, handling most of the household tasks and working as an unacknowledged contributor to Orwell’s literary career. Eileen’s personal ambitions and needs were often subordinated to Orwell’s, a dynamic that highlights Funder’s exploration of the erasure of women’s contributions in historical narratives.

Eileen’s strength and complexity emerge further in the Spanish Civil War, where she worked not just as a supportive wife but as an active participant. Her intelligence and bravery were critical in helping Orwell and others escape from danger, a role that has been systematically downplayed or omitted by Orwell’s biographers.

Eileen’s suffering, both physical and emotional, is a major part of the story. She endured painful cysts, struggled with the grief of losing her brother in World War II, and had to contend with Orwell’s infidelities. Despite these hardships, she continued to work, support Orwell, and contribute to his writings, notably Animal Farm.

Her death during surgery, weakened by years of anemia and emotional strain, encapsulates the tragic cost of her invisible labor and personal sacrifices.

George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair)

Orwell is both a towering literary figure and a deeply flawed man in Wifedom. The biography portrays him as a man who depended on Eileen’s labor—both emotional and physical—while consistently failing to acknowledge her contributions. Orwell is depicted as self-centered and obsessive about his writing, often at the expense of his personal relationships.

His early life in Burma, where he experienced and became disillusioned with colonialism, set the stage for his later literary and political concerns. These experiences formed the backdrop for his political writings, which Eileen supported, edited, and, in some ways, co-authored through her intellectual partnership with him.

Although Orwell is often portrayed as a champion of social justice in his works, Funder’s portrayal shows him as hypocritical in his personal life. He is often unfaithful to Eileen, having affairs with multiple women, including some of her close friends. Even as Eileen faces significant health problems, Orwell remains focused on his career.

His behavior during her illness, including leaving her during her final surgery, underscores his emotional detachment and selfishness. Orwell does suffer from his own health issues, particularly tuberculosis, and his later years are marked by a kind of internal struggle, as he raises his adopted son Richard and finishes 1984 under increasingly dire circumstances.

Nonetheless, the overwhelming impression left by the narrative is one of Orwell as a man who took more than he gave, particularly from Eileen.

Funder (Narrator/Author)

Anna Funder plays an essential role in the narrative, blending her voice with the biographical and fictionalized account of Eileen’s life. As the author and a central character, Funder provides critical commentary on the erasure of women’s contributions, both historically and in the present day. Her decision to explore Eileen’s life stems from her dissatisfaction with Orwell’s biographies, which gloss over Eileen’s role in his success.

Funder acts as both investigator and storyteller, inserting herself into the narrative by drawing parallels between Eileen’s domestic struggles and the broader feminist concern about the invisibility of women’s labor.

Funder is deeply concerned with the politics of memory and historiography, using Eileen’s life to explore how history is written and who is remembered. Her presence in the book also serves to emphasize the personal stakes of this historical recovery. By including scenes from her own life and reflections, Funder underscores the continued relevance of Eileen’s story and the erasure of domestic labor in contemporary society.

Through this interweaving of past and present, Funder challenges the reader to reflect on the broader issue of women’s roles, both visible and invisible, in shaping history.

Norah (Eileen’s Friend)

Norah serves as an important emotional touchstone in the book, representing a connection to Eileen’s earlier, more carefree life before she became enmeshed in Orwell’s world. The book both begins and ends with a letter Eileen writes to Norah, framing the narrative with Eileen’s perspective and voice.

Norah’s role in the story is as a witness to Eileen’s transformation and eventual tragedy. She is one of the few people who seems to fully grasp the extent of Eileen’s sacrifices and the toll her marriage to Orwell took on her.

Norah’s inclusion in the narrative, particularly in the final sections where the book returns to the letter from Eileen, offers a poignant counterbalance to Orwell’s dominating presence. It provides a more intimate, personal perspective on Eileen’s life.

Sonia Brownell (Orwell’s Second Wife)

Sonia Brownell appears towards the end of the book, entering Orwell’s life after Eileen’s death. Her presence serves as a kind of replacement for Eileen, though she is not depicted as having the same level of involvement in Orwell’s work.

Orwell’s marriage to Sonia is portrayed as more practical than passionate, especially given Orwell’s rapidly declining health. Sonia’s role in the narrative is relatively brief but significant, as she helps care for Orwell during his final days. However, unlike Eileen, Sonia’s contributions to Orwell’s life and work do not come at the same personal cost, since Orwell dies shortly after their marriage.

Her presence in the story highlights the idea of Eileen’s irreplaceability, despite Orwell’s attempt to move on with his life after her death.

Avril Blair (Orwell’s Sister)

Avril Blair, Orwell’s sister, plays a secondary role in the story but is nonetheless significant. She helps Orwell care for his son Richard after Eileen’s death, particularly when Orwell’s health begins to decline.

Avril’s presence in Orwell’s life is pragmatic—she assists with household management and child-rearing, but her relationship with Eileen seems distant. The friction between Avril and some of the hired help, particularly the nurse Susan, suggests a sharp and domineering personality.

While Avril’s loyalty to her brother is clear, her involvement in the domestic sphere after Eileen’s death highlights how different women in Orwell’s life were called upon to perform invisible labor, although none with the same depth of emotional investment as Eileen.

Richard Blair (Adopted Son)

Richard Blair, the son Eileen and Orwell adopt towards the end of Eileen’s life, represents a brief moment of happiness for Eileen. After years of emotional and physical hardship, Eileen finds joy in being Richard’s mother, and those close to her notice a revival in her spirit.

However, Eileen’s declining health and her death shortly after Richard’s adoption suggest that this newfound happiness was tragically short-lived. After Eileen’s death, Richard becomes Orwell’s responsibility, though much of the caregiving is done by hired help and Orwell’s sister Avril.

Richard’s presence in the narrative serves as a final testament to Eileen’s desire for a family, but also to the impermanence of her joy.

Analysis and Themes

The Erasure of Women’s Domestic Labor in Historical Narratives

One of the most intricate themes in Wifedom: Mrs. Orwell’s Invisible Life is the erasure of women’s domestic labor from historical and literary narratives. Anna Funder crafts a compelling argument around how Eileen Blair’s life, particularly her intellectual contributions and domestic labor, has been systematically erased not only by Orwell himself but by the biographers who followed.

Funder uses this erasure to critique a broader historical trend in which women’s domestic roles are not merely overlooked but actively diminished in accounts of historical figures and events.

Eileen’s contributions, whether in editing Orwell’s work or running their household, are devalued, reflecting a historical bias that prioritizes male achievements while marginalizing the labor that underpins them.

Funder expands this critique beyond the historical moment of Orwell’s life to explore how the invisible labor of women continues to shape literary and historical narratives. She demonstrates the persistence of these gendered silences.

The Intersection of Public and Private in Political Activism

Another nuanced theme in the book is the intersection between public and private life in the realm of political activism, as seen in Eileen’s role during the Spanish Civil War. While Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia frames his involvement in the war as primarily ideological, Funder illuminates how Eileen’s actions straddle the personal and political in more complex ways.

Eileen’s work, organizing escape routes for Independent Labor Party members and producing propaganda, is deeply tied to her domestic role and her personal relationships.

The tension between her domestic obligations and her political engagement reflects a broader question about how women’s activism is often relegated to the background, despite its significant impact on public events.

Funder suggests that the invisibility of women like Eileen within historical narratives of political activism reinforces the idea that public achievements—especially those dominated by men—are what truly matter. Women’s contributions remain peripheral, even when they are critical to the outcomes of these movements.

The Psychological Toll of Subjugation in Marriage

A key theme that Funder explores in detail is the psychological toll of subjugation within marriage, especially when one partner is a prominent public figure. Eileen’s marriage to Orwell, which is marked by a deep imbalance of power, not only professionally but also emotionally, serves as a lens through which Funder critiques the psychological impact of being married to a celebrated figure.

The strain of performing domestic labor while being overshadowed by Orwell’s literary fame leads to an emotional and intellectual erasure that compounds over time. Funder captures the dissonance Eileen faces: she is intellectually capable, yet her contributions to Orwell’s work are undervalued, and she is relegated to the role of caretaker.

The weight of Orwell’s affairs, coupled with Eileen’s deteriorating health and her inability to pursue her intellectual ambitions, underscores the emotional cost of living in a marriage where one’s existence is defined primarily by one’s husband’s needs and achievements.

This dynamic leads to a profound internal conflict for Eileen, whose sense of self is constantly undermined by the subjugating expectations of her marriage.

The Paradox of Female Empowerment through Maternal Roles

Funder presents a complex meditation on the paradox of female empowerment through maternal roles, particularly in the final stages of Eileen’s life. Eileen’s adoption of Richard brings her a new sense of purpose and fulfillment, and Funder highlights how motherhood revives her emotional and physical energy, even as her illness worsens.

Yet, this empowerment is fraught with contradictions. While motherhood gives Eileen a source of joy and meaning, it also reinforces societal expectations of women as primarily nurturers and caretakers.

Funder’s exploration of this paradox reflects a broader tension in feminist thought: the question of whether motherhood can be both a liberating experience and a vehicle for further entrenchment in traditional gender roles.

Eileen’s renewed vitality in motherhood suggests that, for some women, maternal roles provide a profound sense of identity, but this is counterbalanced by the reality that such roles often limit women’s opportunities for intellectual or professional fulfillment.

The Gendered Dynamics of Grief and Legacy

In the final sections of Wifedom, Funder turns her attention to the gendered dynamics of grief and legacy, particularly in the wake of Eileen’s death and Orwell’s subsequent life and literary career. Orwell’s grief, though palpable, is portrayed as distant and more focused on his own suffering than on the loss of Eileen as an individual.

Funder critiques Orwell’s posthumous legacy-building efforts, which include his attempts to raise Richard and finish 1984, as being largely self-serving. His emotional detachment from Eileen’s death mirrors the erasure of her identity in his writing.

The way Orwell moves on, remarrying Sonia Brownwell and seeking companionship to continue his own life’s work, emphasizes a masculine mode of grief that prioritizes personal legacy over emotional depth. In contrast, the narrative closes with Norah, Eileen’s friend, offering a feminine counterpoint to Orwell’s detached grief.

Norah’s reflections bring a different perspective on loss—one that centers Eileen’s life, experiences, and unacknowledged contributions to Orwell’s success. This contrast highlights the divergent ways men and women are often remembered or forgotten in the wake of death, with male figures like Orwell achieving lasting fame, while women like Eileen remain relegated to the margins of memory.

The Fictionalization of Historical Gaps as a Feminist Literary Strategy

Finally, Wifedom engages with the theme of fictionalization as a feminist literary strategy to recover lost or erased histories. Funder’s decision to blend historical fact with imagined scenes and her own personal narrative speaks to the limitations of historical records, particularly when it comes to marginalized figures like Eileen.

By filling in the gaps with fiction, Funder challenges the traditional boundaries of biography and scholarship. She suggests that the erasure of women’s lives from history necessitates imaginative reconstruction.

This method allows Funder to not only tell Eileen’s story but also to critique the process by which some lives are deemed worth recording, while others are dismissed. The blending of fact and fiction becomes an act of defiance, reclaiming the agency of women who have been rendered invisible by patriarchal historical practices.

This thematic approach offers a powerful reflection on the nature of history itself—how it is constructed, who it serves, and who it excludes. Funder’s experimental narrative form thus serves as a feminist intervention into the literary and historical canon.