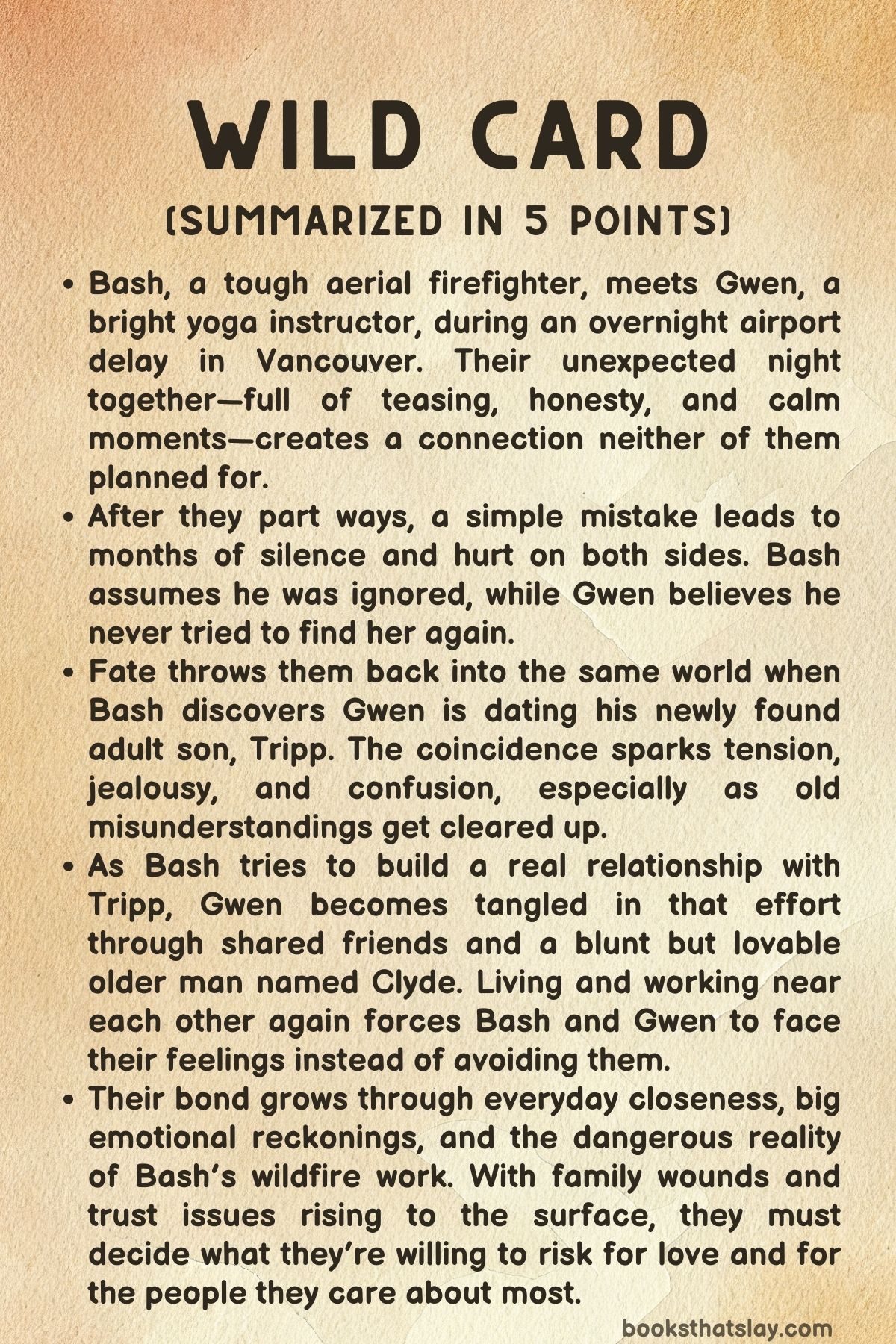

Wild Card by Elsie Silver Summary, Characters and Themes

Wild Card by Elsie Silver is a contemporary romance set against the rugged backdrop of aerial firefighting and small-town life. The story follows Sebastian “Bash” Eaton, a hard-edged, duty-driven pilot who discovers he has an adult son and is still reeling from the shock.

On a stormy night in an airport, he meets Gwen Dawson, a bright, independent yoga instructor whose calm strength cuts through his defenses. Months later, a wild coincidence throws them back together under messy circumstances. What starts as a one-night connection becomes a slow, complicated chance at love, family, and choosing a future that finally fits. It’s the 4th book in the Rose Hill series by Silver.

Summary

Bash Eaton, a thirty-nine-year-old aerial firefighter from Calgary, is stuck overnight in the Vancouver airport when a snowstorm cancels flights. He’s exhausted, angry, and fed up with the chaos.

At the rebooking desk he intervenes when a rude passenger berates a young agent, then accepts there’s nowhere to sleep except the terminal. Looking for a quiet spot, he ends up at a crowded airport bar and takes the last small table.

Gwen Dawson, a twenty-seven-year-old yoga instructor returning to Toronto after a retreat in Mexico, spots the empty chair at his table and sits without asking. Bash bristles at her easy cheer, but Gwen’s playful confidence disarms him.

She teases his sour mood, orders him an overly sweet lime margarita, and pulls him into conversation.

Over drinks, they trade stories and sarcasm. Gwen admires his work flying planes into wildfires to drop water and retardant, while Bash learns that Gwen faces constant condescension in her own career because she doesn’t match people’s shallow expectations of a “typical” yoga teacher.

Their banter turns warm. Gwen refuses to spend the night miserable in one place, so she drags him around the quiet airport.

They race on a moving walkway, laugh breathlessly, and sit by the windows watching the snow fall. In the calm, Bash admits what has been eating at him: he has just met his twenty-four-year-old son, Tripp Coleman, for the first time.

Tripp’s mother left town years ago without telling Bash she was pregnant. Bash is stunned, grieving lost time, and unsure how to be a father to a grown man.

As dawn approaches, Bash asks for Gwen’s number. She gives it, hesitant and vague about her last name because she moves often, but Bash insists he wants to see her again.

They share coffee, talk about her dream of opening her own studio, and part for separate flights with the sense that the night mattered more than either expected. After landing, Bash texts her immediately and again two weeks later.

Gwen never replies. Bash assumes he’s been ghosted and spends the next eight months trying to accept it.

Eight months later, Bash travels to West Vancouver for Tripp’s twenty-fifth birthday party at the lavish home of Tripp’s mother, Cecilia, and her husband Eddie. Bash feels awkward among the wealthy guests, but Tripp greets him warmly and their fragile new bond seems to be growing.

Then Bash sees Gwen at the party. Tripp introduces her as his girlfriend.

Bash and Gwen are both stunned; neither knew the other was connected to Tripp.

Tension spikes when Tripp makes a careless, controlling remark about Gwen’s snacking. Bash snaps at him for the disrespect, and Gwen backs Bash up with sharp humor before retreating to the house.

Bash follows her into a powder room. He accuses her of ignoring his messages and dating his son anyway.

Gwen fires back that Bash never contacted her. When he shows his phone with two messages marked delivered, Gwen grabs it and notices the contact: “Gwen Margaritas,” with a number one digit off from hers.

She realizes Bash has been texting the wrong number the entire time. Gwen explains she waited months for him to reach out and would have answered if she had known.

Bash is crushed by how a single mistake erased their chance, and he storms out before they can sort through the mess.

Months pass. Bash continues rebuilding a relationship with Tripp while carrying the ache of Gwen.

After a hockey injury sidelines Tripp, Bash checks on him, then drives his elderly friend Clyde to dialysis. Clyde, blunt and sly, notices Bash’s misery and pushes him to call Gwen, but Bash refuses.

He believes pursuing Gwen while Tripp is attached would destroy the father-son bond he’s trying to build.

A turning point comes at a trivia night in Rose Hill Reach. Bash walks in with friends and discovers Gwen is there too—now teaching at Bliss Yoga in Rose Hill on a one-year contract.

The surprise rattles him, and he flees before anyone can ask questions. Gwen, meanwhile, is trying to focus on her new life.

Clyde shows up for private yoga lessons, grumpy and suspicious, yet strangely endearing. Bash begins dropping Clyde off for class, creating a steady, uncomfortable orbit between Bash and Gwen.

Their attraction sparks every time they cross paths, but Bash keeps his distance, still unsure whether Gwen and Tripp are truly done.

On St. Patrick’s Day, Bash—worried about Clyde’s failing kidneys—offers to be tested as a donor.

He matches. Gwen finds out on the eve of the procedure, overwhelmed with gratitude.

When Bash waits early in the lobby because Clyde looks weak, Gwen breaks down in relief and throws her arms around him. Bash holds her, and their restraint cracks.

Clyde, delighted, announces Bash has invited Gwen to a pre-surgery party. She accepts.

After the successful surgery, Clyde asks Gwen to move in as a paid helper, since she’s about to lose her apartment above the studio. Bash, startled and prickly, insists Clyde will recover at Bash’s home and declares Gwen will stay there too.

Clyde’s goal is obvious: he wants the two of them under one roof.

The arrangement becomes even messier when Tripp shows up at Bash’s house and flirts with Gwen, asking her out again. Gwen refuses firmly, but Bash walks out in jealousy before hearing her answer.

While Bash is away fighting fires, Gwen worries nonstop. They begin texting again, slowly easing back into trust and desire.

When Bash returns drained and near burnout, Gwen takes care of him with grounding exercises, oils, and quiet support. In the safety of her presence, Bash opens up about the stress of his job and the fear of being left.

Gwen shares her own history: an estranged, controlling father who threw her out at eighteen. Their bond deepens into something neither wants to name yet.

Bash throws Gwen a thoughtful, joyful birthday filled with small-town warmth. The day is interrupted when Tripp arrives with expensive gifts and a pushy apology.

Gwen rejects him, and Bash orders him out. Soon after, Bash surprises Gwen with a flight in his small plane, a gift that feels like a promise.

Still, the unresolved knot around Tripp tightens. Tripp confronts them at the yoga studio after learning they disappeared together at his birthday party.

Bash admits he met Gwen first, months before Tripp did. Tripp erupts, accusing both of betrayal and revealing the pain of believing his whole life that Bash didn’t want him—an old lie Cecilia fed him.

Bash apologizes for the lost years but refuses to give Gwen up. Tripp storms off, devastated.

Bash later spots Gwen hugging Tripp in town and assumes she’s choosing his son. Gwen tells Bash he has to face his guilt and repair things with Tripp or their future will stay poisoned.

They separate angrily for the night. A wildfire flares near town, forcing evacuations.

Gwen, haunted by Clyde’s grief over possessions left in his remote cabin, drives there before blockades close. She loads Clyde’s treasured belongings into her truck and tries to protect the property through the night.

With no cell service, she becomes trapped as flames advance.

Bash learns she’s missing and, while flying fire suppression, breaks protocol to search for her. He spots Gwen and her truck from the air, calls in rescue, and clears a safe path with water drops.

A ground crew escorts Gwen out. At the blockade, Bash runs to her, shaken with relief.

They apologize, confess their love, and admit they want the same future. Tripp witnesses Bash’s frantic devotion and finally understands the depth of what they share.

He gives them his blessing, even if he needs time to adjust.

Months later, Bash and Gwen live together, steady and happy. Bash builds Gwen a lavender-lined lakeside studio, and she considers buying the town yoga space.

Their circle of friends and family expands, including a warmer, growing bond between Bash and Tripp. In the epilogue, their life continues to solidify—marriage, a child on the way, and a private symbol of their story when Bash names his repainted plane “Wild Card” after Gwen.

Characters

Bash

Bash is a thirty-nine-year-old aerial firefighter whose rugged exterior is both a professional necessity and a personal shield. In Wild Card, his gruffness reads at first like simple irritability, but it quickly reveals itself as the residue of exhaustion, a life built on high-stakes responsibility, and a deep fear of being left behind.

His job—flying into wildfires—mirrors his inner world: he is drawn to danger because he knows how to function inside it, while ordinary emotional risk leaves him clumsy and volatile. The late discovery that he has an adult son detonates his sense of identity, forcing him to confront grief for lost years and anger at being denied the choice to be a father.

Bash’s arc is about learning that strength is not the absence of need; it is the willingness to admit it. His decision to donate a kidney to Clyde, his eventual openness about burnout, and his refusal to surrender Gwen even when the situation is messy all show a man learning to stay present instead of retreating into silence or fury.

By the end, his love becomes less possessive and more grounded, shaped by humility, repaired family ties, and a new understanding of home.

Gwen

Gwen, a twenty-seven-year-old yoga instructor, enters the story as a bright, quick-witted counterweight to Bash’s stormy temperament, but her optimism is not naïveté—it is a practiced form of survival. She has spent years rebuilding herself after being rejected and controlled by her father, and that history gives her a sharp radar for disrespect, whether it comes from strangers stereotyping her career or from Tripp’s careless comments about her body and food.

In Wild Card, Gwen’s emotional power lies in her steadiness: she knows how to hold space for others while still refusing to shrink herself. Her mobility and reluctance to share a last name early on hint at a life lived in self-protection, yet her bond with Bash slowly draws out her desire for roots.

She is both nurturing and challenging, soothing Bash’s burnout with oils, music, and grounding rituals, but also insisting he face the damage with Tripp rather than hiding in guilt. Gwen’s love is active, not passive; she risks herself to save Clyde’s cabin, chooses to stay instead of running to Costa Rica, and demands honesty in the relationship.

She is ultimately a figure of chosen belonging—someone who builds safety not through avoidance, but through courageous commitment.

Tripp Coleman

Tripp is Bash’s twenty-four-year-old son, shaped by absence and the story he was told about that absence. He begins as charming but immature, used to privilege and thoughtless entitlement, which comes out in casual sexism toward Gwen and in his dramatic attempts to win her back with expensive gifts.

Yet in Wild Card, Tripp is also a study in emotional whiplash: he has to absorb that his mother lied about his father, that Bash is not the villain he imagined, and that the woman he dated is in love with that father. His anger is less about Gwen “betraying” him and more about the collapse of the narrative that organized his life.

When he lashes out, it is the flailing of someone who feels replaced and humiliated, not just romantically but existentially. Over time, Tripp’s growth is visible in how he shifts from reactive to reflective: he apologizes, recognizes Bash’s devotion during the fire rescue, and accepts that rebuilding their father-son bond will take patience.

He ends the story still adjusting, but no longer trapped in resentment, making him a believable portrait of adulthood arriving late through crisis.

Clyde

Clyde is the abrasive, stubborn elderly man Bash helps to dialysis, and he becomes the sly emotional engine of the novel. At first he presents as cranky and paranoid, especially about medicine and surveillance, but his harshness is a mask for vulnerability that he refuses to sentimentalize.

In Wild Card, Clyde functions as both comic relief and quiet moral compass. His love for his late wife Maya, and the trauma of losing her to medical misjudgment, explain his mistrust and his fierce attachment to what remains of her life.

He is not soft-spoken wisdom; he is blunt, meddling, and sometimes infuriating, which makes his care feel earned rather than performative. Clyde orchestrates proximity between Bash and Gwen because he sees what they cannot admit, and he pushes Bash toward emotional honesty the way a coach pushes an athlete past fear.

His illness gives urgency to the plot, but his real gift is relational: he forces characters into truth by refusing to tiptoe around them. Even when he jokes or needles, he is building a family around himself, making his recovery feel like a shared victory rather than a private medical event.

Cecilia

Cecilia is Tripp’s mother and Bash’s high-school relationship, and she remains a chilly, controlling presence. Her decision to leave without telling Bash she was pregnant is the foundational wound of the story, not only because it stole Bash’s chance at fatherhood, but because it burdened Tripp with a false story of abandonment.

In Wild Card, Cecilia embodies the kind of power that operates through withholding: she maintains distance at the birthday party, avoids accountability, and allows a narrative of Bash as a deadbeat to calcify. Yet she is not written as a cartoon villain; her iciness hints at fear, pride, and perhaps a need to justify a life she built without Bash.

Her role is less about active cruelty in the present and more about the long shadow of a past choice, showing how silence can be as damaging as aggression.

Eddie

Eddie, Cecilia’s husband, plays a small but meaningful part as a contrast to Cecilia’s coldness. In Wild Card, he welcomes Bash warmly into a world of wealth Bash feels alien to, signaling a decency that doesn’t depend on biology or status.

Eddie’s kindness subtly reframes Tripp’s upbringing: even with Cecilia’s deception, Tripp did not grow up without male care; he grew up with a stepfather who treated him (and eventually Bash) with basic dignity. Eddie represents quiet stability, someone who doesn’t need to dominate the narrative to improve it.

West

West is one of Bash’s close friends and part of the bowling-and-bar-night circle that grounds Bash socially. In Wild Card, West represents community and the softer domestic responsibilities Bash is learning to value; his panic over saving thirty horses during the wildfire shows how much life in Rose Hill depends on mutual backup.

West’s presence emphasizes Bash’s capacity for loyalty and camaraderie outside romance, reinforcing that Bash’s healing isn’t just about Gwen, but about letting himself be held by a broader network.

Ford

Ford joins the friend group and later becomes a focal point at his wedding to Rosie. In Wild Card, Ford’s role is to expand the social world around Bash and Gwen, offering a model of committed partnership that Bash begins to imagine for himself.

The wedding scene, where Bash is a groomsman and finds himself thinking about marriage, uses Ford as a mirror—showing Bash what a future could look like when love is chosen openly and celebrated.

Rhys

Rhys is another member of Bash’s circle and provides the accidental spark that reintroduces Gwen into Bash’s daily life. In Wild Card, his casual mention of his yoga instructor makes him an unwitting pivot point, but he also serves as a confidant space where Bash can admit how tangled everything feels.

Rhys’s easy social presence reinforces the theme that relationships don’t heal in isolation; people need ordinary friends around the extraordinary mess.

Tabitha (Tabby)

Tabby appears within Gwen’s female friend group, helping anchor Gwen in Rose Hill. In Wild Card, Tabby’s role is less plot-driving and more atmosphere-setting: she helps normalize Gwen’s life beyond Bash, giving Gwen a support system that isn’t romantic.

That matters because Gwen’s eventual choice to stay is not framed as dependency; she stays while still being held by friends and a career of her own.

Rosie

Rosie is part of Gwen’s circle and later Ford’s bride, and she helps translate Gwen into the town’s social fabric. In Wild Card, Rosie’s friendship offers Gwen a sense of belonging that doesn’t require proving herself, and her wedding functions as a narrative milestone: a communal celebration that parallels Bash and Gwen’s stabilized love.

Rosie’s steadiness reinforces the romance’s landing point—this is a town where chosen family can stick.

Skylar

Skylar, another of Gwen’s friends, mainly appears during trivia nights and wildfire news moments. In Wild Card, Skylar contributes to the texture of Gwen’s life as an independent person with routines, friendships, and reactions separate from Bash.

Her presence supports the theme that love should add to a life, not replace it.

Emmett

Emmett shows up during the wildfire evacuation as the friend Bash calls for help with a larger horse trailer. In Wild Card, Emmett is an example of immediate, practical solidarity—someone who responds to crisis without drama.

He reinforces Bash’s embeddedness in a community of capable people, which makes Bash’s eventual emotional openness feel safer and more plausible.

Greg

Greg appears briefly at the airstrip when Bash takes Gwen flying. In Wild Card, Greg’s function is to highlight Bash’s competence and comfort in his element.

By witnessing Bash in a workplace setting, Gwen—and the reader—sees him not as a closed-off man to fix, but as a skilled professional whose confidence reemerges when he shares his world with someone he trusts.

Beau

Beau is the rescue crew leader who escorts Gwen from Clyde’s cabin during the wildfire. In Wild Card, Beau represents the larger system of emergency response that Bash belongs to, and his professionalism underscores the stakes of Gwen’s risk.

He also acts as a boundary figure: he ensures Gwen’s safety so Bash can drop the role of savior long enough to be simply a terrified, relieved man in love.

Maya

Maya is Clyde’s late wife, present through memory and meaning rather than scenes. In Wild Card, she is the emotional key to Clyde’s mistrust of medicine and his fierce tenderness under the grumpiness.

The old marijuana strain she left behind becomes a symbolic bridge between grief and healing, allowing Clyde, Bash, and Gwen to share laughter without erasing loss. Maya’s presence reminds the story that love can survive as influence long after death.

Gwen’s Father

Though unnamed in the summary, Gwen’s father is a powerful offstage character because he shaped Gwen’s self-concept. In Wild Card, he embodies control disguised as tradition, kicking her out at eighteen for refusing to conform and leaving her to rebuild her worth from scratch.

His role is crucial in explaining why Gwen values autonomy so intensely, why she resists being boxed in—by stereotypes, boyfriends, or even the comfort of staying put—and why her eventual decision to commit to Bash is meaningful.

She is not repeating submission; she is choosing partnership on her own terms, in defiance of the man who tried to define her life for her.

Themes

Miscommunication and the Fragility of Second Chances

An overnight meet-cute at an airport becomes the emotional hinge of Wild Card because it is both intensely real and painfully fragile. Bash and Gwen connect in a way that feels rare to them: he’s a man who has learned to keep his world narrow and controlled, and she’s someone who survives by staying open, curious, and mobile.

Their night is a small pocket of honesty inside a chaotic terminal, and it sets up the idea that timing can be merciless even when two people are right for each other. The wrong digit in Gwen’s phone number is almost absurdly minor, yet the story treats it with the weight it deserves.

That single error creates eight months of silence, then a collision that reopens everything they thought they had lost. What matters is not just the mistake itself but what the mistake reveals about each character.

Bash interprets her silence as abandonment because he already expects to be left; Gwen interprets his silence as indifference because she has spent years being dismissed by people who thought they knew her place. Their assumptions aren’t random misunderstandings—they are emotional habits shaped by earlier wounds.

The book uses this thread to argue that second chances are not heroic moments arriving on cue. They are messy, uncomfortable, and often depend on whether people can challenge the stories they tell about each other.

When Bash learns Gwen never received his texts, his devastation isn’t only romantic. It’s existential: it confirms how easily life can slip past you while you think you’re being careful.

Yet the narrative doesn’t let him hide behind fate. He still must choose what to do next, especially once Gwen is tied to Tripp.

Their renewed proximity through Clyde and the town forces them to sit inside awkwardness instead of running from it. In that way, miscommunication becomes a test of character.

Do they retreat into pride and “appropriateness,” or do they risk honesty now that the cost is higher?

By the time they finally speak clearly—about desire, about guilt, about love—the story has already shown how silence can be as active and damaging as any cruel word. The resolution isn’t that conversations magically fix everything; it’s that communication is a deliberate practice, especially for people who’ve learned not to trust outcomes.

Wild Card treats clarity as an act of courage. It suggests that love doesn’t just arrive through chemistry or coincidence; it survives through refusing to let fear decide what another person meant.

Found Family, Care, and the Ways People Heal

The relationships around Bash and Gwen are not decoration; they are the mechanism through which both characters learn how to live differently. Clyde in particular becomes a catalyst for the kind of care that neither protagonist knows how to ask for.

Bash’s life as an aerial firefighter has trained him to be useful under pressure, to solve emergencies, and to measure worth through toughness. Gwen’s life as a yoga instructor has trained her to listen, soothe, and hold space, even when people underestimate her.

Clyde pulls them into a shared orbit where those strengths are needed in ordinary, daily ways. Caring for him after dialysis, teaching him yoga, cooking in kitchens, sitting on porches—these are intimate tasks that build trust without demanding that either person announce their feelings first.

What’s striking is how the book frames healing as communal instead of purely romantic. Bash’s burnout doesn’t resolve because Gwen loves him; it resolves because she models care without shaming him, and because his friends normalize vulnerability.

He talks to a mental health worker. He shows up to yoga.

He allows himself to be tired and comforted. That shift is mirrored in Gwen’s arc: her housing insecurity and her unease about belonging are eased not only by Bash’s eventual commitment, but by being welcomed into a circle that values her beyond her usefulness.

The bowling nights, trivia nights, and casual teasing are the texture of belonging she hasn’t had while drifting from contract to contract.

Clyde’s kidney storyline deepens this theme by tying love to risk and sacrifice in a grounded way. Bash’s decision to donate is not a grand performance; it’s a quiet acceptance that his body and life can serve warmth rather than danger.

Gwen’s gratitude after the surgery isn’t romanticized into debt; instead, it enlarges her sense that there are people worth staying for. Even Clyde’s crankiness and paranoia are treated with tenderness rather than mockery.

The book suggests that family is not only who shares blood, but who shares responsibility for each other’s continued existence.

In the end, the “family” Bash and Gwen build includes friends, mentors, and even the son who first made their love feel impossible. This matters because it reframes healing as a shared project.

Wild Card doesn’t pretend love erases old pain; it shows that pain becomes bearable when others help you carry it and when you let yourself be carried back.

Fatherhood, Accountability, and Redefining Masculinity

Bash discovering Tripp as an adult shatters his self-image, and the story uses that rupture to explore what accountability looks like when the past can’t be repaired in the usual ways. Bash didn’t abandon Tripp, but he must still face the consequences of absence.

The book refuses to make this easy for him. He can’t rewind time, and he can’t demand instant forgiveness just because he is biologically connected.

His instinct is to protect, to fix, to act—calling after Tripp’s injury, bristling at his disrespect toward Gwen, offering to donate a kidney to Clyde. These are expressions of care, but they are also the habits of a man who feels safest when he is needed.

Real fatherhood in Wild Card requires more than protective reflexes; it requires sustained emotional presence.

Tripp’s anger is written as legitimate grief. He has spent a lifetime believing a story about being unwanted, and even after the lie is exposed, the feeling doesn’t vanish.

When he confronts Bash and Gwen, his cruelty is a flare of confusion: he wants to know where he fits now that his father exists and now that his girlfriend’s affection has shifted. Bash’s temptation is to treat Tripp as a rival or a threat.

The story lets him feel that jealousy, then forces him to see why it’s destructive. Gwen’s insistence that Bash repair things with his son becomes a moral line in the book: love for her cannot be built on the ruins of his relationship with Tripp.

This dynamic also reframes masculinity. Bash is physically brave and socially blunt, but emotionally inexperienced.

He is used to environments where feelings are private and survival is the main value. Through Tripp, he confronts a different kind of risk: being seen as flawed, being told he isn’t enough, staying anyway.

The book maps that transition carefully. Bash apologizes without excuses.

He learns to listen even when he wants to argue. He allows his pride to be smaller than his desire for connection.

The final reconciliation is not a tidy bow; Tripp offers acceptance “with time,” and Bash respects that.

By showing Bash’s growth alongside his romance, Wild Card argues that love isn’t only about choosing a partner—it’s about choosing the kind of man you will be inside a larger web of obligations. Fatherhood becomes the arena where Bash learns tenderness without control, strength without domination, and accountability without self-hatred.

That lesson then makes his relationship with Gwen sturdier, because he is no longer trying to be invincible; he is trying to be present.

Autonomy, Belonging, and Choosing to Stay

Gwen’s life is defined by motion. She takes contracts, relocates easily, and keeps her future open because staying has historically meant being trapped inside someone else’s expectations.

Her estrangement from her father is the emotional root of this. Being thrown out at eighteen for refusing to accept his rules taught her that love can be conditional and that independence is survival.

So when she meets Bash, the intensity of their connection scares her not because it feels wrong, but because it feels like something that could cost her freedom. Over and over, Gwen measures whether love requires shrinking.

The story makes her answer clear: it doesn’t, not with the right person.

Her work as a yoga instructor reinforces this theme. People underestimate her professionalism, assume her body should match their idea of a “yoga type,” and treat her discipline as cute rather than skilled.

Gwen’s optimism is therefore not naïveté; it’s a chosen stance against a world that constantly tries to define her. When Bash respects her work, listens to her grounding practices, and takes her seriously as someone who can guide him, he becomes a partner who expands her sense of self rather than compressing it.

The lavender studio he builds later isn’t just a romantic gift. It is a physical acknowledgment that her dreams deserve roots.

Bash’s arc mirrors hers from the opposite direction. He has stayed in one town, one job identity, one emotional posture.

His fear is not containment but abandonment. The push and pull between them—her habit of leaving before she’s left, his habit of bracing for loss—creates a tension where belonging must be actively chosen.

Gwen’s decision to decline Costa Rica is the clearest example. She doesn’t give up travel because Bash asks; she chooses to stay because for the first time staying feels like her decision, not a compromise.

Her rescue mission to Clyde’s cabin during the wildfire is the same choice in action: she stays to protect what matters to her, even when no one told her to.

The theme reaches maturity when Gwen tells Bash she won’t run again and Bash believes her without trying to cage her. Belonging, in Wild Card, is not the opposite of autonomy.

It is what autonomy can produce when someone finally finds a place and people that make staying feel brave instead of dangerous. The ending—marriage, pregnancy, a shared home and community—lands not as a surrender of Gwen’s independence, but as proof that independence can include building a life with someone else.