Winesburg, Ohio by Sherwood Anderson Summary and Analysis

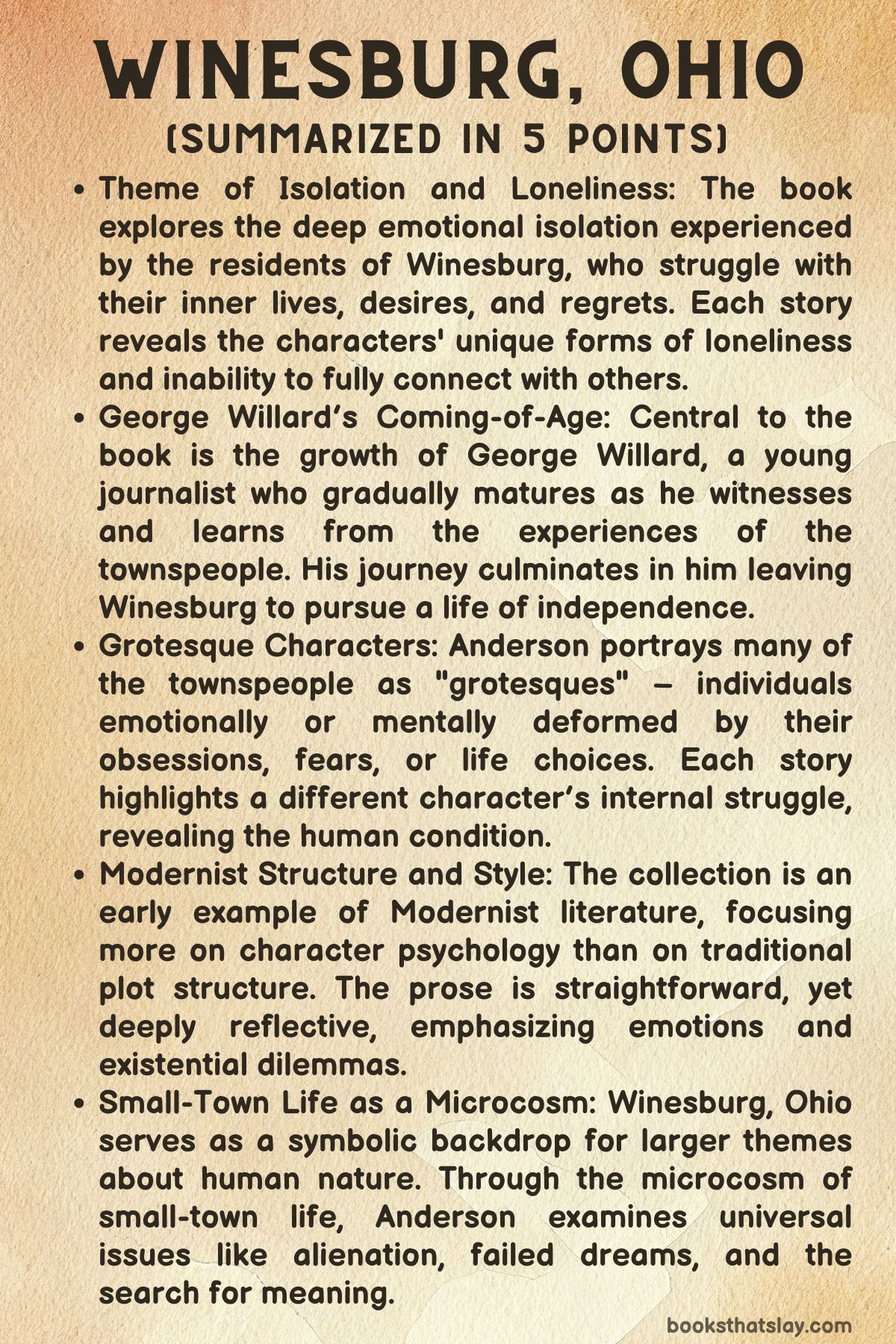

Winesburg, Ohio, published in 1919, written by Sherwood Anderson, is a classic collection of interconnected short stories that explore the complexities of small-town life in early 20th-century America. Set in the fictional town of Winesburg, Ohio, the stories revolve around the inner struggles of its characters, revealing their deep loneliness, frustrations, and desires.

The central figure, George Willard, a young journalist, gradually comes of age throughout the book, offering a sense of cohesion to the narrative. Anderson’s work is notable for its focus on character psychology over traditional plot, making it one of the pioneering texts of American modernism.

Summary

The first story in Winesburg, Ohio, titled “The Book of the Grotesque,” introduces an aging writer who, after a vivid, dreamlike experience, becomes convinced that those who fixate on a singular belief or truth ultimately deform themselves into “grotesques.”

This reflection leads the writer to collect various stories about such individuals, setting the tone for the tales that follow. Through this lens, the reader sees Winesburg as a town inhabited by people emotionally or mentally twisted by their obsessions, anxieties, and loneliness.

In “Hands,” we meet Wing Biddlebaum, a reclusive man who constantly fidgets with his hands, a habit that alienates him from the rest of the town. Years earlier, Wing had been a beloved schoolteacher in Pennsylvania, but after a false accusation of inappropriate behavior toward a student, his life unraveled.

Now, in Winesburg, his interaction with George Willard triggers a painful reminder of his past. His hands, once expressive tools for teaching, have become symbols of his disgrace and isolation.

“Paper Pills” focuses on Doctor Reefy, who spends his days jotting down philosophical musings on scraps of paper, only to crumple them and leave them scattered around his office.

He meets a young woman who comes to him for medical care after an unwanted pregnancy. They marry, but their brief happiness is cut short when she dies, leaving the doctor to mourn in solitude, clutching his discarded “paper pills.”

The third story, “Mother,” centers on George Willard’s relationship with his parents. His mother, Elizabeth Willard, is bedridden and suffers from illness, while his father, Tom, grows frustrated with their stagnant life.

Elizabeth is fiercely attached to George, believing he holds the key to the freedom she never had. At one point, she even contemplates killing Tom when he suggests that George should leave Winesburg to seek a better life.

Her desire for George’s future battles with her possessiveness, painting a tragic portrait of maternal love.

In “The Philosopher,” Doctor Parcival shares his nihilistic worldview with George. Having led a life filled with misfortune, Parcival is cynical and consumed by bitterness.

His teachings reflect a philosophy of universal suffering, and when he refuses to help after a child dies in an accident, he fears that the townspeople will turn against him.

Before George departs, Parcival urges him to remember that “everyone in the world is Christ and they are all crucified.”

In “Nobody Knows,” George engages in a brief and secretive sexual encounter with Louise Trunnion, a local girl. Afterward, George is overcome with shame and guilt, but he reassures himself that no one will ever find out.

This episode hints at George’s inner conflict as he transitions from adolescence to adulthood.

“Godliness,” a multi-part story, traces the life of Jesse Bentley, an ambitious farmer with grand visions of serving as an instrument of God. Obsessed with fulfilling a biblical destiny, Jesse becomes estranged from his daughter, Louise, who marries and has a son named David.

Jesse sees in David the heir he never had, hoping the boy will help him achieve his divine purpose.

However, Jesse’s intensity drives a wedge between them, and after a failed attempt to draw David into his prophetic mission, the boy runs away, leaving Jesse alone with his broken dreams.

In “A Man of Ideas,” Joe Welling is a man whose relentless spouting of philosophical ideas irritates the townspeople.

Despite his eccentricity, Joe wins respect when he forms a baseball team and strikes up a relationship with Sarah King.

Sarah’s family, known for being dangerous, is surprisingly charmed by Joe’s enthusiasm, and through this, he gains a measure of acceptance in the community.

“Adventure” follows Alice Hindman, who is consumed by the memory of her former lover, Ned Currie, who left her years ago. Unable to move on, Alice becomes increasingly isolated.

One rainy night, in an act of desperate rebellion, she strips off her clothes and runs outside, only to retreat back indoors, defeated. Alice resigns herself to a life of solitude, haunted by the idea that she will never escape her loneliness.

“Respectability” tells the story of Wash Williams, a man embittered by his wife’s infidelity. Filled with contempt for women, Wash tries to impart his hatred onto George Willard after witnessing him kiss Belle Carpenter.

However, George does not share Wash’s disillusionment and instead feels repelled by Wash’s toxic worldview.

In “The Thinker,” Seth Richmond, a brooding young man, feels out of place in Winesburg. He yearns for a life beyond the small town but is paralyzed by uncertainty.

When he learns that George is interested in Helen White, Seth grows jealous and seeks her out.

However, instead of the romantic encounter he anticipates, Helen encourages him to leave Winesburg, reinforcing his feelings of alienation.

“Tandy” tells the story of a young girl who is inspired by a drunken stranger’s prophecy. The man tells her that she has the potential to embody the qualities of strength, bravery, and love, qualities he collectively refers to as “Tandy.”

The girl adopts this name, finding a sense of identity and purpose in a town where people seem to struggle with meaning.

In “The Strength of God” and “The Teacher,” Reverend Curtis Hartman becomes obsessed with Kate Swift, a schoolteacher. His desire for her threatens his faith, leading him to spy on her from the church bell tower.

One day, he sees her praying and experiences a religious epiphany, believing that Kate is a divine messenger. However, Kate’s complex relationship with George adds further layers of confusion to the narrative, especially from George’s point of view.

In “Loneliness,” Enoch Robinson’s inability to form real relationships leads him to create imaginary companions. After his marriage fails, Enoch returns to Winesburg, where he remains isolated, his loneliness deepened by the loss of his fantasy world.

The final stories center on George Willard’s own awakening. In “Sophistication,” George, reeling from his mother’s death, spends an evening with Helen White, seeking solace in their shared sense of growing up.

The two reflect on their changing lives, their connection symbolizing a mutual understanding of their journey into adulthood. In “Departure,” George finally leaves Winesburg, boarding a train to start a new life.

Though nostalgic at first, he soon embraces the possibilities ahead, ready to move beyond the confines of his small-town upbringing.

Analysis and Themes

The Grotesque Nature of Human Experience and the Distortion of Truth

One of the most profound themes in Winesburg, Ohio is the idea that human beings, when consumed by a single obsession or principle, become grotesque. The concept of the “grotesque” is introduced in the opening story, “The Book of the Grotesque,” where the elderly writer observes that people warp and deform themselves by clinging too tightly to an idea or belief.

This grotesqueness isn’t physical but rather a distortion of the spirit and the mind. Anderson shows that when individuals attempt to live by an isolated truth—be it an obsession with faith, desire, or intellectual understanding—they become disconnected from the more comprehensive reality of life.

This alienation leads to their moral and emotional decay. Wing Biddlebaum’s compulsive behavior in “Hands” reflects his inability to escape a haunting accusation from his past, while Doctor Parcival’s embittered philosophy in “The Philosopher” underscores how a fixation on personal suffering distorts one’s understanding of human interconnectedness.

These characters, and many others in Winesburg, are examples of how Anderson weaves the theme of the grotesque into the fabric of everyday life. He suggests that to be human is to grapple with a constant tension between the search for meaning and the inherent fragmentation of experience.

Isolation, Loneliness, and the Failure of Communication

The theme of isolation is at the heart of Winesburg, Ohio, permeating the lives of nearly every character. Anderson portrays small-town life not as a communal paradise but as a breeding ground for profound loneliness.

The townspeople are trapped in their private struggles, and their inability to connect with others exacerbates their feelings of alienation. Communication, or rather the lack of it, is a recurring problem in the novel.

The characters are often portrayed as stifled, unable to express their deepest fears, desires, or griefs to those around them. For example, Elizabeth Willard in “Mother” is trapped in a failing marriage and plagued by regret over her wasted life, but her attempts to forge a deeper relationship with her son George are ultimately unsuccessful.

Similarly, in “Adventure,” Alice Hindman’s futile waiting for her lost lover symbolizes the emotional paralysis that grips many of the characters. Anderson’s portrayal of communication breakdowns highlights not only personal isolation but also a broader existential theme: the inherent difficulty of understanding and being understood.

This failure of communication leads to a sense of existential despair, as individuals struggle with the knowledge that they may never truly connect with another soul.

The Struggle Between Stagnation and Change in Small-Town Life

The tension between stagnation and the desire for change forms another major theme in Winesburg, Ohio. Many of Anderson’s characters are caught in a liminal space between yearning for escape and being tethered to the routines and expectations of small-town life.

Winesburg itself becomes a symbol of the limitations imposed by this environment—an insular, repressive space where ambitions and dreams often go unfulfilled. Yet, paradoxically, the familiarity and simplicity of small-town life also exert a powerful force, making it difficult for characters to break free.

George Willard’s coming-of-age arc represents the desire to move beyond the confines of Winesburg, culminating in his final departure in the story “Departure.” However, throughout the novel, other characters such as Seth Richmond in “The Thinker” and Enoch Robinson in “Loneliness” are examples of individuals who dream of escape but remain trapped by either circumstance or their own psychological limitations.

This theme reveals the ambivalence that Anderson feels towards rural life—it is simultaneously a space of comfort and suffocation, stagnation and potential transformation.

Sexual Repression, Guilt, and Despair

The characters in Winesburg, Ohio are often burdened by their unexpressed or repressed sexual desires. Anderson presents this as a source of both psychological torment and social alienation.

The small-town setting intensifies this, as the conservative moral fabric of Winesburg leaves little room for the open expression of desire, leading to guilt and repression. In “Hands,” Wing Biddlebaum’s past trauma, stemming from a false accusation of sexual misconduct, has rendered him fearful of any physical touch, resulting in his self-imposed exile.

His torment reflects not only the consequences of sexual repression but also the power of societal judgment in shaping personal identity. Similarly, George Willard’s sexual encounters, particularly in stories like “Nobody Knows,” highlight the confusion and shame associated with young sexuality in a repressive environment.

This struggle is echoed in Reverend Curtis Hartman’s crisis of faith in “The Strength of God,” where his voyeuristic obsession with Kate Swift leads him to believe that sin and spiritual epiphany are intertwined. Through these characters, Anderson explores how sexuality becomes a battlefield for control, guilt, and self-understanding.

He suggests that the repression of desire contributes to the deeper psychological isolation that pervades Winesburg.

The Inescapable Influence of the Past on Identity and Fate

Throughout Winesburg, Ohio, the characters are haunted by their pasts, which often dictate their current behaviors and attitudes. Anderson suggests that the past is inescapable, shaping the characters’ identities in profound and often tragic ways.

Doctor Reefy in “Paper Pills” and Elizabeth Willard in “Death” are both trapped in the emotional ruins of their youth, their present lives shaped by unfulfilled desires and unrealized potential. This sense of being unable to escape the past creates a fatalistic tone in many of the stories.

In “Godliness,” Jesse Bentley’s obsession with Old Testament imagery and his belief in his own prophetic destiny wreaks havoc on his family, particularly his grandson David. David is ultimately driven away by the weight of his grandfather’s expectations.

The past, in Anderson’s vision, not only informs who the characters have become but also acts as an almost oppressive force that shapes their futures. It prevents them from achieving true freedom or happiness.

Even George Willard, the novel’s protagonist, is not immune to this theme. His final departure from Winesburg is tinged with an understanding that, despite physically leaving, the emotional and psychological impact of his childhood will continue to influence his identity as he moves into adulthood.

The Fragility of Human Connections and the Search for Meaning

At its core, Winesburg, Ohio is a meditation on the fragile and fleeting nature of human connections. Anderson’s characters often seek meaning in their relationships with others, but these connections are frequently undermined by misunderstandings, miscommunications, or personal failings.

The search for meaning—whether through relationships, work, or personal philosophy—becomes a central struggle for many of the characters. In “Sophistication,” George Willard and Helen White share a brief moment of mutual understanding, but it is fleeting, underscoring the transient nature of such connections.

Likewise, Doctor Parcival’s plea to George in “The Philosopher” that “everyone in the world is Christ and they are all crucified” reflects the broader theme of human suffering and the difficulty of finding solace in a world that often feels indifferent to individual pain.

The novel suggests that while human beings crave connection and understanding, these desires are often thwarted by the very conditions of existence—loneliness, mortality, and the limitations of language.

Thus, Winesburg, Ohio becomes a profound exploration of the tension between the desire for meaning and the inevitable experience of isolation in the human condition.