Woman of Light Summary, Characters and Themes

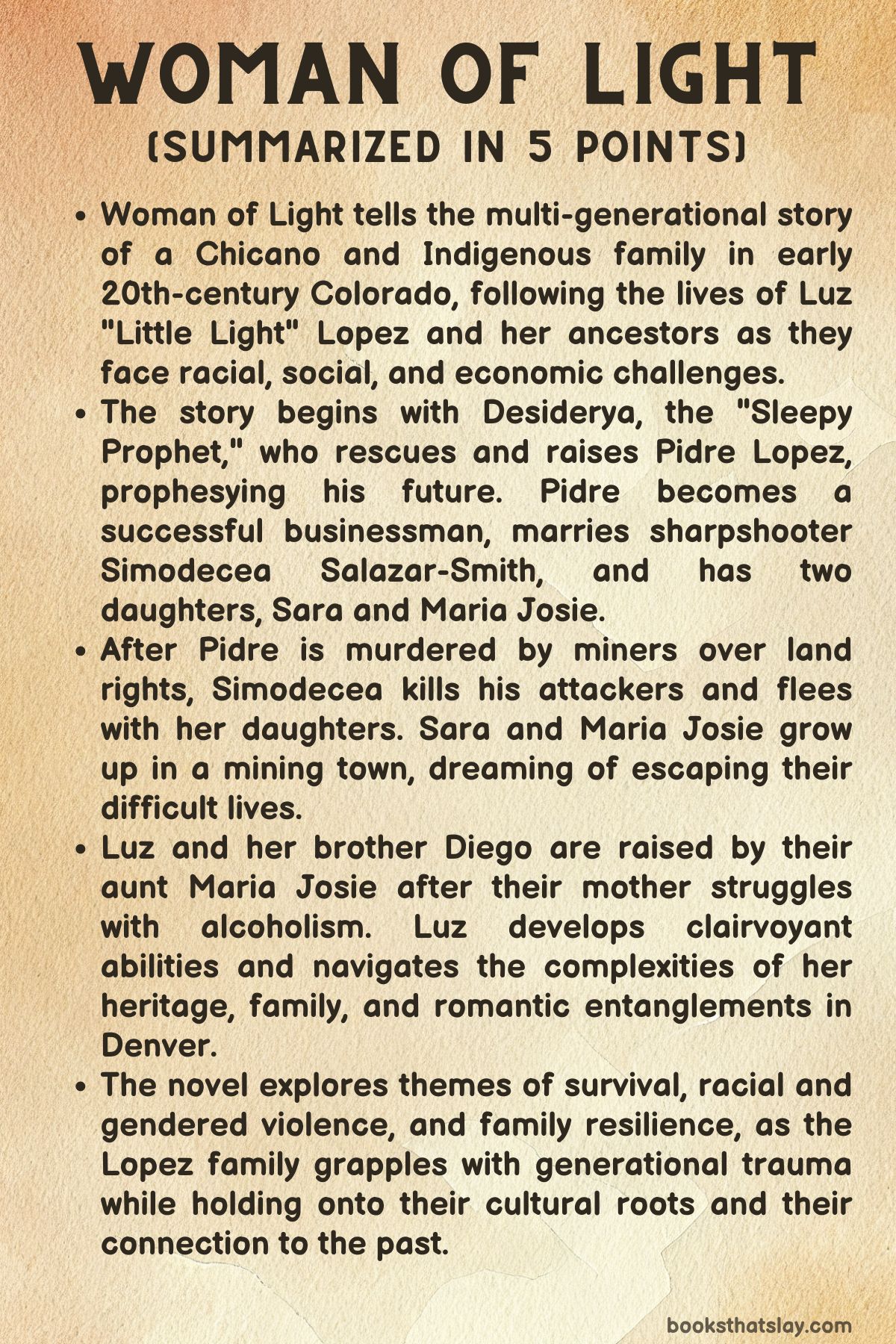

Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s Woman of Light is a multi-generational saga that blends historical realism with magical elements to explore the lives of an Indigenous Chicano family. Set primarily in early 20th-century Colorado, the novel follows Luz “Little Light” Lopez, a young woman with clairvoyant abilities passed down through her family, as she navigates the trials of her heritage.

Fajardo-Anstine interweaves themes of cultural survival, family resilience, and the challenges of navigating racial and gendered violence in America, creating a vivid portrait of a family whose strength is rooted in their shared past and enduring spirit.

Summary

The novel opens with Desiderya, known as the Sleepy Prophet, who receives a vision that leads her to rescue an infant, Pidre Lopez, from the wilderness. Desiderya raises Pidre in the village of Pardona, but before her death, she foretells his destiny: he will venture beyond the village, marry a strong woman, and father two daughters.

As a young man, Pidre leaves Pardona and finds success in southern Colorado as a businessman. In the town of Animas, he partners with Mickey, an English-literate man, to purchase land for a public amphitheater.

Pidre is captivated by Simodecea Salazar-Smith, a sharpshooter who accidentally killed her husband in a bear attack. He hires her for his show, and the two eventually fall in love and have two daughters, Sara and Maria Josie. Sara shows early signs of clairvoyance, while Maria Josie is headstrong and independent.

Trouble strikes when miners arrive in Animas, and Pidre’s land is seized due to a loophole in his ownership rights. When a violent confrontation leads to Pidre’s murder, Simodecea kills his attackers in self-defense. Fearing for her daughters’ safety, she flees with Sara and Maria Josie, but she is soon arrested.

The girls are taken in by kind locals in Saguarita, although they live apart due to financial constraints. As they grow older, they dream of escaping their limited circumstances.

Sara falls in with Benny, a hard-living man, and the two have two children, Diego and Luz. After Benny abandons the family, Sara sends her children to live with Maria Josie in Denver, where they find refuge in a cramped tenement. Luz, with her gift for reading tea leaves, begins to earn a reputation for her accurate fortunes, while Diego becomes a snake charmer and factory worker.

The novel explores the challenges the family faces in Denver, where Luz works in a laundry and assists David, a lawyer whose office is later targeted by the Ku Klux Klan.

As Luz grows into adulthood, she navigates complex relationships, including one with David and another with Avel, a musician who proposes to her. However, her budding romance with David leads to a painful rift with Avel, who, in his anger, sets fire to David’s law office.

As tensions rise, Luz calls for Diego’s return to Denver. Diego, who has been working in fields, answers her plea, only to confront more difficulties.

He discovers his father’s grave and takes responsibility for his child with Eleanor Anne, a woman he left behind.

Through these struggles, the family’s strength and bond are tested, but they remain anchored by their shared history and the resilience of their ancestors.

Characters

Luz “Little Light” Lopez

Luz, the central protagonist of Woman of Light, embodies resilience, vulnerability, and clairvoyant ability, representing a bridge between past and present generations.

As a descendant of Mexican, Pueblo, and European ancestry, she is steeped in the traditions of her diverse heritage. Her clairvoyance, passed down through her family, symbolizes her deep connection to her ancestral lineage.

Despite growing up in economic hardship, Luz maintains a hopeful outlook on life and a growing sense of independence.

The novel highlights her transition from childhood to young adulthood, as she navigates her identity, family responsibility, and romantic entanglements. Luz is a reflective character who quietly absorbs the struggles around her, trying to make sense of her role in a world marked by systemic oppression and personal losses.

Her attraction to David and the heartbreak with Avel marks her struggle with societal expectations and personal desires, ultimately pushing her toward self-realization.

As the novel progresses, Luz becomes more assertive, coming into her own and setting the stage for her transformation into a more self-aware and independent woman.

Pidre Lopez

Pidre is Luz’s grandfather, and his storyline shapes the novel’s historical and emotional foundation.

Raised by the Sleepy Prophet Desiderya, Pidre is tied to a mystical origin, being a child of prophecy, and embodies a blend of spiritual and practical traits.

His rise as a successful businessman in the mining town of Animas speaks to his ambition and adaptability in a world undergoing industrial transformation.

His partnership with Mickey, who can read English, underscores the systemic barriers faced by non-English-speaking communities during this time. Pidre’s love affair with sharpshooter Simodecea Salazar-Smith introduces a romantic yet tragic aspect of his life.

Their union blends Mexican, Pueblo, and European cultural traditions, but their world collapses when Pidre is murdered by men seeking to take his land. His death catalyzes the family’s fragmentation and ongoing struggle for survival, highlighting themes of land dispossession and racial violence.

Simodecea Salazar-Smith

Simodecea, Pidre’s wife and the matriarch of the Lopez family, is a character shaped by strength, resilience, and tragedy.

A sharpshooter who accidentally killed her husband during a performance, she carries the burden of her past into her relationship with Pidre.

Her marriage to him offers her a second chance at love, and together they build a family and a thriving business. However, when Pidre is murdered, Simodecea takes the path of a protector, killing his attackers in a moment of fierce retaliation.

Her decision to flee with her daughters Sara and Maria Josie symbolizes the survival instinct embedded in her character. Simodecea’s fate remains somewhat ambiguous, as she disappears after instructing her daughters to run.

She represents a form of defiant resistance against oppressive forces and embodies a maternal figure willing to do whatever it takes to protect her family.

Sara and Maria Josie Lopez

Sara and Maria Josie, Pidre and Simodecea’s daughters, represent two contrasting aspects of personality and survival. Sara, the older sister, is depicted as compliant and sensitive, inheriting the family’s clairvoyant gift.

Her character is marked by a sense of duty and responsibility, though she succumbs to the influence of Benny, with whom she has two children, Diego and Luz.

Her eventual struggle with alcoholism reflects her emotional vulnerability and inability to cope with the weight of her responsibilities. In contrast, Maria Josie is independent, rebellious, and determined to carve out her own path. Her adventuresome spirit leads her away from the traditional roles expected of women during the time.

Her pregnancy and subsequent abortion at the hands of a German doctor symbolize the physical and emotional violations she endures as a woman of color.

Maria Josie’s decision to walk to Denver signifies her relentless pursuit of a new life, where she ultimately becomes a crucial figure in the upbringing of her niece and nephew.

Together, Sara and Maria Josie represent the divergent ways women in the novel cope with their traumatic pasts and oppressive environments.

Diego Lopez

Diego, the son of Sara and Benny, is portrayed as a charismatic and adventurous young man who embodies both masculine strength and vulnerability. Working in a rubber factory and performing as a snake charmer, Diego tries to balance his role as a provider with his personal desires.

His romantic entanglements with multiple women, including Eleanor Anne, a white woman whose family violently opposes their relationship, underscore the racial tensions of the time.

The attack on Diego by Eleanor Anne’s family signifies the brutal consequences of interracial relationships, and his departure from Denver mirrors his father’s earlier abandonment. Diego’s return to Denver at Luz’s request and his discovery of his father’s grave symbolize his reconnection with family roots, while his retrieval of his infant daughter Lucille signals a potential shift toward responsibility and maturity.

Diego’s character arc demonstrates the struggle of a man caught between individual freedom and familial duty.

David Tikas

David is a Greek-American lawyer who represents an intersection of racial and class dynamics in the novel. As Luz’s employer and eventual lover, he is a complex character with ambiguous motivations. His work in defending marginalized people against legal and social injustices contrasts with his personal actions, particularly his sexual advances toward Luz.

The episode in the office where the Ku Klux Klan breaks in highlights his precarious position as a non-white person in a predominantly white society, yet his exploitation of Luz’s affection reveals his own shortcomings. David’s relationship with Luz is one of power imbalance, where his status as a lawyer and Luz’s subordinate position create ethical tensions.

By the end of the novel, Luz’s decision to leave David behind signifies her reclaiming of agency, while David’s law office burning down symbolizes the crumbling of his influence in her life.

Avel Cosme

Avel is Luz’s first boyfriend and represents the conventional expectations of love and marriage for a young woman like Luz.

Avel is depicted as passionate and deeply in love with Luz, which contrasts with Luz’s more ambivalent feelings toward him. His proposal of marriage reveals his desire for stability and tradition, though Luz’s reluctance signals her desire for freedom and independence.

Avel’s heartbreak over Luz’s affair with David leads him to destructive behavior, culminating in the arson of David’s law office.

This act of violence marks Avel’s inability to cope with his sense of betrayal, and his actions contrast with Luz’s growing sense of personal agency. Avel’s arc in the novel highlights the dangerous consequences of unrequited love and possessiveness, particularly in the context of young, working-class men.

Lizette and Teresita

Lizette, Luz’s cousin, plays a significant role in Luz’s coming-of-age story. A more grounded and practical character, Lizette is engaged to Alfonso, and her plans for marriage provide a contrast to Luz’s more uncertain romantic life.

Lizette’s role as a seamstress and her determination to have a grand wedding symbolize her aspirations for stability and upward mobility within the constraints of her social environment.

Teresita, Lizette’s mother, is a nurturing figure who cares for Diego after his assault and provides a maternal presence in the story. Both women represent the strong network of familial support that surrounds Luz, even as they navigate their own struggles within a racist and patriarchal society.

Themes

Intergenerational Trauma and the Persistence of Memory

Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s Woman of Light intricately explores the theme of intergenerational trauma, examining how the pain and violence experienced by past generations reverberate through time, shaping the lives of descendants.

The novel spans multiple generations, tracing the ancestral lineage of Luz Lopez and her family, highlighting how the injustices faced by Pidre Lopez and Simodecea Salazar-Smith—whether from racial violence, land dispossession, or the brutal consequences of industrialization—continue to impact later generations.

The deaths of patriarchal figures like Pidre and the subsequent struggles faced by his daughters Sara and Maria Josie reflect a traumatic legacy that is inherited rather than experienced first-hand by their children.

Luz’s clairvoyance, a supernatural gift passed down through the family, symbolizes not just a literal connection to the past but also a metaphorical one: the weight of ancestral suffering and resilience is carried by Luz, forcing her to navigate a world shaped by the unhealed wounds of history.

This interweaving of historical violence and familial memory highlights how trauma is a cyclical force that spans generations, shaping identities and limiting opportunities.

Intersectionality of Gender, Race, and Class-Based Oppression

The novel deftly handles the intersectionality of identity, showing how different forms of oppression—gender, race, and class—are interlinked and compounded for marginalized individuals. Luz and the women in her family face a multitude of challenges rooted in their identities as women of color living in early 20th-century America.

The Lopez women not only endure racial violence and systemic discrimination as Mexicans and Indigenous people but also bear the additional weight of patriarchal structures that reduce their economic and social agency. For instance, Simodecea’s battle for land rights becomes a fight for survival in a world where both legal systems and corporate greed, driven by patriarchal capitalism, conspire against her family.

Moreover, as Luz navigates her own coming of age, she is forced to confront the limited economic opportunities available to women like her, as seen in her menial job at the laundry. The sexual violence Luz witnesses and experiences, particularly her coerced encounter with David, underscores how patriarchal power manifests in intimate, insidious ways.

In this sense, the novel articulates a complex understanding of how identity is not fragmented into categories but experienced holistically, with each layer of oppression feeding into and amplifying the other.

Cultural Displacement and the Loss of Indigenous Identity

Cultural displacement emerges as a critical theme, explored through the family’s separation from their Pueblo roots and the broader loss of Indigenous identity in the face of colonial violence.

From the destruction of Pardona to the displacement caused by industrial expansion and capitalist exploitation, the Lopez family’s connection to their ancestral land and culture is systematically eroded. Pidre’s return to Pardona to find it vanished symbolizes the erasure of Indigenous histories and ways of life under the pressure of colonization.

This cultural loss is not simply geographic but spiritual and existential, as the Lopez family becomes further removed from their origins. Luz’s inherited clairvoyance offers a link to the old ways, but it is a fragile one, easily overshadowed by the demands of survival in a world increasingly defined by industrialization and white settler dominance.

The theme of cultural displacement is also explored through language and community, as the characters, particularly Luz and Diego, struggle to navigate an identity that is fragmented and vulnerable to assimilation.

The tension between maintaining cultural heritage and the necessity of adapting to a hostile, rapidly modernizing world underscores the tragic consequences of colonialism for Indigenous and mixed-heritage families.

The Gendered Legacy of Economic Disenfranchisement in Migrant Communities

Economic disenfranchisement, as explored through the lives of the Lopez women, reflects the gendered dimensions of poverty and labor exploitation in migrant communities.

Throughout the novel, women like Maria Josie, Sara, and Luz are forced into menial labor positions—laundresses, seamstresses, and domestic workers—reflecting the lack of economic mobility available to them.

The novel places significant emphasis on the ways in which the American economic system devalues the labor of women of color, forcing them into positions of precarity.

The character of Luz, whose clairvoyant abilities grant her a symbolic connection to something greater than herself, is nevertheless constrained by the harsh economic realities of her life. Her attempts to secure a better future, particularly through her relationship with David, ultimately underscore how even upward mobility comes with severe moral and personal compromises for women like her.

Furthermore, the economic struggle is intertwined with racial exploitation, as Luz and Lizette work for white employers who benefit from their labor while systematically dehumanizing them. This theme is not only about economic survival but also about how the characters attempt to reclaim agency within a system designed to keep them in positions of dependency and subordination.

The Role of Community in Navigating Oppression and Finding Resilience

Another profound theme is the role of community as a means of survival and resilience in the face of systemic oppression.

Despite the isolating and oppressive forces surrounding them, the Lopez family continually finds strength and solidarity in their community ties, whether through blood relations or extended kinship networks.

Luz and Diego’s relationships with their distant cousins, like Lizette and her parents, offer moments of respite from the harsh realities they face in Denver’s tenements. Even as Luz is exploited by David, she finds solace and purpose in her role within the broader community, participating in activism and cultural preservation.

The community also provides a buffer against the racial violence perpetrated by outsiders, such as the attack on Diego by Eleanor Anne’s family. Moreover, the novel portrays community not just as a passive shelter but as an active space of resistance where individuals come together to push back against the injustices they face.

From Teresita’s healing practices to the communal efforts to hide and protect vulnerable individuals, community in Woman of Light is both a source of resilience and a defiance of the isolation imposed by racist and capitalist structures.

This theme emphasizes that while individual struggles are significant, collective action and shared cultural identity provide a necessary foundation for survival and resistance.

The Duality of Modernity and Tradition in the Mexican-American Experience

Woman of Light explores the tension between modernity and tradition within the Mexican-American experience, particularly as the characters grapple with the pressure to assimilate into an increasingly industrial and racially segregated society.

This duality is most clearly embodied in Luz, whose clairvoyance represents a connection to ancestral wisdom and Indigenous spirituality, while her involvement in modern Denver—working with David and navigating urban life—forces her to confront the encroaching demands of modernity.

The novel continually juxtaposes the traditional values and customs of the Lopez family with the realities of industrialization, cultural assimilation, and economic modernization.

Pidre’s entrepreneurial ventures and his tragic fall signal the broader theme of how modernity can both provide opportunities and bring destruction to those who are unprepared or marginalized within its systems.

Similarly, Luz’s journey is marked by the struggle to maintain her sense of self and family identity while being drawn into the modern world’s alienating structures.

The characters are caught between two worlds—one that values communal identity, tradition, and ancestral connection, and another that demands individualism, material success, and assimilation.

This tension reflects the broader experience of Mexican-American communities navigating their cultural heritage while adapting to the demands of an often-hostile modern world.