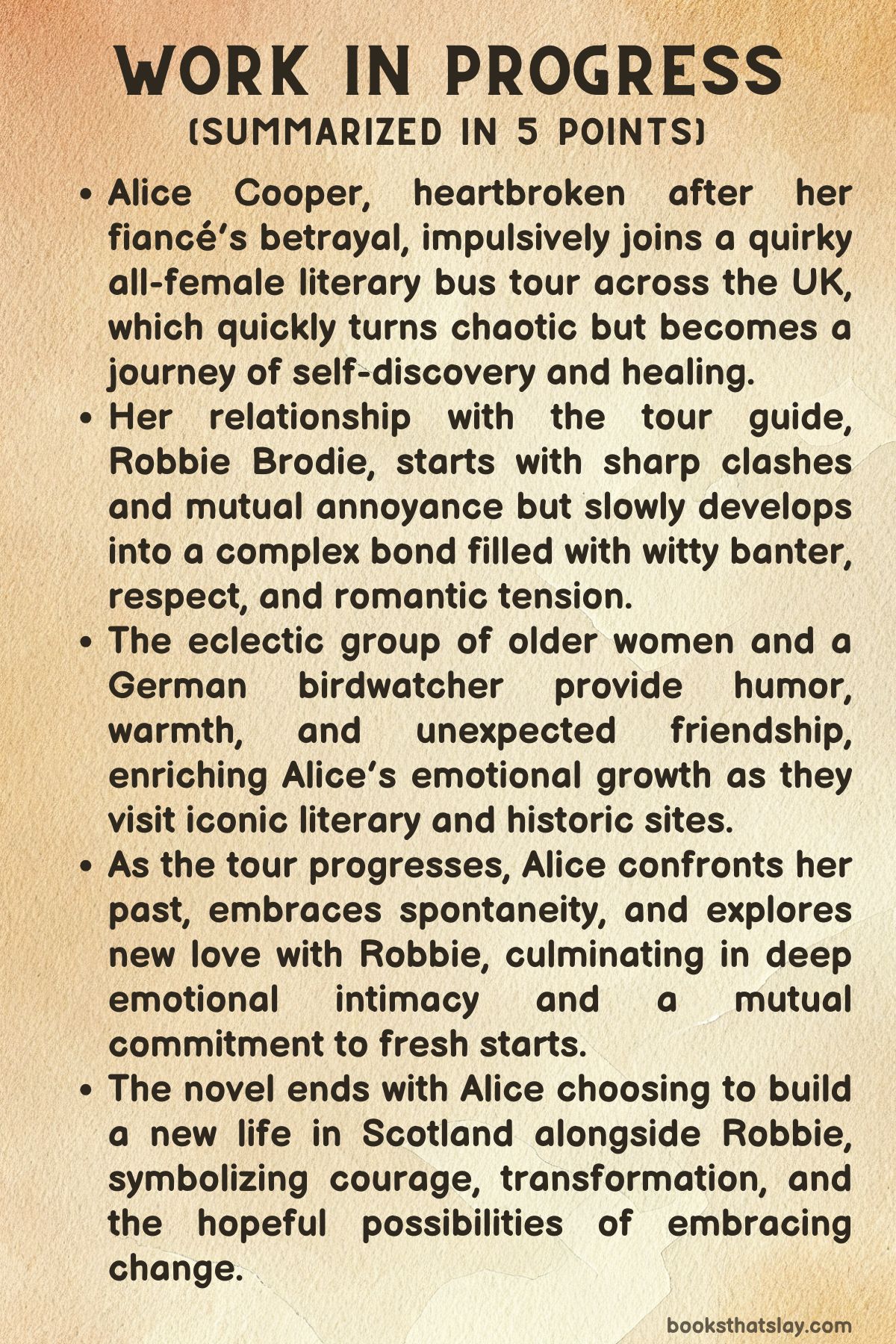

Work in Progress Summary, Characters and Themes

Work in Progress by Kat Mackenzie is a contemporary romantic comedy about rebuilding, rediscovering, and reclaiming a sense of self after heartbreak. Set against the richly atmospheric backdrop of a literary tour across the United Kingdom, the novel follows Alice Cooper, a thirty-something Bostonian who impulsively books a group bus tour after a painful breakup and professional burnout.

What she expects is healing solitude and poetic landscapes—what she gets instead is a cranky Scottish guide, a bus full of eccentric older women, and an unpredictable emotional rollercoaster. With sharp humor, messy vulnerability, and moments of unexpected grace, the story captures the hilarity and hardship of starting over, especially when the past won’t let go and the future insists on arriving in the form of the most infuriating man imaginable.

Summary

Alice Cooper’s grand plan for healing begins in spectacular chaos. After enduring an excruciating 36-hour journey filled with flight delays and exhaustion, she arrives in Scotland only to discover that her supposedly indestructible suitcase has been crushed.

Her first interaction with Robbie—the infuriatingly smug Scottish man at the airport—leaves her seething. When she later finds out he’s actually the driver and guide of her three-week literary bus tour, her horror is complete.

Instead of the youthful, adventurous crowd she imagined, Alice finds herself stuck with a group of lively, quirky older women, including the sharp-witted Helena, dramatic Flossie, and blunt Agatha.

From the outset, Alice and Robbie butt heads. She is fiery and sarcastic, while he remains unflappably calm and maddeningly teasing.

Their verbal sparring becomes a constant undercurrent of the trip, even as Robbie proves himself to be both knowledgeable and kind. As the group journeys through literary landmarks—from Rosslyn Chapel to the Brontë moors to Whitby’s Gothic coast—Alice begins to soften.

The older women surprise her with their vibrance and acceptance. The tour’s historical richness and scenic wonder slowly reconnect her to the parts of herself she thought were lost.

Yet Alice’s emotional wounds remain raw. She’s recovering from the sudden engagement of her ex-fiancé, a discovery she made via Instagram.

She’s also grappling with the collapse of her career and a nagging sense of failure. Her misadventures—like battling a baffling British shower or vomiting on a bus after a night of drinking—are steeped in both hilarity and humiliation.

But they also expose her vulnerability, making room for genuine connection.

One such moment arrives during the Whitby Goth Weekend. Dressed in costume and high on cocktails, Alice feels alive—until a drunken meltdown in a pub bathroom cracks her polished facade.

Helena finds her, offering comfort and understanding. Later, when Alice injures herself and needs help undressing, it’s Robbie who cares for her with gentleness and restraint.

A new tenderness emerges between them, laden with unspoken feelings.

Still, Alice is shaken to learn Robbie has a girlfriend—Isla. Trying to maintain dignity, she brushes off the intimacy they’ve shared.

Meanwhile, Helena tries matchmaking, introducing Alice to her Oxford-based son, Tristan. Expecting awkwardness, Alice is surprised by Tristan’s charm and grace.

During their time in Oxford, Tristan becomes a calm, sweet counterpoint to Robbie’s chaotic magnetism. Robbie, however, grows visibly unsettled, revealing his jealousy despite his relationship status.

A formal dinner with Tristan and a moonlit kiss offer Alice brief contentment, but her heart remains divided. Robbie’s apology and his offer of friendship sting—especially as their camaraderie deepens during a wild charity shopping spree and a quiet conversation over tea.

There, Robbie reveals the emotional scars of his mother’s death and the way grief reshaped his life. Alice shares her own heartbreak, and they forge an unspoken emotional intimacy.

But reality looms. Isla is waiting.

Alice, determined to stay grounded, prepares herself to meet her. Meanwhile, her creative spark begins to return—her photography thrives, and her confidence grows.

She starts to believe in the possibility of a new beginning.

As the tour reaches its final days, a pivotal discovery shocks the group: Flossie and Sidney, their elderly companions, are revealed to be former lovers. Their secret history of circus life and youthful romance stuns everyone, especially Agatha.

Flossie’s story of passion cut short by circumstance resonates deeply with Alice and Robbie. To Robbie, it’s a tragedy; to Alice, it’s proof that risking love is always worth it, even if it ends.

Their emotional responses to this story expose their differing worldviews. Robbie fears loss.

Alice begins to see the beauty in impermanence. When the group returns to Edinburgh for their final stop, emotions run high.

Robbie gives a touching farewell speech. Alice, heart aching, spends one last night with him—full of tenderness and longing—but chooses to leave.

She needs to face her life, rebuild it, and figure out who she is without anyone’s shadow.

Back in Boston, Alice throws herself into a new routine: she lands a job at an NGO, reconnects with friends, and dates Tristan casually. But she can’t shake the feeling of absence.

Letters and emails from Robbie sustain a thread of connection, while regular chats with Helena and the other women keep the spirit of the tour alive.

One day, Helena visits and prompts Alice into a spontaneous photoshoot that captures the joy and freedom she’d begun to rediscover. It becomes a moment of clarity.

Alice realizes she isn’t finished. She still wants adventure, risk, and love.

She applies for a UK Ancestry visa.

The story comes full circle when Alice flies back to Scotland. She surprises Robbie at the airport with a bold declaration of love and a plan to stay.

It’s not just about rekindling a romance—it’s about reclaiming her agency and choosing a life of meaning and movement. In Robbie’s shocked joy, she finds her answer.

Work in Progress ends not with a fairy-tale resolution but with a sense of possibility. Alice has transformed—not by finding a man, but by finding herself.

And the love she chooses is not just for someone else, but for the uncertain, beautiful life ahead.

Characters

Alice Cooper

Alice Cooper, the protagonist of Work in Progress by Kat Mackenzie, is a dynamic and deeply relatable character whose journey of self-reinvention drives the emotional core of the novel. Introduced as a woman reeling from heartbreak and professional collapse, Alice initially seeks solace and distraction through a spontaneous literary tour of the UK.

Her emotional state is reflected in her chaotic experiences—missed flights, destroyed luggage, and the humiliating encounter with the unflappable tour guide, Robbie. Despite these setbacks, Alice is persistent, fiercely independent, and possessed of a sharp wit that fuels her combative banter with Robbie.

Her vulnerability often simmers beneath the surface of her sarcasm, and as the tour unfolds, layers of her personality are peeled back. Alice’s emotional evolution—from someone in survival mode to a woman embracing possibility—is mirrored in her growing affection for the quirky elderly women on the tour, her rekindled interest in photography, and her tentatively reawakening sense of self-worth.

Her relationship with Robbie, marked by antagonism, tenderness, and unspoken longing, challenges her notions of love and fear. By the novel’s end, Alice’s decision to return to Scotland and choose joy over safety marks a triumphant reclaiming of agency, proving that her story is not just one of romance, but of courage and transformation.

Robbie

Robbie, the Scottish tour guide who initially antagonizes Alice, evolves into a complex, multifaceted character whose stoicism hides deep emotional wounds. At first glance, he is smug, sarcastic, and maddeningly calm in the face of Alice’s indignation, but it quickly becomes apparent that his sharp tongue is a defense mechanism as much as Alice’s is.

As the story progresses, Robbie reveals a quieter, more tender nature—particularly in moments where he cares for Alice during her physical and emotional breakdowns. His backstory, involving the loss of his mother and the creation of his tour company as a means of coping with grief, humanizes him profoundly.

He’s a man who has rebuilt his life from ashes and carries the weight of that pain with quiet dignity. His connection with Alice forces him to confront vulnerabilities he has long kept at bay, and his conflicting actions—offering comfort, expressing protectiveness, but being tethered to a girlfriend—illustrate his own confusion and guarded heart.

Robbie’s final plea for Alice to stay, followed by his stunned joy at her return, cements him as a man who, while emotionally reticent, ultimately chooses love and healing when it’s finally offered to him.

Helena

Helena emerges as the heart of the supporting cast—a wise, warm, and quietly formidable woman whose life story becomes a crucial turning point for Alice. She defies expectations of the elderly tourist archetype with her wit, compassion, and a resilience forged through personal tragedy.

When Alice spirals into a drunken, grief-induced meltdown, Helena is the one who provides not only physical aid but maternal emotional support, offering grace rather than judgment. Her backstory—marked by loss, reinvention, and unexpected happiness as a mother and businesswoman—serves as a mirror to Alice’s own fears and aspirations.

Helena becomes a symbol of the beauty that can arise from life’s detours. She’s not merely a side character; she’s a guide, mentor, and friend whose presence catalyzes Alice’s internal transformation.

Her continued presence in Alice’s life even after the tour, including her spontaneous visit to Boston and the empowering photo shoot, reinforces the novel’s message about the lasting impact of chosen community and intergenerational solidarity.

Tristan

Tristan, Helena’s Oxford-educated son, serves as both romantic distraction and contrast to Robbie. Handsome, refined, and effortlessly charming, Tristan initially seems like a too-good-to-be-true match for Alice.

He is respectful, gracious, and genuinely interested in showing her kindness—qualities that highlight the emotional turmoil Alice feels as she wrestles with her feelings for Robbie. Tristan represents a safe and appealing possibility, but one that lacks the emotional spark and shared history she has with Robbie.

Their kiss is tender, their evening lovely, but the relationship lacks the depth that Alice’s connection with Robbie has cultivated. Still, Tristan is never portrayed as a villain or obstacle; rather, he functions as a mirror, helping Alice see what she truly wants and deserves.

His inclusion in the narrative also deepens Helena’s character, offering a glimpse into her family life and reinforcing the theme of unexpected paths leading to love and fulfillment.

Flossie and Sidney

Flossie and Sidney’s late-blooming love story, revealed in a moment of near-cinematic drama, becomes a poignant subplot that adds emotional richness to the novel. Flossie, known throughout the tour for her eccentricities and flair, is revealed to have once been a circus performer deeply in love with Sidney.

Their secret romance—separated by familial obligation and societal expectations—is a reminder of the many lives people live beneath the surface. Sidney’s reappearance and their emotional reunion ignite a conversation among the group about lost opportunities, the passage of time, and the power of memory.

For Alice, Flossie and Sidney’s story becomes a source of inspiration rather than sorrow. She envies the passion they once had and the boldness with which they embraced it, however fleetingly.

Their narrative serves as both a cautionary tale and a celebration of risk-taking, reinforcing Alice’s decision to pursue a life shaped by courage and authenticity.

Agatha

Agatha, often the voice of pragmatism in the tour group, initially reacts with confusion and judgment to Flossie’s revelation. Her role is more understated than Helena’s or Flossie’s, but no less significant.

She represents the traditional path—stable, sensible, perhaps a bit emotionally guarded. Yet as the story unfolds, Agatha’s respect for her fellow travelers grows, and she begins to reveal a more open-minded and empathetic side.

Her arc complements the broader theme of the story: that even those who appear fixed in their ways can evolve, surprise, and form meaningful bonds. Agatha’s growing affection for her companions, especially during the final scenes in Edinburgh, helps illustrate the subtle but powerful shifts that occur within the group dynamic.

Themes

Emotional Recovery and Self-Renewal

Alice’s story in Work in Progress is anchored in the raw and erratic path of healing after profound emotional upheaval. Her life has collapsed in several ways—romantic betrayal, professional burnout, and the erosion of self-worth.

Rather than curling inward, she makes the impulsive but life-affirming decision to fly to the UK, clinging to the hope that geography might offer clarity. The tour becomes a mirror for her inner disarray: her suitcase is destroyed, the plumbing is nonsensical, she’s surrounded by strangers, and even her guide is the same man who initially aggravated her at the airport.

In many ways, this discomfort is not incidental but central to her transformation. The inability to control her environment forces her to adapt, to drop expectations, and to allow experience to shape her anew.

This emotional recovery is not linear. She stumbles—quite literally with twisted ankles, broken showers, and humiliating hangovers—but each misstep contributes to the reshaping of her identity.

Her connections with the older women on the tour, especially Helena, serve as emotional stabilizers. Helena offers not just sympathy but wisdom carved from her own scars.

Their conversations show Alice the long view—that a life can reroute and still be fulfilling. Through humor, kindness, embarrassment, and shared vulnerability, Alice begins to find herself again, not by pretending the pain didn’t happen, but by building a different future with those broken pieces.

Her eventual return to Scotland is less about rekindling romance and more about claiming a life she now feels worthy of designing, shaped by self-compassion and reclaimed agency.

Romantic Misdirection and Emotional Maturity

The romantic arc between Alice and Robbie functions not simply as a will-they-won’t-they trope but as a lens through which emotional maturity is tested and cultivated. Their dynamic is full of friction: verbal sparring, stubborn pride, and playful antagonism.

Yet beneath the banter lies vulnerability. Both carry emotional baggage—Alice with her recent heartbreak, Robbie with his grief and guilt over his mother’s death and the upheaval it caused in his life.

These emotional backstories prevent them from immediately recognizing or admitting their connection. The presence of other romantic possibilities, like Isla and Tristan, further clouds the emotional waters.

Instead of serving as mere obstacles, these other relationships help Alice and Robbie gain clarity. Tristan is kind and attractive, but his purpose becomes evident not as a soulmate but as a mirror, helping Alice realize that affection and compatibility aren’t always enough when something deeper is missing.

Robbie’s girlfriend Isla, meanwhile, adds moral complexity to Alice’s feelings. Rather than collapsing into the archetype of the “other woman,” Alice chooses restraint.

She doesn’t force Robbie’s hand or manipulate events in her favor. This restraint is significant.

The more she desires him, the more she also demands honesty—from him and from herself. Their eventual union is not a product of reckless desire but of hard-won self-awareness.

When she chooses to leave Robbie at the end of the tour, it’s not a rejection of love but a prioritization of self. The decision to return later, on her own terms, becomes a declaration not just of love but of personal readiness.

The romantic resolution, while emotionally satisfying, is grounded in maturity rather than fantasy.

Female Friendship and Intergenerational Solidarity

What begins as a disappointment—being surrounded by elderly women instead of fellow young travelers—evolves into one of the most grounding and transformative elements of Alice’s journey. These women are not caricatures but deeply textured individuals, each with a personal history, emotional complexity, and quiet wisdom.

Through shared meals, mishaps, confessions, and emotional support, Alice experiences the stabilizing power of female friendship across generations. Helena, in particular, becomes a mentor figure, her life story reframing Alice’s view of what fulfillment can look like.

A career interrupted by tragedy did not lead to lifelong regret but opened the path to a different, meaningful life filled with motherhood, community, and purpose.

The Flossie and Sidney subplot is another expression of intergenerational richness. Their circus romance, once buried under decades of silence, becomes a catalyst for reflection—not just for Flossie and Agatha but for Alice and Robbie as well.

The older women, while sometimes eccentric or baffling, operate as emotional anchors. They offer perspective without preaching, laughter without mockery, and presence without pressure.

These friendships become a counterpoint to the isolation Alice felt in Boston after her breakup. She learns that solidarity and sisterhood can bloom in the most unexpected of places, and that age doesn’t diminish relevance, agency, or beauty.

The support she receives is not just comforting but formative. It teaches her how to be seen again—by others and by herself.

Embracing Risk and Redefining Adventure

The theme of risk is intricately tied to Alice’s emotional evolution. Her entire journey begins with a bold, if impulsive, decision to escape her crumbling life by flying to a different continent.

This act alone sets a precedent: sometimes stepping into the unknown is not reckless, but necessary. Throughout the tour, she is repeatedly faced with decisions that force her to relinquish control, comfort, and certainty.

Whether it’s dressing in goth regalia at Whitby, drunkenly trusting Robbie to care for her after an injury, or braving a conversation about her emotional collapse with a near-stranger, each instance reinforces that emotional growth is born from moments of vulnerability and risk.

Flossie and Sidney’s story becomes a thematic lighthouse. Their youthful rebellion, though thwarted, was an act of love and courage.

Alice is deeply moved by their past, realizing that regret doesn’t stem from taking risks, but from avoiding them. The tour itself is full of moments that challenge her—both comic and sincere—each demanding she take a small leap toward a more authentic life.

The final act of returning to Scotland, not as a tourist but as someone ready to stay, represents the culmination of this thematic arc. She’s no longer running from her pain but running toward possibility.

Risk, for Alice, evolves from something terrifying to something sacred—a gateway to transformation. Her leap is not just about romance, but about choosing a life that requires courage, resilience, and hope.

Identity Reconstruction and Creative Purpose

Alice’s identity crisis is multi-layered. She is not only grappling with romantic betrayal but with the implosion of a life she carefully built.

Her job loss is not just professional but existential—stripping her of structure, purpose, and confidence. Photography becomes an early thread that hints at her creative instinct, but it isn’t until she begins to use her camera more actively that her rediscovery takes on momentum.

The landscapes, historical sites, and quirky tour moments provide both metaphor and medium for creative revival. Photography is no longer a passive skill but a way of reclaiming authorship over how she sees the world—and herself.

Conversations with others—Robbie, Helena, the women on the tour—help reflect back to her the aspects of herself she had buried under failure. She begins to write again, to imagine again, and to visualize a life beyond what she had previously assumed was the endgame.

This journey is less about finding a new career path and more about unearthing dormant passions. Creative purpose becomes a form of self-respect: a refusal to disappear.

By the time she applies for the ancestry visa, Alice isn’t chasing a man; she’s chasing a version of herself who is not afraid to live by design rather than default. The reconstruction of identity in Work in Progress is about more than healing; it’s about choosing to be the protagonist in her own narrative.