You Dreamed of Empires Summary, Characters and Themes

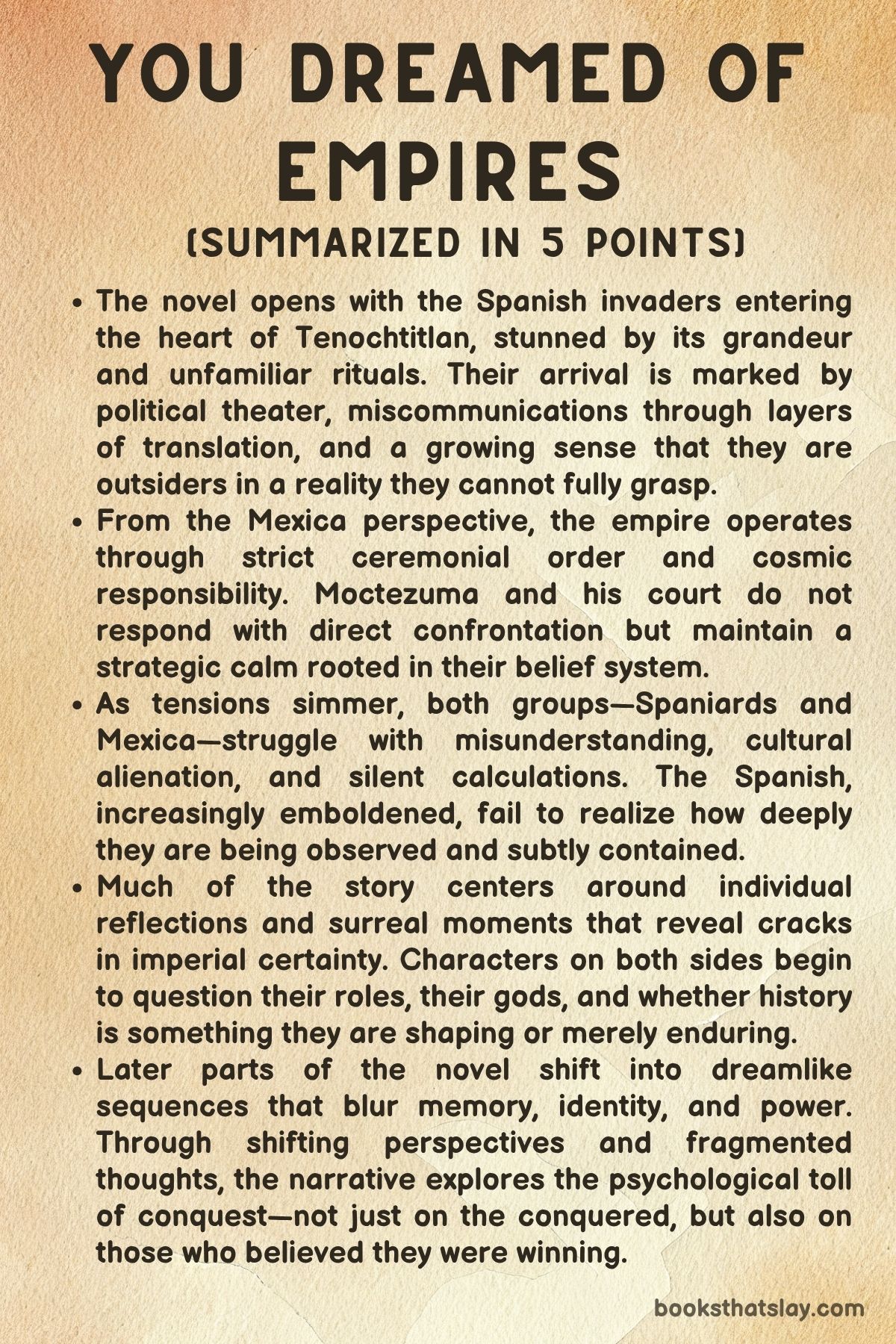

You Dreamed of Empires by Álvaro Enrigue is a darkly imaginative historical novel that reimagines the final days before the fall of the Mexica (Aztec) Empire through a surreal and politically charged lens. Blending real historical figures with a fictional Spanish captain named Jazmín Caldera, Enrigue reconstructs the confrontation between Hernán Cortés and Moctezuma not as a simple tale of conquest but as a hallucinatory unraveling of civilizations.

The book excavates the psychological and spiritual disintegration of both Spanish invaders and Mexica rulers, capturing their misunderstandings, internal conflicts, and descent into ritual, paranoia, and power games. Rich with satire, philosophical insight, and stylistic boldness, it turns history into a fever dream of imperial collapse.

Summary

You Dreamed of Empires opens in the opulent yet menacing palace of Tenochtitlan, where Captain Jazmín Caldera, a Spanish emissary, is seated beside two Aztec priests whose grotesque appearance and odor evoke the violence underpinning Mexica ritual. As he hesitates to eat the ceremonial food, the tension at the table underscores the larger fragility of Spanish-Mexica diplomacy.

Hernán Cortés, watching closely, expects obedience from his men, while Princess Atotoxtli disrupts the façade with sharp intelligence and political cunning. Her pointed inquiry about the Tlaxcalteca army forces Caldera into a moment of truth-telling, triggering both Cortés’s praise and her fury.

She storms off to confront Moctezuma, exposing their strained marriage, her displacement from royal chambers, and his disconnection from leadership.

The emperor, isolated and brooding, increasingly withdraws into magical mushrooms and visions, treating political crisis with indifference. Meanwhile, Caldera and other Spaniards begin to suspect they are trapped in a gilded cage.

The palace’s symmetrical corridors become a psychological maze, echoing their entrapment. The grandeur, the intoxicating meals, and the absence of overt hostility create an uneasy calm.

Caldera, Luengas, and Vidal lose themselves in the halls, unable to orient themselves without the scent of chocolate guiding them. Moctezuma, meanwhile, coldly condemns a young servant—his own niece—to death, displaying the moral erosion at the heart of the empire.

The narrative expands to the eerie quiet of Axayacatl’s palace, where Spanish soldiers, artisans, and slaves attempt to navigate its labyrinthine halls. Despite its emptiness, servants seem to operate behind invisible curtains.

As Caldera and others encounter each other in their aimless wanderings, the palace appears both alive and unknowable. On the roof, Caldera concludes they are being watched, neither guarded nor welcomed—a dangerous ambiguity.

Below, Badillo tends to horses in an idyllic orchard, oblivious to the impending chaos.

Moctezuma, secluded and surrounded by his inner circle, rambles cryptically about fate and war, revealing a mind slipping from pragmatism to fatalism. His advisers—chief among them Tlilpotonqui—struggle to maintain cohesion.

Tlilpotonqui, once close to the emperor, now finds himself sidelined and increasingly paranoid. He fails to interpret the shifting political terrain, even as Atotoxtli and their son, Tlacaelel, assume more control.

Atotoxtli, the clearest strategist, sees the Spanish as unknowable agents of disruption and aims to manipulate internal divisions to preserve Mexica dominance. She considers letting the Tlaxcalteca destroy Texcoco in a proxy conflict that could strengthen the empire’s position.

Parallel narratives provide more intimate snapshots of power and identity. Aguilar, a former friar turned translator, instructs Caldera in wearing native clothing, a moment that blurs cultural boundaries and mocks Spanish superiority.

Malinalli, Cortés’s interpreter and concubine, navigates the treacherous dynamics of language and loyalty. At once indispensable and abused, she becomes a symbol of how women are used and maneuvered within colonial systems, yet also agents of survival and subversion.

The novel reaches a pivotal moment as Cortés leads his men to the Templo Mayor, intending to assert Spanish religious dominance. Their awe at the scale and sacredness of the temple momentarily checks their arrogance.

Ignoring Aguilar’s counsel to wait, Cortés advances, unleashing a surreal sequence of events. Moctezuma, drugged and dissociated, takes a subterranean path to ascend the temple.

While he detaches from the material world, his empire drifts into irrelevance.

In a parallel scene of symbolic encounter, Atotoxtli approaches Malinalli not as an enemy but as a fellow woman navigating treacherous power structures. Their conversation is cautious but slowly transforms into one of strategic understanding.

Atotoxtli offers Malinalli a role within the imperial court, tempting her to defect. Their joint visit to the horses becomes a moment of mutual revelation: to Atotoxtli, the cahuayos represent a military future the Mexica could appropriate.

Meanwhile, Caldera explores Tenochtitlan’s bustling streets, awed by its beauty and organization. He sees in the tzompantli not savagery but a profound philosophy of mortality.

His quiet departure from the Spanish party, possibly arranged by Atotoxtli, hints at his ideological shift.

At the temple, the Spaniards are confronted by the realities of human sacrifice. The horror disrupts their bravado; even Cortés is internally shaken.

Aguilar observes with contempt, aware of the chasm that separates the two civilizations. As Moctezuma prepares for a formal meeting with Cortés, elaborate ceremonial protocols are described, symbolizing the rigidity and theatricality of power.

During the audience, Moctezuma invites Cortés to explain his god. When offered a psychedelic cactus to speak in the sacred tongue, Cortés accepts.

A hallucinogenic sequence ensues, portraying a mythical journey through time—spanning colonial violence, Mexico’s eventual transformation, and the paradoxical consequences of conquest. In this alternate vision, Cortés is executed, and the Mexica reclaim narrative control.

The novel closes with images of preparation—not for peace, but for confrontation. Moctezuma’s return to the citadel, the city bracing itself, and the eagle warriors readying for defense all evoke the prelude to rupture.

Yet the climax is not a battle, but a spectral vision of what might have been: a moment suspended in history, where an empire teeters between collapse and resistance, its fate already sealed by internal fragmentation as much as external invasion.

Through its mosaic of voices, shifting allegiances, and dreamlike episodes, You Dreamed of Empires reconstructs a pivotal historical encounter not as a clash of civilizations, but as an implosion of meaning, authority, and identity on both sides. It is a story of doomed glory, blurred truths, and the fatal seduction of empire.

Characters

Jazmín Caldera

Jazmín Caldera serves as the primary lens through which much of the reader’s encounter with Tenochtitlan is filtered. A captain from Extremadura, Caldera is not merely a witness to conquest but a reluctant and introspective participant.

He is deeply perceptive, frequently caught between the martial expectations of his Spanish comrades and the overwhelming spiritual and cultural dissonance of the Mexica world. His initial reaction to the opulent banquet, repulsed by the scent of death and ritual clinging to the Aztec priests, encapsulates his psychological disorientation.

Yet, his instinctive caution and sincerity also make him stand apart from the bolder, more arrogant Cortés. Caldera’s honest responses to Princess Atotoxtli and his later existential reflections within the palace walls reveal a man acutely aware of the fragility of their imperial gamble.

As he becomes physically lost within the palace, Caldera’s journey morphs into a symbolic pilgrimage—his confusion a mirror of Spain’s overreach. Ultimately, he emerges not as a conqueror but a contemplative observer, increasingly skeptical of the mission and overwhelmed by the grandeur and danger of the empire he has penetrated.

Moctezuma

Moctezuma is a tragic and spectral figure throughout You Dreamed of Empires, portrayed as both a supreme ruler and a crumbling monument. Consumed by visions and shamanistic rituals, he is less a political actor than a mystical vessel tormented by omens and metaphysical dread.

His addiction to hallucinogens isolates him further from reality, and his descent into near-madness parallels the decay of the empire itself. Despite his position as emperor, Moctezuma increasingly becomes an impotent figure—unable to command loyalty, interpret the times, or decisively act.

He punishes dissent harshly but randomly, such as in the cruel execution of his niece, and his obsession with horses reveals a man fixated on portents rather than power. His final encounter with Cortés, couched in theological dream-logic, suggests that his imperial authority has become symbolic and performative rather than functional.

Moctezuma embodies the empire’s mystical grandeur and its paralyzing inertia in the face of imminent collapse.

Atotoxtli

Atotoxtli is the sharpest political mind in the Mexica court. As Moctezuma’s sister, wife, and co-ruler, she navigates the labyrinth of dynastic and imperial politics with clarity, frustration, and strategic acumen.

Her early confrontation with Cortés and Caldera signals her capacity to read between diplomatic lines and challenge the Spaniards’ narrative. Unlike her brother, she is grounded in the practical needs of empire—military strength, alliances, and sovereignty.

Her private fury over being displaced from her chambers is less personal grievance than symbolic warning: she senses the corrosion of the empire’s ceremonial core. Atotoxtli’s engagements with Tlilpotonqui and Cuauhtemoc show her as a builder of plans, including using proxy wars and strategic marriages to shore up weakening alliances.

Her guarded yet empathetic conversation with Malinalli also reveals her capacity for both political manipulation and female solidarity. Ultimately, Atotoxtli represents what Moctezuma cannot be—a leader willing to act before it is too late.

Tlilpotonqui

Tlilpotonqui is the empire’s bureaucratic backbone—its cihuacoatl and institutional memory. Once a trusted adviser to Moctezuma, Tlilpotonqui finds himself increasingly sidelined as the emperor drifts into abstraction and other figures like Atotoxtli and Cuauhtemoc assert themselves.

He is a man of rules, recitations, and rituals, yet the order he represents is eroding. Tlilpotonqui’s confusion in the face of dream-logic, his inability to decipher new metaphors, and his increasingly frantic attempts to maintain protocol all underline his decline.

When he suppresses dissent among the calpulli leaders with brute force, it is not an act of strength but desperation. His realization that he has been removed from the inner circle—and possibly marked for death—is both pathetic and profound.

Tlilpotonqui symbolizes the administrative machinery of empire, sputtering and ineffective in the face of existential threats.

Hernán Cortés

Cortés is rendered in You Dreamed of Empires as both audacious and dangerously myopic. His religious zeal and imperial ambition drive him to overreach again and again, most strikingly in his ill-fated attempt to Christianize the Templo Mayor without permission.

Despite occasional attempts at diplomacy, his arrogance is a fatal flaw, and he consistently misreads the spiritual and political weight of Mexica rituals. His abuse of Malinalli, his strategic boasts at diplomatic meals, and his disdain for local customs reveal a man who understands domination but not diplomacy.

When he finally consumes the hallucinogenic “cactus-of-tongues” and descends into a prophetic dream, he confronts—ironically—his own historical footprint. His execution at the story’s end is less a death than a narrative reversal, imagining a world where the invader is swallowed by the civilization he aimed to conquer.

Malinalli (La Malinche)

Malinalli is the novel’s most enigmatic and ambivalent figure. Caught between servitude and influence, she functions as a crucial translator—linguistically, culturally, and emotionally.

She suffers violence at the hands of Cortés yet remains indispensable to his campaign, and her quiet intelligence constantly negotiates survival with subversion. Her conversation with Atotoxtli is a brilliant display of veiled language and subtle maneuvering.

Though outwardly compliant, Malinalli carefully withholds loyalty, choosing instead to adapt and endure. Her power lies in her voice, which mediates between civilizations.

Yet she is also vulnerable, perpetually at the mercy of male authority—until she carves a fragile space for herself within the imperial court. She represents the fraught nature of cultural brokerage: a figure neither wholly betrayed nor betrayer, neither victim nor agent, but something hauntingly in-between.

Badillo

Badillo, Cortés’s stuttering servant and horse handler, is both comic relief and symbolic figure. His physical separation from the main Spanish party—tending to the horses alone—mirrors the isolation and confusion experienced by the entire expedition.

His accidental discovery of the orchard and his dreamy interactions with the palace architecture reveal a man out of place, unaware of the deeper currents around him. Yet, in his simplicity and loyalty, Badillo also serves as a measure of the Spaniards’ ignorance.

His peaceful tending of horses amidst the looming doom encapsulates the surreal lull before catastrophe—a naïve echo of the conquistadors’ broader misjudgment.

Cuauhtemoc

Cuauhtemoc is the last great military hope of the Mexica, though he operates mostly in the background. While Atotoxtli maneuvers diplomatically and Tlilpotonqui clings to ceremonial order, Cuauhtemoc represents the warrior’s ethos.

He is not reckless but prepared, forging plans with Atotoxtli to provoke and use proxy war as a means to reclaim agency. In contrast to Moctezuma’s paralysis, Cuauhtemoc is action-oriented, clear-eyed, and grounded in the realities of power.

His limited but sharp appearances mark him as the coming generation of Mexica resistance—pragmatic, loyal, and brutal when necessary. He is the figure poised to inherit a collapsing empire and perhaps resurrect it through force.

Each of these characters contributes to the richly layered tapestry of You Dreamed of Empires, their intersecting fates dramatizing not only the downfall of a civilization but the human contradictions embedded in conquest, collaboration, and collapse.

Themes

Cultural Alienation and Misrecognition

The encounter between the Spaniards and the Mexica elites is shaped less by outright hostility and more by an underlying alienation so profound that it borders on tragic farce. In You Dreamed of Empires, much of the unease stems not from military aggression but from mutual incomprehension.

This is expressed through misread social cues, ritual performances misunderstood by foreigners, and linguistic translation that becomes a filter rather than a bridge. For instance, the diplomatic table scene where insults are softened or fabricated praise is invented by translators underscores a political environment entirely built on performance, dissimulation, and illusion.

The Spaniards misinterpret the Aztecs’ symbolic, theatrical politics as weakness or absurdity, while the Mexica see the invaders’ bluntness and irreverence as a dangerous form of madness. The obsession with horses—creatures unknown to the Mexica—embodies this estrangement, as Moctezuma projects mythic and divine qualities onto them, misunderstanding their role in Spanish warfare while symbolically trying to absorb their power into the empire’s own mythos.

Meanwhile, the Spaniards view Mexica customs through a Christian moral lens, recoiling in horror from practices like human sacrifice yet unable to recognize their own role as aggressors. This reciprocal alienation fuels a failure to negotiate or even co-exist on equal terms, creating a situation where misunderstanding leads to escalation.

The physical disorientation of the Spaniards lost in the palace mirrors their cultural and psychological dislocation, and the Mexica’s attempts to manage the foreigners through hospitality, pageantry, and myth ultimately collapse under the weight of unbridgeable worldviews.

Imperial Decay and Stasis

Throughout the narrative, the Mexica Empire is presented as an institution so vast and overburdened by tradition, superstition, and ceremonial inertia that it becomes incapable of meaningful action. Moctezuma’s prolonged nap—both literal and metaphoric—functions as a haunting metaphor for imperial paralysis.

While Atotoxtli, Tlilpotonqui, and Cuauhtemoc strategize around him, the emperor indulges in ritualized food, hallucinogens, and cryptic speech, embodying a sovereignty that has lost its grip on reality. The palace, labyrinthine and mysteriously maintained by unseen servants, becomes a hollow monument to an empire that is simultaneously luxurious and dysfunctional.

The administrative elite are preoccupied with recitations, symbols, and coded language, while the political ground beneath them shifts violently. Tlilpotonqui, once a confident adviser, increasingly finds himself confused and irrelevant, his bureaucratic recitations failing to connect to immediate political needs.

Ritual replaces governance, metaphysics displace strategy, and mythic interpretation obscures clear decision-making. This decay is not merely symbolic—it has real consequences, as loyal states drift away, allies like the Tlaxcalteca become threats, and internal factions begin to act independently.

The empire, once terrifyingly powerful, now staggers under its own traditions, its grandeur making it brittle rather than resilient. Even its most intimate rituals—Moctezuma’s solitary feasts, the silent audience chamber—feel embalmed rather than alive.

This immobility is contrasted sharply with the Spaniards’ disorganized but goal-oriented movement. The Mexica, though still formidable, are depicted as frozen in time, ruled by an emperor more concerned with prophecies than policy, leaving the future to be written not by him, but by those willing to act.

Gender, Power, and Political Perception

Atotoxtli, Moctezuma’s sister and consort, emerges as a powerful embodiment of the role gender plays in the exercise and perception of power within the novel. In a patriarchal society defined by ritual hierarchy, her political acuity is simultaneously indispensable and suppressed.

She is one of the few characters who recognizes the empire’s vulnerabilities—not as metaphysical misalignments or divine portents but as real-world threats: fracturing alliances, weakened warriors, and foreign adversaries immune to traditional frameworks of power. Her interactions with both Tlilpotonqui and Malinalli display her ability to command, negotiate, and manipulate, though always within the confines of what is deemed appropriate for her gender.

Her confrontation with Moctezuma over having to host the Spaniards in her chambers exposes the humiliation layered into gendered spaces of authority. Her efforts to engage Malinalli in political alliance through a shared sense of female agency—though subtle—reveal a sharp mind trying to create new paths of influence outside the crumbling court structure.

Meanwhile, Malinalli herself is a study in duality: linguistically essential, yet exploited and dismissed, her body and voice are used by the Spanish invaders as tools of conquest. Her ambiguity—neither fully traitor nor fully loyalist—reflects how women are uniquely burdened with the role of mediation in imperial conflict.

Even her moments of choice are bound by the brutal limits imposed by male commanders like Cortés. The novel suggests that within both Mexica and Spanish structures, female power operates largely in the shadows, yet it remains one of the few loci of clarity and realism amidst the hallucinations and rituals of crumbling empires.

Identity and Assimilation

The characters in You Dreamed of Empires often find themselves suspended between cultural identities, caught in moments where their allegiance, heritage, and survival instincts are at odds. Jazmín Caldera becomes the emblematic figure for this theme, not through overt betrayal or loyalty, but in his quiet, confused awe at Tenochtitlan.

Though a Spanish captain, his perception of the city is not filtered through religious contempt or colonial ambition. Instead, he finds beauty in its order, sophistication in its rituals, and even philosophical merit in its tzompantli.

He is not seduced by Mexica culture in the traditional sense; rather, his identity becomes fragmented as he observes, follows, and ultimately drifts away from the conquest’s brutal agenda. The surreal nature of the palace—with its chocolate-scented corridors and ghostly servants—functions as a space of cultural unmooring.

Aguilar, the tattooed former friar, straddles even more explicitly the divide between the Christian world and indigenous reality, coaching Caldera in donning native clothing, a symbolic and literal act of transmutation. Malinalli, too, embodies a hybrid identity—Christian convert, Nahua noble, concubine, translator—serving both conqueror and court with no clear allegiance.

These figures are not merely caught between two sides; they live in a liminal zone where categories dissolve. The conquest is not only about land or power but about what survives of a person once they’ve been translated into someone else’s myth, language, or prophecy.

The novel critiques both the purity of imperial identity and the moral simplicity of betrayal, insisting instead on the psychological complexity of those who survive by becoming other.

Prophecy, Hallucination, and the Illusion of Destiny

Moctezuma’s psychological arc is saturated with visions, hallucinogens, and the compulsive search for divine confirmation of imperial destiny. Unlike his courtiers, who seek strategic clarity, Moctezuma seeks metaphysical meaning.

His obsession with prophecy and ritual clouds his judgment, encouraging inaction cloaked in sacred inevitability. Rather than prepare for war or negotiate alliances, he consumes mushrooms and interprets dreams, convinced that history is not to be shaped but revealed.

The novel critiques this fatalism through both satire and tragedy. His detachment turns him into a passive figurehead, surrounded by handlers who must interpret his mutterings while the empire collapses.

The psychedelic encounter between Moctezuma and Cortés, in which they share a drug-induced dialogue about gods, war, and destiny, becomes a hallucinatory parody of diplomacy. Yet within this surrealism lies an acute commentary on how both sides—Mexica and Spaniard—are entranced by narratives of chosen people, divine missions, and historical inevitability.

The line between sacred vision and political madness dissolves, especially when Moctezuma sentences his niece to death without remorse, guided not by law or governance but by a warped sense of divine order. The climax, where Cortés is offered a drug to speak the “Xleek” tongue and undergoes a vision of New Spain, cements the theme: conquest and religion are inseparable, not only in rhetoric but in the hallucinatory logic of those who believe they are instruments of fate.

The tragedy lies not in failed politics, but in the surrender of human agency to visions that promise clarity and instead deliver annihilation.