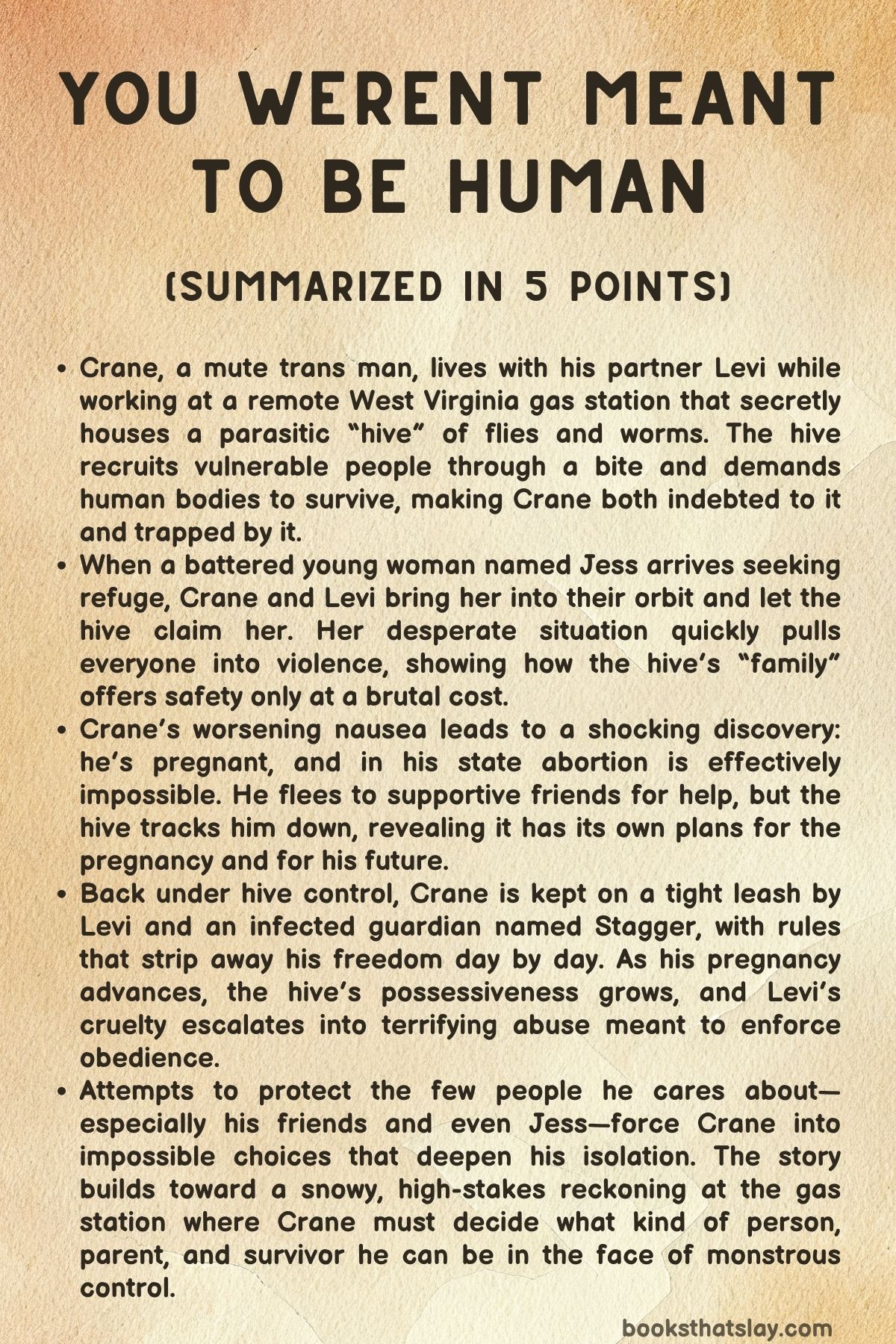

You Weren’t Meant To Be Human Summary, Characters and Themes

You Weren’t Meant To Be Human by Andrew Joseph White is a claustrophobic body-horror novel about survival, coercion, and the price of belonging. Set around a lonely gas station in rural West Virginia, it follows Crane, a mute trans man who has been “saved” by a parasitic hive of worms and flies that offers desperate people a place to go—if they feed it.

Crane’s fragile stability collapses when he discovers he is pregnant, and the hive decides the baby is theirs. What follows is a brutal fight for bodily autonomy and identity inside a community that calls itself family while acting like a cage.

Summary

Crane works nights at an isolated gas station in the mountains of West Virginia. He and his partner Levi, an older ex-soldier, keep the place running and keep a secret locked behind a back-room door.

Inside that room lives the “hive,” a mass of flesh flies and worms that once found Crane when he was suicidal and offered him a path to live. The hive recruits the desperate, marks them with a bite, and demands to be fed human bodies.

Crane believes he owes his life to it and that leaving would mean death.

One evening, a barefoot figure appears on the security monitor, and the hive stirs like it senses a newcomer. Crane goes outside first and finds a young woman limping and bleeding, filthy from the road.

She introduces herself as Jess. Crane gives her water, food, and first aid, and locks up the station.

Jess hints that she has fled abuse from her boyfriend Sean, who lives near a nearby lumberyard. She asks to see the hive to thank it.

Levi unlocks the back room, and Jess is bitten, becoming a recruit. She spends the next week recovering with their manager, Tammy, while Levi leaves to help another hive outpost.

Crane, meanwhile, has been queasy for weeks but assumes it’s stress.

Late on July 4th, Jess sends frantic messages: she fought with Sean, hit him too hard, and thinks he might still be alive. Tammy orders Crane to go deal with it.

At Sean’s house, Crane finds Sean on the floor with a crushed skull and faint signs of life. Hive rules allow no loose ends; anyone who knows too much must either join or die.

Crane tries to push Jess to finish the killing as part of her initiation, but she breaks down and refuses. Crane kills Sean himself with a hammer.

They haul the body back, and Tammy makes them feed it to the hive. As the worms and flies strip the corpse, Crane vomits outside.

Tammy, noticing Crane’s constant nausea, forces him to take a pregnancy test. Crane insists this can’t be possible while on testosterone, but the test comes back positive.

He goes cold. In West Virginia, abortion is treated as murder, and he knows the hive won’t tolerate him leaving.

Terrified he might hurt himself, Crane drives three hours to friends Aspen and Birdie, who live near Washington, DC, with their three-year-old daughter Luna. Using his AAC tablet, he tells them he’s pregnant and scared.

They’re alarmed but steady, and Aspen quickly arranges an out-of-state abortion appointment for the next morning. Crane spends a gentle holiday afternoon with their family, clinging to normalcy he hasn’t felt in years.

He falls asleep in their bed, trying to believe he can make it to the clinic at dawn.

In the middle of the night he wakes sick again, then hears their back door splinter. A hooded intruder stands in the kitchen.

A hive bite marks his wrist, and when he speaks his voice carries the swarm’s whisper. He tells Crane to come home.

Crane remembers what happens to defectors: Levi once drowned a runaway recruit in their bathtub while Crane helped. The intruder is there for him.

To protect Aspen, Birdie, and Luna, Crane goes quietly. Outside, the man pins him in the car, lifts Crane’s shirt, and presses his face to Crane’s belly.

Crane realizes the hive already knows about the pregnancy and wants it.

They return to the gas-station base. Levi is waiting with a shotgun and fury.

Crane lashes out, striking Levi with a pipe, but Levi overpowers him. Levi confiscates Crane’s keys, removes anything he might use to hurt himself, and assigns the infected man—nicknamed Stagger—to watch him constantly.

Levi claims the hive wants the baby and that Crane will carry it. Crane begs to end the pregnancy, but Levi drags him home under guard.

The hive summons Crane to the back room. On his knees, shaking, he pleads for release.

The swarm speaks inside his head, calling him its child and saying this pregnancy answers an old wish: to be remade and guided by them. The fetus belongs to the hive because it needs a living carrier to bring new life into the sunlight it can’t reach.

Tammy examines Crane and estimates he is already eleven or twelve weeks along. The clinic plan would have failed anyway.

Crane is trapped.

Weeks grind forward under new rules: no driving, no leaving without Levi’s permission, and no tools or sharp objects unless supervised. Stagger sleeps nearby like a watchdog but treats Crane with soft, wordless care, signing apologies when the hive hurts him.

Jess and Irene, another recruit, rotate in and out. Levi grows more controlling, and the hive’s hunger never stops.

Crane works extra shifts at first to exhaust himself, then Levi pulls him off the schedule entirely. Cut off from his phone, Crane can’t contact Aspen or Birdie, and he spirals between rage and numbness as his body changes against his will.

When the baby moves for the first time, Crane cracks. He storms into the hive room and grabs at a worm, trying to crush it and force the swarm to stop this.

The hive shrieks through him. Stagger restrains him, and Crane collapses sobbing into Stagger’s arms.

Levi responds by tightening the leash: another infraction, he says, will mean broken bones. Crane doesn’t know why Levi needs this child so badly, only that everything is sliding toward violence.

The violence arrives anyway. Jess shows up one night drunk and bleeding.

She confesses she’s pregnant with Levi’s child and tried to end it herself. She’s hemorrhaging and near collapse.

Crane and Stagger rush to help, but Levi intercepts them, refuses to take Jess to a hospital, and sends Irene to Tammy instead. Levi reveals he has cracked Crane’s phone and read his old messages.

He used the phone to lure Aspen and Birdie to an abandoned livestock exchange. Then he smashes the phone and calls this Crane’s second strike.

At the auction building, Levi hands Crane their spare house key and orders him to make them leave West Virginia forever or Levi will kill them. Aspen and Birdie arrive terrified and stunned by Crane’s pregnancy.

They try to take him home with them. Crane insists, silently but firmly, that they leave without him.

When they refuse, he forces their hand by punching Aspen. Birdie drags Aspen away, furious and heartbroken, and promises never to come back.

As soon as they’re gone, Levi praises Crane’s obedience, rapes him on the concrete floor, then breaks two of his fingers as punishment. Crane returns home splinted, hollowed out, and telling himself he only has to survive until birth.

Desperation pushes him toward self-harm anyway; in one moment he leans into boiling water, trying to erase himself and the pregnancy, and whites out from pain.

Winter comes with a blizzard the night Crane goes into labor. They return to the gas station because the hive wants the birth close.

Tammy acts as midwife. Jess and Stagger make a nest of blankets by the hive door while Levi paces with a shotgun.

During a break, Crane smokes outside with Jess and Stagger. Jess talks about California, about leaving, about maybe hiding the baby somewhere the hive can’t reach.

Crane decides Jess is the only one who might escape. He steals Levi’s truck keys from his go-bag and presses them into Jess’s hand, ordering her to drive west immediately.

She hesitates, terrified, but he doesn’t give her a choice.

A car pulls up while Jess is still outside. A middle-aged couple approaches, asking for help.

Crane recognizes his parents. They don’t recognize him at first; they still see their missing daughter Sophie, not the man in front of them.

When his father studies his face and swollen belly, the truth lands. His parents want to take him to a hospital, to bring him home.

Jess lies quickly, saying danger is near, and sends them down the road to wait with a phone number scribbled on a napkin. They hug Crane goodbye through tears.

Jess kisses him and drives off into the storm in Levi’s truck.

Labor accelerates. Crane, shaking and vomiting, pushes on hands and knees while Tammy coaches him and Stagger braces his back.

A tiny girl is born. Crane holds her, expecting the hive’s infestation, but she seems normal—just a small, wet, crying baby.

Tammy cuts the cord and hands the placenta to Levi, who wraps it to feed the hive. Levi moves to “introduce” the baby to the swarm.

The worms and flies awaken, claiming her as “our little one. ” Levi shows a moving scar in his own flesh, proving he carries a worm inside, and insists the child needs the hive the way they all did.

Crane sees what that means: a life hunted, bitten, owned. There is no safe future for his daughter if the hive takes her.

With no exit left, he makes a final, terrible choice to spare her. He bites into her throat and kills her in his arms.

Tammy screams. Levi lunges for the body.

Stagger tackles Levi to protect Crane. Levi fires the shotgun wildly, fatally shooting Tammy and blowing Stagger’s head apart.

Stagger dies at Crane’s feet.

Crane stands, wrecked but clear. He tries the shotgun, but it jams.

He grabs the hammer from his bag and smashes Levi’s skull until Levi goes still. Then he pries open Levi’s living scar, pulls out the single worm inside him, and crushes it.

The hive falls silent, cut off from its strongest host.

In the aftermath, Crane dresses in clean clothes, wraps his daughter’s body in his parents’ blanket, takes Levi’s jacket, and walks into the snow with Levi’s phone. He calls his parents on video.

His father answers, grieving but present, and recognizes him. Crane finally lets himself be seen—not as the hive’s child, not as Levi’s captive, but as Crane, alive and walking toward whatever comes next.

Characters

Crane

Crane is the emotional and moral core of You Werent Meant To Be Human, a mute trans man whose life has been shaped by survival, coercion, and a desperate need for belonging. The hive “saved” him when he was suicidal, and that origin story becomes a psychological leash: he experiences gratitude and horror in the same breath, which keeps him trapped even when the hive’s rules are monstrous.

His muteness and reliance on an AAC tablet sharpen his isolation—he is constantly translating panic and pain into a medium others can ignore, reinterpret, or weaponize. Crane’s pregnancy is the novel’s crucible: it forces every fault line in his identity to split open at once—his relationship to his body, his transition, his autonomy, and his right to live without being claimed by something else.

Throughout the story he tries to stay humane inside an inhuman system, and that struggle manifests as a tense mix of tenderness and violence. He cares for Jess, protects Aspen and Birdie, and loves the idea of safety so fiercely that he will mutilate himself or destroy what he loves to prevent its capture.

His final choice—killing his newborn daughter to spare her the hive—lands not as cruelty but as the most tragic version of agency he can still reach, a decision born from terror, love, and learned hopelessness. Crane ends the book shattered yet finally self-directed, severing the hive and Levi not just physically but spiritually, stepping into a world that can no longer define him as prey.

Levi

Levi is both intimate partner and primary jailer, a former soldier whose devotion to the hive has calcified into ideology and cruelty. He presents himself as protector—locking away weapons, controlling Crane’s movements, assigning watchers—but the “protection” is indistinguishable from captivity, and his military mindset frames domination as necessary order.

Levi’s bond with Crane is laced with possessiveness: he sees Crane’s body, labor, and future as hive property, and he enforces that belief through escalating violence, threats, and rape. Even when he seems calm, Levi is a man who has outsourced his conscience to a rulebook; he kills defectors without hesitation and expects gratitude for his discipline.

His love is real in the way obsession can be real, but it is love that cannot tolerate autonomy. The pregnancy makes Levi’s contradictions louder—he wants Crane alive and compliant, yet he repeatedly brutalizes him; he wants the baby for the hive, yet cannot imagine the child outside that ownership.

In the end Levi’s authority collapses under the weight of what he has built. His death is the last necessary rupture, and the worm inside him literalizes what he has become: a human host for something that feeds on control, loyalty, and fear.

Tammy

Tammy functions as the hive’s administrator and pragmatic caretaker, a figure whose competence makes her both safer and more dangerous than Levi. She runs the gas station, manages recruits, and understands the hive’s needs with clinical clarity.

Unlike Levi, Tammy is not governed by rage; she is governed by the logic of continuation. That logic allows her moments of genuine care—checking Crane’s health, splinting his fingers, midwifing his labor—while simultaneously making her complicit in atrocities, including feeding bodies to the hive and enforcing Crane’s forced pregnancy.

Tammy’s moral profile is unsettling because it is so human: she is capable of empathy but has decided that the hive’s survival, and the community it creates, outweigh individual freedom. Her alarm at Crane’s pregnancy initially reads as concern, yet she quickly becomes the machine that monitors it, measuring weeks and fetal growth as though her attention could domesticate the horror.

During the climax her instinct is still preservation—trying to keep Jess’s escape quiet, trying to complete the birth, trying to “introduce” the baby to the hive. Her death at Levi’s hands underscores the story’s indictment of systems that consume even their best managers; loyalty does not protect her from the violence she helped normalize.

Jess

Jess begins as the archetypal recruit: desperate, abused, and looking for something to make her feel chosen rather than trapped. Her initial vulnerability—filthy, limping, hungry—mirrors Crane’s own origin with the hive, which is why he responds to her with such protective urgency.

As she recovers, Jess becomes a living test of the hive’s promise: she wants to believe the bite means rescue, community, transformation. But her initiation is soaked in blood when she kills Sean, and that trauma reverberates through her arc.

Jess is volatile because she is torn between gratitude and disgust; she lashes out at Crane, projects onto him, and tries to force herself into the role the hive expects, even attempting to abort Levi’s child alone. Yet she is also the character most capable of imagining a future beyond the hive.

Her talk of California is not idle fantasy but a conceptual escape hatch, and by the end she is the only one Crane believes can run far enough to live. Jess’s escape in Levi’s truck is the novel’s sliver of outward hope.

She carries damage, guilt, and a hive bite she didn’t fully consent to, but she also carries the possibility that survival can mean more than obedience.

Stagger

Stagger is one of the most haunting embodiments of the hive’s ambiguity—an infected man whose body is already claimed, yet whose presence is consistently gentle. He is physically imposing, nearly wordless in speech but communicative through signing, and he becomes Crane’s closest thing to safety inside captivity.

What makes Stagger important is that his kindness isn’t performative; he restrains Crane when necessary, apologizes when he hurts him, and offers quiet companionship without demanding anything in return. Stagger represents the hive’s seductive lie: that infection can coexist with care, that being remade doesn’t erase tenderness.

At the same time, his role as enforcer under the hive’s rules shows how even good people can be turned into tools of control. His death is brutal and symbolic—shot twice, skull destroyed—because it annihilates the last soft buffer between Crane and Levi.

The loss of Stagger is the moment the system stops pretending it has room for gentleness, and it leaves Crane fully alone to decide his final actions.

Aspen

Aspen is a lifeline to Crane’s past and to a world not organized around the hive. They are practical, connected, and protective, immediately mobilizing resources for an out-of-state abortion without making Crane justify his fear.

Aspen’s strength is relational rather than physical; they believe in networks, in calling people, in creating options. That belief becomes a threat to the hive because it reintroduces choice.

When Levi forces Crane to drive Aspen and Birdie away, Aspen’s devastation is palpable not only because they lose Crane, but because they see how completely he has been cornered. Their willingness to leave when Crane insists is both heartbreaking and loving—they understand that refusing might get them killed.

Aspen stands for the possibility of care without ownership, and their absence afterward amplifies the cruelty of Crane’s isolation.

Birdie

Birdie is warmth, domestic steadiness, and emotional truthfulness in You Werent Meant To Be Human, offering Crane a space where he is not a weapon or a vessel but a person. Their home scenes—pasta, movies, naps, bedtime rituals—aren’t filler; they are a glimpse of the life Crane wanted before the hive reclaimed him.

Birdie’s empathy is grounded in shared vulnerability, especially around misconceptions about testosterone and pregnancy, which keeps their support from feeling abstract. Their anger when Crane punches Aspen is fierce and believable, because from Birdie’s view it looks like betrayal.

But that anger is also proof of love: they care enough to feel wounded rather than numb. Birdie represents family chosen by tenderness instead of fear, and the way Crane sacrifices that bond to protect them makes their character echo long after they leave.

Luna

Luna, though small and young, carries enormous thematic weight. She is innocence without conditions, interacting with Crane as a trusted adult rather than a “case” or a body under surveillance.

Her constant needs—snacks, naps, cuddles—draw Crane into everyday life, anchoring him briefly in normalcy. Luna’s presence also raises the stakes of the hive’s reach; when the bite-marked intruder appears in her house, the violation feels catastrophic because it threatens not just Crane but a child who has no idea such monsters exist.

Luna functions as a mirror for what Crane is trying to protect in himself: softness, play, the right to exist without being harvested.

Irene

Irene arrives late but sharpens the story’s portrait of recruitment and complicity. As a recently recruited ex-con, she is blunt, hardened, and eager to find her place in the hive’s hierarchy.

She speaks of prison and survival with a casualness that suggests she has learned to normalize brutality, making her an easy fit for the hive’s moral ecosystem. Irene’s cracking of Crane’s phone is a small act that has massive consequences, showing how power in the hive isn’t only about physical force but about surveillance and information.

She embodies a different flavor of loyalty than Levi’s: not romantic obsession, but pragmatic allegiance to the system that fed her when nothing else would. Irene is dangerous because she is still proving herself, and people proving themselves often escalate harm.

Sean

Sean exists primarily through the aftermath of violence, but his character matters because he reveals the stakes of Jess’s past. He is presented as abusive and controlling, a man whose relationship with Jess drove her into the forest and toward the hive.

His death is the first place Crane is forced to act as executioner not for survival but for policy, and that shift corrodes him. Sean’s barely-alive body on the floor is also a grim introduction to what initiation costs: Jess must either kill him to belong or refuse and be judged weak, and Crane must perform the cruelty she cannot.

Sean symbolizes the old world’s violence that pushes people into new violence, closing the loop of harm.

Themes

Bodily autonomy under coercion

Crane’s pregnancy becomes a battleground over who gets to decide what his body is for, and the story pushes that conflict into every corner of his life. The hive’s claim on the fetus is not presented as a metaphysical idea but as a blunt seizure of agency: rules clamp down on his movement, his work, his tools, even his phone, until his own body feels like a site owned by others.

That takeover lands in a specific political reality, where abortion access is criminalized, making his fear not theoretical but immediate and practical. The legal threat and the hive’s threat create a double cage: one enforced by the state, one enforced by a parasitic community that calls itself salvation.

Crane’s attempts to reclaim control show how autonomy is not a single choice but a daily struggle. He keeps taking testosterone in secret, tries to provoke the hive into ending the pregnancy, and later considers burning himself to stop it.

None of these are framed as simple self-destruction; they are desperate bids to regain authorship over his life in the only ways left to him. The bodily policing he faces is also gendered and social.

The woman at Dollar General reads his pregnant body as proof that motherhood should “correct” him, treating his transition as a mistake to be undone by biology. That moment matters because it mirrors the hive’s logic: both assume pregnancy defines identity and destiny.

In You Werent Meant To Be Human, the horror is not just that Crane is forced to carry a child, but that everyone around him feels entitled to narrate what that child means, while he is barely permitted to speak. His final act—killing his newborn daughter to spare her from infestation—lands as the most extreme, tragic expression of autonomy available to him.

It is a choice made inside a world that has eliminated all humane options. The theme insists that autonomy without real freedom becomes a cruel parody, and that coercion can dress itself as care, religion, family, or “community” while still stripping a person down to property.

Survival, complicity, and moral injury

Crane’s relationship with the hive is rooted in rescue: it found him when he was suicidal, offered belonging, and supported his transition. That origin makes his later captivity morally tangled rather than cleanly villain-versus-victim.

He knows what the hive does, has lived by its rules, and has participated in its violence, including helping Levi kill defectors. When he kills Sean to protect Jess and uphold hive policy, the scene shows how survival inside a violent system often requires becoming one of its instruments.

This is moral injury in slow motion: Crane is not ignorant of harm, and that knowledge corrodes him precisely because he once believed the hive was his way out of despair. The story keeps returning to the difference between being saved and being owned.

The hive frames itself as a refuge for desperate people, but its refuge is conditional on loyalty, secrecy, and feeding it bodies. That structure turns gratitude into a leash.

Crane clings to the hive because leaving would mean death, and because psychologically he cannot easily sever the bond with what kept him alive. His nausea, numbness, and spiraling self-harm thoughts read as the cost of holding incompatible truths: he needs to live, yet the terms of living demand cruelty.

Levi embodies the sharpest edge of this theme. He is both partner and enforcer, someone Crane loved and relied on, and the person who rapes him, breaks his fingers, and threatens his friends.

The intimacy makes the violence harder to compartmentalize. Crane’s survival strategy becomes performance—obeying, faking hatred toward Aspen and Birdie, enduring daily humiliations—until endurance itself feels like betrayal of his own values.

Even smaller moments, like keeping silent when Jess escapes, show survival as a chain of compromises where the “right” action risks someone else’s life. By the end, the moral equation collapses into raw necessity.

Crane kills Levi and the worm inside him not out of triumphant justice but because there is no remaining path that doesn’t end in total annihilation. The theme isn’t that survival always demands complicity; it’s that coercive worlds are designed so that resisting harm and staying alive can become mutually exclusive.

You Werent Meant To Be Human portrays the aftermath of that trap as grief, dissociation, and the haunting sense that even freedom arrives soaked in what you had to do to reach it.

Identity, embodiment, and the violence of being readable

Crane’s transness is not treated as a side note or metaphor; it is the lens through which every threat in the book becomes sharper. His body is repeatedly interpreted by others in ways that deny him self-definition.

The hive validates his transition at first, allowing him to become Crane, yet later reduces him to a vessel for its reproduction. The broader social world echoes that reduction: the casual assumptions at the gas station, the woman’s prayer-talk about motherhood, and the state’s abortion laws all position his body as an object others can classify and regulate.

Pregnancy intensifies this violence because it makes him highly “readable” to strangers who don’t know his history and don’t think they need to. His masculinity is treated as fragile, provisional, and correctable by biology, which turns his pregnant belly into a public argument about who he is allowed to be.

The story shows that embodiment for Crane is already complicated by dysphoria and by the labor of maintaining testosterone in a hostile environment. When pregnancy erupts into that reality, it feels like a betrayal not just of expectation but of the fragile trust he has built with his own body.

His panic when he first feels the baby move is not about impending parenthood in the abstract; it is about being forced into a physical narrative he never consented to. The moment his parents appear at the gas station underlines this theme from another angle.

They see his pregnant body and have to reconcile their missing daughter with the man in front of them. Their recognition is both tender and destabilizing; it offers a path back to family while also reminding him that his body carries histories he can’t fully erase.

In the hive, identity is similarly policed through bites, scars, and the whispering voice, binding people to a collective that claims to know them better than they know themselves. Crane’s muteness adds another layer: because he does not speak aloud, other people fill the silence with their own stories about him.

His AAC tablet is a tool for truth, but it cannot protect him from interpretation or force. In You Werent Meant To Be Human, the central horror of identity is the demand to be legible on other people’s terms.

Crane’s fight is not to discover who he is, but to survive a world that keeps insisting it already knows.

Abuse disguised as love and protection

The novel tracks how control can masquerade as devotion, making it hard for victims to name what’s happening to them. Levi repeatedly uses the language of safety to justify domination: taking away keys to prevent self-harm, assigning a constant escort, locking up weapons, monitoring shifts.

In isolation, some of these acts could look like care; together, they form a machinery of captivity. The cruelty is not just physical but narrative—Levi insists he is doing what the hive wants, that Crane will understand later, that the baby is “needed.

” By framing violence as duty and intimacy as entitlement, he blurs the line between partner and jailer. Crane is trapped not only by threat of death but by love’s leftover reflexes: the memory of Levi as the man who shared work, a bed, a life.

That residue makes resistance psychologically exhausting because resisting Levi also means mourning what he used to represent. The hive operates similarly.

It calls Crane “our child,” says his pregnancy fulfills his old plea to be remade, and positions its demands as a continuation of the care that once saved him. This is grooming at a community level: rescue becomes leverage, gratitude becomes obedience, belonging becomes a debt that can never be repaid.

Even Tammy’s role complicates the theme. She is midwife, supervisor, and enforcer, sometimes alarmed for Crane, sometimes complicit in keeping him in place.

Her divided position shows how abusive systems recruit ordinary people into making harm look normal. Jess’s arc demonstrates the same pattern from a different starting point.

She arrives fleeing a boyfriend who abused her, and almost immediately enters another structure that offers shelter only by consuming her autonomy. When she becomes pregnant and tries to abort in secret, her contempt toward Crane looks less like simple cruelty and more like a distorted mirror of her own terror about what pregnancy means in this world.

The theme insists that abuse thrives on confusion—on the idea that if someone claims love loudly enough, harm must be part of love. Crane’s final rupture with Levi, and his decision to kill the worm inside Levi’s body, is a refusal of that logic.

It is the moment he stops accepting protection as proof of affection. You Werent Meant To Be Human makes clear that the most dangerous abusers are often the ones who can point to real moments of care, because those moments become the cover under which everything else is permitted.

Chosen family, fragile refuge, and the cost of leaving

Against the hive’s counterfeit belonging, the scenes with Aspen, Birdie, and Luna show what care looks like when it is not transactional. Their home is warm in ordinary ways: pasta, naps, shared beds, a child demanding attention.

They respond to Crane’s pregnancy with fear and urgency, but that reaction comes from concern for his safety rather than ownership of his choices. Birdie’s insistence that he not face things alone, their immediate planning for access to abortion, and their willingness to shelter him all build a model of chosen family as a refuge built on consent.

The tragedy is that this refuge is fragile because the outside world is hostile and because the hive reaches across distance with lethal certainty. The intruder in their kitchen collapses the boundary between “safe place” and “unsafe world,” showing that for someone marked by the hive, safety is provisional.

Crane’s departure before dawn is heartbreaking not because he lacks love there, but because love cannot shield them from retaliation. He protects them by leaving, then protects them again by forcing them to leave Washville forever.

The livestock-exchange scene crystallizes the cost of leaving abusive systems: escape requires not only physical flight but social severing. Crane wounds Aspen and Birdie on purpose, turning their care into anger so they will survive.

That choice underscores how chosen family can be both salvation and vulnerability; people you love become targets. The theme also threads through Jess and Stagger.

Stagger’s gentleness toward Crane, his signed apology after restraining him, and his presence during labor show another kind of family emerging among the infected—one that defies the hive’s brutality. Jess’s escape, aided by Crane, is a final gift of possibility passed forward.

Yet every formation of family in the book carries a shadow of loss. Stagger dies defending Crane.

Tammy dies after trying to help him through labor. The baby dies by Crane’s own hand.

Family is portrayed as something you fight for, not something guaranteed to heal you. You Werent Meant To Be Human argues that refuge is real and necessary, but in a violent world it often comes with unbearable tradeoffs.

Leaving may save your loved ones, but it can also mean living with the fact that love wasn’t enough to keep everyone whole.