Do not go gentle into that good night Summary, Analysis and Themes

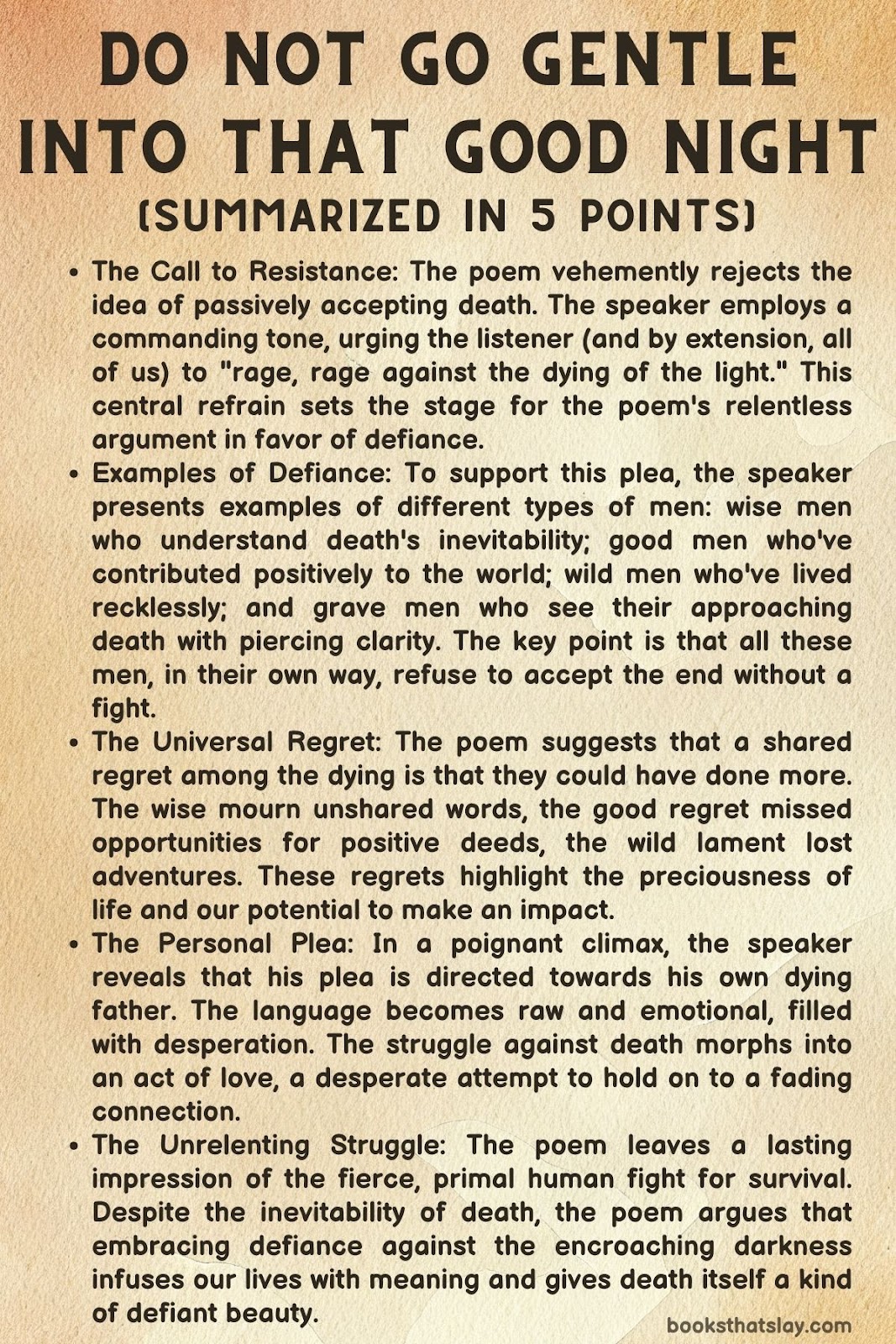

“Do not go gentle into that good night” is a poem by Dylan Thomas about resisting death fiercely. It’s a villanelle, meaning it has specific repeated lines.

The poem argues that the elderly should fight against the end instead of passively accepting it. Thomas uses examples of different types of men—wise, good, wild, and grave—to show that all, including his own dying father, should “rage against the dying of the light.”

Summary

In Dylan Thomas’s iconic villanelle, the speaker unleashes a powerful and urgent plea against surrendering to the inevitability of death.

The poem’s opening lines crackle with command, imploring the unspecified audience to resist the encroaching darkness and “rage, rage against the dying of the light.” This central metaphor, equating death with the quiet submission of night, sets the stage for the poem’s unflinching exploration of mortality.

The speaker’s argument against passive acceptance gains force as they present examples of men who, despite facing the end, refuse to acquiesce.

First come the “wise men,” who understand that death is a natural conclusion, a state of being that is “right.”

Yet, even with this knowledge, they do not give in. Their words, their very existence, becomes an act of defiance. Instead of fading quietly, they fought “against the dying of the light.”

The poem expands its focus to encompass “good men.” These are men whose deeds left a positive, lasting mark upon the world.

However, as their final moments draw near, they are just as filled with passionate resistance. The very acts of kindness and goodness they performed throughout their lives paradoxically fuel their fury against the fading light.

Even those who lived recklessly, the “wild men,” meet death with a similar defiance.

These men chased life’s pleasures and “caught and sang the sun in flight,” but now, aware of their limited time, lament the adventures they’ll never have. Their former recklessness transforms into a desperate yearning to grasp one more moment of life.

“Grave men,” those near death who see with blinding clarity the approach of their final moments, also resist.

Their vision, once perhaps clouded by everyday concerns, now becomes piercing. They see the potential they could have fulfilled, the dreams slipping from their grasp, and this knowledge ignites a last defiant stand.

In a heartbreaking revelation, the final stanza shifts to a deeply personal address. The speaker’s impassioned plea has been for his own dying father.

We witness a raw struggle – the speaker torn between the desperate hope for his father’s survival and the bleak awareness of inevitable loss.

He begs his father to fight, implores him to “curse, bless” him with the fire of life – anything but passive surrender.

Analysis

Structure and Form

- Villanelle: Thomas employs the intricate and demanding form of a villanelle. This form, with its repeated refrains and cyclical structure, reinforces the poem’s relentless insistence on defiance against death.

- Refrains: The two most famous lines, “Do not go gentle into that good night” and “Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” drive the poem’s emotional force. The repetition hammers home the central message of fighting against the inevitable.

- Tercets and Quatrain: The poem uses tercets (three-line stanzas) to present different types of men facing death, followed by a final quatrain (four-line stanza) where the speaker directly addresses his father.

Imagery and Symbolism

- Light and Darkness: The central contrast is between light, symbolizing life, vitality, and defiance, and darkness, representing death and the fading of existence. This battle plays out cosmically as well as personally.

- Natural Imagery: Thomas uses vivid natural imagery to heighten the emotional stakes. We see “frail deeds” dancing in a “green bay,” “the sun in flight,” and “blind eyes” blazing “like meteors.” These images connect individual lives to the grand cycles of nature.

- Paradox: The poem is filled with paradox, highlighting the contradictory forces at play. “Blind eyes could blaze” suggests seeing a different kind of truth in approaching death. Men who are “wise” understand “dark is right,” yet the poem argues against this acceptance.

Language and Tone

- Imperatives: The poem is urgent and commanding, brimming with imperatives like “Do not go,” “Rage,” “Curse,” and “Bless.” The speaker isn’t merely observing death, he’s demanding action and resistance.

- Sound Devices: Thomas employs rich sound devices like alliteration (“frail deeds…danced”) and assonance (“Grave men…blinding sight”), creating a musical texture that enhances the emotional impact.

- Passionate Tone: The overall tone is intensely passionate, even desperate. There’s pleading, anger, and defiance intermingled, reflecting the complex emotions tied to death and the intense desire to fight against it.

Themes

The Fight Against Mortality

The poem’s core focus is the fierce, unwavering defiance against the inevitability of death.

Thomas rejects the idea of accepting the end passively and instead argues for a passionate struggle to hold on to life. This is not a struggle born from a simple fear of death, but rather an affirmation of life’s preciousness.

Through his evocative imagery and repetition of the refrain “rage, rage against the dying of the light,” the speaker emphasizes that the true value of existence lies in the very act of fighting for it.

Even if all lives must ultimately end, the intensity of that struggle transforms death from a mere surrender into a dramatic stand against the natural order.

The Power of Deeds and Legacy

The poem explores the idea that our actions leave an enduring imprint on the world.

It references different types of men – wise, good, wild, and grave – to illustrate that regardless of the path taken in life, the most profound regret near death is for the things left undone.

This suggests that a life well-lived is one where actions, words, and passions have been fully expressed. In their final struggle against death, these individuals rage not only for the loss of their own existence but also for the potential left unfulfilled.

The poem reminds us that our legacy resides in the impact we make while we are alive, and it is in this lasting mark that we can partially transcend the finality of death.

The Universal Nature of the Struggle Against Death

Thomas emphasizes that the fight against death is not bound by personality, wisdom, or how one has lived. The poem’s careful use of archetypes – the wise man, the good man, the wild man, and the grave man – demonstrates a universality to this struggle.

No matter one’s disposition or choices in life, the raw, primal desire to cling to existence unites us all.

The poem asserts that in the face of mortality, every individual experiences a profound desire to push back, to hold on to those fleeting moments of light.

The Transformative Power of Grief and Love

While the poem’s surface message is a fight against death, it’s also a poignant exploration of a son grappling with his father’s impending mortality.

The speaker’s passionate pleas and repeated command, “Do not go gentle…”, can be seen as expressions of both profound love and deep-seated grief. Their desperation to “curse” and “bless” reflects the complex emotions of a person facing loss.

These emotions fuel the speaker’s defiance against death, transforming his struggle into a desperate act of love, a final attempt to hold on to the connection with his fading father.

Final Thoughts

“Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” isn’t simply a poem about confronting death; it’s a battle cry. It challenges our notions of mortality and reminds us that the value of life lies in its very fragility.

The act of living, of resisting the darkness until the very last breath, is endowed with a profound and defiant beauty.