Sociopath: A Memoir Summary, Analysis and Themes

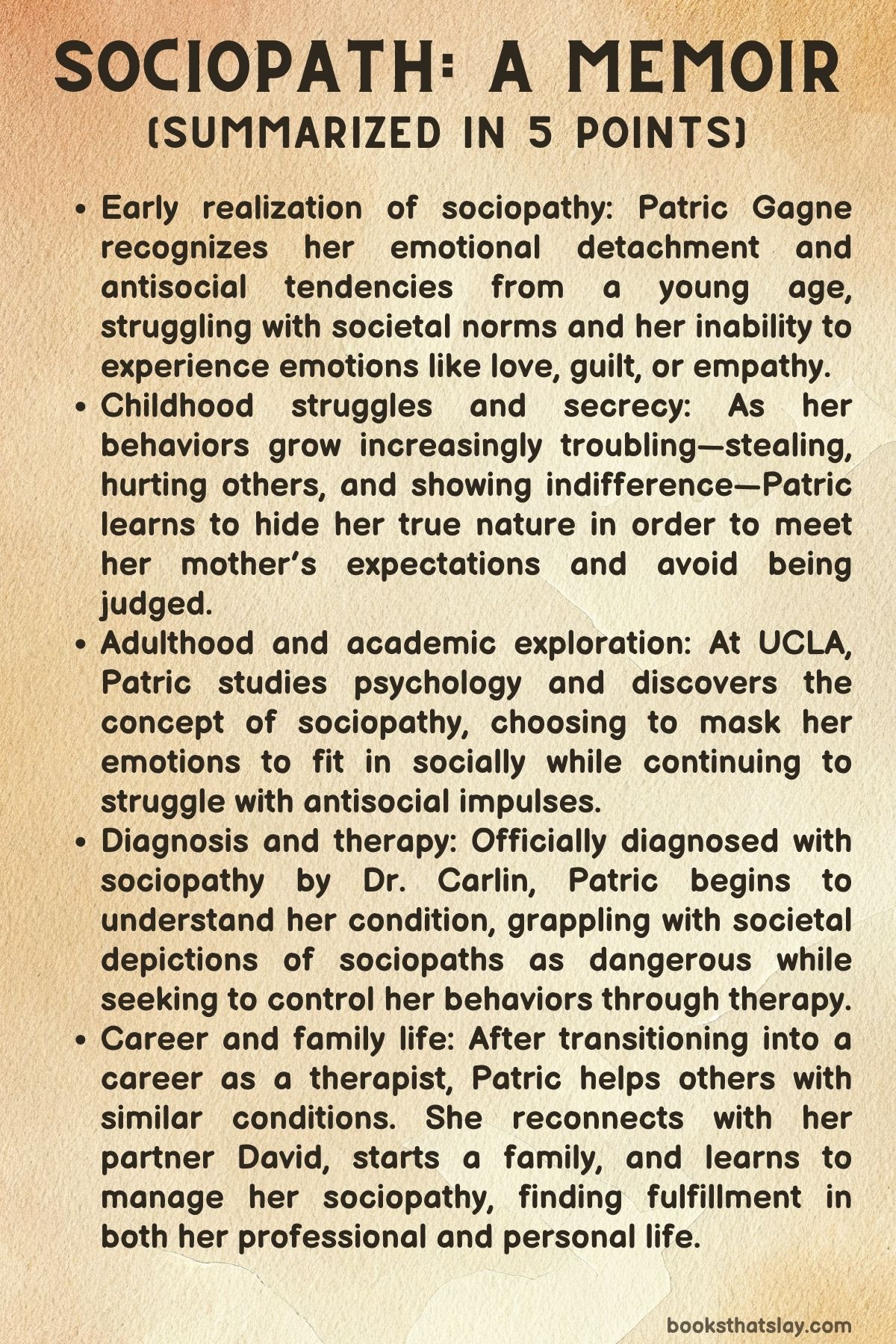

Sociopath: A Memoir (2024) by Patric Gagne offers a candid and rare insight into the life of someone living with sociopathy. Through a deeply personal lens, Gagne recounts her experiences from childhood to adulthood, navigating a world that often misunderstands and vilifies people like her.

With her unique emotional detachment and antisocial tendencies, Gagne’s journey takes her through academia and into a career as a therapist. The memoir presents her quest for self-acceptance, revealing how she confronts the challenges of sociopathy while searching for connection, purpose, and a sense of belonging in a judgmental society.

Summary

By the age of seven, Patric Gagne realizes she doesn’t process emotions like her peers. She feels happiness and anger but lacks “social emotions” such as empathy, guilt, or love. Her emotional indifference leads her to commit troubling acts, like stealing items, which she keeps in a secret box.

Her mother grows increasingly concerned as Patric’s behavior escalates, including locking her friends outside at night or even stabbing a classmate with a pencil in a moment of cold detachment. While her mother stresses honesty, Patric feels the only way to navigate her emotions is to suppress her truth.

After her parents’ separation, Patric, her mother, and sister relocate to Florida. Despite the move, Patric’s emotional unresponsiveness remains. A near-abduction incident doesn’t scare her, and her indifference is revealed when she cruelly squeezes a stray cat’s neck out of sheer compulsion.

A visit to her uncle’s prison introduces her to the concept of sociopathy, sparking a curiosity that leads her to suspect she might be one. When her beloved pet ferret dies, Patric feels nothing, triggering an internal conflict between her lack of emotion and societal expectations.

Her family’s reactions alienate her further, and she learns that in order to fit in, she must start hiding her true self.

During her teenage years, Patric’s compulsions continue, though she makes rules to avoid hurting others. She sneaks into homes her mother, a realtor, has access to, and spends her time stalking people she finds intriguing.

Though making friends remains difficult, a summer romance with a boy named David offers Patric her first taste of companionship. His emotional openness provides a contrast to her emotional void, and his understanding nature strengthens their bond.

At UCLA, Patric begins to study psychology in an attempt to make sense of her own sociopathy. She decides to mimic others’ emotional behaviors, becoming more socially accepted in the process.

However, her compulsive behaviors persist, like stealing car keys at parties. Her research into sociopathy is largely disheartening, offering bleak prospects for people like her.

A failed suicide attempt forces Patric to confront her own hopelessness.

Eventually diagnosed as a sociopath by Dr. Carlin, Patric is relieved to have a name for her condition, though societal depictions of sociopaths as inherently evil trouble her.

While working in the music industry, she befriends colleagues who exhibit similar traits but realizes that some use sociopathy as a convenient excuse for unethical behavior, causing her internal conflicts.

Patric and David’s relationship resumes but becomes strained by her continued transgressions. Patric, seeking control over her life, begins therapy and starts developing strategies to manage her impulses.

Over time, she shifts careers, focusing on helping others with similar conditions. She eventually finds fulfillment in her role as a therapist, and after rekindling her relationship with David, the two start a family. Though initially, she struggles to connect with her children, Patric learns to love them.

With her memoir, Patric hopes to challenge misconceptions about sociopathy and offer a sense of solidarity to others like her.

Characters

Patric Gagne

Patric is the central character and narrator of the memoir, offering a unique perspective on sociopathy by sharing her personal journey from childhood to adulthood. From an early age, Patric exhibits behaviors that distinguish her from her peers, most notably her lack of “social emotions” such as empathy, guilt, and shame.

She acknowledges experiencing emotions like happiness and anger but feels disconnected from the feelings that society values. Her apathy drives her toward antisocial behaviors, yet her intellectual curiosity and desire to understand herself lead her to pursue a career in psychology.

Throughout the memoir, Patric is portrayed as a complex character who straddles the line between societal norms and her internal reality. Her actions—like stealing, spying, and even moments of violence—are often driven by her compulsion to test boundaries or experience a sense of peace that comes from breaking rules.

Despite these tendencies, Patric shows a deep desire for connection and understanding, which culminates in her relationship with David and her eventual decision to become a therapist. Over time, she learns to navigate her condition, faking emotions and copying behaviors to fit in socially.

The narrative shows her growth as she moves from self-isolation toward self-awareness, discovering ways to manage her sociopathy without completely losing her individuality.

Mrs. Gagne (Patric’s Mother)

Mrs. Gagne plays a significant role in Patric’s development, being both supportive and overwhelmed by her daughter’s behavior. She is portrayed as a compassionate yet firm figure, emphasizing honesty in her attempts to help Patric, despite not fully understanding the nature of her daughter’s condition.

Her distress is palpable as Patric’s behavior escalates, yet she continuously seeks ways to help her daughter conform to societal norms. Mrs. Gagne’s love for Patric is evident, but her inability to connect with her emotionally causes strain in their relationship.

Her idea of sending Patric to boarding school, along with the burial of Baby (the ferret) without Patric, illustrates the growing distance between mother and daughter as Patric’s lack of emotional responses alienates her further from her family.

David

David serves as a crucial figure in Patric’s life, representing her first real connection to another person who does not judge her for her sociopathic tendencies. Described as kind and empathetic, David embodies the qualities Patric lacks but deeply admires.

Their relationship is one of mutual respect and understanding, though it is also fraught with tension due to Patric’s inability to feel the same range of emotions. David’s patience with Patric makes him an anchor in her life, but their relationship ultimately fails because of the limitations imposed by Patric’s sociopathy.

Despite their eventual breakup, David’s influence on Patric remains profound, as he introduces her to the possibility that she can exist in a world governed by emotions, even if she doesn’t naturally share them.

Dr. Carlin

Dr. Carlin is Patric’s psychologist and a pivotal character in her journey toward self-acceptance. As the person who officially diagnoses Patric as a sociopath, Dr. Carlin helps her understand her condition in a more clinical and structured way.

Rather than viewing Patric’s sociopathy as something to “cure,” Dr. Carlin guides her toward strategies for managing it, encouraging her to consider graduate school and writing a book to help others like her. Dr. Carlin’s approach is rooted in acceptance and adaptation, offering Patric an alternative to the destructive behaviors she might otherwise engage in.

He helps her find a balance between her darker tendencies and her desire for a functional, fulfilling life. Under his guidance, Patric begins to see her sociopathy not as an inherent evil but as a condition she can work with.

Harlowe (Patric’s Sister)

Harlowe, though not as prominently featured as some other characters, provides an additional lens through which Patric’s behavior is observed. As Patric’s younger sister, Harlowe represents innocence and conventional emotional attachment, contrasting sharply with Patric’s emotional detachment.

Harlowe’s reactions to Patric’s behavior are often indirect, seen through Mrs. Gagne’s concerns for both daughters. The familial tension caused by Patric’s inability to form strong emotional bonds likely affects Harlowe, though this is not deeply explored.

Her presence in the narrative underscores the normalcy that Patric struggles to conform to.

Jennifer

Jennifer is one of Patric’s colleagues in the music industry and represents a more negative aspect of sociopathic behavior. Unlike Patric, who strives to control her antisocial impulses, Jennifer uses sociopathy as a justification for her immoral actions.

Jennifer’s casual indifference to her dog’s vicious attack on a neighbor’s pet marks a turning point for Patric, who becomes horrified at how Jennifer misuses the label of sociopath to excuse cruelty. This moment of moral conflict drives Patric to break into Jennifer’s home, highlighting the tension Patric feels between her own sociopathic tendencies and her growing awareness of the consequences of unchecked antisocial behavior.

Jennifer serves as a foil to Patric, showing the potential darkness that can come with sociopathy if left unexamined or misused.

Arianne

Arianne is Patric’s friend who manipulates her into using her sociopathic tendencies for personal gain. She convinces Patric to break into Jacob’s house and read his journal, exploiting Patric’s lack of guilt or fear regarding such transgressions.

However, Patric eventually feels betrayed by Arianne’s manipulation, as she begins to realize that her condition makes her vulnerable to being used by others. Arianne’s role in the memoir is important as it highlights how Patric’s sociopathy can be both a shield and a vulnerability, leaving her open to exploitation by those who understand her weaknesses.

Max Magus

Max Magus, a singer Patric befriends, represents another type of sociopath who embraces the darker aspects of the condition. Max encourages Patric to indulge in her antisocial impulses, which puts him in direct conflict with the more moderated path she begins to follow with Dr. Carlin’s help.

His anger at Patric when she rejects him reveals his inability to handle emotional rejection, underscoring his own destructive tendencies. Max’s influence on Patric is a reminder of the allure that the sociopathic mindset can have, especially when it promises freedom from societal constraints.

Ultimately, he serves as a cautionary figure that Patric moves away from as she seeks a more balanced life.

Ginny Krusi

Ginny Krusi is a secondary antagonist in the memoir, acting as a catalyst for Patric’s internal conflict between her desire for revenge and her commitment to control her sociopathic urges. Ginny’s extortion of Patric, using compromising photographs of her father, sets off a chain of events where Patric must wrestle with the temptation to act on her darker impulses.

Patric’s near-violent encounter with Ginny shows her struggle to maintain control over her sociopathic tendencies. Her ultimate decision to resist aggression is a testament to her personal growth.

Ginny functions as a test for Patric’s evolving sense of morality and her ability to live with her condition.

Themes

The Conflict Between Intrinsic Apathy and Societal Emotional Expectations

A dominant theme in Sociopath: A Memoir is the tension between Patric Gagne’s innate apathy and the emotional norms imposed by society. From an early age, Gagne recognizes that she does not experience the same emotional responses as others, particularly with regard to emotions deemed necessary for social cohesion, such as love, empathy, guilt, and shame.

This sets up a lifelong internal struggle for Gagne, who must navigate a world where her lack of these emotions is pathologized and viewed as morally deficient. The memoir details how this apathy manifests in her everyday life and her interactions with others, creating a persistent dissonance between her personal reality and the expectations of the world around her.

Society’s labeling of her as “bad” or “dangerous” exacerbates her feelings of alienation, but as she matures, Gagne learns to manage her apathy strategically. She adopts the guise of normalcy to evade punishment and rejection, presenting the conflict between a true sense of self and the societal demands for conformity as a central issue in her life.

The Ethics of Self-Regulation and Boundary Transgressions in the Sociopathic Experience

One of the most complex and nuanced themes in Gagne’s memoir is the ethical dimension of how a sociopath navigates personal impulses to transgress social boundaries. Gagne’s story demonstrates that while sociopaths may lack traditional moral emotions, this does not imply that they are incapable of developing their own ethical framework.

Early in her life, Gagne’s actions, such as stealing or hurting others, reflect her difficulty in adhering to social boundaries. However, as she grows older and understands her condition more deeply, she sets personal rules to limit harm to others, illustrating the possibility of self-regulation without the usual emotional incentives of guilt or shame.

The narrative complicates the traditional binary of moral versus immoral behavior by portraying Gagne’s deliberate and thoughtful process of controlling her sociopathic urges. Her decision to continue breaking into homes, for example, but without causing harm, and her use of the Statue of Liberty keychain to signal her boundary transgressions to David, reveal an evolving ethical framework that is not dependent on conventional morality but rather on pragmatic choices that align with her unique psychological reality.

Love as a Paradoxical Force in the Life of a Sociopath: Between Illusion and Genuine Transformation

The memoir explores the paradox of love in the life of a sociopath, positioning it both as an elusive ideal and as a force capable of genuine transformation. Gagne’s relationship with David plays a pivotal role in this theme, as it symbolizes her quest to experience and understand love in a way that feels authentic despite her emotional limitations.

Initially, Gagne believes that love, particularly her relationship with David, can “cure” her sociopathy, but over time, she learns that her understanding of love is more complex and multifaceted. The narrative challenges the common perception that sociopaths are incapable of love by showing how Gagne gradually develops deep attachments to David and later her children.

Yet, this love is not spontaneous or immediate, as it might be for others; it requires intellectual effort and conscious decision-making. The theme of love, therefore, is portrayed as both a transformative and frustrating force in Gagne’s life, revealing the tension between her desire for normalcy and her acceptance of her inherent emotional differences.

The Intersection of Sociopathy and Gendered Expectations of Emotional Labor

Gagne’s experiences also touch on the theme of how sociopathy intersects with gender, particularly the expectations placed on women to perform emotional labor and embody nurturing roles. As a woman diagnosed with sociopathy, Gagne is doubly marginalized: she defies both the societal standards of emotional engagement expected of all individuals and the gendered expectations that women, in particular, must be caring, empathetic, and self-sacrificing.

Her lack of maternal instinct upon the birth of her first child challenges deeply ingrained cultural beliefs about motherhood, where women are often assumed to feel an overwhelming sense of love and protectiveness for their children. The memoir presents Gagne’s struggle with motherhood not as a failure but as an alternative path to emotional connection—one that involves learning to love through a process of intellectual engagement rather than through innate emotional responses.

This theme raises important questions about how women who do not conform to traditional emotional roles are judged and how they navigate the societal pressures to adhere to those roles.

The Sociopath as a Construct of Medical, Cultural, and Popular Discourses: Between Pathology and Human Variation

A central intellectual theme in the memoir is the critique of how sociopathy is constructed through medical, cultural, and popular narratives. Gagne’s exploration of the term “sociopath” and her subsequent diagnosis with antisocial personality disorder highlights the disconnect between personal lived experience and clinical definitions.

The memoir critically examines how the medical community has shifted its understanding of sociopathy, from a more nuanced concept to its rebranding as antisocial personality disorder (ASPD), which comes with a set of rigid and often stigmatizing criteria. Moreover, Gagne reflects on how sociopaths are depicted in mainstream culture, frequently characterized as irredeemable villains or emotionless monsters, which further alienates individuals like herself who do not fit into these one-dimensional portrayals.

The memoir challenges the reader to reconsider sociopathy not as an incurable pathology but as part of the diversity of human emotional and cognitive experiences. By doing so, it opens a space for questioning the ethical implications of diagnosing and labeling individuals based on neurodiversity and emotional nonconformity.

The Therapeutic Process as a Medium for Redefining Self and Building New Emotional Paradigms

Another theme that emerges strongly in the memoir is the transformative role of therapy in helping Gagne redefine her sense of self and build new paradigms for emotional understanding. The therapeutic relationship with Dr. Carlin is depicted as crucial not only in helping Gagne come to terms with her diagnosis but also in encouraging her to forge her own path toward self-management.

The memoir portrays therapy not as a cure but as a means of equipping individuals like Gagne with tools to better navigate a world that demands emotional conformity. Gagne’s eventual decision to become a therapist herself reflects her belief in the value of therapy as a medium for change, not in eradicating sociopathy, but in helping sociopaths create functional emotional frameworks.

Through this lens, therapy is reframed as a dynamic process that allows individuals to engage with their emotional differences in constructive ways, enabling personal growth and broader societal understanding of emotional diversity.