Raybearer Summary, Characters and Themes

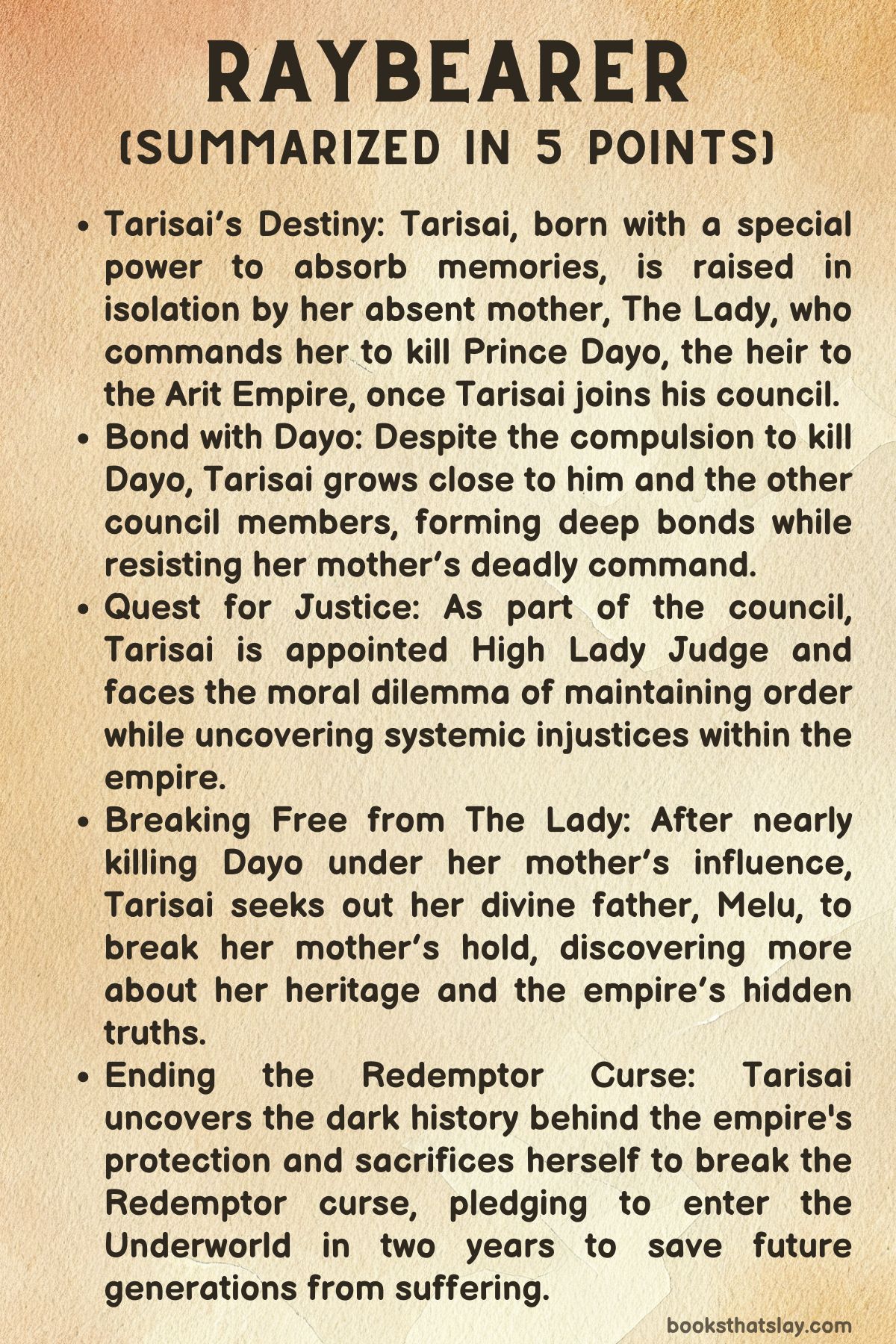

Raybearer, published in 2020, a young adult fantasy novel by Jordan Ifueko, immerses readers in a richly textured world inspired by West African folklore. The story follows Tarisai, a girl burdened by her past and born with a dangerous destiny. Raised in isolation, she is sent to join the Council of an imperial prince, bound by magic and duty.

But with her mother’s dark wishes compelling her to assassinate the prince, Tarisai must find a way to break free from her inherited fate. This gripping debut explores themes of family, loyalty, justice, and self-determination, with strikingly diverse characters and vivid world-building.

Summary

Tarisai grows up in Swana, part of the vast Aritsar Empire, isolated within Bhekina House under the care of servants and tutors. Her mother, known only as The Lady, is an absent yet controlling figure. Tarisai possesses a rare ability to extract memories from people or objects, which makes her interactions limited.

One night, Tarisai sneaks out and meets Melu, a deity trapped by The Lady and forced to grant her wishes. Through Melu’s memories, Tarisai learns that she is his daughter, conceived through The Lady’s wish to bear a child destined to kill the Emperor’s son, Prince Dayo.

Soon after, The Lady returns with two companions, Woo In and Kathleen, and orders them to take Tarisai to the imperial capital, Oluwan.

Before they leave, The Lady reveals a portrait of Prince Dayo and commands Tarisai to kill him once she is accepted into his council. Because of Tarisai’s half-ehru heritage, she is magically compelled to obey her mother’s commands.

Upon arriving in Oluwan, Tarisai enters the Children’s Palace, where Dayo and his future council are being selected. She befriends Kirah, a healer, and Sanjeet, a former pit fighter. Tarisai is conflicted as she bonds with Dayo, knowing that one day she will be forced to harm him.

The Emperor’s Council is suspicious of Tarisai, given The Lady’s past, but she becomes one of the final candidates for Dayo’s council.

Years pass, and Tarisai grows closer to Dayo, resisting her mother’s order to kill him. But The Lady’s impatience grows, and Woo In starts a fire in the palace to push events forward. Tarisai rescues Dayo, realizing that her feelings for him run deeper than duty. She decides to join his council, gaining immunity through their magical bond.

As Tarisai assumes her duties as part of the Prince’s council, tensions rise when the abiku, demons of the Underworld, demand the Redemptor debt be repaid, leading to a violent attack.

Tarisai learns about the Redemptors, children from Songland sacrificed to keep the empire safe. As the next High Lady Judge, she grapples with injustice, realizing that the empire’s unity comes at the cost of erasing local traditions and stories.

Things take a darker turn when The Lady returns, disguised as an elder, and restores Tarisai’s forgotten memories. Tarisai is forced to follow her mother’s command and nearly kills Dayo in a fit of compulsion.

With Sanjeet’s help, she escapes to Swana to seek out Melu and find a way to break free from The Lady’s hold.

In Swana, Tarisai uncovers secrets about her mother’s past, including her Raybearer heritage and betrayal by the Emperor. With Sanjeet’s support, Tarisai embarks on a quest to retrieve the lost masks of the empire’s empress and princess, critical to restoring balance.

As political intrigue unravels, Tarisai must confront her mother, who dies after a series of tragic events, leaving the empire vulnerable.

The novel concludes with Tarisai learning the true history of Aritsar’s blood-soaked Treaty of the Underworld. In a daring move, she negotiates with the abiku, offering her own life in exchange for ending the cruel cycle of Redemptor sacrifices.

She secures peace, but her journey into the Underworld still looms ahead, as she has two years left to fulfill her destiny.

Characters

Tarisai Idajo

Tarisai is the protagonist of the novel, and her character is defined by the tension between her inherited destiny and her personal desires. From a young age, Tarisai grapples with the knowledge that she was conceived with the purpose of fulfilling her mother’s ambitions.

This pressure to obey her mother’s command to kill Prince Dayo dominates much of her internal struggle. Tarisai’s journey revolves around her desire for autonomy and freedom from the controlling forces of her mother, The Lady.

Her unique power of “taking” stories from others underscores her sensitivity to people’s emotions and histories. This ability emphasizes her empathy, which eventually leads her to seek justice and fairness as the High Lady Judge.

Tarisai’s moral compass compels her to question the unjust structures of the empire, especially as they relate to the Redemptor curse. She matures into a figure willing to sacrifice her own soul for the greater good.

Her bond with Dayo evolves from a sense of duty to genuine affection. Her struggle to resist The Lady’s control is central to her character’s emotional and psychological growth.

The Lady (Tarisai’s Mother)

The Lady is a complex antagonist, driven by a thirst for power and revenge. Her motivations are rooted in the pain of her past, particularly her banishment from the imperial council due to her brother’s jealousy.

The Lady’s manipulation of Tarisai, having orchestrated her daughter’s birth to fulfill her ambitions, reveals her as a character willing to sacrifice her child’s agency for her vendetta. The Lady’s use of Melu to create Tarisai and her continued influence over her daughter’s life showcase her immense control.

Her actions are driven by a deep-seated desire to correct the wrongs she perceives were done to her. Her death at the end of the novel, brought on by Woo In’s realization of her betrayal, marks the culmination of her tragic arc.

Despite her power and ruthlessness, The Lady ultimately succumbs to the consequences of her own deception. Her selfishness becomes her undoing.

Prince Ekundayo (Dayo)

Prince Dayo represents a figure of innocence and hope within the novel. Despite being born into the pressures of royalty, Dayo possesses a genuine kindness and compassion that draws others, particularly Tarisai, to him.

His deep connection to his council and belief in unity reflect his idealism. Dayo’s vulnerability is a key part of his character, especially as he lacks the immunity the council must provide him.

While Dayo appears as a figure of peace and reconciliation, his relationship with Tarisai complicates his position. He unknowingly places himself in mortal danger due to Tarisai’s mother’s wishes.

Despite this, his relationship with Tarisai develops into a close bond based on mutual trust. His capacity to forgive and empathize becomes one of his greatest strengths as a ruler.

Sanjeet

Sanjeet’s character highlights themes of resilience and loyalty. His traumatic past as a pit fighter, subjected to abuse by his father, shapes him into a physically strong but emotionally wounded individual.

He forms a strong connection with Tarisai, and their growing affection provides a counterbalance to the darker aspects of their lives in the imperial palace. Sanjeet’s loyalty is a defining feature, and he stands by Tarisai through her struggles with her mother.

He later accompanies her on her journey to Swana to uncover the truth about her past. His relationship with Tarisai is characterized by support and understanding, and their eventual romance is marked by tenderness.

Sanjeet’s character arc shows his growth from a survivor of abuse to a loyal companion and romantic partner. He solidifies his importance in the story as a source of strength and healing.

Woo In

Woo In is one of the most enigmatic characters in the novel, with his origins in Songland setting him apart from others in the imperial court. As a Redemptor, Woo In carries the weight of his survival through the Underworld and the accompanying trauma.

His tattoos serve as a physical reminder of the immense burden he bears as part of Songland’s role in the Treaty with the abiku demons. Woo In’s relationship with Tarisai is initially ambiguous, as he is sent by The Lady to manipulate her.

Over time, his own conflicted loyalties and deep sense of injustice become apparent. Woo In’s realization of The Lady’s betrayal and his subsequent actions are driven by a fierce desire to free his people from the Redemptor curse.

His eventual alliance with Tarisai and willingness to risk everything to break the Redemptor curse demonstrate his evolution. He transforms from a mysterious figure with divided loyalties to a hero fighting for his people’s freedom.

Kirah

Kirah represents a nurturing and compassionate presence within the novel. She forms a close friendship with Tarisai during their time as candidates for Dayo’s council, and her kindness and healing abilities provide comfort amidst the political turmoil.

Kirah’s role is crucial in supporting Tarisai emotionally, especially when Tarisai struggles with the burdens placed upon her. Although Kirah’s abilities are not combative, her healing gift is symbolically important in a world fractured by political schemes and violence.

Her friendship with Tarisai highlights the value of loyalty and mutual support. Her presence in the narrative serves as a reminder of the importance of compassion and care in the face of adversity.

Melu

Melu, the deity who becomes The Lady’s ehru, plays a significant role as both a father figure and a symbol of captivity. His relationship with Tarisai is complex, as he is both her father and the victim of The Lady’s manipulation.

Melu’s enslavement by The Lady, who uses his powers for her own gain, reflects the theme of control and exploitation in the novel. Despite his limited influence, Melu’s revelations about Tarisai’s origins are crucial in her understanding of her identity.

Melu represents a tragic figure in the story, trapped by The Lady’s greed and unable to protect his daughter from manipulation. His role in the narrative as a source of knowledge and truth helps Tarisai come to terms with her heritage and break free from her mother’s control.

Thaddace

Thaddace, a member of the Emperor’s council and the High Judge before Tarisai, represents the rigid and authoritarian aspect of the empire’s legal system. His insistence on prioritizing order over fairness contrasts with Tarisai’s values.

Their philosophical differences about justice become a focal point in the novel. Thaddace’s Unity Edict, which seeks to erase the unique cultural identities of the different realms in the name of unity, reflects his belief in maintaining control.

His involvement in the illicit affair with Mbali further complicates his character, revealing his hypocrisy and flaws. Thaddace’s downfall comes when he inadvertently causes the Emperor’s death, marking the end of his rigid hold on power.

This moment symbolizes the fall of the old order that Tarisai seeks to reform. His character reflects the dangers of prioritizing control over justice.

Themes

The Complex Interplay of Kinship, Power, and Identity in a Matriarchal Context

In Raybearer, Jordan Ifueko delves into a nuanced exploration of kinship, not merely as a familial bond but as a system intertwined with power, obligation, and individual identity. Tarisai’s relationship with her mother, The Lady, is fraught with manipulation, betrayal, and control, which shifts the traditional understanding of maternal love.

The Lady’s role as a matriarch is not one of nurturing, but one of imposing her will, with Tarisai functioning as a tool to exact revenge on the empire. This matriarchal power dynamic raises questions about the nature of kinship, especially when it is rooted in magical and coercive ties rather than voluntary, emotional bonds.

Tarisai’s journey is thus not only one of seeking personal identity but also a desperate quest to redefine what kinship means—moving away from The Lady’s conditional, toxic love to form genuine connections with Dayo and the other council members. Ifueko challenges the reader to consider how power structures within families can distort traditional roles, turning them into tools of domination rather than support.

This conflict between inherited identity and self-determined destiny forms the emotional and thematic core of the novel, with Tarisai grappling with her ehru lineage and the powerful compulsion it imposes on her life.

Justice as Liberation and the Tension Between Fairness and Order

The theme of justice in Raybearer is a multifaceted one, engaging with both the legal and the moral dimensions of governance. Ifueko presents a legal system deeply intertwined with tradition, where justice is often sacrificed in favor of maintaining order.

This tension is personified in Tarisai’s role as the High Judge, a position that forces her to navigate the balance between upholding imperial edicts and her personal understanding of fairness. Thaddace’s insistence that order should take precedence over fairness reflects the entrenched power structures of the Arit empire, where maintaining the status quo often supersedes the rights and stories of individuals.

Tarisai, however, represents a new kind of justice—one that seeks to disrupt these structures in favor of inclusivity and moral fairness. Her revocation of the Unity Edict is not just an act of legal reform but a symbolic rejection of the erasure of cultural identities and stories.

The novel asks difficult questions about who gets to define justice in a society and whether justice can truly exist when it is dictated by those in power. Tarisai’s vision of justice is one that seeks liberation from the limitations imposed by history and tradition, positioning her as a revolutionary figure who is willing to challenge even the most sacred of imperial laws.

The Burden of Historical Trauma and the Quest for Cultural Restoration

Ifueko intricately weaves the theme of historical trauma throughout Raybearer, presenting it not only through personal histories but also through the collective history of the empire. The Ray, a psychic bond that ties the emperor’s council together, functions as a metaphor for the heavy weight of history and the trauma that binds people across generations.

The empire of Aritsar itself is a manifestation of historical violence—founded on treaties like the one with the abiku demons that demand the sacrifice of Redemptor children. This history of exploitation is a recurring trauma for characters like Woo In and Tarisai, both of whom grapple with the roles their lineages play in this cycle of violence.

Tarisai’s quest is not only one of personal freedom but also one of cultural restoration, as she seeks to recover the lost traditions and masks of the empress and princess, symbols of a forgotten balance in the empire’s rule. This search for cultural restoration ties into the broader theme of reclaiming stories and identities that have been suppressed or erased by imperial forces.

Ifueko uses Tarisai’s journey to explore how individuals and societies can begin to heal from historical trauma, but she does not offer easy answers. Instead, the novel suggests that such healing requires both personal sacrifice and systemic change, as embodied in Tarisai’s eventual decision to sacrifice herself to break the Redemptor curse and restore balance to the empire.

The Intricacies of Compulsion and Free Will in Magical and Political Power

One of the most profound themes in Raybearer is the conflict between compulsion and free will, both in the magical and political sense. Tarisai’s journey is defined by her struggle to resist the compulsion placed on her by her mother, The Lady, whose wishes Tarisai is bound to fulfill because of her ehru heritage.

This magical form of compulsion acts as a metaphor for the political structures in place within the empire, where individuals are similarly bound by their roles within a rigid hierarchy, often with little autonomy. The Ray, while allowing for a deep psychic connection between council members, also serves to bind them to the emperor, creating a system in which personal desires are subsumed by the greater political order.

Ifueko masterfully blurs the lines between magical influence and political control, using Tarisai’s internal conflict to question whether true free will can exist in a system that demands obedience, whether through magical ties or imperial edicts. Tarisai’s eventual rejection of her mother’s compulsion is not only a personal victory but also a political one, as she asserts her right to choose her own path and, by extension, seeks to reform a political system that similarly forces its subjects into predefined roles.

This theme speaks to the broader question of autonomy and how individuals can reclaim agency in systems of control, whether they are magical, familial, or political in nature.

The Intersection of Empire, Cultural Imperialism, and Resistance Through Storytelling

Ifueko’s Raybearer is also a meditation on the dynamics of empire and cultural imperialism, particularly how the Arit empire imposes its narratives, laws, and values on its subject realms. The Unity Edict, which Thaddace enforces to erase the unique stories and traditions of the empire’s diverse regions, is an explicit metaphor for cultural imperialism.

By requiring all the realms to renounce their distinct identities, the empire seeks to homogenize its population under a single, imperial narrative. Tarisai’s revocation of this edict is a form of resistance not only to imperial law but also to the broader cultural erasure that accompanies empire.

Through this, Ifueko examines the power of storytelling as both a tool of imperial control and a means of resistance. The stories that Tarisai inherits—both personal and cultural—shape her identity, but it is only when she reclaims her own narrative, free from the constraints of her mother and the empire, that she is able to assert her true power.

The novel thus positions storytelling as a form of rebellion, a way for individuals and cultures to resist assimilation and maintain their unique identities in the face of imperial domination.

This theme underscores the broader conflict in the novel between preservation and erasure, asking readers to consider how stories—whether personal, cultural, or historical—can be wielded as both tools of oppression and weapons of liberation.