The Paris Novel Summary, Characters and Themes

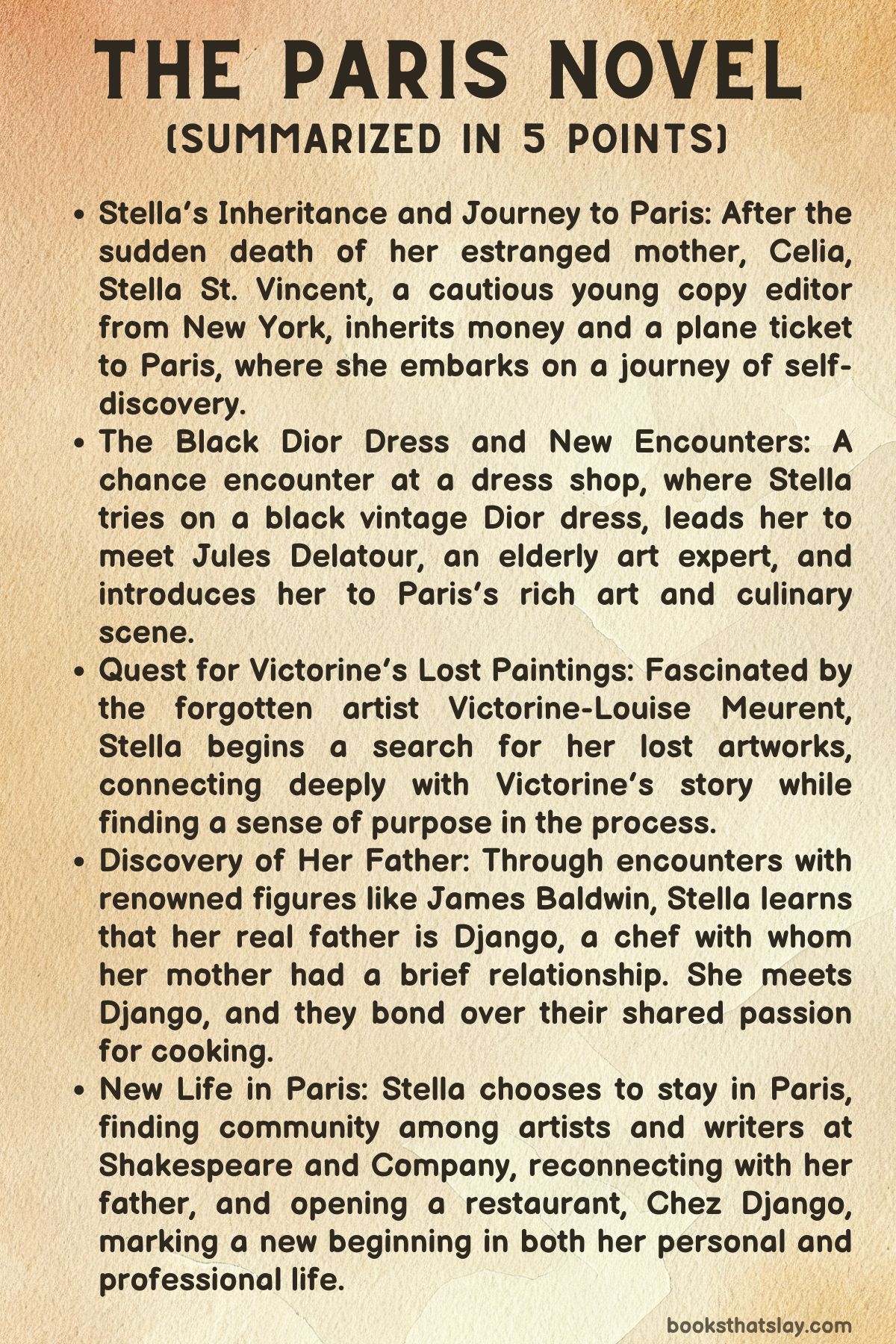

The Paris Novel by Ruth Reichl is a captivating story of self-discovery, set against the vibrant backdrop of 1980s Paris. It follows Stella St. Vincent, a young copy editor from New York City, whose life takes an unexpected turn when her estranged mother passes away, leaving her a plane ticket and money to visit Paris.

What begins as a reluctant trip soon becomes a journey of artistic exploration, personal growth, and reconnection with her past. Immersed in the rich culture of Paris, Stella finds new passions, forms deep bonds, and uncovers forgotten stories that help her embrace a life she never imagined.

Summary

Stella St. Vincent is a cautious, introverted copy editor living in New York City, her life defined by routines and careful control.

She carries emotional scars from a traumatic childhood event, and her relationship with her distant mother, Celia, was always strained. When Celia suddenly dies, Stella is left with not only an inheritance but also a plane ticket to Paris—a destination her mother seems to have wanted her to visit.

Initially reluctant, Stella sets off for Paris, her methodical habits intact as she plans to stick to a tight budget and a regimented schedule.

Early in her stay, however, a chance encounter alters her course. While browsing through a small dress shop, she’s encouraged by the shopkeeper to try on a vintage Dior dress, a striking black gown with the name “Séverine” stitched inside.

Stella briefly wears the dress, and what seems like an ordinary moment triggers a series of serendipitous events. She meets Jules Delatour, an elderly widower and art enthusiast, who introduces her to Paris’s hidden art and culinary gems.

During a visit to the Musée du Jeu de Paume, Stella becomes captivated by Edouard Manet’s Olympia and learns about the model, Victorine-Louise Meurent, who was not just a muse but an artist in her own right.

Driven by curiosity, Stella embarks on a mission to uncover Victorine’s lost works, starting with a deep dive into Parisian archives.

In the course of her search, she finds herself at Shakespeare and Company, the famed Paris bookstore. There, she meets George Whitman and becomes part of the store’s bohemian community known as “Tumbleweeds,” who live and work among the books.

As she settles into this new, creative life, Stella’s once-guarded world begins to open up. She bonds with Jules, who becomes a guide in her quest to learn more about Victorine, while also encouraging Stella to explore her burgeoning interest in cooking.

Stella’s talents begin to shine, and George Whitman, sensing her connection to Paris, urges her to investigate her father’s identity.

Her journey leads her to a series of startling revelations.

She discovers through writer James Baldwin that her mother had an affair with a renowned chef named Django, a man Stella had never known but whose existence piques her curiosity. Meanwhile, Stella’s research into Victorine’s life proves both frustrating and rewarding.

After navigating misleading accounts written by men and poring through Paris’s forgotten streets, she eventually locates Victorine’s last known home, only to find its contents destroyed.

Still, a nearby neighbor offers hope, telling Stella of a self-portrait by Victorine that had been salvaged and taken to a flea market. Stella tracks down the painting, seeing in Victorine’s strong, triumphant gaze a reflection of her own evolving self.

As Stella continues to piece together her past, she finds Django working at a Parisian restaurant.

The discovery that she has a father willing to embrace her and share his culinary world marks a new chapter in her life. Stella decides to stay in Paris, joining forces with Django to open a restaurant, Chez Django.

The novel closes with a symbolic gesture—Jules’s son presents Stella with the black Dior dress, now inscribed with her name, a testament to the new life she has claimed.

Characters

Stella St. Vincent

Stella, the protagonist of The Paris Novel, is a young woman who lives a restrained and cautious life in New York City. Her life is shaped largely by a traumatic childhood and the neglect of her mother, Celia.

As a copy editor, Stella finds comfort in structure and predictability, avoiding emotional risks and spontaneity. Her mother’s sudden death pushes her out of this familiar pattern when she inherits money and a plane ticket to Paris.

Initially hesitant, Stella’s journey to Paris is both a physical and emotional departure from her old life. In Paris, she continues to adhere to her rigid habits, symbolizing her reluctance to embrace change.

Her chance encounter with a vintage black Dior dress triggers the beginning of her transformation. Throughout the novel, Stella gradually sheds her guarded persona, allowing herself to explore the artistic and culinary worlds of Paris.

Her fascination with the lost painter Victorine-Louise Meurent serves as a metaphor for Stella’s own quest for identity. She seeks to uncover her own passions and talents.

Her journey culminates not only in finding Victorine’s lost paintings but also in discovering a sense of family and purpose when she meets her father, Django. By the end of the novel, Stella evolves into a more confident and self-assured individual, willing to take risks and embrace the unknown.

Celia St. Vincent

Celia, Stella’s mother, remains an enigmatic and haunting presence throughout the novel. Although deceased when the story begins, Celia’s neglectful parenting and strained relationship with Stella continue to affect the protagonist’s emotional state.

Celia’s decision to leave Stella money and a plane ticket to Paris can be seen as a final, somewhat cryptic attempt to push her daughter toward a life Celia perhaps wished she had embraced herself.

Despite the distance between them, it is Celia’s complicated legacy that sets Stella on the path of self-discovery. As Stella delves into her mother’s past, particularly through the lens of Celia’s relationship with Django and their shared love for art and food, she begins to understand her mother in a more nuanced way.

This evolving understanding allows Stella to reconcile with the emotional scars her mother left behind. She learns more about the aspects of Celia’s life that were kept hidden from her.

Jules Delatour

Jules is an elderly widower and art expert whom Stella meets in Paris. His introduction into Stella’s life represents a turning point, as he introduces her to the art world and becomes a close companion.

Initially, Stella is wary of Jules, but their friendship grows as he helps her navigate the Parisian art scene and aids her in the search for Victorine’s lost paintings. Jules’s role in the novel is multifaceted.

He acts as a mentor figure to Stella, guiding her both artistically and emotionally. He also has his own grief and history to contend with.

His deceased wife, Séverine, looms large in his life. His relationship with Stella becomes more complicated when it is revealed that she had worn Séverine’s dress—an unexpected connection that links Stella’s personal journey to Jules’s past.

Through their shared experiences, Jules opens up about his own vulnerabilities. Their friendship becomes mutually beneficial, as he offers Stella emotional support, while she helps him process his grief and guilt.

Victorine-Louise Meurent

Though not an active character in the novel, Victorine-Louise Meurent is central to Stella’s emotional and intellectual quest. Victorine was a model for Edouard Manet’s Olympia, but Stella uncovers that she was also an artist in her own right.

Victorine serves as a mirror for Stella—both women are undervalued, defined primarily by others, and searching for their own voice. Stella’s investigation into Victorine’s life and work symbolizes her own search for identity.

She delves into historical records, churches, and Parisian neighborhoods to piece together the story of an overlooked artist. Victorine’s forgotten legacy, especially the self-portrait Stella eventually finds, becomes a powerful symbol of reclamation and self-empowerment.

By recovering Victorine’s work, Stella metaphorically recovers her own sense of purpose and agency. This reinforces the novel’s theme of female creativity and resilience.

George Whitman

George Whitman, the owner of Shakespeare and Company, is an iconic figure in the novel who provides Stella with both a physical and metaphorical home during her stay in Paris. Shakespeare and Company serves as a refuge for artists, writers, and travelers, known as “Tumbleweeds.”

Through this environment, Stella finds a community that encourages her creative and personal growth. Whitman’s suggestion that Stella search for her father sets her on another important journey of self-discovery.

His bookstore is not just a setting for much of the novel’s action but also a symbol of intellectual and artistic freedom. It offers Stella the space to explore her passions in a supportive environment.

Whitman himself is portrayed as a wise and somewhat mysterious figure. He embodies the spirit of bohemian Paris and the possibility of reinvention.

Django

Django, Stella’s father, is a figure shrouded in mystery for much of the novel. A chef by profession, Django represents the missing piece in Stella’s personal history.

His absence has been a source of emotional confusion for her throughout her life. When Stella finally tracks him down, the initial meeting is charged with emotion, as Django learns for the first time that he has a daughter.

His deep connection to food and cooking mirrors Stella’s emerging passion for culinary arts, providing a symbolic bond that helps them form a relationship despite their years apart. Django’s inclusion in Stella’s life, and their decision to open a restaurant together, signifies a fresh start for both of them.

For Stella, it marks the completion of her journey toward self-acceptance and family reconciliation. For Django, it offers a chance at redemption, as he builds a relationship with the daughter he never knew existed.

Séverine Delatour

Séverine, though deceased, plays a significant role in the emotional undercurrents of the story. The black vintage Dior dress that first catalyzes Stella’s transformation once belonged to Séverine, Jules’s late wife.

Séverine’s legacy, particularly through the dress, links the past and present. This allows Stella to form a connection to a woman she never met but whose presence influences both Jules’s and Stella’s lives.

The revelation that Jules’s son’s fiancée had been selling Séverine’s belongings out of spite adds a layer of complexity to the novel’s themes of loss and memory. Séverine, like Victorine, is an absent figure whose influence on the living characters continues to shape their emotional landscapes.

Jean-Marie Delatour

Jean-Marie is Jules’s son and a more peripheral character in the novel. However, his role is important in understanding Jules’s emotional struggles.

The tension between Jean-Marie and his father, exacerbated by the son’s fiancée’s actions, adds familial conflict to the narrative. Jean-Marie’s final gesture of giving Stella the black Dior dress, now bearing her name, symbolizes the passing of the torch from one generation to the next.

It marks Stella’s stepping into her own identity, an important theme in the novel’s conclusion.

Themes

The Intersection of Identity, Trauma, and Self-Discovery

At the heart of Ruth Reichl’s The Paris Novel is a complex exploration of identity and self-discovery, intricately linked with Stella’s unresolved childhood trauma. Having grown up with a neglectful mother and the burden of a traumatic assault, Stella’s identity is fractured and defined by caution and routine.

Her decision to go to Paris, prompted by her mother’s unexpected death, serves as a metaphorical journey into her own psyche. In Paris, Stella’s world is expanded as she encounters figures like Jules Delatour, who challenge her existing identity and force her to question the rigid boundaries she has imposed on her life.

The discovery of Victorine Meurent’s forgotten legacy becomes a symbolic mirror for Stella’s own search for selfhood—both women are lost in history, misrepresented by the narratives of men. Stella’s attempt to uncover Victorine’s hidden artistic contributions is an attempt to reclaim her own suppressed desires, skills, and emotional truths.

Paris becomes the transformative space where Stella sheds the imposed definitions of her past and begins to construct a self based on her own terms, talents, and relationships.

Art as a Means of Historical Redemption and Female Empowerment

A pivotal theme in the novel is the role of art as both a historical corrective and a form of empowerment for women whose voices have been silenced. Victorine Meurent’s story, lost in the misogynistic accounts of male historians, parallels Stella’s own obscured existence under her mother’s neglect and society’s indifference.

By seeking out Victorine’s lost paintings, Stella is not only reclaiming history but also confronting the ways in which women’s accomplishments have been systematically erased. This theme is particularly relevant as Stella learns about Victorine through art, history, and Parisian landmarks—her journey is an act of defiance against male-dominated narratives.

Similarly, Stella’s growing passion for cooking reflects her own act of creation and reclamation, a skill that connects her to both her father and her sense of self. By the end of the novel, Stella’s decision to open a restaurant with Django solidifies her autonomy.

The discovery of Victorine’s triumphant self-portrait serves as a moment of poetic justice—a historical victory for an artist who was nearly forgotten, much like Stella’s own emergence from invisibility.

The Complexities of Parent-Child Relationships and Inherited Emotional Legacies

The novel presents an intricate exploration of parent-child relationships, particularly through the characters of Stella, her estranged mother Celia, and her absent father Django. Stella’s relationship with Celia is strained by neglect, emotional distance, and Celia’s failure to protect her during her childhood trauma.

Celia’s death serves as both a rupture and a catalyst for Stella’s transformation, as the unresolved tensions between mother and daughter propel Stella on her Parisian journey. Celia’s inheritance—both literal, in the form of money and a plane ticket, and metaphorical, in the unresolved mysteries of Stella’s father—guides Stella to Paris, where she begins to piece together the fragmented history of her parents’ relationship.

Django, the chef and absent father, complicates the theme of familial reconciliation. His emotional response to discovering that he has a daughter contrasts sharply with Celia’s neglect, offering Stella a different form of paternal love and connection.

Their eventual bonding over food, an artistic medium in itself, becomes a metaphor for healing. Culinary creation becomes a vehicle for Stella to understand and embrace her paternal heritage.

In this way, the novel presents the notion that emotional legacies, whether of neglect or love, shape identity but can also be rewritten through new relationships and self-understanding.

The Symbolism of Clothing and Transformation of Personal Identity

Clothing, particularly the black vintage Dior dress, serves as a potent symbol throughout the novel, representing both personal transformation and the weight of past lives. When Stella tries on the Dior dress with the name “Séverine” inscribed on the label, it becomes an emblem of the dualities of her journey—both the act of donning a new persona and the encounter with the past that must be reconciled.

As Stella wears the dress, her life changes through a series of unexpected encounters, each of which draws her deeper into Parisian society and her investigation into Victorine’s lost history. The fact that the dress originally belonged to Jules’s late wife adds layers of complexity to the theme: the dress becomes a conduit for Stella’s self-realization while simultaneously representing loss, memory, and the unresolved emotional lives of others.

The final act of Jules’s son giving Stella the dress with her own name on the label marks a profound transformation—Stella has fully claimed her identity, no longer haunted by the past or defined by others. The dress evolves from a symbol of inherited history into one of personal empowerment, reflecting the theme of how identity can be reshaped and re-owned.

The Role of Paris as a Liminal Space of Emotional and Creative Awakening

Paris is not merely a backdrop in The Paris Novel; it functions as a liminal space, a threshold between Stella’s old life of caution and her new existence of creative exploration and emotional risk. The city, with its vibrant history of art, literature, and revolution, represents a place where boundaries—social, emotional, artistic—can be dissolved and remade.

For Stella, Paris allows for encounters with key figures like Jules and the artistic community at Shakespeare and Company, all of whom help her navigate the fluidity between past traumas and future potential. The city’s landmarks, from the Musée du Jeu de Paume to its flea markets, symbolize both the weight of history and the possibility of uncovering forgotten or hidden truths.

Stella’s immersion into the world of art and cooking is facilitated by Paris, a city that both grounds and elevates its inhabitants, encouraging self-reinvention. Ultimately, Paris becomes a catalyst for Stella’s rebirth—a place where she can lose herself in artistic inquiry and, in doing so, find her own voice and identity.

The city’s role as a haven for marginalized and forgotten stories, particularly those of women artists like Victorine, reflects the novel’s overarching themes of reclamation, discovery, and self-determination.

Victorine’s Artistic Legacy as a Metaphor for Gendered Reclamation

The novel’s treatment of Victorine Meurent, the forgotten muse of Olympia, represents a larger narrative of how women’s histories are written and erased by the male gaze. Stella’s journey to uncover Victorine’s life and reclaim her lost paintings functions as a metaphor for the reclamation of female narratives more broadly.

Throughout history, Victorine’s accomplishments as an artist were overshadowed by her role as a model for male painters, and her personal contributions were largely ignored. Stella’s desire to restore Victorine’s legacy becomes a feminist act of rewriting history, challenging the patriarchal structures that have marginalized women’s voices and artistic labor.

This narrative of reclamation is central to Stella’s own evolution; as she delves deeper into Victorine’s world, she simultaneously uncovers her own hidden potential. The act of finding Victorine’s self-portrait, where she is depicted as self-assured and triumphant, offers a radical counter-narrative to the passive, objectified figure in Olympia.

By placing women’s stories, voices, and accomplishments at the center of the novel, Reichl not only critiques the historical erasure of women but also offers a new vision of female empowerment where the past is reclaimed and reinterpreted through the female gaze.