The Eyes Are the Best Part Summary, Characters and Themes

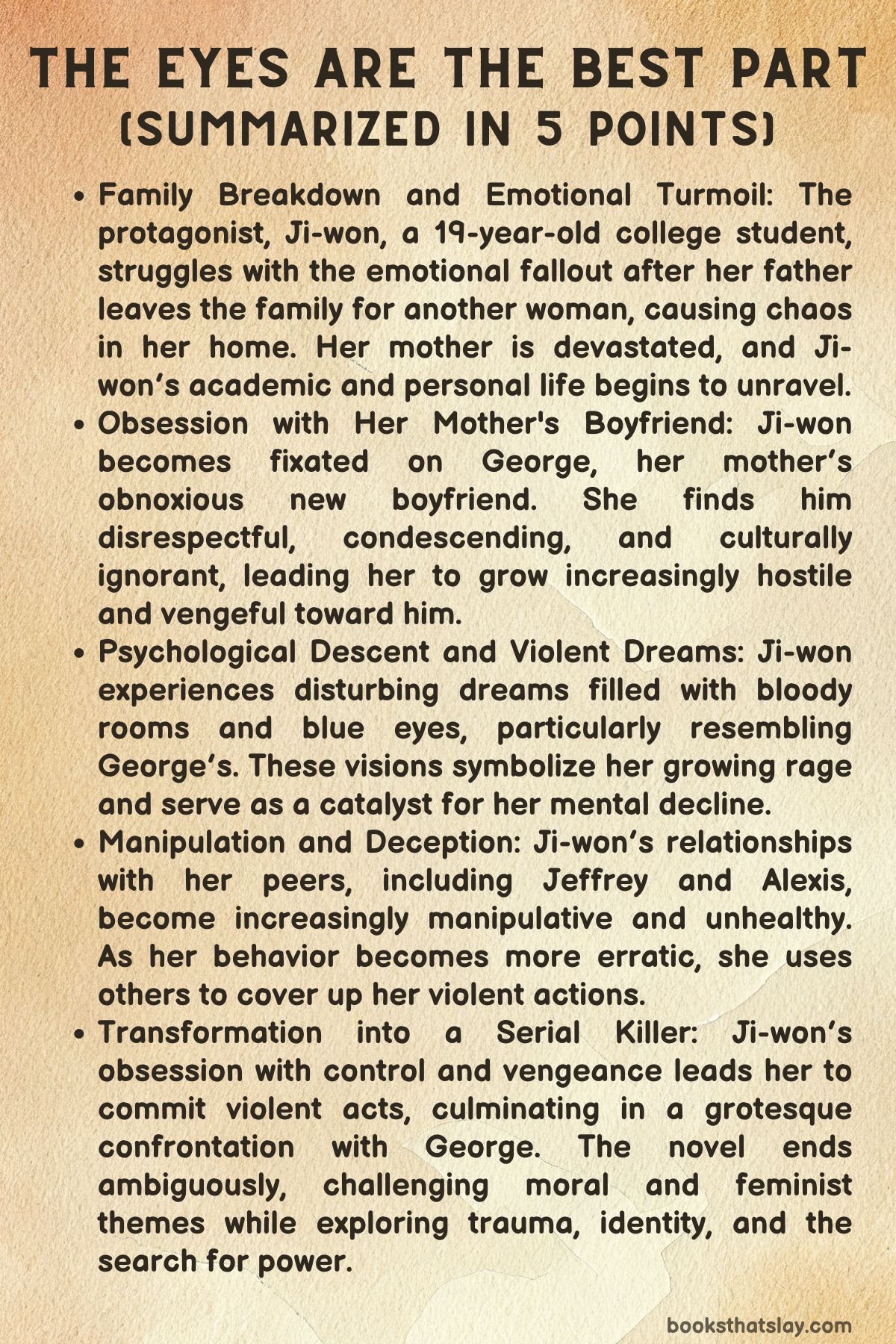

The Eyes Are the Best Part by Monika Kim is a gripping and disturbing psychological horror novel that delves deep into the mind of Ji-won, a young Korean-American woman whose life begins to unravel after her father leaves her mother for another woman.

As she grapples with the emotional chaos that follows, Ji-won’s obsession with her mother’s new boyfriend, George, intensifies, spiraling into a disturbing series of violent acts. Blending dark humor, body horror, and themes of identity, family dysfunction, and societal expectations, the novel explores Ji-won’s descent into madness with a chilling and unsettling narrative.

Summary

The Eyes Are the Best Part follows Ji-won, a 19-year-old college freshman whose life is thrown into turmoil after her father, Opa, leaves the family for another woman. This betrayal devastates her family, leaving her mother, Umma, emotionally shattered and unable to accept the reality of the situation.

Ji-won’s younger sister is confused and hurt by the sudden departure, and Ji-won herself struggles with her declining academic performance and increasing emotional instability. She feels isolated, unable to cope with the chaos her family is experiencing.

As Ji-won tries to hold her life together, her mental state begins to deteriorate.

She starts having disturbing dreams where she walks through bloody rooms filled with eyes—succulent blue eyes that remind her of George, Umma’s new boyfriend. George is a pompous, condescending man who has moved in with her mother after Opa’s departure.

His cultural ignorance and disrespectful attitude toward Ji-won and her sister, paired with his unsettling behavior, make Ji-won’s hatred for him grow. George, who flaunts his inflated sense of self-worth, particularly enjoys belittling Ji-won’s family, and Ji-won is driven to the brink by his presence.

At college, Ji-won’s relationships with her peers are equally fraught. She befriends Jeffrey and Alexis, two students who initially seem harmless but gradually reveal darker sides.

Jeffrey, who at first appears to be a supportive friend, turns out to be obsessive and manipulative, while Alexis, a fellow student, engages in flirtations that slowly expose her own self-serving motives.

Ji-won’s strained relationships with these individuals deepen her sense of alienation and dissatisfaction.

As Ji-won’s anger festers, her dreams become more violent, and she begins to rationalize her growing resentment towards George.

His eyes—those strikingly blue eyes—become a symbol of everything that is wrong with her life. She starts to believe that George’s presence is the cause of her family’s disintegration and vows to do something about it.

Her descent into madness accelerates as she manipulates those around her, including Jeffrey and Alexis, in her attempt to cover her tracks and conceal her increasingly erratic behavior.

The novel becomes a tense exploration of Ji-won’s psychological unraveling. She tries to hide the truth from herself and others, but her violent actions leave a trail of victims.

Among them is a homeless man who becomes an early casualty of Ji-won’s growing obsession with power and control.

Her actions culminate in a shocking and grotesque confrontation with George, where the lines between fantasy and reality blur, leaving readers to question the true extent of Ji-won’s descent.

The novel ends with an ambiguous conclusion, offering no clear answers or moral judgments about Ji-won’s actions.

The feminist undercurrent of the story challenges conventional notions of morality, particularly through Ji-won’s violent, albeit deeply flawed, pursuit of agency in a world that has continually marginalized her.

As a psychological horror, The Eyes Are the Best Part provides a complex portrait of trauma, grief, and rage, set against the backdrop of cultural and familial expectations.

Through Ji-won’s transformation into a serial killer, the novel paints a haunting, ambiguous picture of a woman’s struggle to reclaim power in a world that has taken everything from her.

Characters

Ji-won (Jan)

Ji-won is the central character of The Eyes Are the Best Part and the narrative primarily explores her mental and emotional unraveling. At the start of the novel, Ji-won is a 19-year-old college student who is grappling with a series of personal tragedies, most notably the collapse of her family due to her father’s extramarital affair.

The emotional betrayal of her father leaving the family creates an unstable foundation that only deepens her psychological turmoil. Ji-won is initially depicted as a young woman who is struggling with failure at school, the emotional disarray within her family, and the growing tension between her and her mother.

However, her character evolves significantly throughout the novel. She becomes increasingly consumed by rage, particularly toward her mother’s new boyfriend, George, whose presence in the household exacerbates her sense of betrayal.

Her obsession with George’s blue eyes symbolizes her descent into madness, and her growing fantasies about violence reflect her internal conflict. Ji-won’s transformation from a victim of her circumstances to a perpetrator of violence highlights the psychological horror at the heart of the novel, exploring themes of revenge, identity, and the impact of familial trauma.

Umma (Ji-won’s Mother)

Umma, Ji-won’s mother, plays a pivotal role in shaping the family’s dynamic after her husband’s departure. Stricken with grief and denial, Umma is unable to accept that her husband will not return, clinging to false hope despite the overwhelming signs that their marriage is over.

Her emotional vulnerability renders her an easy target for manipulation, and when she meets George, she turns to him as a means of emotional solace. George’s condescending attitude toward her daughters and his inappropriate behavior create a rift between him and the family, but Umma remains largely oblivious to his shortcomings, believing his presence will heal her pain.

Her inability to confront the disintegration of her family contributes to Ji-won’s alienation and resentment toward her. While Umma’s portrayal is sympathetic at times, her refusal to acknowledge the reality of her situation serves to deepen the emotional distance between her and her daughters, especially Ji-won, who feels increasingly neglected and unimportant.

George (Umma’s Boyfriend)

George is a key antagonist in the novel, representing everything Ji-won loathes about her family’s disintegration and the emotional harm inflicted upon her. His presence in the household after her father’s departure becomes a source of tension, particularly as he embodies a patronizing and culturally insensitive attitude toward Ji-won and her sister.

George’s background as a military consultant in South Korea gives him a false sense of cultural awareness, which only fuels his arrogance. He constantly undermines Ji-won’s identity, making her feel inferior and disregarded.

His fetishistic obsession with Asian women makes him a symbol of the racial and cultural challenges Ji-won faces as a Korean-American woman. Despite his inflated self-image, George is depicted as obnoxious and dismissive, which exacerbates Ji-won’s growing resentment and feelings of powerlessness.

His ultimate role in the narrative serves as the catalyst for Ji-won’s violent actions, as she begins to perceive him as the embodiment of everything wrong in her life. The novel’s portrayal of George critiques his position of privilege and his inability to understand the emotional and cultural intricacies of Ji-won’s world.

Jeffrey

Jeffrey is one of Ji-won’s college peers, initially introduced as a potential ally and friend. However, as the novel progresses, Jeffrey’s character reveals itself to be more sinister and manipulative.

Though his actions are not as overtly destructive as George’s, Jeffrey’s obsession with Ji-won and his ability to charm her under the guise of kindness showcase his more toxic traits. His initial behavior appears to be supportive, but he becomes increasingly controlling, particularly in his interactions with Ji-won.

He represents the type of man who masks his entitlement with a façade of benevolence, making his obsessive and intrusive nature all the more dangerous. Jeffrey’s behavior complicates Ji-won’s emotional landscape, particularly as she begins to confront her own identity and desires.

His transition from a seemingly good guy to a more unsettling figure underlines the novel’s exploration of manipulation and unhealthy power dynamics in relationships. His inability to accept Ji-won’s autonomy leads to his eventual downfall, mirroring the themes of control and repression that run throughout the story.

Alexis

Alexis is another college acquaintance of Ji-won’s, and her role in the narrative is more complex and layered. Initially, she seems to offer Ji-won a form of companionship and understanding, particularly when their relationship takes on a flirtatious nature.

However, as their bond deepens, Alexis’s self-interested motives begin to surface. She uses Ji-won’s emotional vulnerability for her own gain, demonstrating a lack of genuine empathy for Ji-won’s struggles.

Alexis embodies the idea of complicity in toxic relationships, as she manipulates Ji-won while presenting herself as a supportive figure. Her interactions with Ji-won ultimately underscore the novel’s theme of power imbalance in relationships, particularly the ways in which people can exploit others’ weaknesses.

Alexis’s flirtations, which initially appear harmless, reflect the theme of emotional manipulation and the difficulty of navigating genuine connections when trust is fractured. Alexis’s complexity as a character adds to the narrative’s exploration of the dangers of false intimacy and the human tendency to use others to fulfill personal desires.

The Homeless Man

The homeless man Ji-won encounters early in the novel represents one of her first victims and serves as a harrowing reflection of the internal violence she begins to unleash. His death marks a critical point in her psychological breakdown, as it reveals her ability to dehumanize others in her pursuit of control and revenge.

The act of violence against the homeless man symbolizes Ji-won’s descent into madness, as her desire for retribution begins to extend beyond George and her immediate family. His tragic fate is a stark reminder of the consequences of Ji-won’s unchecked rage, and it serves as a chilling foreshadowing of the horrors she will continue to commit.

The homeless man’s death also highlights the novel’s larger themes of alienation and powerlessness, as Ji-won seeks to assert control over her world in increasingly grotesque and destructive ways. His character is pivotal in setting the tone for the novel’s exploration of violence, identity, and the haunting consequences of trauma.

Themes

The Psychological Toll of Familial Betrayal and Dysfunction on Identity Formation

At the core of The Eyes Are the Best Part lies a psychological exploration of how familial betrayal and dysfunction can shape a young person’s identity and perception of the world. Ji-won’s life is irrevocably altered when her father’s infidelity leads to his abandonment of the family.

Her mother’s inability to accept this betrayal and her resulting emotional collapse contribute to the fractured dynamic at home. As Ji-won struggles to reconcile the idealized version of her family with the painful reality of her father’s departure, her sense of self becomes increasingly unstable.

The emotional turmoil experienced by Ji-won, from feeling abandoned by her father to being subjected to her mother’s emotional disarray, sets the stage for her descent into violence and psychological decay. Her family’s disintegration becomes the backdrop for her unraveling mental state, where feelings of neglect and resentment turn into deep-rooted anger and ultimately, a distorted sense of agency.

Her transformation into a violent, manipulative figure is driven not only by the betrayal of her father but also by the failure of her family to offer support or a stable emotional foundation.

The Intricacies of Cultural Alienation and Its Impact on Gendered Expectations

The novel intricately portrays Ji-won’s alienation, not only within her family but also in relation to the broader society, which subtly or overtly enforces gendered expectations. Ji-won’s struggles with her identity as a Korean-American woman are amplified by the pervasive cultural expectations placed upon her, both by her family and society at large.

Her mother’s adherence to traditional Korean values, combined with her emotional dependence on a new boyfriend who disrespects Ji-won’s cultural heritage, forces Ji-won to confront her position within this dynamic. George, her mother’s boyfriend, symbolizes the exoticizing and fetishizing attitude that she must navigate.

His patronizing behavior, rooted in his self-appointed “cultural awareness,” underscores the subtle racism Ji-won faces—being simultaneously objectified and dismissed. The novel highlights the tension between Ji-won’s Korean heritage and the societal pressures that expect her to conform to both Western ideals and traditional gender roles, leaving her caught in an emotional and cultural limbo.

This tension becomes a critical aspect of her psyche, exacerbating her feelings of powerlessness and rage, which later manifests as violence.

The Feminist Examination of Agency, Autonomy, and Violence in a Patriarchal Context

At its core, The Eyes Are the Best Part is a feminist dissection of agency and autonomy within a patriarchal framework, where a young woman’s rebellion against systemic oppression takes the form of violence. Ji-won’s journey is one of self-empowerment, but it is a deeply troubling and morally ambiguous path.

The patriarchal structures that govern her life—from her father’s abandonment and her mother’s emotional dependence on George to the subtle misogyny she encounters at college—force her to confront the limitations placed on her autonomy. While society expects her to be passive, quiet, and obedient, her violent acts become a perverse assertion of her power.

Ji-won’s violent transformation is not simply a reaction to external abuse, but a reclamation of control in a world where her autonomy is continually undermined. However, the novel complicates the notion of empowerment, blurring the lines between justice and retribution, as Ji-won’s acts of violence—though understandable within the context of her emotional and cultural disintegration—are depicted in morally ambiguous terms.

This unsettling portrayal forces readers to question the true nature of empowerment and whether violence can ever be justified as a means of reclaiming agency.

The Pathological Consequences of Fetishization and Objectification on Mental Health

One of the novel’s most disturbing and poignant themes is the examination of fetishization and objectification, particularly the destructive impact they have on the mental health of marginalized individuals. Ji-won’s growing obsession with George’s blue eyes—and later with the act of consuming eyes themselves—serves as a grotesque metaphor for how she internalizes the objectification she faces as an Asian woman.

George’s condescending and racially charged behavior toward Ji-won, combined with his objectification of her and other women, further pushes her toward an emotional breakdown. The fetishization she experiences from men—whether it’s George’s blatant fetish for Asian women or Jeffrey’s obsessive pursuit—feeds into Ji-won’s deteriorating mental health.

The novel links this external dehumanization with her own distorted sense of self-worth and a breakdown of personal boundaries. Her increasing fixation on eyes, which symbolically represent both the gaze of objectification and the idea of “seeing” and “being seen,” illustrates how deeply ingrained fetishization can warp a person’s sense of reality.

The Intersection of Grief, Trauma, and the Loss of Innocence in the Face of Family Collapse

Grief and trauma permeate every aspect of Ji-won’s life, particularly in how these emotional experiences intertwine with the loss of innocence and the transformation of her psyche. The abandonment of her father sets in motion a series of events that expose Ji-won to the harsh realities of life and forces her to confront the emotional scars of her childhood.

The failure of her family to offer her the support she needs during this vulnerable time exacerbates her sense of isolation and internalized rage. This emotional abandonment, compounded by her mother’s reliance on an unsuitable new partner, forces Ji-won into a position where she must fend for herself.

The gradual loss of innocence is palpable as she moves from being a victim of her circumstances to an active participant in her own destruction. The trauma she experiences is not just emotional but deeply rooted in the realization that she is powerless to alter the course of her family’s fate.

This understanding fuels her descent into a darker, more nihilistic worldview, where violence and control become her only means of navigating a world that has rejected her and, in turn, helped shape her into a serial killer.

The Ambiguity of Morality and Justice in the Context of Personal Retribution and Societal Expectations

The novel’s exploration of Ji-won’s actions is deeply ambiguous, asking readers to wrestle with the morality of her choices within a context of deep emotional and familial turmoil. As Ji-won becomes increasingly consumed by her rage, her violent actions against George and others take on a dual role—both as personal retribution and as an attempt to correct the perceived injustices of her life.

The line between victim and perpetrator blurs, as the novel does not offer a clear moral judgment on Ji-won’s descent into violence. Instead, it forces readers to question the very nature of justice and retribution in a society that has allowed her to be both a victim of systemic oppression and a product of familial collapse.

Ji-won’s acts of violence seem to exist in a space outside traditional notions of good and evil, pushing readers to grapple with the complexities of her character. The lack of a clear resolution or moral condemnation at the novel’s end underscores the tension between societal expectations and individual desires for justice, leaving readers with an unsettling sense of unresolved conflict.