The Last One at the Wedding Summary, Characters and Themes

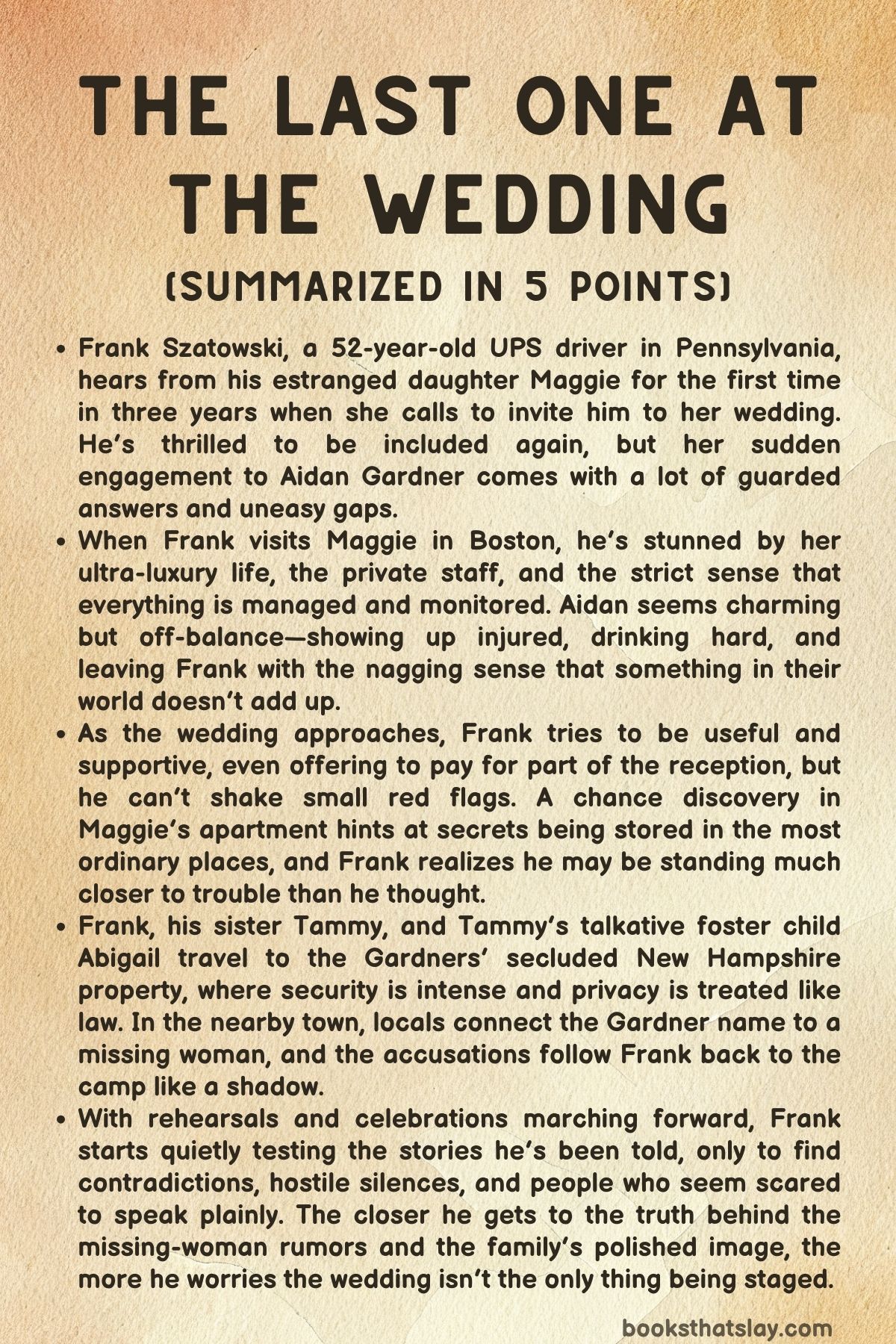

The Last One at the Wedding by Jason Rekulak is a tense, fast-moving story about a father who gets one unexpected second chance—and realizes it may come with a price. Frank Szatowski is a working-class UPS driver who has spent years trying (and failing) to reconnect with his daughter, Maggie.

When she suddenly invites him to her wedding, Frank wants to believe it’s a fresh start. But the closer he gets to Maggie’s new life—wealthy, secretive, and guarded by powerful people—the more he suspects the celebration is covering up something dangerous.

Summary

Frank Szatowski, a 52-year-old UPS driver in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, is eating breakfast when his phone rings from an unknown number. It’s Maggie—his daughter, who hasn’t spoken to him in three years.

The first call drops, but when she calls back, she’s clear: she’s fine, living in Boston, and she’s getting married. Maggie invites Frank to the wedding on July 23 in New Hampshire.

Frank, shaken with relief and hope, agrees immediately.

Maggie tells him her fiancé is Aidan Gardner, a 26-year-old painter who also teaches art. Frank tries to ask about Aidan’s family, but Maggie dodges, saying it’s complicated and they’ll talk when Frank meets them in Boston.

Instead of dinner out, Maggie has Frank come to their apartment. Frank drives up, brings gifts, and arrives at a building so upscale it throws him off.

Staff already know his name, check his ID, and send him up in a strange elevator that opens straight into Maggie and Aidan’s huge apartment—filled with Aidan’s stark portrait paintings and staffed by Lucia, their private chef.

Maggie looks polished and confident in a way Frank barely recognizes. On the balcony, she finally explains why Aidan’s family is “complicated”: Aidan’s father is Errol Gardner, the CEO of Capaciti and the man behind the Miracle Battery.

Frank’s mind races as he tries to place his daughter’s life inside a world this wealthy and controlled. When Aidan arrives, he’s bruised and cut up, claiming he was attacked after an art event in Chicago.

He refuses to report it and keeps drinking through dinner, while Maggie talks excitedly about the wedding and her massive heirloom engagement ring.

Before the night ends, Maggie shares more news: she’s being promoted at Capaciti to a new aerospace-focused division tied to electric air travel. Frank is proud and stunned at how far she’s gone.

In the bathroom, he fixes a running toilet and notices something odd—an object in a black plastic bag duct-taped under the tank lid. He doesn’t investigate in time and leaves it behind, uneasy.

Back home, a formal invitation arrives. Frank’s sister Tammy is thrilled and starts digging into the Gardner family.

Frank insists on contributing to the wedding and offers to pay for the alcohol. Maggie resists, but Errol calls Frank and smoothly agrees to accept an $8,000 payment toward the bar.

Frank spends the following weeks preparing, renting a tux, struggling to write a toast, and trying to connect with Aidan—who stays distant and unreliable. Maggie is busy and hard to reach, telling Frank they’ll have time together once he arrives at the Gardner family camp, Osprey Cove, a couple of days before the ceremony.

Then a typed-address envelope arrives from Hopps Ferry, New Hampshire. Inside is a printed photo of Aidan with a smiling young woman by a lake.

Scrawled across it: “WHERE IS DAWN TAGGART???” Frank calls Maggie in alarm. She says Dawn Taggart is a local woman who vanished months earlier and claims Dawn’s mother is harassing the Gardners for money.

Maggie tells Frank to seal the items in a bag and bring them to New Hampshire for the family’s lawyers.

Frank wakes early on departure day, haunted by memories of raising Maggie after her mother Colleen died—his mistakes, their fights, and the moment everything broke. He picks up Tammy, only to learn she’s bringing her foster child, ten-year-old Abigail Grimm, because another placement fell through.

Frank protests, but Tammy refuses to leave Abigail behind. On the drive north, Frank’s anxiety grows—not only about facing the Gardners, but about how out of place he feels.

They stop in Hopps Ferry, where Frank sees missing-person flyers for Dawn Taggart. A local man, Brody Taggart, confronts them and explodes when he recognizes the Gardner name, accusing Aidan of getting Dawn pregnant, killing her, and hiding her body at Osprey Cove.

Others dismiss him as unstable, but the accusation sticks in Frank’s mind.

Osprey Cove turns out to be heavily secured: gates, guards, a manager named Hugo who knows everyone’s movements, and a thick “privacy document” Frank is pressured to sign. Maggie and Aidan greet them warmly, and Abigail is quickly recruited to replace a sick flower girl.

Frank is given a luxurious lakeside cottage, but Maggie stays busy with wedding crises and disappears into her schedule.

Frank wanders and sees Aidan slip into the woods with a red-haired woman. Curiosity and worry push Frank to follow.

He finds a hidden studio filled with unsettling portraits and even a staircase leading to a shelter below. The woman is Gwendolyn, Aidan’s art-school friend, who argues with him about “telling the truth” and threatens to speak to someone named Margaret.

Aidan tries to downplay it, but the tension feels real. Soon after, Gwendolyn turns up dead, labeled an overdose, and the camp quickly moves on as if nothing happened.

Frank can’t let it go. He sneaks into town and tracks down Brody and Dawn’s mother, Linda Taggart.

Linda tells Frank Dawn had a secret relationship with Aidan: gifts, secrecy, control, and distance as the months passed. On November 3, Dawn left home upset, her phone tracking toward Osprey Cove before the signal vanished.

Linda says the evidence disappeared from police records and believes the Gardners paid to bury the truth. Frank returns to camp shaken—until Maggie shows him a detail on the photo that suggests it was edited, undermining Linda’s key proof and making Frank doubt himself.

Still, Frank keeps watching. At the rehearsal events, Aidan looks sick and distracted.

Frank steals Aidan’s phone and uses it to access Catherine Gardner’s room, suspecting the family is hiding more than they admit. Inside, he finds Catherine in squalor, intoxicated and neglected.

In fragments, she reveals the real story: Errol had an affair with Dawn. When Dawn demanded money after announcing she was pregnant, Catherine struck her with a battery pack; Dawn fell down the stairs and died.

Aidan helped cover it up. Before Frank can get more, Hugo and others rush in, sedate Catherine, and warn Frank to stop asking questions.

Aidan privately confirms his mother’s account and implies Hugo is dangerous.

Frank goes looking for Maggie, desperate to confront her and pull her away. Instead, he finds her in bed with Errol Gardner.

Rage takes over. Frank attacks Errol, but Hugo knocks Frank out.

Frank wakes bruised, and Tammy insists he must have fallen while drunk. When Frank tells her what he saw and what Catherine admitted, Tammy refuses to act, clinging to the security and wealth now offered to her.

The true threat becomes clear when Frank later visits Maggie and is pulled into a conversation with Errol and the family’s lawyer, Gerry. They ask where Abigail is staying.

Frank realizes they see the child as a loose end because Abigail found a camp map marked with an X and has heard the rumors about Dawn. Their solution is chilling: remove the risk by making Abigail disappear.

Frank pretends to accept it and bargains for stock to sell his silence, buying time.

In the bathroom, Frank calls Tammy and orders her to flee with Abigail immediately and tell no one where they’ve gone. Then he retrieves the black pouch hidden under the toilet tank: a data device containing Maggie’s secret recordings of conversations with Errol, Aidan, Gerry, and others—evidence of schemes, manipulation, and the wedding’s ugly foundation.

When Maggie realizes the device is missing, Hugo corners Frank with a gun, but chaos breaks out and Frank fights his way free, sets off fire alarms, and escapes into the street crowd.

Frank races home and turns to Vicky, a salon owner who has been a quiet support in his life. Together they listen to the recordings and confirm what Frank feared: deals, coercion, and an arrangement that makes the marriage look less like love and more like a transaction.

Months later, Abigail performs in a school musical. Tammy has adopted her, and Frank is part of her daily life.

Frank tries to see Maggie in prison, but she refuses to meet him. The fallout continues: Dawn’s body is recovered, Hugo is arrested and extradited, and the Gardners face charges while fighting for control of the narrative.

Frank leaves with the one thing he came for in the first place—someone to protect, and a chance to do right by her.

Characters

Frank Szatowski

In The Last One at the Wedding, Frank is the emotional and moral center of the story: a 52-year-old UPS driver whose ordinary life and plainspoken decency collide with a world of extreme wealth, power, and calculated cruelty. His estrangement from Maggie defines his deepest wound, so her call immediately pulls him into a role he both craves and fears—father again, but on unfamiliar ground where every gesture is scrutinized and every assumption can be weaponized.

Frank’s defining trait is persistence rooted in love: he keeps showing up even when he is outclassed socially, confused by the Gardners’ systems, and repeatedly warned to stop asking questions. That stubbornness is not mere pride; it is a working-class ethic turned parental instinct, and it becomes his form of courage.

His arc moves from wanting reconciliation at any cost to realizing that real fatherhood may require confrontation, refusal, and sacrifice, especially once he understands Maggie is not simply a victim of the Gardners but also a participant in their moral rot. Frank’s investigative drive is fueled by guilt, grief, and a need to make sense of what he failed to protect in the past—his late wife’s memory, Maggie’s childhood stability, and now Abigail’s safety.

By the end, he becomes a “hero” not through status or strength, but by choosing protective action over comfort, and truth over the illusion of family unity.

Maggie Szatowski

Maggie is the most psychologically charged character in The Last One at the Wedding because she embodies both the longing for a healed family and the terror of what ambition can do to empathy. When she reconnects with Frank, she appears polished, successful, and emotionally controlled, setting firm boundaries about the past as if vulnerability is a liability.

That posture reads at first like self-preservation, but it gradually reveals a deeper pattern: Maggie curates reality the way the Gardners do, by selecting what others are allowed to know and reframing threats as inconveniences. Her job at Capaciti and sudden promotion place her at the intersection of corporate power and personal reinvention, and she uses that position to rewrite herself into someone who can survive among the ultra-wealthy.

Crucially, Maggie’s relationship with Aidan and the Gardners functions less like romance and more like a negotiated arrangement, where affection is secondary to strategy and containment. The discovery of her recordings shows her as both meticulous and distrustful—someone gathering leverage, perhaps from fear, perhaps from calculation, perhaps from both.

Maggie’s most disturbing dimension is her willingness to rationalize harm, especially when Abigail becomes a “risk” to be managed; she speaks in the cold language of inevitability, as though morality is a luxury other people can afford. Her tragedy is that she resembles Frank in grit and intelligence, but she has redirected those traits away from care and toward control, turning survival into complicity.

Aidan Gardner

Aidan is constructed as an enigma in The Last One at the Wedding, a man whose apparent fragility and artistic sensitivity mask a history of secrecy, manipulation, and moral surrender. He presents himself as a painter-teacher with a bruised face and a story that does not quite fit, immediately placing doubt around his credibility and inviting the reader to see him as both victim and suspect.

His art, especially the unsettling portraits and the hidden studio, mirrors his inner life: curated surfaces with something claustrophobic underneath, like a mind that cannot fully exit the family bunker he was raised in. With Dawn Taggart, Aidan’s pattern reads as predatory in its softness—lavish gifts, isolation, and compartmentalization—less overt violence than a steady reshaping of another person’s options until they depend on him.

Yet Aidan is not portrayed as a confident mastermind; he often seems sick, distracted, and cornered, suggesting a man who has learned to comply to survive within Errol and Catherine’s orbit. His complicity in hiding Dawn’s body marks the point where he becomes morally indistinguishable from the family machine, regardless of what he may feel privately.

The staged nature of his marriage to Maggie makes him a symbol of transactional intimacy: a person turned into a role, performing devotion under coercion and privilege at the same time. Aidan’s fear of Hugo and his warnings to Frank underline that he is both perpetrator and prisoner, a product of a system that weaponizes loyalty.

Errol Gardner

Errol is the novel’s embodiment of corporate charisma fused with predation: a CEO who speaks smoothly, negotiates easily, and treats human lives as variables. In The Last One at the Wedding, he appears first as a distant titan—wealthy, praised, and seemingly gracious—yet every later reveal reframes that charm as a tool for control.

His “fatherly” compliments toward Maggie and joking rapport with Frank function like soft bribes, inviting people to feel chosen and safe while he evaluates what they can be used for. The affair with Dawn and the attempt to buy silence expose his core belief that consequences are negotiable and truth is malleable.

Errol’s most chilling feature is how quickly he shifts into logistics when discussing harm, especially in the plan to eliminate Abigail; he treats murder like risk management with an attached philanthropic press release. Even his generosity, like gifting Tammy stock, is transactional, designed to create loyalty and dependency.

Errol represents a particular kind of power that does not need to shout: it smiles, funds scholarships, and moves bodies in the background.

Tammy Szatowski

Tammy functions as Frank’s closest mirror and his most painful disappointment in The Last One at the Wedding. As a sister and foster parent, she initially reads as energetic, practical, and devoted, someone who moves through life with busy competence and an instinct to “keep things going.” Her decision to bring Abigail, her insistence on etiquette, and her excitement about the wedding reveal both her desire to belong and her anxiety about being judged.

Tammy’s arc is a study in how ordinary people can be captured by extraordinary wealth: the moment Errol gifts her Capaciti stock, her skepticism collapses into gratitude, and gratitude becomes moral surrender. She rationalizes, minimizes, and rewrites events so she can stay in the warm glow of new security, even when Frank’s warnings become too specific to ignore.

Tammy is not evil; she is seduced. Her tragedy is that she treats comfort as proof of goodness, mistaking gifts for character, and in doing so she abandons the very protective instincts her fostering role should sharpen.

Yet by the end, her adoption of Abigail suggests a delayed reclamation of conscience, as if the reality Frank forced her to face eventually outweighs the fantasy she wanted.

Abigail Grimm

Abigail is both innocence and evidence in The Last One at the Wedding, a child whose presence turns the adult world’s corruption into something undeniable. Her chatter, jokes, and obsessive etiquette studying make her seem quirky and comedic at first, but those traits also read as survival strategies: she performs cheerfulness and “properness” to secure safety in unpredictable homes.

Her fear of sleeping outside, her panic at the spiders, and her overeating-vomiting episode show a nervous system shaped by instability and neglect, not simply childish fussiness. Because she is observant and talkative, Abigail becomes dangerous to the Gardners—not through malice, but through memory.

The “map with an X” positions her as an accidental witness, and the adults’ willingness to consider killing her reveals the story’s starkest moral line. Abigail’s later “heroes” essay about Frank reframes the entire narrative: she becomes the measure of what Frank’s love actually accomplished, turning his messy, frightened bravery into something a child can recognize as care.

Colleen Szatowski

Colleen, though absent in the present action, is a quiet gravitational force in The Last One at the Wedding. As Frank’s late wife and Maggie’s mother, she represents a past version of family life that still shapes Frank’s conscience and grief.

Frank’s memories of her tipping generously, and his attempt to repeat that small ritual, show how he clings to her values as a compass when everything around him feels distorted. Colleen’s presence is also a reminder that Frank’s parenting happened under pressure and loss; he is not simply a man who made mistakes, but a man who tried to hold a household together after death.

The suitcase that once belonged to Colleen, now carried by Abigail, becomes an understated symbol of how trauma and caretaking pass from one vulnerable person to another, binding Frank’s old family to his new responsibility.

Lucia

Lucia is introduced as a private chef, but in The Last One at the Wedding she also becomes an accidental truth-teller through reaction rather than speech. Her role highlights the Gardners’ curated luxury—multi-course vegan meals, impeccable service, controlled environments—while her human alarm punctures that façade when she witnesses Hugo’s gun.

Lucia’s scream and the crashing platter are not just a plot disruption; they are a moral interruption, the moment when the polished world cannot keep pretending it is civilized. She represents the working people inside elite spaces who see more than they are supposed to, yet are expected to remain invisible.

Hugo

Hugo is the novel’s physical threat and its clearest portrait of outsourced violence. In The Last One at the Wedding, he appears courteous, efficient, and relentlessly “helpful,” using friendliness as surveillance and procedure as intimidation, from the privacy document to the constant monitoring at Osprey Cove.

His “Gardner Standard Time” detail reveals how control extends even to clocks, and Hugo is the enforcer of that reality. The hints about his past violence and the ease with which he escalates to a pistol show him as a man trained to treat coercion as routine.

Hugo is terrifying not because he is unpredictable, but because he is predictably loyal to power; he does not need personal hatred to harm someone. His eventual arrest and extradition underline that he is both agent and disposable asset—useful until he becomes a liability.

Dawn Taggart

Dawn is the story’s central absence: a missing woman whose disappearance exposes the machinery beneath the wedding’s glitter. In The Last One at the Wedding, Dawn’s relationship with Aidan is framed through class imbalance and secrecy, with gifts standing in for legitimacy and silence replacing community.

Her pregnancy becomes the trigger that converts private exploitation into public danger, because it threatens to create an undeniable tie that money cannot fully erase. Dawn’s fate is also a commentary on who is considered “missable”: her family’s claims are treated as nuisance, their evidence is dismissed or erased, and their grief is positioned as inconvenience to the powerful.

The recovery of her body at the end restores a measure of truth, but it cannot restore what was taken; Dawn’s narrative function is to show that the Gardners’ wealth does not simply buy comfort, it buys the ability to rewrite reality until someone like Dawn nearly vanishes from it.

Linda Taggart

Linda is grief sharpened into clarity. In The Last One at the Wedding, she counters the narrative Maggie offers by presenting a sober, detailed account that refuses to be smoothed into “harassment.” Her hospitality toward Frank, even while holding rage, shows a person trying to remain human in a situation designed to dehumanize her.

Linda’s story about Dawn is persuasive because it includes emotional complexity: shame, secrecy, hope, and then dread. Even when the photo evidence is revealed as manipulated, Linda’s larger point remains intact—that the powerful can bend institutions and public perception—making her both potentially misled and still fundamentally right about the system.

She embodies the frustration of people who know the truth of what happened but cannot make it stick in a world where power edits facts.

Brody Taggart

Brody is volatility born from helplessness. In The Last One at the Wedding, he is dismissed as the “village idiot,” but his fury functions like an alarm the community does not want to hear.

His accusations are messy and extreme, yet they emerge from the same core insight Linda shares: money changes what can be made to disappear. The AR-15 confrontation shows how fear and rage have turned him into someone who expects violence everywhere, including from strangers.

Brody represents the destructive side of grief when institutions fail—what happens when justice feels so unreachable that paranoia becomes self-defense.

Gwendolyn

Gwendolyn is a disruptive witness in The Last One at the Wedding, someone close enough to Aidan to know his fractures and bold enough to threaten exposure. Her sharpness toward Frank and her contempt for the wealth around her suggest she refuses the social scripts Osprey Cove demands, which makes her inherently dangerous to the Gardners’ controlled narrative.

Her death, framed as an overdose with tranquilizers, reads as both a warning and a test: it teaches Frank how quickly inconvenient people can be erased and then packaged as tragedy. Gwendolyn’s narrative purpose is to show that proximity to truth is hazardous, and that art-world intimacy with Aidan does not protect anyone from the Gardner apparatus.

Catherine Gardner

Catherine is the grotesque underside of the Gardner family image: the matriarch revealed in squalor, intoxication, and neglected decay. In The Last One at the Wedding, her condition suggests not only addiction but containment, as if the family keeps her hidden because she is both embarrassing and dangerous.

Her confession about killing Dawn during a confrontation collapses the mystery into something brutally mundane: not a cinematic conspiracy, but a moment of violent entitlement followed by efficient cover-up. Catherine is also the character through whom the story hints at deeper rot, especially when she implicates “Margaret,” suggesting layers of complicity even she cannot fully articulate cleanly.

She represents how wealth can preserve people from accountability while simultaneously destroying them internally, leaving a hollowed figure whose truth leaks out only when the mask slips.

Gerry

Gerry, Errol’s attorney, personifies institutional evil: not the one who swings the weapon, but the one who makes the weapon “reasonable.” In The Last One at the Wedding, he frames the plan to kill Abigail as a forward-looking problem-solving exercise, wrapping violence in professional language and charitable branding. His calmness is more horrifying than overt cruelty because it demonstrates how systems normalize atrocity.

Gerry’s negotiation with Frank over stock also reveals his belief that everyone has a price, a worldview that collapses morality into bargaining positions. He is a reminder that corruption is often paperwork with a smile.

Sierra

Sierra appears briefly, but her presence matters because she shows how fragile the Gardners’ control can be when confronted by ordinary observation. In The Last One at the Wedding, her grogginess and complaint about contacts feel mundane, and that mundanity becomes disruptive when she notices the dust and broken toilet—small details that pierce Frank’s attempted invisibility.

Sierra is not a hero, but she is a catalyst: the kind of person who, by speaking thoughtlessly, triggers consequences in a world where consequences are usually engineered. She represents how surveillance can come from anywhere in elite environments, not only from guards with guns.

Minh

Minh functions as a bridge to Maggie’s earlier self. In The Last One at the Wedding, her reminiscence about Maggie’s past and insistence that Maggie became stronger provides Frank with an outside narrative that is neither the Gardner PR story nor Frank’s guilt-soaked memory.

Minh’s role is to complicate the idea of Maggie as purely controlled by others; she suggests Maggie has always had a survival core, which can be admirable or frightening depending on what it serves. Minh represents the life Maggie might have had—peer relationships, shared history, grounded perspective—if she had not been absorbed into the Gardners’ reality.

RJ

RJ is a tonal mask: the jovial coworker-officiant who turns the rehearsal into a performance. In The Last One at the Wedding, his upbeat handling of the ceremony reflects how corporate culture can aestheticize sincerity, turning love into an event product.

He is not positioned as malicious, but as someone comfortable inside the Capaciti orbit, where everything is branded and smoothed. RJ’s function is to show how easily community becomes audience at Osprey Cove, and how celebration can be used to drown out doubt.

Vicky

Vicky represents grounded loyalty and practical decency, a counterweight to the Gardners’ world. In The Last One at the Wedding, she is someone Frank trusts enough to send his toast draft to, which signals that she knows him in his ordinary vulnerability.

When Frank returns desperate and uses her salon computer to open the recordings, Vicky becomes a witness who cannot be bought with stock or dazzled by status; her shock is the story’s sane reaction to what the powerful call “necessary.” Vicky’s presence also reinforces that Frank’s real support system is not wealth or prestige, but relationships built on everyday mutual regard.

Margaret

Margaret is an ominous reference rather than a fully seen character in the provided summary, which is precisely why the name carries weight. In The Last One at the Wedding, Catherine’s mention that “Margaret” was involved suggests a hidden layer of orchestration—someone whose influence is strong enough to be felt even through Catherine’s haze.

Whether Margaret is a family member, fixer, or corporate operator, the narrative function is clear: the conspiracy is not only personal, it is systemic, and there are always additional hands on the lever that the public never sees.

Themes

Estrangement and the Search for Reconciliation

The emotional center of The Last One at the Wedding lies in Frank Szatowski’s attempt to reconnect with his estranged daughter, Maggie, after years of silence. Their relationship, fractured by misunderstandings, pride, and unspoken resentment, becomes a study of how familial bonds can both endure and corrode under the pressure of time and guilt.

Frank’s yearning to repair what has been lost shapes every choice he makes, from his immediate acceptance of Maggie’s wedding invitation to his willingness to overlook the increasingly alarming events surrounding the Gardners. His journey is haunted by regret—by moments where he failed to show compassion or understanding—and this guilt renders him vulnerable to manipulation.

Yet his persistence in reaching out, even after discovering Maggie’s deception and complicity, underscores his need for emotional closure rather than forgiveness. Rekulak presents estrangement not merely as physical distance but as the emotional isolation created by secrets and moral compromise.

By the end, reconciliation transforms from a hopeful goal into an impossibility. The father-daughter dynamic becomes symbolic of a larger truth—that love cannot survive in an environment poisoned by ambition and deceit.

Frank’s eventual separation from Maggie, as she refuses to see him in prison, closes the narrative with tragic finality: reconciliation has been replaced by acceptance. Through their fractured bond, the novel explores the ache of parental love that persists despite betrayal and the quiet tragedy of realizing that some relationships can only be mended by walking away.

Power, Corruption, and Moral Decay

Throughout The Last One at the Wedding, power operates as both a corrupting force and a seductive promise. The Gardner family represents an elite class that manipulates truth, law, and human emotion to preserve control.

Errol Gardner’s empire, built on technological innovation, masks moral rot beneath its polished surface. The wealth that insulates the Gardners from consequence gradually ensnares Maggie, who evolves from an ambitious professional into a willing participant in deceit and exploitation.

Frank’s blue-collar honesty stands in stark contrast to their moral elasticity, and his gradual awakening to their corruption mirrors a broader critique of how unchecked privilege distorts justice and empathy. The novel’s chilling depiction of the family’s decision to eliminate a child for convenience demonstrates the complete erosion of conscience that accompanies absolute power.

Every character touched by the Gardners becomes morally compromised—Aidan through guilt and fear, Tammy through greed, and Maggie through ambition. Even Frank, initially the moral anchor, briefly contemplates silence in exchange for stock, revealing how easily ethics can falter when survival or belonging is at stake.

Rekulak crafts a portrait of power not as loud tyranny but as quiet manipulation—the ability to redefine truth, rewrite events, and erase human lives without consequence. The corruption extends beyond individuals to systems—police, media, and corporate institutions all serve the wealthy.

By the conclusion, power is shown not as strength but as decay: the more it is accumulated, the more humanity is lost.

The Illusion of Wealth and Success

Wealth in The Last One at the Wedding functions as both a mirror and a mask—reflecting characters’ desires while concealing their moral emptiness. Frank’s awe and discomfort upon entering Maggie’s luxurious apartment highlight the psychological distance between working-class authenticity and corporate privilege.

To him, the world of the Gardners is surreal, a place where every surface gleams yet nothing feels alive. This artificial perfection contrasts sharply with the emotional void that defines the characters who inhabit it.

Maggie’s transformation into someone sleek, ambitious, and detached from her roots demonstrates how success can isolate rather than fulfill. The Gardners’ world operates on appearance: curated dinners, grand estates, and lavish ceremonies hide the fractures beneath.

Aidan’s black eye, Catherine’s seclusion, and the secrecy surrounding Dawn Taggart’s disappearance all expose how wealth enables concealment. Rekulak uses the Gardners’ opulence to explore the moral vacuum that arises when image replaces substance.

For Frank, money initially symbolizes redemption—a way to prove worth to his daughter by paying for the wedding bar. But as he witnesses the manipulation and deceit that wealth sustains, it becomes a symbol of moral failure.

By the end, success stands revealed as a performance built on exploitation, and the glittering surfaces that once dazzled now serve as evidence of decay. The novel dismantles the myth that prosperity equates to virtue, showing instead that the pursuit of wealth often leads to spiritual impoverishment and ethical ruin.

Truth, Manipulation, and the Fragility of Perception

The novel constructs its tension through the distortion of truth. Every revelation Frank encounters is filtered through manipulation—half-truths, fabrications, and staged realities designed to control perception.

From Maggie’s evasive phone call to the doctored photograph of Aidan and Dawn, Rekulak shows how truth can be reshaped to protect those in power. The Gardners wield narrative control as a weapon, rewriting history to maintain their façade.

Even Maggie, once the victim of deception, becomes an architect of falsehoods, weaponizing charm and intellect to manipulate her father and others. This manipulation extends to institutions: police reports vanish, digital data is erased, and witnesses are silenced.

The fragility of perception becomes a recurring motif—what one sees or hears cannot be trusted. Frank’s gradual disillusionment forms the emotional core of this theme.

His journey from gullibility to clarity mirrors the reader’s, as both are drawn into a web of lies disguised as civility. When he finally obtains the hidden recordings, truth emerges not as liberation but as a burden, forcing him to confront the cost of knowing.

Rekulak uses this theme to comment on the modern condition of distorted realities, where technology and privilege allow truth to be edited and erased. In the end, truth survives only through human decency—Frank’s act of exposing the Gardners not for revenge but to protect a child affirms that integrity, though fragile, remains the final resistance against manipulation.

Redemption and the Persistence of Conscience

Frank’s evolution across The Last One at the Wedding is driven by the pursuit of redemption—both for his failures as a father and his earlier moral compromises. Haunted by moments of neglect, he seeks to reclaim his integrity through small acts of courage.

His decision to protect Abigail Grimm, even at personal risk, marks his moral awakening. The novel portrays redemption not as grand transformation but as a series of quiet, decisive choices that affirm humanity in the face of corruption.

Frank’s journey contrasts sharply with Maggie’s descent into moral blindness. Where she suppresses guilt to align with power, Frank confronts it and grows stronger.

His conscience, though battered by years of disappointment, becomes the anchor that guides him through deception. Redemption also carries a generational dimension: Frank’s bond with Abigail symbolically replaces the one he lost with Maggie.

Through caring for her, he restores the compassion and responsibility that once eluded him as a father. Rekulak suggests that redemption arises not from erasing the past but from accepting it and choosing differently in the present.

Frank’s final solitude—walking away from Maggie as alarms ring behind him—illustrates moral clarity achieved through loss. He cannot save his daughter, but he can save himself and an innocent child.

The novel closes on a somber but affirming note: conscience may not undo the damage of corruption, yet it remains the only force capable of preserving dignity when the world demands silence.