The Champagne Letters Summary, Characters and Themes

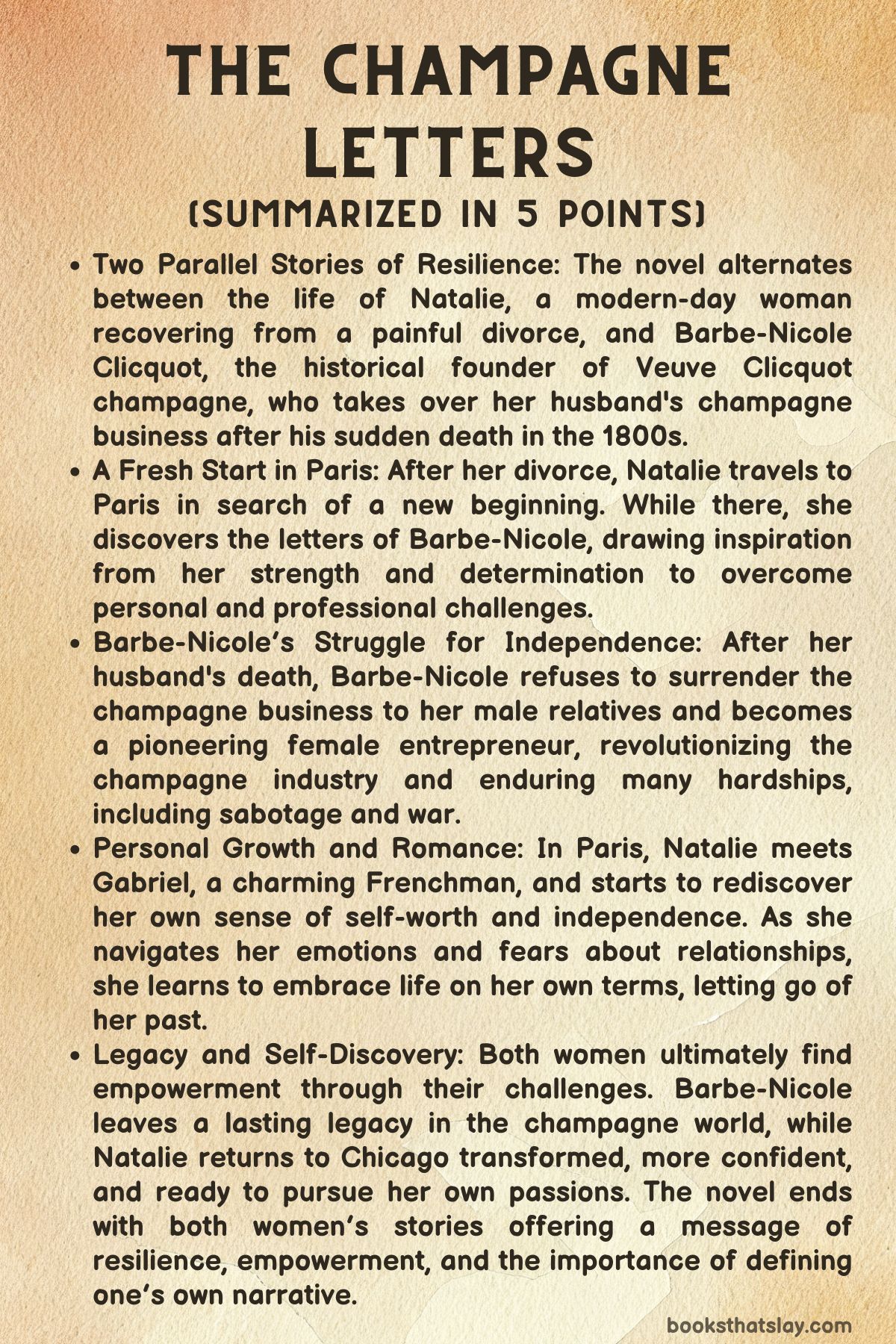

The Champagne Letters by Kate Macintosh is a dual narrative that explores the inner lives of two women from vastly different centuries—Barbe-Nicole Clicquot, the real-life 19th-century champagne widow and innovator behind Veuve Clicquot, and Natalie, a modern-day American woman navigating post-divorce disillusionment. Through letters, romance, deception, and self-discovery, the novel examines how women carve out space for ambition, healing, and identity in worlds largely controlled by men.

As both protagonists face betrayals and reckon with personal loss, they are forced to choose between retreating into safety or embracing risk. Their stories resonate across time, offering a rich meditation on resilience and reinvention.

Summary

The novel opens with Barbe-Nicole Clicquot writing to her great-granddaughter Anne. Determined to preserve the truth of her life before others reinterpret it through a male-centric lens, Barbe-Nicole begins recounting her past.

Following the sudden and ambiguous death of her husband François, she faces immediate suspicions of arsenic poisoning. Rather than yielding to grief, she takes control of the situation, concealing evidence to protect her husband’s legacy and safeguard their struggling champagne business.

Her response reveals a strategic mind and an unrelenting will to survive. She understands that as a widow in 19th-century France, sentimentality cannot compete with the practical demands of leadership.

In a parallel present-day storyline, Natalie, a fifty-something woman from Chicago, is undergoing a dramatic personal transformation after her husband Will leaves her for another woman. She finds herself displaced, both emotionally and physically, as she is forced to move out of her home and contend with a future she never planned.

Clinging to routines and mantras from self-help books, she struggles to reestablish a sense of control. When Will returns to collect his things, their interaction turns volatile.

In a moment of rage and impulsivity, Natalie declares she is going to Paris.

This spontaneous declaration becomes real, launching Natalie into a new chapter. In Paris, she stays at an expensive hotel and befriends Sophie, the in-house wine expert.

Sophie introduces Natalie to the story of Barbe-Nicole, and Natalie becomes captivated by the widow’s bravery and ingenuity. As Natalie explores the city, she discovers a rare book of translated letters from Barbe-Nicole, which quickly become a source of emotional and philosophical guidance.

Her encounter with Gabriel, a charismatic wine distributor, introduces a romantic thread to her journey. Gabriel encourages her to let go of her past, suggesting she sell her wedding ring and buy something symbolic of her new self.

The narrative of Barbe-Nicole deepens as she recounts the challenges of building her champagne empire during the Napoleonic wars. She risks everything to improve production quality, refining techniques and standing firm in her standards despite sabotage, gossip, and sexist resistance.

Her staff refers to her as “the Crow” due to her somber appearance and stern demeanor. Though harsh, her decisions are always in service of preserving her brand and her daughter Clémentine’s future.

She refuses to remarry, even when pressed by family and business associates, and sells her own jewelry to keep her business afloat.

A central thread in her story is the contentious relationship with her former maid Margot, whom she had manipulated and later dismissed during a difficult time. When Margot reappears with warnings about political instability and asks for help for her son, Barbe-Nicole offers limited assistance—agreeing to take in the boy but refusing to fully acknowledge her past misdeeds.

It’s a moment that exposes her inner conflict between duty and conscience.

Natalie’s story takes a sharp turn when Gabriel disappears. She learns that he and Sophie were con artists who orchestrated an elaborate wine scam, including the theft of her engagement ring.

Natalie is humiliated, questioned by the police, and deeply shaken. But rather than fall apart, she begins to channel her anger into purpose.

Inspired by Barbe-Nicole’s letters, she heads to Reims to trace Gabriel’s origins. Reconnecting with Sophie, who was also abandoned by Gabriel, Natalie proposes a new path: she will help Sophie rebuild her wine shop and uncover the truth behind Gabriel’s deceptions.

Back in Barbe-Nicole’s time, her most daring move is the secret smuggling of 10,000 bottles of her 1811 vintage—nicknamed the “comet wine”—to Russia during wartime. Despite blockades and political danger, the shipment reaches Königsberg and becomes a sensation.

The wine’s success secures Veuve Clicquot’s place in the European market and earns the praise of the Russian czar. It is her defining triumph, one born from unflinching resolve and a willingness to embrace extraordinary risk.

Later, Barbe-Nicole is hit with devastating news: Margot has died, and her final years were filled with hardship. Wracked with guilt, Barbe-Nicole takes steps to support Margot’s orphaned son and begins charitable efforts in Margot’s memory.

This act of restitution signals a shift from purely strategic decision-making to a deeper reckoning with her past.

In the modern arc, Natalie tracks Gabriel through clues tied to Haut-Palmer, a vineyard he once mentioned. Her journey is not just about retribution, but self-restoration.

She drafts a list of goals—chief among them: stop being a doormat and make Gabriel pay. Her efforts culminate in a symbolic confrontation.

Rather than pressing charges, she negotiates the return of her money and establishes moral control over her narrative. Natalie’s decision to buy a new ring—possibly one containing a piece of Barbe-Nicole’s brooch—signifies her reclaiming of agency.

It is not about replacing a lost love but declaring her independence.

The novel closes with Barbe-Nicole’s final letter in 1866. She reflects on a lifetime of ambition, loss, and success.

She offers Anne the same advice she lived by: be bold, pursue your dreams, and never let others define your path. Meanwhile, Natalie, now rejuvenated and resolute, prepares to return home—not to resume her old life, but to begin a new one.

She leaves Barbe-Nicole’s book behind in her hotel room, hoping the next woman who needs courage will find it.

In both storylines, the protagonists face betrayal, societal constraint, and emotional turmoil. But through calculated risk, unshakable resolve, and a fierce commitment to self-determination, they carve out identities that refuse to be defined by others.

Whether through wine, fashion, or personal relationships, both Barbe-Nicole and Natalie reclaim their voices. Their stories, though separated by two centuries, illustrate the timeless nature of feminine resilience and transformation.

Characters

Barbe-Nicole Clicquot

Barbe-Nicole Clicquot stands at the heart of The Champagne Letters as both a historical figure and a symbol of indomitable feminine resolve. Her narrative is framed as a series of letters to her great-granddaughter Anne, a structure that underscores her desire to reclaim her legacy from the distortions of male-dominated history.

Widowed under suspicious circumstances—with a bottle of arsenic discovered near her husband’s deathbed—Barbe-Nicole quickly silences speculation and takes control, choosing survival and business preservation over personal mourning. This decision foreshadows a life ruled by strategic risk, emotional restraint, and an unyielding pursuit of excellence.

Navigating the turbulence of Napoleonic France, Barbe-Nicole forges ahead in the male-dominated wine industry with tenacity. She is resourceful, devising innovative techniques like riddling to clarify champagne and circumventing wartime embargoes to deliver her wine to Russian markets.

Her willingness to smuggle wine across hostile borders, risking imprisonment or ruin, illustrates a courage that is both literal and entrepreneurial. Yet this valor is not without personal cost.

Her complicated relationship with her maid Margot—whom she manipulates, fires, and later grieves—reveals a woman who chooses ambition even when it corrodes her sense of compassion. The return of Margot and her child prompts a reckoning, not just with Barbe-Nicole’s actions but with the emotional toll of leadership.

Her later gestures of charity and support for Margot’s son signal an attempt to reconcile past wrongs with present conscience.

Throughout her life, Barbe-Nicole resists being defined by patriarchal expectations. She refuses arranged marriage proposals, sells her jewelry to fund her business, and dresses in widow’s black not only for mourning but as an armor of seriousness and authority.

Her relationship with her daughter Clémentine further reflects her values: she teaches resilience and political grace, especially during their dignified hosting of Napoleon himself. In her final letter, composed in old age, she exhorts Anne to be fearless and self-reliant.

Thus, Barbe-Nicole emerges as both mentor and matriarch—a woman who constructed a legacy from audacity and survival, insisting that female ambition was not only valid but vital.

Natalie Taylor

Natalie Taylor’s journey in The Champagne Letters serves as the contemporary echo of Barbe-Nicole’s legacy, unfolding with painful relatability in a modern setting. A recently divorced insurance analyst from Chicago, Natalie begins the novel amidst emotional wreckage: her husband Will has left her for a younger woman, and she finds herself packing away not just her belongings but her identity.

She clings to routines—labeling boxes, repeating therapy mantras, obsessing over dietary choices—as a means of reclaiming control over a life suddenly out of her hands. Sarcastic yet deeply wounded, Natalie hides her vulnerability behind a mask of competence, supported only by her fiery friend Molly.

Her impulsive decision to travel to Paris after a bitter confrontation with Will becomes the catalyst for transformation. In France, Natalie is drawn into the world of Barbe-Nicole Clicquot through a series of serendipitous encounters.

The letters she discovers begin as historical curiosities but soon function as emotional lifelines, allowing Natalie to view her own crisis through the lens of another woman’s endurance. The initial glamour of Paris is soon shadowed by betrayal when she is conned by Gabriel—a man who seduces her emotionally and financially under the guise of romance and shared passion for wine.

This betrayal mirrors her earlier experience with Will, but Natalie refuses to fall apart.

Instead, she reinvents herself. With insight and strategic boldness borrowed from Barbe-Nicole, Natalie tracks down Gabriel and Sophie (his accomplice) and forces a reckoning.

Not through violence or legal action, but through clever manipulation and a daring business proposal that puts her back in control. She regains her stolen money, reclaims her dignity, and even finds the courage to replace her lost engagement ring with a phoenix-shaped talisman—an emblem of rebirth.

Natalie’s final moments in France are ones of clarity and purpose: she acknowledges past pain without letting it define her, steps into new ventures with agency, and leaves behind Barbe-Nicole’s letters for another woman who might need them. Her transformation is not instantaneous, but earned through failure, discovery, and ultimately, choice.

Gabriel

Gabriel begins as a seemingly minor but transformative presence in Natalie’s Parisian sojourn. Presented initially as a suave French wine distributor, he embodies the romance and sophistication that Natalie craves after years of emotional neglect.

His attentiveness, sensual intelligence, and encouragement for Natalie to reclaim her identity (symbolized by his suggestion she sell her wedding ring and buy something new) make him appear to be a kindred spirit. In him, Natalie sees the possibility of beginning again—not as a woman rebounding from divorce, but as someone truly seen and desired.

However, Gabriel is ultimately a con artist, part of a duplicitous scheme alongside his wife Sophie. His betrayal stings not only because it is financial but because it plays on Natalie’s deepest vulnerabilities—her longing for affirmation, spontaneity, and intimacy.

Gabriel is the mirror opposite of Barbe-Nicole’s steadfast Louis: where Louis risks his life to support Barbe-Nicole’s smuggling operation, Gabriel exploits trust to serve his own gain. His arc reveals the ease with which charisma can camouflage exploitation and the necessity of discernment in the process of self-reclamation.

Though absent in the novel’s second half, his impact lingers, shaping Natalie’s decision to act, reclaim power, and reject victimhood.

Sophie

Sophie is a deceptively soft figure who first appears as a gracious hotel wine steward, guiding Natalie through Paris with quiet elegance and support. Her genuine-seeming kindness builds trust with both Natalie and the reader.

But her eventual revelation as Gabriel’s wife and partner in deception recontextualizes everything. Sophie represents a more insidious betrayal—one of woman against woman, of apparent solidarity turned into manipulation.

Her motives remain ambiguous; perhaps she views their cons as a means of survival, or perhaps she resents women like Natalie who move through life with perceived privilege.

Despite her duplicity, Sophie is not rendered as a one-dimensional villain. Natalie recognizes in her a similar longing for agency, and in their final confrontation, she offers Sophie a choice: repay the stolen money or face exposure.

Sophie chooses restitution, signaling a degree of conscience. This decision creates a space for both women to disengage from cycles of deceit and loss, if not quite redeem themselves.

Sophie’s presence complicates the moral binary of the narrative, suggesting that resilience and reinvention are not reserved solely for the virtuous.

Margot (“the Mouse”)

Margot, nicknamed “the Mouse,” is one of the most morally complex characters in Barbe-Nicole’s story. As a young, pregnant maid in the widow’s household, she represents the vulnerability of lower-class women in early 19th-century France.

Initially dismissed by Barbe-Nicole—who subtly engineers Margot’s departure for the sake of propriety and business—Margot returns later, worn by hardship and seeking help. Her pleas to stay are refused, though Barbe-Nicole provides severance and reference, attempting to mitigate the cruelty of her choice.

Margot’s later reappearance with her son marks one of the story’s most searing emotional confrontations. She accuses Barbe-Nicole of hypocrisy, of sacrificing compassion for ambition.

Their clash is raw and unresolved, laying bare the power dynamics between mistress and servant, woman and woman. After Margot’s death, her memory haunts Barbe-Nicole, compelling her to support the boy and channel guilt into tangible good.

Margot becomes both a victim of ambition and a moral compass, forcing Barbe-Nicole to face the cost of her rise.

Molly

Molly is Natalie’s anchor in the modern world—a brash, fiercely loyal friend who insists on truth when Natalie prefers avoidance. She embodies the voice of unfiltered honesty, urging Natalie to stop wallowing and start reclaiming her life.

Initially dismissed as intrusive or overbearing, Molly’s emotional intelligence becomes clearer as Natalie matures. Her presence helps Natalie recognize the ways she has used control to mask pain and the necessity of vulnerability in healing.

Their relationship is strained but ultimately resilient. Molly’s unwavering support and capacity to forgive reveal the value of true friendship, especially when romantic connections falter.

She offers a grounded counterpart to Natalie’s Parisian adventure, ensuring that transformation is not only dramatic but also sustainable.

Louis

Though a more peripheral figure, Louis plays a pivotal role in Barbe-Nicole’s success. Loyal and brave, he volunteers to smuggle the champagne to Russia during wartime, risking imprisonment and death.

Louis represents the ideal ally: one who recognizes and supports a woman’s leadership without resentment or patronizing doubt. His faith in Barbe-Nicole’s vision and his willingness to put himself in danger for her dream exemplify the trust that undergirds genuine progress.

He is the quiet hero behind the scenes, a foil to the opportunistic men who try to manipulate Barbe-Nicole into marriage or financial dependence.

Together, these characters form a rich tapestry of ambition, betrayal, grief, and regeneration.

Themes

Female Autonomy and the Reclamation of Self

Barbe-Nicole and Natalie each represent different epochs, yet their struggles center around the same core need: to reclaim control over their lives when it has been taken or undermined by others. Barbe-Nicole, widowed young and surrounded by male advisors eager to steer her future, faces societal norms that expect her to remarry and relinquish her business.

Her response is not simply defiance but a carefully considered assertion of her capability and entitlement to chart her own course. She chooses to sell her jewelry to fund her champagne business instead of entering a transactional marriage.

That act transforms personal grief into empowerment, an economic statement that she does not require a man to validate her decisions. Natalie, though modern, faces her own erasure through decades of emotional atrophy in her marriage.

Her husband’s abandonment reopens the question of who she is when she is not fulfilling someone else’s expectations. Her journey to Paris, her wardrobe reinvention, her embrace of sensuality and solitude—these are not whims but vital expressions of autonomy.

Both women reject roles imposed upon them and choose their identities anew. Barbe-Nicole’s refusal to let her husband’s suicide define her, and Natalie’s refusal to let Gabriel’s betrayal crush her, form a shared ethos: the reclamation of self is not a single act but a continuous decision to remain unapologetically sovereign.

Risk as a Catalyst for Transformation

Every significant shift in both women’s lives is preceded by a bold, risky choice. For Barbe-Nicole, smuggling champagne to Russia during wartime, against all logistical and legal odds, becomes a turning point.

It is an audacious act that could have resulted in financial ruin, but her willingness to gamble everything is born not from recklessness but from the understanding that change demands action. She operates in a volatile political climate, with trade routes blocked and male competitors circling, yet she persists.

Her decision to entrust Louis with the shipment and to quietly maneuver around authorities proves decisive. Similarly, Natalie’s decision to confront Sophie and Gabriel, after discovering their con, marks her own transformation.

She eschews traditional revenge or legal intervention and instead creates a new path—reclaiming her power through negotiation and business acumen. Risk for her initially manifests in smaller steps: traveling to Paris on a whim, staying in a hotel she cannot afford, and speaking to strangers.

These acts accumulate until she is capable of orchestrating her own form of justice. Neither woman is immune to fear or failure, but their capacity to risk—emotionally, financially, personally—is what births the lives they ultimately claim.

Risk, in this narrative, is not merely a plot device; it is a form of declaration, a necessary disruption that makes renewal possible.

Grief, Guilt, and Emotional Compartmentalization

Emotional pain is not portrayed as something that dissipates quickly or fully heals. Instead, grief and guilt remain present forces that both women learn to live alongside.

Barbe-Nicole’s grief over her husband’s death is complicated by the ambiguity of the arsenic bottle, the rumors of suicide, and her deliberate choice to conceal this truth. Her grief cannot follow a natural path; it is suspended, restructured into ambition and strategy.

Later, her guilt over Margot—the maid she manipulated and ultimately dismissed—continues to haunt her. She never fully admits the depth of her responsibility, even when Margot confronts her years later, but she channels that guilt into quiet reparations, supporting Margot’s son and funding charitable work.

These gestures do not erase the past, but they allow Barbe-Nicole to acknowledge its weight without becoming immobilized by it. Natalie’s emotional wounds are fresher, yet she, too, compartmentalizes.

Her sarcasm and therapy mantras are defense mechanisms; labeling boxes and controlling her environment become coping strategies. Her betrayal by Gabriel deepens her sense of shame, yet instead of wallowing, she transforms it into a mission—both to recover her stolen dignity and to build something from the ruins.

The narrative does not offer easy catharsis. Instead, it emphasizes that grief and guilt linger, reshaping but not erasing the women they inhabit.

The resolution is not peace, but purpose.

Identity through Objects and Ritual

Objects take on outsized meaning in The Champagne Letters, becoming physical representations of emotional evolution. Barbe-Nicole’s jewelry is not merely ornamental; it is both currency and legacy.

When she sells it to finance her champagne venture, it is not just an economic transaction—it is a renunciation of security in favor of self-determination. The bottles of comet wine, hidden and then smuggled, are not simply inventory; they symbolize her daring and her faith in her product during one of France’s most unstable periods.

For Natalie, the objects she clings to in the wake of her divorce—wedding rings, curated furniture, old routines—symbolize the version of herself she is trying to escape. Her eventual act of selling the ring to purchase a necklace bearing a phoenix transforms the object from an emblem of failed commitment to one of rebirth.

Her new ring, potentially crafted from Barbe-Nicole’s brooch, becomes the narrative’s full circle—a relic passed across generations to reinforce the enduring need for women to possess symbols of their autonomy. Even the shared experience of wine—Barbe-Nicole’s business and Natalie’s seduction—becomes ritualistic, a medium through which identity is affirmed and reclaimed.

Rituals like listening to classical music in the garden or toasting victories are not indulgences; they are ways of reaffirming control and presence in a world that often marginalizes women’s interior lives.

Historical Echoes and Feminine Lineage

The novel constructs a powerful sense of feminine continuity across centuries, with Barbe-Nicole’s letters acting not only as narrative bridges but also as spiritual guides. Natalie’s discovery of these letters at a time when she feels lost is no accident—it is positioned as a passing of wisdom from one generation to another.

This transmission is not biological, as the women are not related, but it is emotional and ideological. Barbe-Nicole’s words offer Natalie more than inspiration; they offer a framework for survival, rebellion, and self-respect.

The letters contain candid accounts of doubt, anger, triumph, and regret, giving Natalie permission to feel without apology. In turn, Natalie leaves the book behind for the next woman, continuing the chain.

This symbolic bequeathing situates women’s stories not as isolated or disposable, but as part of a lineage of struggle and courage. The past is not just a backdrop to Natalie’s present but an active influence that shapes her decisions and redefines her beliefs about what women are capable of.

The intergenerational aspect of feminine resilience, transmitted not through birthright but through choice and attention, suggests that legacy is built through shared narratives, not inherited roles. The book becomes a testament to how history, when told truthfully and unapologetically, can equip future generations to resist, recover, and rise.