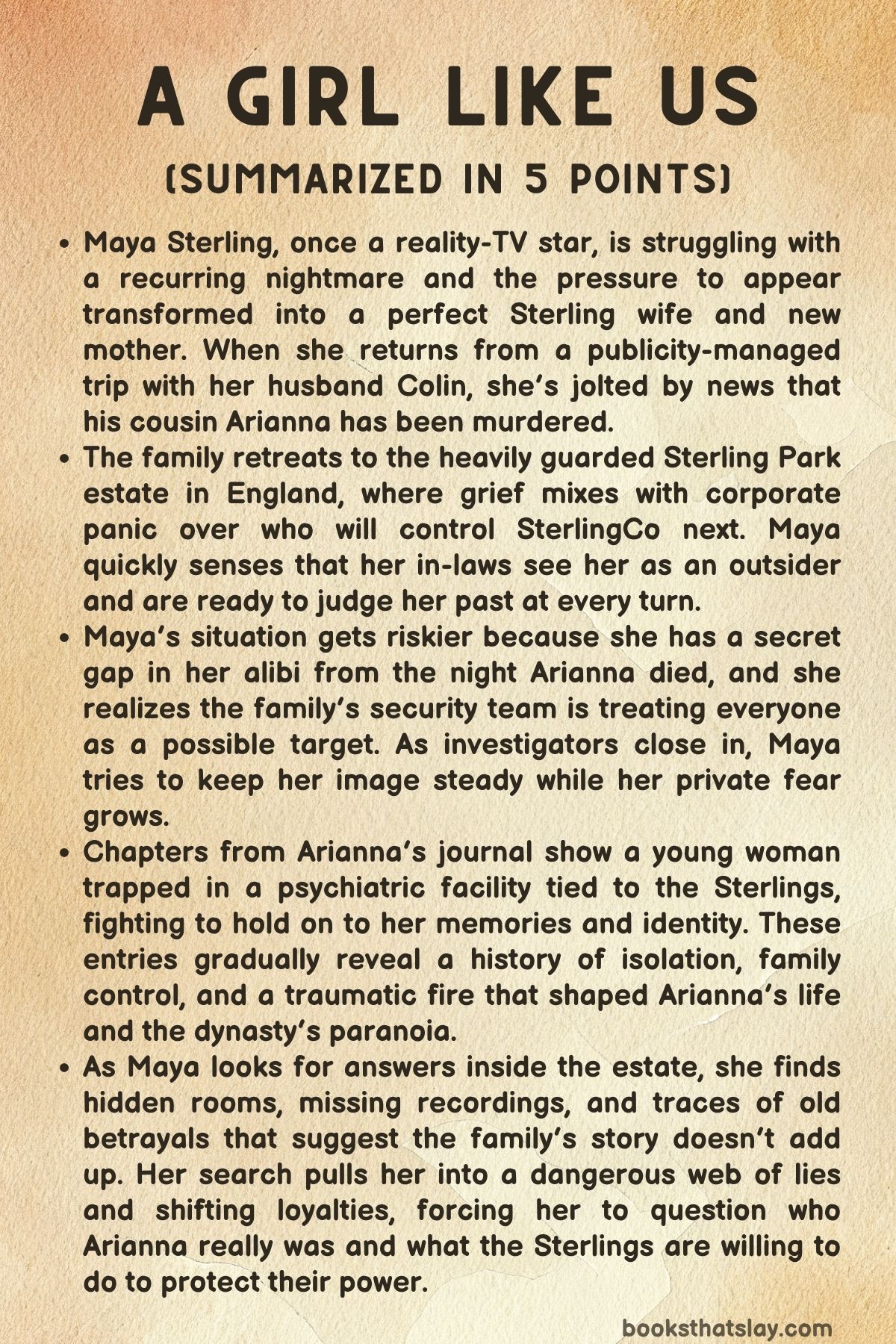

A Girl Like Us Summary, Characters and Themes

A Girl Like Us by Anna Sophia McLoughlin is a glossy, high-stakes psychological thriller set in the early 2000s, where celebrity culture and old-money power collide.

The story follows Maya Sterling, a former reality-TV firecracker who has tried to reinvent herself as a respectable wife and new mother inside the intimidating Sterling dynasty. When a young heiress is murdered, Maya is pulled into a locked-down estate, a bitter inheritance war, and a maze of family secrets. Alternating viewpoints and timelines reveal how fame can be weaponized, how institutions can silence women, and how one “outsider” might be the only person capable of exposing the truth.

Summary

Maya Sterling, once known to the world as Maya Miller from the hit reality show The Springs, is four months postpartum and exhausted. She keeps waking from a recurring nightmare that drags her back to her early fame: paparazzi chase her through city streets while a cruel voice brands her a fraud and a gold digger, even leaving that insult tattooed across her skin. The dream mirrors her deepest fear—that no matter how much she changes, the world and the Sterling family will always reduce her to a scandalous past.

In 2004, Maya flies home to New York with her husband Colin Sterling and their baby, Becca, after a carefully choreographed trip to Puerto Vallarta. The trip mixed their quiet wedding with SterlingCo business, and Maya has been trying to perform a new role: poised corporate wife, loyal mother, safe choice.

Yet on the yacht she endured invasive questions from executives’ wives about sex on television, her body after pregnancy, and whether she schemed her way into the dynasty. She tells herself she loves Colin and that stability has softened her old chaos, but her confidence is thin.

As their jet lands near New York, the atmosphere turns strange. Security boards immediately, removes the nanny, and orders the family back into the air under “protocol 202.” Colin announces they must go to England because a cousin has died. Then the truth lands harder: Arianna Sterling, the family’s reclusive heiress, has been murdered in Puerto Vallarta that morning.

Maya is stunned. She barely knew Arianna existed. Colin explains that Arianna was raised almost in isolation by her paranoid father Harry after a lethal fire years earlier at a Sterling property in the Seychelles. When the family later reconnected, Arianna struggled with addiction, tabloid attention, and conflict with Harry, before disappearing from public life.

Security chief Travis says Arianna was found strangled in a high-rise called the Mismaloya, with signs of forced entry and a struggle. No suspect is known, and every Sterling is now a possible target. Everyone needs a clear alibi. Maya’s stomach drops, because the night before the murder she slipped off the yacht alone after receiving a text from a blocked number.

She met someone briefly at an Iguana Bar, hidden under a hat and speaking Spanish fluently. She believed no one saw her. Now she realizes that if the meeting is exposed, her marriage, her custody of Becca, and maybe her freedom could vanish.

Sterling Park in England is less a home than a fortress.

Armed guards, locked gates, and rituals of status remind Maya she is still on probation inside this family. Aunt Helen Sterling, the matriarch, dominates the estate with steel manners and a long memory. Maya remembers their first encounter vividly: Helen forced her to sign a strict prenup on the spot, threatened Colin’s trust position if she refused, and mocked her as a money-seeker while gifting her a pickaxe charm as a joke. That humiliation never left Maya.

At Silver House, the estate’s central mansion, Maya walks into a salon filled with blood relatives who greet her with chilly politeness. CEO cousin Marcus Sterling is present with his wife Eva and their children.

Colin’s sister Gigi, blowy and sharp-tongued, offers Maya a drink and comic warnings about the house politics. Eva needles Maya by showing a celebrity magazine mocking her and by remarking on her travel clothes. Maya stays calm, but feels like a specimen under glass.

Julian Lambert-Sterling, Helen’s husband, arrives loud and charming. He says no one knows where Harry is. The room tightens when Maya asks. Harry has been vanishing for years, still haunted by the old fire and suspicious of assassination plots. Colin brings Maya upstairs to their old nursery suite, where servants have already unpacked Becca.

Colin jokes about “training” Maya to let staff handle everything. The joke carries a quiet threat: she must adapt, or be defined as unfit.

That night Maya misses dinner after oversleeping. Wandering the corridors with Becca, she is drawn to a portrait of a small girl she believes is Arianna. She climbs to a garret that seems to have been Arianna’s childhood room. For a moment she thinks she sees Arianna’s face in a mirror, but it’s Helen, grief-stricken and furious. Helen describes Arianna as controlled, lonely, and damaged by Harry’s rule. Then she snaps back into cold authority and sends Maya to bed. Maya pockets one of Arianna’s dolls, unsettled by how much of the girl’s life feels like captivity.

Intercut with Maya’s present is the voice of a woman confined in Portas Brancas, a psychiatric facility bankrolled by Sterlings. The woman resents her medication, believes her family wants her erased, and writes in a journal to keep track of what is real. She remembers teenage years at Sterling Park, wild nights with Gigi, and a sense of freedom that was abruptly cut off when Harry decided she needed to be molded into a proper Sterling. After a panicked attempt to escape, she was restrained and institutionalized.

Her memories begin to hint that this woman is Arianna herself, alive somewhere behind locked doors.

Morning brings legal war. Family counsel Rory Atkinson reports that Arianna’s death looks like a botched kidnapping. Helen orders Maya out of the room so blood relatives can discuss the trust.

On a walk, Julian bluntly explains that Harry transferred huge SterlingCo shares and Sterling Park ownership to Arianna in advance, making her the future controller of the empire. With her dead and Harry missing, everything is up for grabs.

The investigation tightens around Maya when an agent presents a photo of Maya with Arianna in Mexico shortly before the murder. Maya insists she met the woman only briefly, thinking she was a journalist named Jessie Moore. Worse, that woman left her fortune to Maya.

The family reads this as manipulation. Colin wants to protect Maya but is torn by the dynasty’s pressure.

Searching for clarity, Maya sneaks into Harry’s abandoned study and finds a hidden child-sized cubby containing Arianna’s childhood drawings and dozens of cassette tapes labeled only with initials.

Under a floorboard she discovers keepsakes engraved with the name Mikey Blackburne, Harry’s old friend who supposedly died in the La Digue fire. Eva catches her and warns her that Harry monitors everything, even from afar. Maya feels the trap closing.

Flashbacks reveal Maya’s own buried link to Portas Brancas. At the height of her reality-TV fame, she had an explosive affair with Marcus Sterling, spiraled into public humiliation, blacked out, and was arrested. SterlingCo lawyers cleaned it up and secretly sent her to Portas Brancas to bury the scandal. There, Maya briefly overlapped with a fragile young woman who adored her show and seemed desperate to be believed. Maya never knew that woman was Arianna.

Pieces accelerate after a skating spectacle at the estate ends in panic. Maya glimpses Harry inside Silver House and notices cuff links engraved with the same Blackburne insignia as Mikey’s keepsakes.

When she runs back to the study, the tapes are gone. She concludes someone is cleaning evidence and begins to suspect that “Harry” is not Harry at all, but Mikey Blackburne who survived the fire and assumed Harry’s identity.

Maya races to Arianna’s garret and finds a hidden Blake book stuffed with notes, a drawing of two blond girls labeled Arianna and Jessica, and a repeated line: “The eye of the tiger.” She searches the tiger-patterned wallpaper for a cache. Julian appears, pours a drink, and stays too close.

Maya grows dizzy. Julian admits he helped drug her years ago to remove her from Marcus’s life, and now he needs to know what Arianna told her in Mexico. He is sure no one will trust Maya because her past labels her unstable. A brutal fight erupts. Behind torn wallpaper, a small tape recorder is revealed. Julian grabs it, preparing to silence Maya permanently.

A scar-faced woman bursts in and stabs Julian dead. She is Caro, the vanished therapist from Portas Brancas. She drags Maya through hidden tunnels to a remote cabin. There, revelations land with terrifying precision.

The woman Maya met in Mexico was not Arianna Sterling but Jessica Blackburne, raised under Arianna’s name. The tape recorder holds a confession: Mikey Blackburne and Helen planned the La Digue fire to kill the real Harry, never expecting a child to die. They then removed the real Arianna and positioned their daughter Jessica as the heiress, consolidating control over SterlingCo.

Caro is the real Arianna, saved from the fire by a nanny who later died after delivering evidence of Sterling crimes. Arianna had rescued Jessica from Portas Brancas and sent her to Maya because Maya’s media power could expose the family. Julian found Jessica first in Mexico and killed her.

Helicopters and dogs close in. Maya chooses to protect Arianna and the evidence. She sets Mikey’s watch alarm on Arianna to wake her, pockets the confession tape, and runs into the snow screaming for help to pull searchers away.

The aftermath is polished for the public. Julian’s London funeral is presented as a tragic accident during an intruder scare. “Harry” disappears abroad after signing papers validating Jessica’s will that places control in Maya’s hands. Maya confronts Helen privately, making it clear she knows the truth and will ruin the dynasty if threatened. Colin learns everything and vows to protect his wife and child.

Marcus attempts to rekindle his old hold over Maya, but she refuses. Maya leaves England with her daughter and with copies of the confession hidden in the estate. Arianna remains free and underground, while Maya holds the secret leverage that can destroy the Sterlings whenever she chooses.

Characters

Maya Sterling (formerly Maya Miller)

Maya is the novel’s volatile center, a woman trying to outgrow the persona that made her famous while discovering how little control she truly has over the story others tell about her. She enters the Sterling world carrying two identities that never quite fuse: the carefully curated “corporate wife and mother” she wants to be, and the old reality-TV “Miss Mayhem” whose survival depended on conflict, spectacle, and self-reinvention.

The recurring nightmare of being branded a “gold digger” is not just trauma flashback but a map of her deepest fear—that no matter what she builds, she will always be reduced to a scandalous origin story. Her secret midnight meeting in Puerto Vallarta shows the same pattern: even in motherhood, she is drawn to risk and secrecy, and those impulses become the lever the Sterlings use to doubt and control her. Maya’s strength is her perception; she reads tone, posture, symbols, and power games with a practiced media instinct, which lets her notice fractures in the family myth long before anyone else.

Yet that same instinct is sharpened by a lifetime of public shaming, making her hypervigilant and easy to gaslight. Her arc is about reclaiming authorship: by the end she chooses strategy over apology, using evidence and narrative power as protection for herself and Becca, and transforming from someone the family can erase into someone the family must fear.

Colin Sterling

Colin embodies the Sterling paradox of gentleness wrapped in inherited brutality. On the surface he is the safe choice Maya married—steady, affectionate, and seemingly less predatory than his relatives—yet his loyalty is split between wife and dynasty, and that split defines his role. Colin’s protectiveness is real, but it often arrives in the family’s language of “protocols,” locked rooms, and controlled information, suggesting he is both shield and gatekeeper.

His childhood memory of fear, the tiger wallpaper, and the poem he recites reveal a man shaped by old terror and by a family culture that punishes weakness; he learns early to survive by obedience. Colin does not drive the conspiracy, but he benefits from it, and his hesitations show how even the “good” Sterling is conditioned to preserve the machine.

When Maya is doubted, he wavers—not because he doesn’t love her, but because the family has trained him to treat scandal as existential threat. His eventual alignment with Maya against Helen is a late but meaningful rupture: Colin’s love becomes active rather than passive, and he finally chooses his created family over the inherited one.

Becca Sterling

Becca is small in page time but huge in symbolic weight, functioning as Maya’s anchor to reality and to the future she refuses to let the Sterlings corrupt. Every time Maya is pulled toward old chaos or spirals into paranoia, Becca’s needs drag her back into the present.

The baby also raises the stakes of the family war: Maya’s fear is no longer about survival alone, but about whether her daughter will inherit a life of surveillance, reputational violence, and dynastic bargaining. Becca’s quiet presence reframes Maya’s choices from personal rebellion to maternal strategy, pushing Maya to become colder, smarter, and more deliberate than the girl the tabloids once mocked.

Arianna Sterling (the girl raised as Arianna, revealed as Jessica Blackburne)

The “Arianna” Maya first hears about is a ghostly heiress shaped by isolation, addiction, and family mythmaking, and her diary voice reveals a person who has been told her own mind is unreliable.

Raised inside Sterling Park as a possession rather than a child, she learns to interpret care as control and affection as captivity, which is why her writing oscillates between longing and sharp distrust. Her neediness, erratic behavior, and addiction are not presented as innate flaws but as the predictable products of suffocation and manipulation. The twist that she is actually Jessica Blackburne deepens her tragedy: her identity was engineered, her inheritance weaponized, and even her death becomes a final move in another person’s game.

Still, she is not merely a victim; she is curious, brave enough to seek truth, and lucid enough to leave evidence. Her reaching out to Maya in Mexico is an act of self-rescue through solidarity, choosing a woman who understands televised myth and public cruelty to carry the truth forward.

Caro

Caro is the novel’s hidden blade—first appearing as a threatening, scar-faced pursuer, then revealed as the true Arianna, survivor of a childhood attempt on her life. Her hardness comes from living as both hunted and erased; she exists outside the Sterling narrative because the family needs her to be dead for their story to work. Caro’s moral compass is blunt and survival-driven: she trusts actions over words, moves through tunnels and snow with the practiced reflex of someone who has spent years preparing for betrayal.

Her rescue of Jessica from Portas Brancas and her killing of Julian show that she is willing to use violence to protect truth, yet she is not driven by cruelty so much as by the refusal to be rewritten again. Caro also functions as Maya’s dark mirror—another woman labeled unstable and dangerous, fighting back against institutional gaslighting. Where Maya wields media and social performance, Caro wields secrecy and direct force; together they represent two routes to female survival in a world that profits from calling women “crazy.”

Helen Sterling

Helen is the dynasty’s iron core, a woman who converts class prejudice into personal cruelty and uses tradition as camouflage for power grabs. Her first meeting with Maya shows her operating on instinctive dominance: she forces the prenuptial agreement, threatens Colin’s financial standing, then gifts a pickaxe charm as a performative insult meant to brand Maya forever. Helen’s grief for Arianna is genuine in a narrow way—she loved the girl she knew—but it never overrides her primary religion: control of SterlingCo and the family name.

The confession tape reveals her as an architect of the original sin, willing to orchestrate murder, child-switching, and institutionalization to secure inheritance. What makes her frightening is not just her ruthlessness but her certainty; she believes she is protecting a natural order where Sterlings rule and outsiders are expendable. By the end, she is trapped in a stalemate with Maya, suggesting that even predators can be caged when their narrative monopoly breaks.

Julian Lambert-Sterling

Julian is charm as a weapon, the family’s smiling face with something rotten behind the eyes. He performs warmth toward Maya—jokes, drinks, grandfatherly talk—yet every kindness is also surveillance, a way to keep her close and uncertain. His role in drugging Maya twice, years apart, reveals a pattern of institutional male control over female bodies, especially bodies that threaten the family’s image.

Julian believes in the Sterling right to erase scandals and people alike, and he treats Maya as a problem to be managed, not a person to be heard. His arrogance is his downfall: he assumes the family’s history of labeling women unstable will protect him, which lets Caro strike. His death is narratively satisfying not because he is the greatest villain, but because he is the most immediate embodiment of the family’s predatory entitlement.

Marcus Sterling

Marcus represents the Sterling appetite without restraint, a man who treats desire and dominance as the same thing.

His affair with Maya during her reality-TV peak is not a romantic detour but a power experiment: he pulls a famous outsider into his orbit, then lets the family machinery punish and remove her when she becomes inconvenient. His later attempts to rekindle the relationship after Julian’s death show his refusal to accept boundaries, and his confidence that old emotional leverage will still work.

Marcus’s significance is structural—he is proof that the Sterlings’ corruption is not limited to one mastermind but is cultural, passed down as privilege and practiced as sport.

Regina “Gigi” Sterling

Gigi is the wild nerve of the family, shaped by grief, isolation, and a taste for escape. Losing her parents to a paparazzi-fueled helicopter crash makes her both a victim of celebrity cruelty and someone who weaponizes irreverence to survive it. Her friendship with young Arianna/Jessica is genuine; she offers tunnel adventures and nights out not to corrupt her cousin but to give her air.

Yet Gigi’s adulthood is messy and evasive, and her ability to sneak out during lockdown hints at knowledge she won’t fully share. She sits at a crossroads between complicity and rebellion: she hates Sterling control, but she also benefits from Sterling protection. Her love is real, her chaos is protective camouflage, and her silence is partly fear of how the family destroys truth-tellers.

Harry Sterling (the real Harry)

The real Harry is mostly absent in the present storyline, but his shadow defines everything. After the La Digue fire he becomes paranoid and isolating, raising the girl he believes is Arianna in fortress-like seclusion.

His paranoia is understandable—someone tried to kill him and succeeded in killing others—yet his response is damaging, creating the cage that fuels his daughter’s breakdown. He is neither pure villain nor saint: his love is fierce but possessive, and his need to control the world to keep his child safe ends up making her unsafe in another way. His disappearance after the murder suggests a man who finally understands the family he feared is worse than the threats outside it.

Mikey Blackburne (posing as “Harry” in the present)

Mikey is the story’s long-con villain, a man driven by envy and ambition who turns survival into conquest. Originally Harry’s friend, he resents the Sterling birthright enough to plan the La Digue fire, gambling on murder as a shortcut to power.

Surviving the blaze, he assumes Harry’s identity with chilling patience, raising Helen’s biological daughter Jessica as Arianna to funnel inheritance toward their line. Mikey’s success depends on two talents: performance and ruthlessness. He can mimic a Sterling patriarch convincingly enough to intimidate the household for years, and he can erase inconvenient people without blinking. His impersonation also makes the theme of identity literal—names and roles in this family are costumes that the ruthless can steal.

Eva Sterling

Eva is the dynasty’s social immune system, policing status at the level of clothes, tone, and insinuation. She greets Maya not with open hostility but with curated contempt—magazines left on tables, remarks about outfits, the subtle collective chill that tells an outsider she will never be family.

Her primary loyalty is to Marcus and to the inheritance fight, and her treatment of Maya is strategic: if Maya is kept insecure and defensive, she stays weak. Eva is not the mastermind of the larger conspiracy, but she is one of its daily enforcers, the kind of person who keeps a corrupt system smooth by making cruelty feel like etiquette.

Barrow

Barrow is the estate’s quiet memory, a servant who has watched generations of Sterlings rise and rot. His loyalty is professional, but his late-night kindness to Maya and his gentle references to Arianna’s nocturnal wandering imply a deeper compassion than the family deserves.

Barrow knows the house’s rhythms, its secret habits, and likely its hidden truths; his role suggests that the real archive of Sterling Park lives not in boardrooms but in the people who keep the lights on. He operates as a subtle moral contrast: even within a machine built on control, individual decency can persist.

Rory Atkinson

Rory is the corporate voice of the family, translating murder and inheritance into legal procedure. He treats Arianna’s death less as grief than as a crisis of optics and assets, arriving with files, press strategies, and trust implications. His frustration when no one speaks about Arianna’s last movements shows he understands the family is hiding something, but his role requires complicity—he is paid to protect SterlingCo, not to uncover truth. Rory personifies the way wealth launders violence through institutions: what is morally monstrous becomes “a matter for counsel.”

Travis

Travis represents the Sterlings’ securitized worldview, where family life is run like a state under siege. He initiates “protocol 202,” removes staff, tracks threats, and assumes murder is not a personal tragedy but a tactical risk to the dynasty.

His professionalism is cold but not malicious; he is doing the job the family requires. Travis’s warnings about targets and alibis increase Maya’s paranoia and expose how quickly security can resemble imprisonment when the people being “protected” are also being watched.

Agent Cetin

Agent Cetin is the external pressure of reality, the investigator whose evidence punctures the Sterlings’ attempt to control the narrative.

By presenting the photo of Maya with Arianna/Jessica, he detonates suspicion inside the household and proves that the family cannot fully seal itself off from law. He is significant less as a fully drawn person and more as a force that turns private secrets into public stakes, accelerating the family’s fracture.

Sarah-Jane

Sarah-Jane, the nurse from Portas Brancas, is a small but crucial hinge between stories, confirming the overlap between Maya and Arianna/Jessica and validating Maya’s memory against the family’s gaslighting.

Her abrupt ending of the call suggests fear, surveillance, or guilt—she knows the institution’s role in the Sterling apparatus and is not free to speak openly. Sarah-Jane shows how deep the family’s influence goes, reaching into medical spaces meant to heal and turning them into tools of erasure.

Themes

Identity as Performance and the Fight for Self-Definition

Maya’s life is shaped by roles that other people write for her, and the pressure to live inside those roles never stops. Long before the murder, she has already learned that fame creates a version of you that the world thinks it owns. Her nightmare makes that explicit: she is not only chased by cameras but by the questions that reduce her to a stereotype.

Even in sleep, the public narrative brands her as a “gold digger,” and the tattoo in the dream shows how labels can feel permanent, like they have been stamped onto the body. In waking life she keeps trying to manage her image—first as the “nice girl” on television, then as “Miss Mayhem,” and now as the polished Sterling wife and new mother. None of these selves is fully fake, but none is fully free either; they are survival strategies for different audiences. The Sterling family repeats the same dynamic at a higher social altitude.

They decide who counts as respectable, who counts as unstable, and who counts as disposable. Arianna/Jessica’s stolen identity pushes that to the extreme: a child is literally renamed and raised to serve a corporate inheritance plan. The person she could have been is treated as irrelevant compared to the usefulness of a title. By connecting Maya’s celebrity reinvention to the family’s identity fraud, A Girl Like Us shows how powerful systems don’t just control money or access; they control meaning. The story keeps asking what is left when the world insists you are a myth: a seductress, a madwoman, an heiress, a scandal.

Maya’s eventual leverage over Helen is a hard-won moment of self-definition. She is no longer only the woman they narrate; she becomes the one who holds the narrative weapon. Identity, here, is not a quiet inner truth. It is a contested space where survival depends on taking back the right to name yourself.

Wealth, Power, and the Machinery of Control

The Sterling empire functions like a private state, complete with protocols, security forces, legal teams, and social rules that everyone must obey. “Protocol 202” is a perfect symbol of that machinery: the family can shut down movement, isolate members, and rewrite reality at will under the excuse of protection.

The public sees luxury and prestige, but inside the fortress the atmosphere is closer to containment than comfort. Wealth becomes the tool that makes coercion polite. When Helen pushes a prenuptial agreement at Maya, it is not just a marital safeguard; it is a reminder that access to the family is conditional and revocable. The same power dynamic controls Arianna/Jessica and Caro. Institutions like Portas Brancas exist as extensions of Sterling authority, allowing the family to lock away inconvenient people while framing it as care. The staff, the doctors, even therapeutic language become part of a larger enforcement system. The family also uses wealth to manage scandal: Maya’s arrest and breakdown are not treated as a personal crisis but as a brand risk to be removed from sight.

Money pays for silence, for travel without tracks, for press delays, and for the creation of alternate identities. What makes this theme hit hard is how ordinary it feels to the Sterlings themselves. They are trained to see dominance as responsibility and secrecy as tradition. Yet the narrative keeps revealing the cost: Caro’s life erased, Jessica’s childhood stolen, Maya’s autonomy constantly questioned, and even Colin’s loyalty tested by the obligations of inheritance. The Sterling world shows that power doesn’t need constant violence to succeed.

It succeeds through systems that make domination seem reasonable. By the end, Maya reverses the direction of control—keeping evidence hidden, refusing Marcus’s pull, and using the family’s own methods against them. The story’s tension comes from watching power operate smoothly until someone inside it decides to stop cooperating.

Misogyny, Sexual Judgment, and the Politics of Reputation

The women in this story are evaluated through a narrow moral lens that men rarely face, and that double standard drives both conflict and fear. Maya’s nightmare is built out of humiliations that have followed her in public life: accusations that she slept her way into success, that she exploited her body, that she fooled her audience. Those taunts reappear in the Sterling estate through Eva’s magazine ambush, Helen’s branding, and Julian’s confidence that no one will believe Maya because of her “history.” In their world, a woman’s sexuality is never just hers; it is evidence to be used for or against her.

The word “gold digger” is the family’s favorite weapon because it collapses Maya’s entire identity into a single motive and makes her love suspect by default. Even motherhood doesn’t protect her from this scrutiny. Instead, the gaze shifts to her body, her weight loss, her private choices, and whether she is performing maternal devotion the “right” way. Arianna/Jessica and Caro face another angle of the same cruelty. Their distress is medicalized quickly, not because care is offered generously but because labeling a woman unstable is a convenient way to neutralize her.

The institution becomes a socially acceptable cage, and medication becomes part of policing. The real danger is not only the men who attack in obvious ways, like Julian drugging Maya, but the broader culture that lets him assume the role of judge. The story shows that reputation is a gendered battleground: men’s secrets become strategy, women’s secrets become shame.

Maya’s arc pushes against this, especially in the epilogue where she refuses to be pushed back into a role—sexual, submissive, or silent. She chooses stability on her own terms and holds the proof that can tear down the people who tried to reduce her. A Girl Like Us exposes how misogyny works less as a single villain’s attitude and more as a shared language that licenses cruelty toward women who don’t stay in their assigned place.

Trauma, Memory, and the Blur Between Care and Captivity

Trauma in this novel is not a past event that characters “get over.” It is a living force that shapes perception, sleep, trust, and bodily reaction. Maya’s recurring nightmare is trauma speaking in symbols: the hotel room, the paparazzi chase, the tattoo, the aunt behind the counter.

It is her mind replaying the shame and loss of control that fame and the Sterlings have brought into her life, especially during the vulnerable period of new motherhood. The dream’s cruelty is that it refuses to stay in the past; it returns every night, reminding her that healing is not linear. Arianna/Jessica’s journal entries show trauma from the other side, inside a facility where memory itself feels threatened.

The fear that medication is wiping her away is not paranoia in a vacuum; it is a response to years of being controlled and disbelieved. The institution’s supposed care carries the feeling of punishment, and the narrative highlights how easily “treatment” becomes a tool to remove inconvenient truth. The line between hallucination and reality is intentionally unstable—not to glamorize confusion, but to show what happens when someone’s experiences have been denied for so long that self-trust erodes.

The Sterling family’s history is trauma layered into legacy: the La Digue fire and its aftermath create paranoia, silence, and cycles of containment. Even Colin exhibits inherited trauma, seen in his childhood fears, remembered ridicule, and instinct to obey protocol. What ties these strands together is the question of who gets to define what is real. Trauma often isolates people by making their inner world hard to communicate; the Sterlings exploit that by framing distressed women as unreliable. Maya’s turning point arrives when she chooses to trust her own perception despite gaslighting and social pressure. Recovering the tape recorder is not just a plot discovery; it is a reclamation of memory.

The story suggests that trauma survives when truth is suppressed, and that healing begins not with forgetting but with naming what happened and refusing the version imposed by powerful caretakers.

Motherhood, Protection, and Female Agency

Maya enters the Sterling world carrying a baby in her arms, and that fact changes the meaning of every risk she takes. Motherhood is not treated as a sentimental subplot; it is the lens through which Maya measures safety, future, and dignity. Her desire to become a “corporate wife and devoted mother” is partly aspiration and partly armor, a way to secure stability for Becca in a world that weaponizes scandal. Yet motherhood also makes her more exposed.

The family sees her as a potential threat to inheritance, and her newborn becomes another object inside their security choreography. The nursery suite, the portraits, the staff who whisk Becca away—these details show how even care for a child is managed by a hierarchy Maya didn’t design.

Her protective instincts push her toward investigation, but they also keep her grounded. She is not solving the mystery to win status; she is trying to keep her child from growing up inside a machine that destroys women. In parallel, Arianna/Jessica and Caro reveal another face of distorted motherhood. Helen and Mikey create a fake heiress out of maternal ambition mixed with greed, proving that the idea of “protecting the family line” can become monstrous. Caro, the real Arianna, embodies a different form of caretaking: she risks her life to save Jessica from the same system that stole her own childhood.

The story sets up a contrast between motherhood as possession and motherhood as protection. By the end, Maya’s agency is inseparable from Becca’s future. She rejects Marcus not only because of betrayal but because she refuses to model dependency and humiliation for her daughter. The hidden drives behind new family portraits represent a mother’s long game: ensuring leverage exists if Becca is ever threatened. Motherhood here is not passive nurturance. It is strategy, boundary-setting, and the refusal to let a child inherit silence.

Through Maya and Caro, A Girl Like Us argues that female agency often sharpens after birth, because the stakes expand from self-preservation to the protection of someone who cannot yet protect themselves.

Truth, Media, and the Power of Recorded Evidence

This story lives in a world where reality is constantly edited—by television producers, tabloids, lawyers, and family councils. Maya’s fame began on a show built from selective footage and crafted conflict, teaching her early that “truth” can be manufactured.

The paparazzi in her dream and the magazines in Silver House prove that media doesn’t simply observe; it accuses, fixes identities in place, and amplifies shame. The Sterlings understand this perfectly, which is why their first responses to a murder are PR management, legal containment, and controlled silence. They are less afraid of guilt than of headlines. Against that, the novel positions recording as an act of resistance.

Arianna/Jessica’s tapes, the Fisher-Price recorder, the hidden cassettes in shoeboxes, and even the journals at Portas Brancas are all attempts to anchor reality against erasure. Written or taped truth becomes a lifeline for characters who know their voices will be dismissed in live conversation. The irony is sharp: a child’s toy holds the most dangerous confession in the family’s history.

That choice underlines how truth often survives in small, overlooked places while official channels work to bury it. Maya’s skill set as a former reality star becomes unexpectedly valuable here. She understands audience dynamics, the fear of exposure, and how a narrative can be flipped when evidence surfaces. Her final “ace” is not physical power or money; it is control over what can be revealed and when. At the same time, the novel is not naive about media’s morality. Maya knows the same public that might help her also once tore her apart.

Truth in this book is not automatically liberating; it is a tool that can save or destroy depending on timing and framing. Still, the existence of a recorded confession shifts the balance. It creates a fact immune to family spin, and it gives Maya a way to negotiate survival without begging for belief.

A Girl Like Us keeps returning to this idea: when institutions are built on denial, keeping proof is an act of courage, and choosing how to release it is the last space where the powerless can gain power.