Isaac’s Song Summary, Characters and Themes

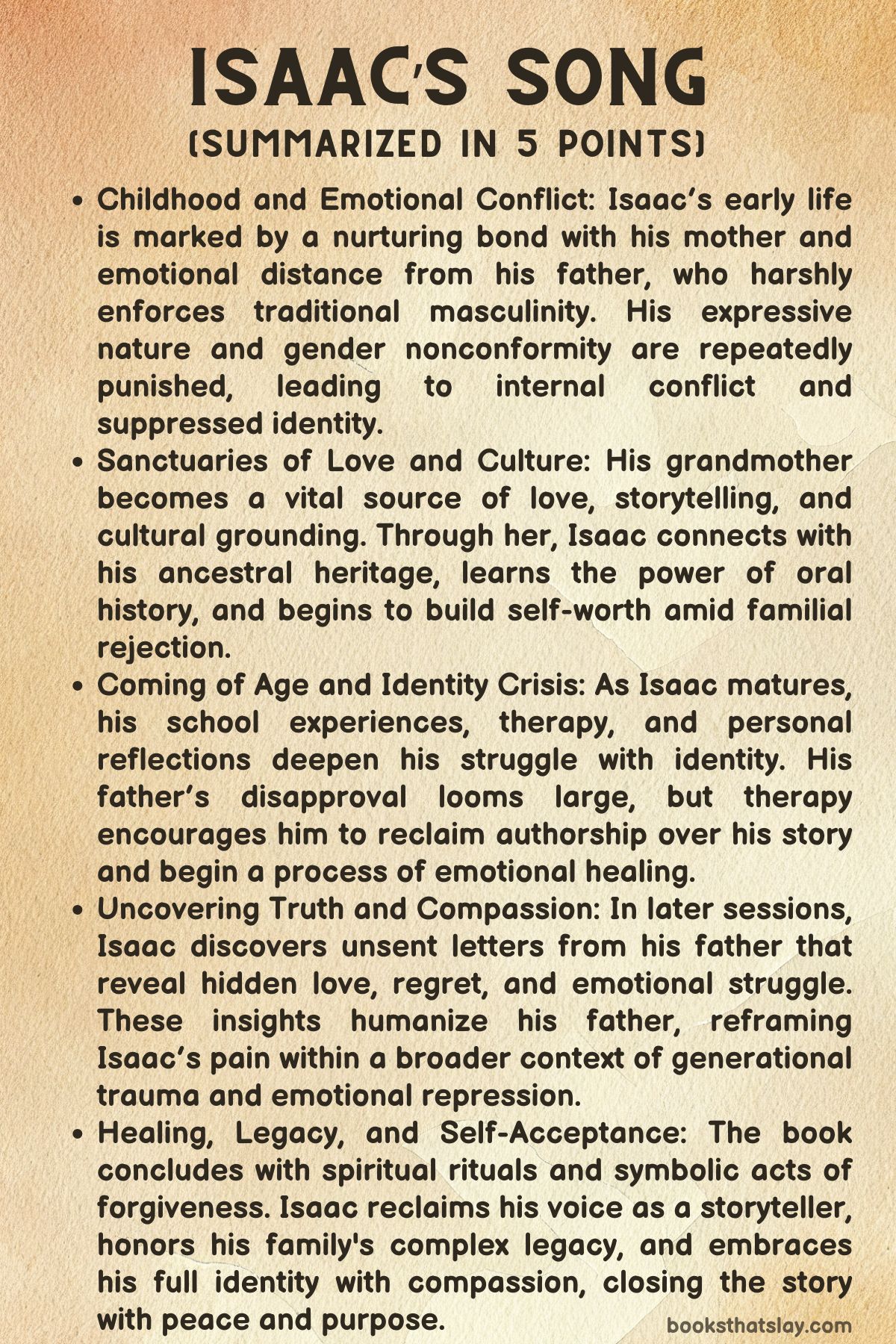

Isaac’s Song by Daniel Black is a moving memoir that traces the life of Isaac Swinton, a young Black man navigating the turbulent intersections of race, sexuality, masculinity, and family expectations. Set within the backdrop of Black working-class America, the story unfolds through confessional storytelling and therapeutic introspection.

It is not only a recounting of events but a spiritual and emotional journey toward self-acceptance, love, and healing. From early childhood through adulthood, Isaac wrestles with deeply rooted pain, parental rejection, and societal constraints, ultimately discovering power in truth, storytelling, and the inherited resilience of his ancestors.

Summary

Isaac Swinton’s story begins in sorrow, with the unexpected death of his estranged father. Though their relationship was distant and strained, Isaac finds himself overtaken by grief.

Red cardinals perched outside his window on the day of his father’s death stir a sense of symbolic significance, suggesting a spiritual reckoning he cannot ignore. At the funeral, Isaac is overwhelmed by the presence of people who seemed to have known and cared for his father in ways he never did, deepening his emotional confusion and sparking a journey of internal excavation.

Seeking answers, Isaac begins therapy. His therapist refuses to let him lean into blame or victimhood.

She tells him that healing is his responsibility—not his father’s, not society’s. Through metaphors and challenges, she dismantles his beliefs that an apology or external validation will fix his pain.

Instead, she helps him see that healing is a self-chosen path, and that writing his story might become the most powerful tool in reclaiming himself.

As he begins to narrate his life, Isaac reflects on his childhood. His mother, vibrant and creative, gives him love, music, and stories.

She creates a magical world for him through an imagined performance called “Isaac’s Song,” helping shape his identity and artistic inclinations. Though she disciplines with firmness, she always tempers it with warmth.

His father, in contrast, is stern and emotionally distant, defining masculinity through physical toughness and labor. He struggles to connect with Isaac, particularly because of Isaac’s gentle, artistic, and expressive personality.

Though their relationship is riddled with tension and hurt, Isaac recalls moments that reveal his father’s complex care—like hauling a massive Christmas tree for his school or gifting him a red tricycle. These actions, devoid of verbal affection, are signs of love expressed through sacrifice.

However, his father’s discomfort with Isaac’s femininity causes lasting damage. A heartbreaking moment comes when Isaac, dressed in his mother’s clothes and makeup, is violently rejected by his father.

The incident marks a rupture in their already fragile bond.

Grandma’s home becomes a haven for Isaac. She bathes him in generational wisdom and unshakable love.

Her storytelling helps him understand his ancestral lineage—one filled with survival, faith, and dignity. She validates Isaac’s uniqueness and instills in him the idea that he has the right to exist and be loved exactly as he is.

Her presence in his life softens some of the harshness he endures at home and reinforces his sense of self-worth.

In therapy, Isaac continues to wrestle with his identity and his past. He confronts his suppressed sexuality, recalling the shame and silence he lived with.

A conversation with a classmate triggers a confession that he is gay. When he shares this truth with his mother, her reaction—denial and violence—shatters the idealized image he had of her.

He realizes he has simplified both parents into rigid roles: the villainous father and the loving mother. But therapy teaches him that both are flawed, complex people who loved him in different, imperfect ways.

His father’s stories about their family roots in Arkansas provide deeper historical context. Isaac learns about relatives like Isadore, a conjurer whose family was destroyed by racial terror.

These ancestral memories give Isaac a richer understanding of his father’s hardness—a survival tactic passed down through generations. The violence, silence, and discipline Isaac grew up with were shaped by histories of loss and fear.

Understanding this doesn’t excuse the pain but reframes it.

Isaac tries to conform to societal expectations by pursuing relationships with girls, but these encounters only emphasize his disconnection from that version of himself. His relationship with Marie, a closeted queer teen, provides companionship, but when she leaves him for another girl, he is forced to confront the masks they both wore.

His attempts at heterosexual intimacy are hollow, and he starts to recognize that he has been performing a version of himself that others expect rather than who he truly is.

A particularly charged moment occurs during a debate with his father over religion. Prompted by Marie’s questions, Isaac challenges the Bible’s authorship, leading to a violent clash.

But for Isaac, this confrontation signals a deeper shift. He is no longer afraid—not of God, not of his father.

He has begun to claim his own spiritual and intellectual independence.

College becomes a sanctuary. At Lincoln University, an HBCU, Isaac finds intellectual freedom, creative validation, and cultural pride.

He immerses himself in the works of James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, and Zora Neale Hurston, whose writing helps him redefine Blackness, masculinity, and love. His friendship with Adam, a reserved and wise classmate, deepens his emotional maturity.

Adam’s eventual death from AIDS leaves a lasting impact, representing both the fragility of queer life and the strength of true connection.

Professional life presents its own challenges. At Microsoft, Isaac confronts microaggressions and subtle racism.

In one humiliating incident, he and a colleague are asked to perform for white co-workers’ amusement. The trauma of that moment mirrors earlier experiences of feeling unseen and devalued.

Conversations with his parents after this experience reveal the enduring struggle of Black people in America—how survival often demands swallowing pain. His therapist encourages him to choose battles that serve his growth, not merely react to injustice.

After his father’s death, Isaac returns home and discovers a box of unsent letters written by his father. These letters—raw, reflective, and filled with regret—reveal a man trying to apologize, to explain, and to love in the only way he knew how.

They show his father’s torment over his own failures, his fear of not being man enough, and his ultimate pride in Isaac’s courage. The inheritance of their family land becomes both literal and symbolic: a passing down of identity, responsibility, and hope.

Parallel to this emotional reckoning, Isaac writes a novel about two enslaved brothers, Matthew and Jesse Lee. Torn apart by slavery but spiritually linked, their story mirrors Isaac’s own relationship with his father and uncle.

Over time, he realizes that Matthew is based on his Uncle Esau, and Jesse Lee on his father. The novel becomes more than fiction—it is a healing act of remembering and reclaiming.

In the end, Isaac performs a ritual at his father’s grave, offering libation and speaking his truth. He releases his pain, acknowledges his father’s love, and forgives him.

Through storytelling, Isaac finds clarity. His memoir becomes what he calls a “black male ballad”—a tribute to vulnerability, legacy, and redemption.

He finally understands that healing doesn’t come from erasing the past but from giving voice to its truths. Through this act, he not only finds freedom for himself but also honors the generations who came before him.

Key People

Isaac Swinton

Isaac Swinton, the central figure of Isaacs Song, emerges as a deeply sensitive, artistic, and intellectually curious young Black man navigating a tumultuous emotional and cultural landscape. From the outset, Isaac is portrayed as someone profoundly affected by both external rejection and internal conflict.

His emotional journey begins with grief at his estranged father’s funeral, which unearths a reservoir of unresolved pain. Isaac’s complexity lies in his duality—he is both fragile and resilient, burdened by the emotional violence of familial expectations and societal homophobia, yet propelled forward by his yearning for self-understanding.

His therapy sessions reveal a young man unlearning a narrative of victimhood and reconstructing a new identity centered on agency, creativity, and truth-telling.

Isaac’s creative pursuits—music, literature, painting, and especially dance—serve not only as forms of expression but as vehicles of survival. They allow him to claim space in a world that often seeks to erase queer Black voices.

Yet this self-expression often clashes with his father’s expectations, leading to emotional and physical trauma that becomes central to Isaac’s emotional reckoning. His relationship with his sexuality is particularly fraught; he grapples with shame, performative heterosexuality, and internalized fear until he arrives at a hard-won acceptance of his queerness.

His intellectual journey, spurred by figures like James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, reorients his understanding of Blackness and offers him cultural anchors. Ultimately, Isaac becomes a vessel for ancestral memory and a literary griot, telling his own story and that of his people.

Through this process, he transforms his pain into purpose, reclaiming his legacy through the act of writing.

Jacob Swinton (Isaac’s Father)

Jacob Swinton is portrayed as both tyrannical and tragically human—a father whose rigid adherence to traditional masculinity and religious conservatism inflicts deep wounds on his son. His emotional repression manifests as authoritarian parenting, and his love is communicated through provision, labor, and unspoken sacrifice rather than affection or praise.

Jacob’s inability to accept Isaac’s queerness and artistic identity leads to cruel incidents of discipline and rejection, including a harrowing episode where Isaac is beaten for expressing femininity. Despite this harshness, the memoir later reveals a more nuanced portrait of Jacob.

The discovery of his unsent letters after his death offers a deeply affecting view into his emotional world. These letters speak of regret, confusion, and a longing to connect, showing that his cruelty was, in part, a symptom of his own unresolved trauma and social conditioning.

Jacob’s character is not redeemed in a simplistic way, but rather recontextualized. Isaac’s growing understanding of generational pain—how Jacob’s behavior was shaped by racial oppression, inherited grief, and toxic patriarchal norms—allows space for empathy without absolution.

Their relationship evolves posthumously, as Isaac reads Jacob’s private writings and sees, perhaps for the first time, a father capable of love and vulnerability. The symbolic passing of family land to Isaac underscores Jacob’s final gesture of acceptance and reconciliation, albeit one he could not fully articulate in life.

Jacob becomes a symbol of both harm and heritage, a paradox that Isaac must hold in order to move forward.

Isaac’s Mother

Isaac’s mother is a figure of warmth, storytelling, and contradiction. Early in his life, she is a nurturing presence who cultivates his imagination through songs, stories, and rituals that create a sense of safety and wonder.

She fosters his creative instincts and self-worth while also instilling a strong sense of discipline and order. Her early encouragement of Isaac’s sensitivity contrasts with the coldness he experiences from his father, making her appear, at first, as a haven of unconditional love.

However, this idealization begins to fracture as Isaac matures. A key moment of rupture occurs when he comes out to her and is met not with compassion, but with denial and physical aggression.

This betrayal shatters Isaac’s image of her as wholly benevolent and forces him to confront the mythologies he has created about his parents.

Her own struggles with alcoholism add further complexity to her character. Her drinking marks the symbolic end of Isaac’s childhood, introducing instability and fear into a relationship he once held sacred.

Despite these flaws, she is also a source of generational wisdom, especially when speaking on issues of race, survival, and spiritual endurance. Over time, Isaac comes to see her as a multifaceted person—someone shaped by her own pain, limitations, and cultural pressures.

Her evolution from idealized protector to complicated human being is part of Isaac’s broader journey toward emotional honesty and self-compassion.

Grandma

Grandma is perhaps the most consistent source of unconditional love and cultural grounding in Isaac’s life. Her home serves as a sanctuary, both physically and emotionally, where Isaac feels safe to explore his identity and hear stories that root him in a broader Black historical consciousness.

She functions as a keeper of memory and a bridge between generations, passing down tales of resilience, dignity, and spiritual strength. Her affirmations of Isaac’s worth counterbalance the shame and rejection he experiences elsewhere, and her presence is imbued with a kind of sacred authority.

Grandma’s role is not just emotional but symbolic. She represents the matriarchal wisdom and spiritual strength that have sustained Black communities across time.

Her belief in Isaac’s uniqueness and her encouragement of his authenticity become essential tools in his process of self-definition. Through her, Isaac gains a language of survival that is both ancestral and personal.

Her influence lingers throughout his life, acting as a moral and spiritual compass long after specific events have passed. She helps him to frame his pain not as a private defect but as part of a larger, intergenerational struggle for truth and self-love.

Ricky

Ricky is a pivotal figure in Isaac’s journey toward sexual identity and self-acceptance. Charismatic, open, and confidently queer, Ricky embodies the kind of self-possession that Isaac both admires and fears.

Their relationship is tender and revelatory—Ricky listens, affirms, and holds space for Isaac’s emerging truths in ways no one else does. He becomes Isaac’s first romantic and sexual partner, and their time together is not just emotionally affirming but also spiritually liberating.

Through Ricky, Isaac experiences what it means to be seen and desired without condition or shame.

Ricky’s confident queerness challenges Isaac to stop seeking validation from others and to embrace his own identity as enough. Though their relationship is brief, it leaves a deep impression, becoming a touchstone for what genuine love and acceptance could look like.

Ricky’s emotional availability, lack of judgment, and affirmation of Isaac’s beauty and brilliance stand in stark contrast to the rejection Isaac has faced from his family. His departure marks the end of a tender chapter, but his impact remains as a catalyst for Isaac’s ongoing evolution.

Adam

Adam, Isaac’s friend from college, serves as an intellectual and emotional mirror, reflecting both the beauty and tragedy of queer Black life. Quiet, brilliant, and introspective, Adam is a kindred spirit whose dignity and insight offer Isaac a new model of manhood.

Their relationship is platonic but profound—a meeting of minds and souls that transcends physical intimacy. Adam’s presence at Lincoln University, an HBCU where Isaac begins to find cultural belonging and academic stimulation, enriches Isaac’s understanding of love, vulnerability, and mortality.

Adam’s eventual death from AIDS is a devastating loss that underscores the precarity of queer life, particularly for Black men. Yet even in death, Adam’s memory becomes a spiritual guidepost.

He teaches Isaac about the sanctity of intellectual pursuit, the quiet strength of self-possession, and the power of being fully oneself. Adam’s character encapsulates the intersection of brilliance and fragility, leaving behind a legacy of courage and emotional honesty that Isaac carries forward.

Marie

Marie is a fellow closeted queer teen whose relationship with Isaac highlights the complexities of performative heterosexuality and the desperate search for belonging. Their connection is built on mutual understanding and emotional intimacy, but it is never truly romantic.

Instead, it functions as a protective façade for both of them in a society hostile to queerness. Marie’s eventual decision to pursue a relationship with another girl forces Isaac to confront the illusion they both sustained—that proximity to heterosexual norms could offer safety or fulfillment.

Marie’s significance lies in what she reveals about Isaac’s internalized shame and longing for approval. Her companionship offers temporary solace, but also reinforces the disconnect between who Isaac is and who he’s pretending to be.

Their shared experience reflects the broader pressures faced by queer youth, especially within communities steeped in religious and cultural conservatism. Marie’s departure is painful but necessary—it pushes Isaac to stop hiding and start living authentically.

Matthew and Jesse Lee

Though fictional, Matthew and Jesse Lee—the protagonists of Isaac’s novel—are deeply symbolic avatars for Isaac’s own familial lineage. These two enslaved brothers represent fractured love, ancestral trauma, and the enduring hope of reunion.

Matthew’s relentless search for Jesse Lee mirrors Isaac’s emotional quest for connection with his father, while Jesse Lee’s suffering and resilience echo the buried wounds of Black manhood and generational pain.

As the novel progresses, Isaac realizes that Matthew and Jesse Lee are not just characters but reflections of his own family: Uncle Esau and his father Jacob. Writing their story allows Isaac to reinterpret his lineage, not as a chain of failures and silence, but as a tapestry of survival and love.

Through these characters, Isaac accesses a mythic dimension of truth, where storytelling becomes both reclamation and ritual. They are the soul of the “black male ballad” that Isaac ultimately writes—songs of grief, resistance, and hope passed down through generations.

Themes

Familial Legacy and Generational Trauma

In Isaac’s Song, the emotional heart of Isaac’s journey lies in confronting the legacy of his father and the generational trauma woven into their lineage. Isaac’s father, Jacob, is initially a figure of alienation—an authoritarian presence whose rigid expectations and emotional distance inflict lasting wounds.

Yet, as Isaac reads Jacob’s unsent letters and learns more about his father’s life, a profound transformation occurs. The letters become an intimate portal into Jacob’s soul, revealing vulnerabilities, regrets, and a desire for connection that had always been obscured by discipline and silence.

This revelation compels Isaac to reassess the inherited emotional patterns in his family. The narrative presents a powerful portrait of how unspoken trauma—rooted in Jacob’s own childhood losses and societal pressures—manifests in controlling behavior and detachment, particularly toward a son who challenges his vision of masculinity.

The discovery of ancestral stories, including those of cousin Isadore and the fictionalized enslaved brothers, further expands Isaac’s understanding of his family’s endurance and suffering under systemic oppression. These stories are not just history—they are emotional blueprints that explain, though never justify, the silence, rage, and fear that shaped his father’s parenting.

Isaac’s act of storytelling becomes his means of interrupting this cycle, choosing compassion, complexity, and voice over suppression and anger. Through this intergenerational lens, the memoir underscores the importance of acknowledging and understanding family history—not just to forgive, but to avoid replicating it.

Masculinity and Identity

The tension between societal constructs of masculinity and Isaac’s emerging identity as an artistic and queer boy is one of the most powerful and recurring elements in the memoir. His father embodies a traditional ideal of manhood—stoic, physically laborious, emotionally restrained—and expects Isaac to conform.

Isaac’s expressive nature, love for music, dance, and eventually literature, are perceived as deviations rather than strengths. This dissonance is particularly painful because it is laced with both love and violence; moments of paternal pride are often followed by acts of rejection.

One of the most heartbreaking episodes occurs when Isaac dresses in his mother’s clothes, hoping to be seen and loved, but instead meets brutality. These incidents define how Black boys are often policed into narrow definitions of masculinity, where vulnerability, creativity, and non-conformity are punished.

As Isaac matures, he starts to question these paradigms, especially through the intellectual space offered by college and therapy. His deepening relationship with literature, his connection with other queer individuals, and his conversations with his father later in life all contribute to a reframing of what it means to be a man.

He begins to see masculinity not as a rigid set of behaviors, but as a space where tenderness, introspection, and authenticity are possible. By embracing this redefinition, Isaac not only liberates himself from the constraints of inherited gender roles but also begins to reimagine his father’s actions as the product of fear rather than hatred.

The Search for Self and the Power of Expression

Throughout Isaac’s Song, the act of self-expression emerges as Isaac’s most vital lifeline. Whether it’s music, storytelling, painting, or dance, each creative outlet allows him to name, understand, and survive his internal chaos.

His art is not merely a hobby or talent—it is a form of testimony and resistance against forces that seek to define him externally. In a world where he is constantly misunderstood or silenced—by his family, by school systems, by religion, and by the corporate world—his voice becomes his refuge.

Therapy challenges him to take ownership of his healing, not by waiting for apologies or external validation, but by choosing how he wants to narrate his own pain and growth. Writing, particularly the fictional story of Matthew and Jesse Lee, becomes the mechanism through which Isaac confronts his own emotional past.

The fictional narrative is a metaphorical mirror, reflecting his familial wounds and his longing for reunion and reconciliation. Through the process of creating this narrative, Isaac learns that storytelling is not about escape—it is about survival and reconstruction.

It allows him to say the unsaid, mourn what was lost, and imagine what healing might look like. His journey shows that voice and agency are not handed to us—they are chosen, nurtured, and fiercely protected.

Expression becomes not just a means of communication, but a reclamation of personhood.

Reconciliation and Forgiveness

Isaac’s evolution is not complete without his movement toward reconciliation—not only with his father but with himself. The road to this point is layered with painful reckonings.

Initially, Isaac sees his father as an oppressor, the embodiment of the rejection and violence he has endured. Yet, through therapy, memory, and eventually the discovery of Jacob’s letters, Isaac comes to understand his father as a wounded man who tried, however imperfectly, to love.

Forgiveness is not presented as a sudden decision but as a slow, deliberate shift in perspective. It is informed by empathy, historical context, and emotional courage.

Isaac recognizes that Jacob’s inability to love openly was not about Isaac’s failings but about Jacob’s own unhealed wounds. This understanding allows Isaac to visit his father’s grave and speak honestly—not from obligation, but from a place of truth.

He acknowledges the damage, honors the effort, and releases his resentment. But reconciliation is not confined to father and son.

Isaac also confronts his idealization of his mother and the emotional betrayal he felt when she rejected his sexuality. Over time, he learns to see her, too, as a full person—capable of love and failure in equal measure.

Forgiveness, then, is less about exoneration and more about liberation. By letting go of his pain’s grip on him, Isaac frees himself to live more fully.

It is not about denying harm but about choosing healing over resentment.

Queerness and Belonging

The memoir presents Isaac’s queerness not just as a personal attribute but as a journey toward belonging in a world structured to exclude him. From early confusion and suppression to eventual pride and clarity, Isaac’s path toward embracing his sexuality is shaped by fear, rejection, curiosity, and eventually, love.

His early attempts at heterosexual relationships are depicted with tenderness and discomfort, showing how societal pressure forces him to perform a role that disconnects him from his truth. The relationship with Marie is especially poignant—a shared hiding place between two queer teenagers, bound not by romance but by mutual secrecy.

When that relationship ends, Isaac is left to face himself without a buffer, which becomes a turning point in his emotional maturation. His eventual romantic experience with Ricky offers something different: affirmation, mutual recognition, and the realization that love does not have to be shameful.

Yet even that moment is fleeting. It is in the enduring friendship with Adam, and the literature of Baldwin and Morrison, that Isaac finds a more lasting sense of queer belonging.

These connections provide spiritual and intellectual companionship that validates his existence. What makes Isaac’s queerness radical is not just that he is gay, but that he refuses to suppress it for comfort or conformity.

His refusal to compartmentalize his identity—and instead integrate it into his art, relationships, and spirituality—marks his growth. Queerness becomes not a secret to hide, but a truth to live and love through.

Spiritual Conflict and Rebirth

Isaac’s spiritual evolution is deeply influenced by his father’s rigid religiosity and the oppressive narratives he associates with it. Raised in a context where faith is presented as fixed doctrine and obedience, Isaac initially struggles to reconcile his queerness and curiosity with the image of God that condemns both.

This results in feelings of unworthiness, internalized guilt, and a rejection of divine intimacy. His theological questioning, sparked by conversations with Marie and later encounters with Black literature, challenges this inherited view.

When he confronts his father about the Bible’s authorship and is met with violence, the moment becomes symbolic—it is the breaking point of inherited belief. Isaac walks away from that confrontation not with anger, but with autonomy.

He begins to seek a spiritual path that honors his doubts, desires, and experiences. Over time, spiritual meaning re-emerges not through traditional religion but through symbolism, memory, and creative acts.

Encounters like the fallen baby bird become deeply sacred moments—intimate reminders of a God who is present, not punitive. Spirituality becomes less about fear and more about faith in life’s mysterious coherence.

This redefinition allows Isaac to approach religion not as a closed system, but as a conversation between the divine and the human. His eventual peace is not theological certainty but the freedom to believe on his own terms.

In this way, his spiritual rebirth mirrors his personal transformation: a journey from inherited control to chosen truth.