Finding Grace by Loretta Rothschild Summary, Characters and Themes

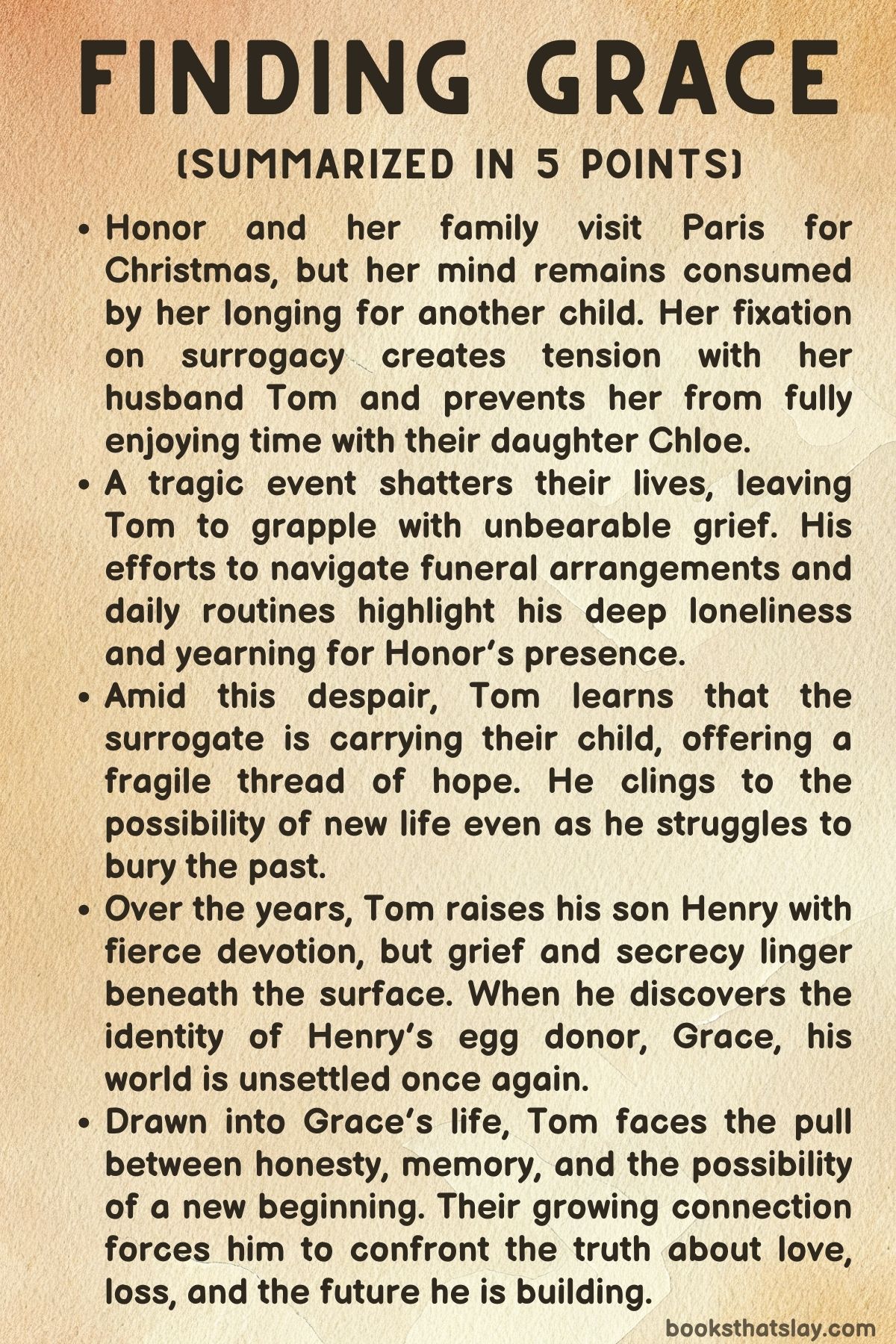

Finding Grace by Loretta Rothschild is a moving exploration of love, grief, and the fragile hope that binds families together. The novel follows Tom and Honor, a couple marked by loss and longing, as they attempt to preserve their marriage while struggling with infertility.

Their journey is torn apart by tragedy when a terrorist attack shatters their family, leaving Tom to navigate an unbearable absence while holding on to the promise of new life through surrogacy. As the years unfold, fate leads him toward Grace, a woman unknowingly tied to his past, forcing him to reconcile love, truth, and the possibility of starting again.

Summary

The novel opens with Honor, her husband Tom, and their daughter Chloe arriving in Paris for their annual Christmas stay at the Ritz. Though Honor adores her family, she is consumed by an obsession with having another child.

After years of miscarriages, surgery, and heartbreak, she has pinned all her hopes on their surrogate, Jess. This fixation creates tension with Tom, who feels neglected and weary of Honor’s relentless pursuit of another baby.

Even in joyful moments with Chloe, Honor cannot quiet her anxiety.

At the Ritz, traditions highlight the cracks in their relationship. Tom begs Honor to focus on the present and appreciate what they have, but she remains unable to let go.

Their quarrels spill into small rituals, and even moments of reconciliation reveal the depth of their strain. The following morning, Honor again slips into thoughts of Jess’s pregnancy, which sparks another argument.

Tom insists he will end their fertility journey if this attempt fails. Though shaken, Honor masks her turmoil to protect Chloe’s happiness.

Later, while photographing Chloe near the grand Christmas tree, Honor notices a pregnant woman nearby. She smiles politely—moments before the woman detonates a suicide bomb.

The explosion kills Honor and Chloe instantly, leaving Tom with unimaginable loss.

Tom wakes in a hospital, broken physically and emotionally. He struggles through the grim practicalities of funerals and bureaucracy while clashing with Honor’s cold mother, Colette, who tries to control arrangements.

With no one to lean on, Tom feels Honor’s absence most painfully in the ordinary tasks she once managed effortlessly. He brings Honor and Chloe’s coffins back to England, burdened with grief but resolved to honor Honor’s wishes.

At the funeral, friends gather to support him, though distance keeps many away. Tom carries Chloe’s tiny coffin, whispering his love, and reads a Baudelaire poem Honor had cherished.

Among the mourners is Jess, the surrogate now carrying Tom’s child, a symbol of life in the shadow of death. Months later, Jess gives birth to Henry, who becomes Tom’s sole reason to survive.

Four years pass. Tom devotes himself to raising Henry, clinging to Honor’s routines and preferences to preserve her presence.

Outwardly, he is a strong single father, but inwardly he is haunted. His isolation deepens until an administrative mistake reveals the identity of Henry’s egg donor: Grace Stone.

When Tom listens to a recording of her voice reciting the same Baudelaire poem that once bound him and Honor, he is shaken. Grace is no longer an anonymous figure—she is real, and unknowingly part of his son’s story.

Curiosity drives Tom to Grace’s wine shop, Sprezzatura, where he sees her for the first time and is startled by her resemblance to Honor. Though he flees in shock, he cannot let go of the connection.

Fate brings them together again when Grace mistakes him for a widower attending her support group. Their conversations stir unexpected feelings, and despite warnings from his friend Annie to abandon this dangerous pursuit, Tom returns, eager to see her.

As Tom and Grace grow closer, their bond deepens into romance. Grace reveals her own grief: her husband Pietro’s death and her decision to donate eggs as a way to create meaning from loss.

She insists Henry is Honor’s child, not hers, unaware of the truth. Tom, torn by guilt, cannot confess that Henry is biologically hers.

Their love blossoms nonetheless, and Grace becomes part of Tom and Henry’s daily life.

Yet cracks appear. Friends notice Grace’s striking resemblance to Honor.

Lauren, Tom’s friend and Honor’s confidante, grows suspicious, and Colette constantly compares Grace to her daughter. Pressure mounts when Lauren, in a drunken slip, reveals that Henry was conceived with an egg donor.

Though she quickly tries to backtrack, Grace begins to sense the depth of Tom’s secrecy.

Tom, Grace, and Henry temporarily escape to Scotland, where they find peace and intimacy. Tom proposes marriage, and Grace accepts, but their return to London brings everything crashing down.

At an engagement party arranged by Lauren, the secret is exposed: a recording of Grace’s donor profile is played aloud, revealing her identity to all. Humiliated and betrayed, Grace leaves Tom, declaring their relationship a lie.

Shattered, Tom struggles to repair his life. Lauren admits to exposing him, driven by her own misguided feelings for him, which severs their friendship.

Meanwhile, Grace removes herself completely, and Tom finally begins the painful process of unpacking Honor and Chloe’s belongings, sharing their stories openly with Henry to preserve their memory.

Six months later, at Christmas, Tom lives more honestly, centering his world on Henry. Unexpectedly, Grace returns with the support of her friends.

She is pregnant with Tom’s child and has come to reconcile, choosing to embrace a future together. With hope renewed, Tom, Grace, and Henry finally begin to build a family—one rooted not in secrecy or grief, but in truth and love.

Characters

Honor

Honor is the emotional core of Finding Grace, defined by her fierce longing for motherhood and her struggle to reconcile love with loss. Though she deeply adores her husband Tom and their daughter Chloe, her overwhelming fixation on having another child consumes her.

Years of miscarriages, surgeries, and the reliance on a surrogate leave her hollowed out, desperate, and often blind to the joys of the family she already has. Her internal world is torn between devotion and obsession—unable to live fully in the present because of her inability to let go of the hope of new life.

Her final moments, shattered by the bombing in Paris, underscore the tragic irony of her story: a woman whose entire existence revolves around nurturing and creation is extinguished just as new life stirs in her absence. Honor represents both the fragility of dreams and the brutal unpredictability of fate.

Tom

Tom is the novel’s anchor, both devastated husband and struggling father, forced into survival after unthinkable loss. At first weary of Honor’s obsession with fertility, he longs for simplicity and contentment with the family they already have.

After losing Honor and Chloe, his grief is rendered in excruciating detail—haunted by memories, burdened by bureaucracy, and ultimately tethered to life only by the fragile thread of Jess’s pregnancy. His devotion to Henry, born from that last chance, becomes almost rigid, as though by replicating Honor’s ways he can preserve her memory.

Yet beneath his strength lies a constant vulnerability, the fear of failing his son, and the guilt of desiring a future with Grace. Tom is a man split between honoring the dead and embracing the living, caught in the painful ambiguity of love after loss.

Chloe

Chloe, though young, is portrayed with vibrancy and innocence that magnifies the weight of her loss. She embodies joy, imagination, and ritual—her button-pressing in the Ritz lift, her fascination with Christmas trees, her playful spinning in the lobby.

To her, life is a wonder, unclouded by her mother’s grief and her father’s weariness. Her death, sudden and brutal, is the cruel theft of pure potential, and it reverberates through Tom’s life as the most unbearable wound.

Even in absence, Chloe remains present—through toys, memories, and the silence she leaves behind. Her presence symbolizes innocence destroyed by violence, and her memory shapes the way Tom parents Henry, torn between preserving her spirit and moving forward.

Jess

Jess, the surrogate, is a quiet but pivotal figure whose body carries Honor and Tom’s last hope. Though she remains largely in the periphery, she represents sacrifice, possibility, and continuity.

Her pregnancy is both salvation and torment—life arriving even as death devastates Tom’s world. Her attendance at the funeral, discreet yet powerful, signals her deep role in Tom’s healing journey, not as a replacement but as a bearer of what remains.

Jess is written less as a full character and more as a symbol of hope and continuity, yet her existence raises profound questions about motherhood, identity, and the boundaries of family.

Colette

Colette, Honor’s mother, is portrayed as cold, controlling, and often selfish. Her clashes with Tom reveal a strained history with Honor, one marked by absence and emotional distance.

She seeks to impose her will even in the aftermath of tragedy, insisting on burial in France and dismissing Tom’s grief. Yet, in later sections, she emerges as a quieter support, particularly with Henry, showing glimpses of depth beneath her rigid exterior.

Colette’s complexity lies in her contradictions—she is both antagonist and caregiver, a reminder that grief magnifies old wounds while also creating unexpected bonds.

Grace Stone

Grace is the hidden thread that ties the novel’s past and present together. An egg donor who never expected to know her biological child, she becomes entwined with Tom and Henry through fate and circumstance.

Grace is not simply a mirror of Honor, though her resemblance and the shared Baudelaire poem create eerie parallels; she is a woman with her own grief, her own losses, and her own yearning for connection. Her relationship with Tom oscillates between authenticity and the shadow of secrecy, ultimately revealing her as both a source of redemption and a figure of painful truth.

Grace’s journey illustrates the fragile boundary between anonymity and intimacy, chance and destiny, as she transitions from a faceless donor to a central figure in Tom’s and Henry’s lives.

Lauren

Lauren serves as both comic relief and a catalyst for conflict. Initially portrayed as somewhat naïve and intrusive, her role deepens as her misguided love for Tom emerges.

Her betrayal—exposing Grace’s donor identity—shatters the delicate balance of Tom’s new life, motivated less by malice than by desperation for recognition. Lauren embodies the dangers of unacknowledged longing and misplaced loyalty.

She is flawed, often insensitive, yet her presence highlights the vulnerabilities of the central characters, especially Tom. In many ways, she is a cautionary figure, reminding the reader of how grief can distort relationships and how love unexpressed can curdle into harm.

Annie and Oliver

Annie and Oliver form the backdrop of friendship and community, grounding Tom when his life collapses. Annie, particularly, functions as his conscience—constantly warning him about the risks of pursuing Grace and trying to tether him to honesty.

Her anger and protectiveness sometimes clash with Tom’s need for secrecy, but her loyalty is unwavering. Oliver, though less central, offers companionship and stability.

Together, they highlight the importance of chosen family, the circle of friends who become a lifeline when tragedy strips away everything else.

Themes

Obsession and Fertility

In Finding Grace, Honor’s fixation on fertility is not just a subplot—it defines her psychological state and strains every relationship around her. Her relentless desire for another child eclipses her ability to cherish what she already has in her daughter Chloe and her marriage with Tom.

Rothschild paints Honor’s yearning with an intensity that borders on self-destruction: checking Tom’s phone for updates from the surrogate, mentally living in a world where the pregnancy defines her worth, and snapping at trivial moments that could otherwise be filled with joy. This obsession is not framed as vanity but as a deep void, one rooted in repeated miscarriages and the trauma of ovarian removal, which makes her pursuit both sympathetic and unsettling.

It highlights the human tendency to measure life’s completeness against what is absent rather than what is present. Fertility becomes a metaphor for control—Honor seeks to bend biology and fate to her will.

Yet her fixation blinds her from appreciating Chloe’s innocence and Tom’s steady devotion, slowly corroding the family dynamic. By the time the terror attack robs her of everything, the irony is unbearable: the very life she longed for exists in Jess’s womb, but she herself is gone.

This theme challenges readers to confront the destructive potential of obsession, even when its roots are love and hope.

Grief and Survival

Grief in Finding Grace is not linear but cyclical, unpredictable, and crushing. After Honor and Chloe’s deaths, Tom’s existence becomes a study in endurance rather than living.

His suffering is heightened by the bureaucracy of loss—choosing coffins, negotiating funeral logistics, and confronting Honor’s cold mother, Colette. These practical burdens become metaphors for the heavy, unyielding nature of grief.

Tom’s survival hinges on fragments of memory—Honor’s diary, Chloe’s toys, the familiar scent of perfume—which simultaneously comfort and torment him. Rothschild shows how grief isolates: Tom’s friends try to help but cannot bridge the gap between his pain and their sympathy.

The paradox arrives when Jess’s pregnancy is confirmed: life continues in the most literal way possible, yet Tom remains consumed by death. The theme underscores survival as less about healing and more about carrying unbearable weight until slivers of meaning emerge.

Grief transforms Tom into a man defined by responsibility, first to Henry and later to Grace, but it never disappears. Instead, it reshapes him, revealing that survival does not erase sorrow—it teaches one how to coexist with it.

Family, Legacy, and Belonging

The novel persistently questions what defines a family. Is it biology, choice, shared history, or the bonds formed through resilience?

Honor insists she is the mother of her surrogate-born child, pushing against societal skepticism. After her death, Tom becomes both father and mother to Henry, attempting to preserve Honor’s influence through routines and rituals.

Later, the arrival of Grace complicates the narrative of belonging. As Henry’s egg donor, she represents both biological truth and emotional disruption.

For Tom, Grace embodies continuity—an uncanny resemblance to Honor and the literal genetic thread tying her to Henry. Yet for Grace, the relationship demands redefining motherhood itself, as she insists Honor remains Henry’s true mother despite biology.

Rothschild thus broadens the idea of family beyond traditional definitions, suggesting it is constructed in layers of love, memory, and responsibility rather than confined to blood. Belonging, in this sense, is earned and chosen, even when it is haunted by loss and secrecy.

The novel’s final reconciliation between Tom, Henry, and Grace underscores that families can be remade, but only through honesty and acceptance.

Love, Betrayal, and Redemption

Love in Finding Grace is portrayed as both a healing force and a potential source of betrayal. Tom’s marriage with Honor is filled with tenderness but also marked by conflict, as her fixation on fertility distances them.

After her death, his love for Henry becomes his anchor, but it is also rigid, almost suffocating, as he tries to preserve Honor’s memory in every detail of daily life. The arrival of Grace presents Tom with a chance at renewal, yet his secrecy about her role as Henry’s biological mother poisons the relationship from within.

When Lauren exposes the truth, Grace’s sense of betrayal is profound—her love for Tom and Henry suddenly feels manipulated, a construct built on withheld truths. Yet redemption lies in confrontation.

By eventually choosing transparency with Henry and facing his grief more openly, Tom begins to rebuild trust. Grace’s return at the end, pregnant with Tom’s child, signifies forgiveness and renewal, not as erasure of betrayal but as an acknowledgment that love can evolve and survive imperfection.

Redemption, then, is not clean or simple—it requires painful truth and the willingness to begin again.

Fate, Chance, and the Fragility of Life

From the devastating randomness of the suicide bombing to the mistaken disclosure of Grace’s identity, chance events govern the trajectory of Finding Grace. Life and death hinge on arbitrary moments: Honor’s fixation is rendered meaningless by sudden catastrophe, and Tom’s attempt at order is undone by a misplaced letter and a CD.

Rothschild emphasizes the fragility of existence, where grand plans collapse under the weight of accidents and unforeseen forces. Yet chance also offers unexpected grace—Henry’s birth, Grace’s resemblance to Honor, the serendipitous reappearance of love.

Fate in the novel is neither benevolent nor cruel but indifferent, scattering loss and possibility alike. The theme reminds readers that control is an illusion; what matters is how characters respond to what they cannot foresee.

Tom’s eventual acceptance of uncertainty—choosing to embrace Grace and a new child despite fear of repetition—demonstrates resilience. The fragility of life, instead of rendering existence meaningless, becomes the very reason to cherish fleeting connections.