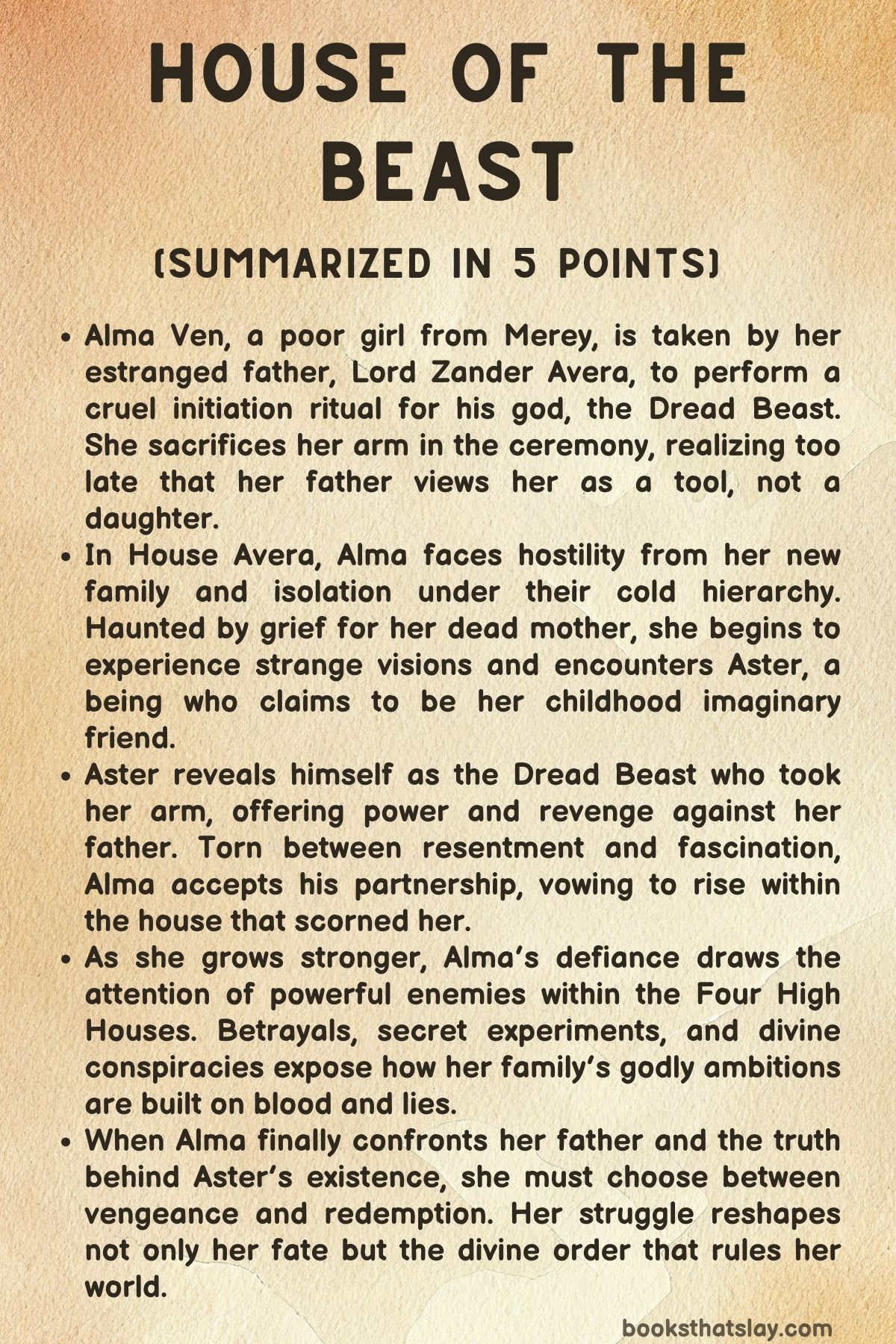

House of the Beast Summary, Characters and Themes

House of the Beast by Michelle Wong is a dark fantasy novel that follows Alma Ven, a girl born into poverty who discovers that her blood ties her to one of the most powerful and corrupted noble houses in the empire of Kugara. When she is claimed by her estranged father and forced into a brutal ritual, Alma’s life becomes entangled with divine powers, political ambition, and a monstrous god known as the Dread Beast.

As she grows into her inheritance, Alma must confront her father’s cruelty, the deceit of the gods, and her own connection to a being that blurs the line between love and destruction.

Summary

Alma Ven, a young girl from the slums of Merey, lives with her mother Ira, a woman scorned by their neighbors for refusing to worship the gods. Alma’s world changes when her mother falls ill and cannot afford healing.

Searching for help, Alma uncovers a letter revealing that her absent father, Zander Avera, is a nobleman of House Avera—one of the Four High Houses serving Kugara’s elder gods. In desperation, she writes to him.

Zander arrives, promising to heal Ira if Alma agrees to come with him. Despite her mother’s pleas not to trust him, Alma accepts the bargain to save her life.

Zander takes Alma to his mountainous estate, where he reveals the dark faith of his house: devotion to the Dread Beast, a monstrous god. He subjects Alma to an initiation ritual, severing her arm as an offering.

Before she faints, she glimpses the Beast—a shadowy being who smiles at her as her blood drains into the altar. When she awakens, her arm is gone, replaced with pain and strange visions.

Zander forces her to adopt his name and accept her place as his heir, though his household despises her. His wife Euphina and sister-in-law Darantha view her as a stain on their bloodline.

The family patriarch, the Antecedent, tolerates her only because she might serve the Beast’s will.

Isolated and grieving, Alma is instructed by a patient tutor, Master Vuong, and meets her cousin Kaim, who taunts her for her illegitimacy. The only kindness she receives comes from Fion, Kaim’s aide, who treats her with quiet compassion.

Despite her suffering, Alma clings to hope that her mother will recover. But after she attempts to escape the estate, she accidentally kills a guard using an unknown force.

Zander reveals that her mother has died and condemns her as cursed. The loss breaks her spirit.

Alone in her room, she begins to hallucinate shadows and voices.

One night, her childhood imaginary friend, Aster, appears before her—a silver-haired boy who seems both real and divine. He reveals that he is the Dread Beast, the god who accepted her sacrifice.

He confesses to killing the guard because she wished for it and tempts her to embrace his power. Grieving and furious, Alma accepts his companionship, forming a dangerous bond with the god.

Aster calls it friendship, but it is also possession. When Zander presents her with a new mechanical arm forged from black metal, she moves it perfectly—proof that Aster’s strength now flows through her.

Years later, Alma’s training brings her deeper into the politics of the Houses. Her uncle Maximus, the First Hand of the Beast, interrupts a sacred ritual and tests her in combat.

Though wounded and overpowered, Alma calls upon Aster’s power and defeats him. Before dying, Maximus names her his successor, shocking the court.

Her father rejects the claim, and Alma becomes both a rival and a threat to him. The Houses prepare for the divine Pilgrimage, a journey into the umbral plane where chosen vessels of the gods compete for supremacy.

Alma is taken under the protection of Sevelie, her cousin Kaim’s fiancée, who shows her genuine warmth. But danger follows.

When Alma investigates the ruins of an old medical school—once her mother’s only hope—she is captured by Olissa Goldmercy, a high priestess of another house. Olissa attempts to break her will through torture, but with Aster’s help, Alma unleashes her divine power, killing Olissa and her followers.

Amid the carnage, she spares a small mechanical boy named Six, who seems to resemble her dead half-brother Ephrem. Defying Aster’s urging to destroy him, she decides to protect the boy.

Returning bloodstained to Sevelie’s home, Alma confronts the growing realization that her father orchestrated Olissa’s attack. The betrayal deepens her resolve to confront him.

During the Pilgrimage, she faces Zander in the divine realm, where he reveals his true goal: to overthrow the gods themselves. Zander intends to murder the Weeping Lady, an elder goddess, and claim her divine power to ascend beyond mortality.

Alma also learns that Aster, her constant companion, is not simply a god but the spirit of a long-slain divine child whose essence was stolen by the gods to create their world. When Zander’s ritual awakened that spirit, it was Alma’s soul that the creature clung to, shaping itself into the form of the imaginary friend she once imagined.

Haunted by this revelation, Alma witnesses her father kill the Weeping Lady and steal her sacred eye—the core of divine power. Aster materializes fully, independent of her body, regaining his lost might.

He destroys Zander in retribution, ending his father’s tyranny but unleashing chaos upon the mortal world. Sorrowsend, the capital, begins to crumble as the umbral plane merges with reality.

Aster, now a god reborn, declares vengeance upon all humanity for their centuries of exploitation. Alma begs him to stop, but he refuses.

When he threatens her remaining loved ones, she challenges him, forcing a final confrontation.

Their battle devastates the city. Aster fights with sorrow rather than hatred, unwilling to kill her even as his power shatters the heavens.

Realizing he will not stop unless she ends him, Alma sacrifices herself in turn—allowing him to impale her so she can strike him through the heart. The two fall together, their blood mingling.

Before fading, Aster forgives her, confessing that he loved her and always knew their bond would destroy them both.

In the aftermath, the gods fall silent. Miracles vanish, and the world begins to rebuild without divine rule.

Alma survives her wounds, aided by Sevelie and the construct boy Six. She refuses fame or leadership, choosing instead to return home to Merey.

The city she leaves behind is scarred but free. As Alma walks toward her mother’s grave, she carries both the memory of those she loved and the remnants of Aster’s power within her.

Though the gods are gone, she feels a quiet strength and a sense of peace she has never known. For the first time, she believes that she can live her own life—neither vessel nor victim, but wholly herself.

Characters

Alma Ven

Alma is the furious heart of House of the Beast, a slum-born girl whose longing for belonging and love is twisted into a weapon by people and powers far older than her grief. Severed from her arm and her past in a single ritual stroke, she begins as a daughter willing to sacrifice herself to save her mother, then hardens into a strategist who learns to speak the language of power—obedience, spectacle, and restraint—while holding a private pact with the very god her house venerates.

Her violence is not innate savagery but a survival grammar taught by ostracism, paternal coercion, and divine grooming; whenever she lashes out, the story forces her to confront whether the will behind the blow is hers or the Beast’s. The revelation that her childhood “imaginary friend” was the god who latched onto her soul reframes her arc from possession to negotiation: Alma is neither pure victim nor pure conqueror, but a young woman insisting on moral authorship inside an unequal bond.

By the end, she wages a tragic, lucid rebellion against both patriarch and patron, choosing costly agency over inherited destiny and carrying forward a tempered strength that hints at healing without erasing the scars that gave it shape.

Zander Avera

Zander is patriarchy in ceremonial black: outwardly disciplined, privately ravenous. He treats kinship as currency, reshaping Alma into a political instrument while performing the piety of a vessel of the Dread Beast.

His cruelty is meticulous rather than chaotic—he isolates, shames, withholds, and bargains, all in service of ascent within House Avera’s hierarchy. The revelation that he sacrificed his son Ephrem and would mutilate his daughter under the banner of holiness exposes his theology as ambition dressed in ritual.

Even when confronted in the divine realm, he reframes Alma’s pain as her moral failure, a final act of control that collapses only when the god he serves refuses him. Zander’s death by his own turned blade is poetic justice: a man who tried to claim divinity is destroyed by the reflected edge of his coercion.

Aster

Aster is seduction given the shape of solace, the murdered god-child who grows into a cosmos of grievance and need. He first appears as tenderness—an echo of a lonely girl’s wish—then unfolds as a being older than empires, at once protector, lover, captor, and weapon.

His power magnifies Alma’s will, but his longing to be chosen corrodes the consent he craves; he edits truths, engineers tests, and delights in carnage while insisting it is all for her safety. The origin vision reframes all miracles as theft from his broken body, casting him as both foundation and indictment of Kugara’s sacred order.

When he regains his eye and steps free, his vengeance is operatic, yet he still pulls his deadliest blows against Alma, revealing that for him love and annihilation are neighboring rooms. Their final duel is an ethical crucible: Alma proves love by stopping him; Aster proves love by accepting the end she chooses.

He exits as tragedy incarnate—more wronged than monstrous, and still too dangerous to live.

Ira Ven

Ira is the quiet defiance that raises a daughter outside sanctioned worship and pays for it with isolation. Her tenderness does not erase her severity; she disciplines Alma’s rage because she knows the world will weaponize it.

The hidden letter and the refusal to speak of Zander show a woman trying to quarantine corruption from her child, and the plan to seek modern medicine over divine favor marks her as an ethical counterpoint to Kugara’s theocracy. Her death is the wound the plot keeps pressing, but her posthumous letter—delivered through Ephrem’s spirit—becomes the moral spine of Alma’s recovery, turning grief from a sinkhole into a compass.

Maximus Avera

Maximus, the First Hand, is a study in brutal clarity. His midnight interruption and lethal “test” strip courtly religion to its essence: worth is proven in blood, not lineage.

He is terrifying because he is honest about the order’s values, and his dying nomination of Alma as successor is both recognition and provocation. Whether motivated by admiration, gambit, or madness, he names her what the house most fears she could be, forcing the family to reveal its hypocrisy as it scrambles to invalidate a trial by the very god it claims to serve.

Kaim Avera

Kaim embodies the heir shaped by entitlement and fear. His contempt for Alma reads as defense against displacement; he knows that merit inside House Avera is a performance sustained by cruelty and sponsorship.

The hints of closeness with Fion and his brittle pride around Sevelie reveal a boy policed by expectations, grasping at superiority to avoid being devoured by the machine he benefits from. He is less a villain than a warning: without a break in the cycle, he will become Zander in a more fashionable coat.

Sevelie

Sevelie is social grace sharpened into courage. Introduced as a noble fiancée with impeccable poise, she chooses personal loyalty over house optics, offering Alma shelter and later risking herself to engineer Alma’s escape.

Her capacity to read a room and to mask alarm with wit is political power of a different kind, and her care after the city’s fall reframes nobility as responsibility rather than pedigree. Sevelie’s steadiness gives the narrative a humane countercurrent in a world obsessed with dominion.

Fion

Fion is quiet competency and understated conscience. As Kaim’s aide, he absorbs heat and redirects conflict, signaling a loyalty to people rather than to titles.

His invitation to Alma to leave Kugara is not romance or rescue fantasy but recognition: he sees the cost of staying inside a collapsing sacred economy and offers an exit that honors her agency. He represents the possibility of ordinary goodness surviving in extraordinary times.

Euphina

Euphina’s scorn gives a face to the house’s obsession with legitimacy. Her hostility is more than jealousy; it is the fury of a woman who has followed every rule of succession only to see power bend around a husband’s secrets and a god’s whims.

She polices Alma to preserve a social order that, in truth, does not protect her either, making her both enforcer and casualty of the patriarchy she upholds.

Lady Darantha

Darantha is court venom, fluent in insinuation and veneer. She despises Zander yet mirrors his tactics, using shame, rumor, and procedural challenge to keep threats at bay.

In contesting Alma’s claim after Maximus’s declaration, she demonstrates how nobles launder fear through legalism. Her presence keeps the rooms dangerous even when swords are sheathed.

Master Vuong

Master Vuong is an ethical candle in a windy hallway. His patience with Alma, insistence on fairness, and effort to mediate Kaim’s posturing show teaching as quiet rebellion.

When the Antecedent removes him, the message is clear: kindness is subversive in a house that needs its heirs hungry, not whole. Still, his lessons linger, furnishing Alma with the language and discipline to think beyond rage.

Olissa

Olissa is benevolence inverted—healing repurposed as domination. Her plan to “temper” Alma by drilling out her will is an allegory of sanctified abuse, the medicalized face of spiritual coercion.

Her death scene, recognizing the depth of Alma’s bond with the god, is both taunt and confession: she sees the truth too late and uses it to wound. Through Olissa, the book indicts the way institutions can anesthetize cruelty by calling it care.

Six

Six is the fragile proof that mercy can survive in the rubble. As a clockwork child linked to Ephrem’s image, he is a living archive of the house’s crimes and a mirror for Alma’s choices.

Sparing him marks a hinge in her arc—power constrained by compassion. In the aftermath, his loyalty is not fealty but trust, a relationship built on protection rather than control, foreshadowing a different kind of family.

Ephrem Avera

Ephrem is the lost brother who becomes a lantern. Bound to Alma since childhood, he embodies the cost of Zander’s ascent and the possibility of absolution without forgetting.

By delivering their mother’s letter and clarifying Aster’s origin, he disarms Alma’s self-hatred and redirects her rage toward truth. He is grief made gentle, guiding Alma out of a story written for her and into one she can author.

Themes

Blood, Legitimacy, and the Cost of Belonging

From the first scene in the temple to Alma’s uneasy recognition as an Avera, House of the Beast keeps pressing on the question of what blood entitles a person to—and what it takes from them. Alma’s slum upbringing marks her as an outsider, yet the moment Zander claims her as his heir she learns that belonging to a great house is not a shelter but an extractive bargain.

Kinship is invoked to compel obedience, not to offer care: a father demands a limb as proof of loyalty, a patriarch “accepts” a granddaughter while ordering her fed alone, and a cousin treats her surname as a stain rather than a bridge. The novel shows lineage as a contract enforced through ritual pain and public performance, with the family’s god serving as both witness and weapon.

Alma’s path exposes how institutions dress violence in inheritance, insisting that legitimacy is earned by suffering on the house’s behalf. Yet her bonds of chosen kin—Sevelie’s friendship, Fion’s quiet respect, even Alma’s protection of the construct child Six—offer a countermeasure to blood’s tyranny.

The climax reframes legacy beyond genealogy: when miracles fail and titles wobble, what remains of family is the willingness to risk for one another without demanding sacrifices first. Alma ultimately refuses to perpetuate the Avera pattern.

She does not claim First Hand as a coronation of blood, but rejects the game altogether, choosing to walk away with those she has defended. In doing so, the book argues that belonging is proven by acts of protection and truth-telling, not by heritage sealed in pain.

Body, Sacrifice, and Ownership

Alma’s body is negotiated, inspected, and modified by others long before she can name what she wants from it. The severed arm is not only a mark of devotion; it is a receipt.

House Avera treats flesh as currency: you pay the Beast, and in return the house gains prestige and leverage. Zander’s polished hand and the Antecedent’s golden prosthesis advertise holiness as hardware, turning sanctity into an aesthetic of metal and scars.

Alma’s prosthetic complicates this economy. When she moves it with effortless precision, the spectacle of control flips—suddenly the instrument answers to her, not to the house that purchased it.

The novel keeps returning to the uneasy edge where empowerment and possession meet. Communion with Aster heightens her strength, but the origin of that power—an entity that once reached into her childhood life without consent—contaminates the gift.

Later revelations about the murdered god-child and the stolen sun-eye widen the question of ownership: entire religions are built on a body that was never theirs to take. By the end, when divine voices fall silent, Alma’s relationship to her body is no longer framed by ritual debt.

She chooses how to use the strength Aster leaves her, not because a creed demands it but because she accepts responsibility for what her hands—metal and flesh—can do. The story insists that true consecration is not sacrifice extracted by fear or lineage; it is agency.

The body becomes a site of ethics once power is chosen rather than coerced, and pain is remembered without allowing it to dictate the future.

Abuse, Ambition, and the Cycle of Control

Zander Avera embodies an authoritarian logic that the novel tracks from the household to the heavens: domination masquerading as destiny. He weaponizes love—“for your mother’s sake”—to force Alma into rituals, isolates her under the pretext of education, and frames his cruelty as discipline necessary for greatness.

The house’s hierarchy rewards such behavior. The Antecedent’s approval depends on usefulness, not care; Kaim’s contempt is tolerated because it maintains the pecking order; church officials collude when obedience promises stability.

Violence becomes a language adults use to script a child’s life, and the child learns to speak it back. Alma’s attack on the guard shows how coercion teaches its subjects to repeat harm, even when they hate it.

Maximus’s trial later demonstrates a different shade of control: a charismatic brutality that calls itself truth-testing. In both cases, Alma is told that survival within the system proves the system’s righteousness.

The narrative refuses that conclusion. Alma’s grief at her mother’s death, her disgust after the laboratory slaughter, and her refusal to be “tempered” into obedience mark the points where she severs the cycle.

The final confrontation with Zander is not just a family reckoning; it is an indictment of a worldview that elevates ambition over care and calls that holiness. Killing him does not magically end the pattern—Aster’s rampage shows how wounded power can reproduce the same logic at cosmic scale—but Alma’s subsequent choice to protect others at cost to herself breaks the link between strength and domination.

Authority, the book suggests, is legitimate only when it safeguards the vulnerable rather than consuming them.

Faith, Institutions, and Stolen Divinity

Religious authority in House of the Beast rests on a buried crime: a god-child murdered so that priests could found an order with his stolen eye. From this revelation the novel works backward, recasting every sanctified object and rite as evidence, not of holiness, but of historical theft laundered into doctrine.

The Church of the Weeping Lady refuses healing to non-worshippers; the Houses dress their violence as service to elder gods; inquisitors prize procedure over truth. These institutions look stable because the miracle engine keeps running, but the engine itself is a body they refuse to acknowledge.

When Zander tears the sunfire eye from the goddess, the pretense collapses. Miracles cease, courts falter, and venerable houses scramble to assert relevance without the power they assumed would never end.

Yet the book rejects a simple turn from belief to nihilism. It honors yearning: Ira’s letter to the medical school is a kind of faith in human learning; Alma’s childhood friend is a longing for tenderness in a hostile world; Sevelie’s small acts of hospitality become liturgy against cruelty.

The problem is not worship but ownership—the claim that intermediaries can monetize transcendence. By ending with a quiet departure rather than a new creed, the novel imagines faith as an ethical practice divorced from institutional extraction.

Reverence is measured by how one treats the wounded, not by what one can command from the heavens. In exposing sanctity founded on theft, the story asks readers to re-imagine devotion as truth-telling, restitution, and care that does not require a sacrificial victim to validate it.

Love, Companionship, and the Peril of Devotion

At the heart of the book is a relationship that is both shelter and threat. Aster begins as an imaginary friend shaped by a lonely child’s need; he becomes an all-powerful being whose love is possessive, tender, jealous, and finally catastrophic.

The novel is unsentimental about this paradox. Aster’s affection steadies Alma through grief, helps her master the prosthetic, and saves her life more than once; the same affection blinds him to human limits and authorizes destruction in the name of protection.

Devotion without boundaries turns into conquest, and the intimate language of friendship becomes a justification for remaking a city according to private pain. Alma’s response is equally complex.

She is grateful, enthralled, suspicious, and finally resolute, recognizing that love which demands the world burn is love she must resist. The choice to wound Aster, and to accept a wound in return, reads as an argument that care sometimes requires refusing the beloved.

The goodbye is devastating precisely because the book honors what was real in their bond—shared memories, small jokes, the relief of being seen—while insisting that tenderness cannot excuse harm. After Aster’s fall, Alma’s quieter relationships take center stage.

Sevelie’s steadfastness, Six’s trust, and Fion’s invitation offer a model of affection grounded in respect rather than awe. In that shift the novel suggests that the most valuable companions are not those who can move mountains for you, but those who will keep you human when mountains start moving.

Love, to endure, must protect freedom as fiercely as it treasures closeness.

Guilt, Grief, and the Work of Self-Authorship

Alma carries heavy ghosts: shame for the guard’s mutilation, regret over her mother’s death, and the dread that her strength is borrowed from something unforgivable. The inner journey through memory—Ephrem’s letter, the truth about the childhood binding, the revelation that her solace was also an imposition—functions as a ritual of honest accounting.

The book treats grief not as an event but as labor. It shows how sorrow distorts judgment, how hunger for relief can make manipulation feel like care, and how healing requires naming the full story even when it cracks the heart open further.

By letting Ephrem speak, the narrative gives Alma permission to release inherited blame while taking responsibility for her choices. That balance is crucial: she is not defined by the violence done to her, yet she refuses to ignore the violence she has done.

The final chapters resist the easy absolution of cosmic victory. Alma does not ascend; she chooses a road back to Merey, a visit to her mother’s grave, and a future that will demand daily courage rather than public titles.

Self-authorship is modest here. It looks like leaving a ruined capital with a vulnerable child, trusting friendships, and a body that remembers both love and harm.

The fragment of Aster’s power she retains symbolizes a complicated legacy: strength informed by grief but not ruled by it. In walking away, she writes a new first line for herself, one that does not require a god, a house, or a court to certify her worth.

The hope the book offers is not triumph but steadiness—the earned conviction that she can shape a life that honors the dead without becoming their echo.