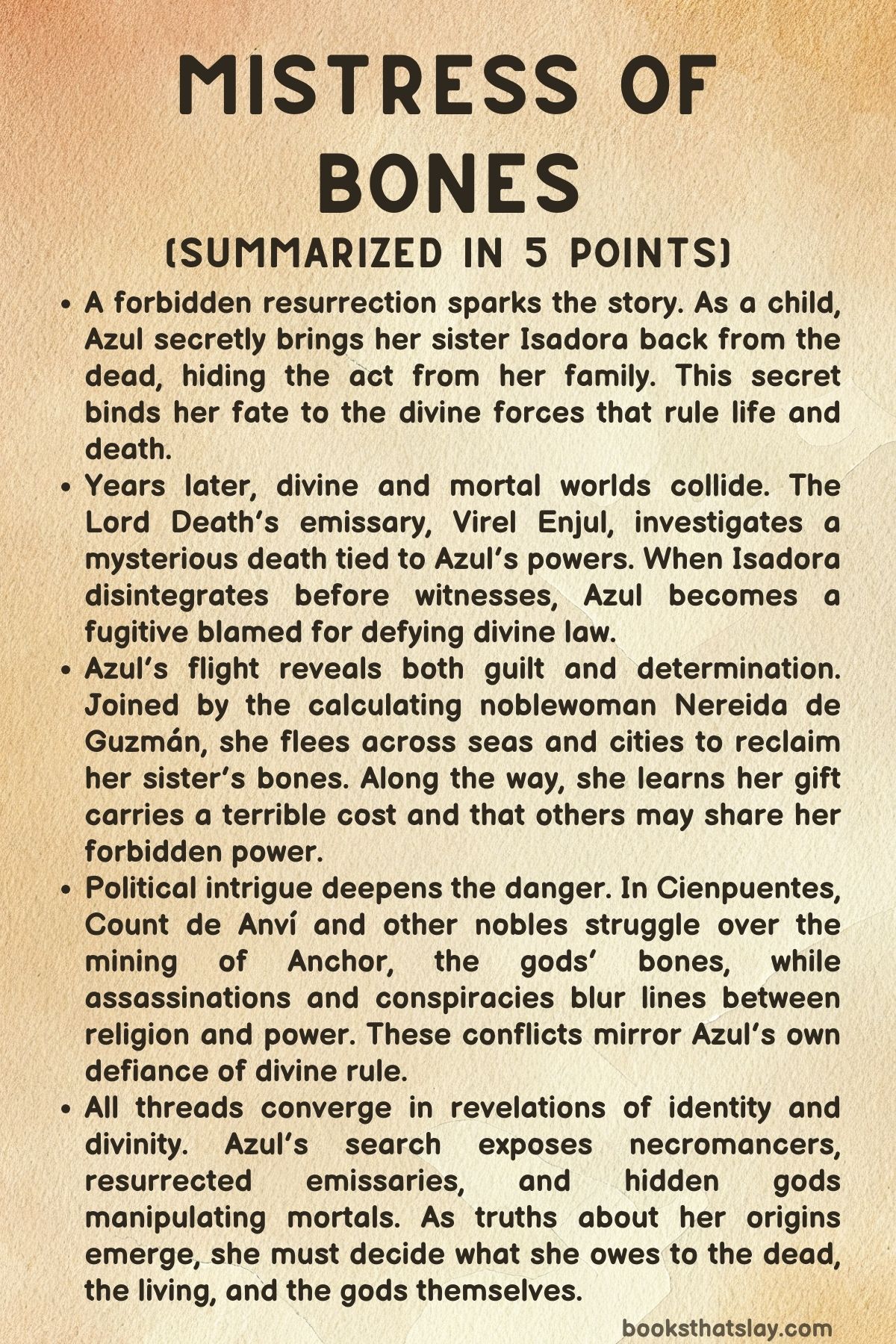

Mistress of Bones Summary, Characters and Themes

Mistress of Bones by Maria Z. Medina is a sweeping dark fantasy that explores the boundaries between life, death, and divinity through the eyes of a defiant young necromancer.

Set across the divided nations of Valanje and Sancia—lands separated by faith and politics—the novel follows Azul del Arroyo, a girl gifted and cursed with the power to bring back the dead. As she resurrects her sister and becomes entangled in political conspiracies, forbidden gods, and shifting loyalties, her story unfolds amid a world where death itself has emissaries, bones carry divine memory, and power demands sacrifice. Medina crafts a complex tale of rebellion, identity, and the cost of creation.

Summary

Azul del Arroyo’s extraordinary gift manifests when she is just ten years old. Stricken by grief after her sister Isadora’s death from fever, she secretly performs a resurrection ritual, cutting off a finger, praying to the gods, and waiting through the night.

Miraculously, Isadora returns to life, though her memories of death are gone. Azul conceals the truth, believing she has outwitted the gods.

For nearly a decade, the sisters live quietly in Sancia—until destiny, and divine law, come to reclaim what was taken.

In Valanje, Virel Enjul serves as Emissary of the Lord Death, studying bones and enforcing the god’s decrees. His peaceful work is disrupted by a strange case: a Sancian woman who dies and turns into greenish dust.

Enjul fears this is a malady—a forbidden act against death—and travels to Diel to investigate. There he meets Rudel Serunje, who reveals that two Sancian sisters recently arrived: Isadora and Azul del Arroyo.

During their disembarkation, Isadora suddenly disintegrated before the horrified crowd, leaving Azul screaming that she needed her sister’s bones. Enjul’s suspicions ignite.

When he confronts Azul, her vitality disturbs him—she feels untouched by death’s mark. Believing her a heretic who has violated divine order, he decides she must be captured alive or dead.

Azul, desperate and terrified, bargains with Nereida de Guzmán, a noblewoman traveling with the envoy. Nereida offers to help her escape if Azul agrees to resurrect someone of her choosing.

The girl admits her secret and explains the ritual’s rules: she needs a bone and something living to rebuild flesh. Together they flee the city under night’s cover, but Enjul intercepts them at the docks.

When he blocks their path, Nereida shoots him dead. Azul flees in horror, burdened by guilt and determination to reclaim her sister’s remains.

Meanwhile, in Sancia’s capital Cienpuentes, Count Emiré de Anví navigates corruption and danger following the queen’s death. He investigates a string of political murders connected to Anchor—the sacred blue mineral that forms the world’s foundation.

Valanje treats Anchor as holy; Sancia mines it recklessly for wealth. De Anví’s uneasy alliance with the mysterious Faceless Witch reveals a larger conspiracy manipulating both faith and politics.

On the run across the sea, Azul travels with Nereida, who demands proof of her power. Forced at sword-point, Azul resurrects a dead bird, shocking Nereida into awe.

When they reach Monteverde, Azul searches for Isadora’s bones but discovers the town has no ossuary—its dead are sent to Cienpuentes instead. Determined to continue, she stays with Lina del Valle, a family friend who shelters them.

Through her psychic link with the resurrected bird, Azul senses danger closing in when the connection abruptly dies.

As Azul flees toward Cienpuentes, De Anví uncovers new threads in the murder of Marquess de Gracia. The Witch suggests the killings aim to overturn the Anchor-mining ban.

Meanwhile, Azul and Nereida are ambushed at an inn by men claiming to escort them under Valanjian orders. They fight back fiercely, and a mysterious figure named Silvo Zenjiel intervenes, taking them to the Valanjian ambassador’s estate.

There, Azul discovers Enjul alive—resurrected in defiance of his own god. When Zenjiel suddenly collapses as a rotted corpse, both realize another necromancer is at work, one powerful enough to reanimate humans as puppets.

Back in Cienpuentes, Miguel Esparza, a guard haunted by past dealings with the dead, is hired by Nereida to infiltrate the ossuary. She conceals her identity while De Anví arranges secret meetings with the Faceless Witch.

The city teems with tension: noble houses plot over Anchor rights, and whispers of necromancy spread. Azul, moving among scholars and artists, learns theories about bones and morality that challenge her understanding of life and decay.

Her hunt for Isadora’s bones intensifies as she realizes her family’s ties to forbidden experiments.

Azul is soon kidnapped by masked men hoping to use her as leverage against her brother Sergado de Gracia, heir to the Marquess. After escaping captivity, she reports to Captain de Macia, who reveals that her father has been murdered.

Shocked and alone, she discovers that her brother is secretly practicing necromancy—using corpses to pursue his own “great project. ” Sergado animates the dead to manipulate politics, supporting Anchor mining in exchange for influence.

His ambition and Azul’s desperation put them on a collision course.

When Azul and the emissary finally meet again, they forge a reluctant alliance. Enjul needs her help to identify the other necromancer’s creations, while she needs his restraint and protection.

Their uneasy truce leads them to the royal Noche Verde celebrations, where political games and necromantic secrets intertwine. Beneath the city’s beauty, corpses walk and gods stir.

Driven by a psychic trail and grim determination, Azul infiltrates Sergado’s hidden estate. She discovers his ghastly experiments—reanimated soldiers and servants made from bone and Anchor.

As she confronts him, the fight turns violent. Enjul, also captured and enslaved by Sergado’s sorcery, stands as a hollow puppet.

Horrified that her brother has violated even the emissary’s will, Azul sacrifices part of her own soul to awaken the divine presence inside Enjul. The Lord Death himself rises, obliterating Sergado’s undead and restoring order.

Azul collapses, drained of life and spirit.

When she awakens, she learns that Death has taken full possession of Enjul’s body. He reveals a final truth: Azul is not a necromancer of death, but a child of the Lord Life—her power creates, not revives.

Isadora cannot return because her essence is gone, but Death promises to retrieve her soul if Azul accompanies him to confront the gods who abandoned the world. Bound by purpose and guilt, she accepts.

Elsewhere, the Faceless Witch, desperate to preserve her fading body, allies with Sergado’s remnants to construct a divine vessel. As new gods begin to awaken, the Witch and De Gracia set out for the frontier city of Bremón, carrying bones filled with divine residue.

The world edges closer to a reckoning between gods and mortals.

Before departing, Azul fulfills a promise to Nereida. Using the last of her strength, she plants a baby tooth in the soil and channels her dwindling essence to restore Nereida’s sister, Edine, to life.

The act drains her nearly to death, but Edine awakens, calling her sister’s name. Nereida embraces her, weeping with gratitude and fear, while Azul accepts her fate.

She must now journey beside the Lord Death himself, seeking her sister’s lost soul and the truth of creation—an odyssey that will determine whether gods or mortals rule life’s fragile boundary.

Characters

Azul del Arroyo

Azul del Arroyo stands at the heart of Mistress of Bones, a figure of both divine curiosity and mortal anguish. From childhood, Azul embodies rebellion against natural law—the first to resurrect her sister Isadora through forbidden prayer and blood.

Her defiance of death shapes her identity, but what begins as love mutates into obsession, isolation, and guilt. Azul’s powers grow as her understanding deepens: she is not merely a necromancer, but a living contradiction—a child of the Lord Life herself, born to create.

Yet this revelation does not grant her peace. It instead underscores her tragedy: all her acts of creation demand a personal cost, each resurrection bleeding her soul thinner.

Her journey across Valanje and Sancia is as much an escape as it is a pilgrimage—a desperate search to reclaim the sister whose death defines her. Through Azul, Maria Z Medina explores faith, morality, and the thin boundary between devotion and blasphemy.

Her character embodies both compassion and destruction, a girl turned woman whose longing for love leads her into war with gods themselves.

Isadora del Arroyo

Isadora, though often absent in body, is omnipresent in spirit throughout Mistress of Bones. She represents memory, loss, and the fragile human longing to reverse the irreversible.

Once resurrected by her sister, Isadora’s life becomes a ghostly echo—a borrowed existence built upon Azul’s sin. The erasure of her memories after resurrection renders her both victim and symbol, her presence a reminder of the unnatural cost of Azul’s gift.

Even in death, her influence propels the narrative: Azul’s every choice and sacrifice circles back to the desire to restore her sister’s essence. Isadora thus functions as both character and catalyst, her fragmented existence blurring the boundaries between life and death, memory and oblivion.

Virel Enjul

Virel Enjul, the Emissary of the Lord Death, is a man torn between duty and fascination. Bound by divine law to hunt and eradicate necromancy, Enjul sees Azul as an abomination—an affront to his god’s order.

Yet the more he pursues her, the more she mirrors his own contradictions. His life as a scholar of bones and servant of Death’s will transforms into something conflicted when confronted by Azul’s defiance.

Enjul’s resurrection and later possession by the Lord Death himself mark his transformation from devout emissary to vessel of divinity. Through him, Medina examines the consequences of absolute obedience and the nature of faith.

Enjul’s tragedy lies in his loyalty; his body becomes the battlefield where gods and mortals wrestle for dominion, and his humanity is the price of their war.

Nereida de Guzmán

Nereida de Guzmán is an aristocrat cloaked in command and sorrow. Once a noblewoman entangled in royal affairs, she carries herself with authority and cynicism.

Her partnership with Azul begins as manipulation—an attempt to exploit the girl’s necromantic abilities for her own ends—but evolves into a relationship shaded by mutual need and fragile affection. Nereida’s fascination with resurrection stems from personal loss, culminating in her plea for Azul to bring back her sister Edine.

Her character oscillates between control and vulnerability, her pragmatic cruelty tempered by flashes of tenderness. Through Nereida, the novel examines how grief corrupts love and how power can disguise desperation.

Her final act—risking herself to restore her sister—completes her arc, merging ambition and redemption in one bittersweet gesture.

Count Emiré de Anví

Count Emiré de Anví is the weary conscience of Mistress of Bones’ political world. A noble entangled in the corruption of Cienpuentes, De Anví navigates between morality and survival.

Haunted by past compromises and alliances with the Faceless Witch, he embodies decay—not of body, but of soul. His loyalty to the realm and the crown masks deep exhaustion, his every action a balance between duty and quiet despair.

De Anví’s addiction to Anchor dream-pills reveals his yearning to escape reality, particularly through imagined reunions with Nereida. His storyline exposes the moral erosion of governance and the emptiness of power in a decaying empire.

Through him, Medina gives voice to those who fight corruption yet remain corrupted by proximity to it.

Sergado de Gracia

Sergado de Gracia, heir to a corrupted legacy, represents the descent of intellect into madness. Initially indifferent to politics, his fascination with necromancy transforms him into a scientist of the profane.

His pursuit of control over bones—both literal and symbolic—reflects the human desire to master death. Unlike Azul, who gives life through empathy, Sergado manipulates the dead for dominion.

His “great project,” seeking to shape godlike beings from divine remnants, reveals ambition devoid of morality. When he reanimates Virel Enjul as a puppet, his depravity reaches its peak, provoking Azul’s fury and Death’s direct intervention.

Sergado personifies the corruption born from intellect without conscience—a mirror image of Azul’s creation twisted into desecration.

The Faceless Witch

The Faceless Witch threads through the story as a force of chaos and hidden truth. Neither entirely villain nor ally, she embodies the liminal space between knowledge and monstrosity.

Her ability to inhabit bodies, including that of Sío de Guzmán, blurs the boundaries of identity and morality. The Witch’s pursuit of perfect vessels and her dealings with Sergado reveal a perverse imitation of divine creation, contrasting Azul’s life-giving power.

Her manipulations in court, her connection to the gods’ awakening, and her final possession by another divine presence elevate her from sorcerer to prophet of apocalypse. She stands as a reflection of humanity’s desire to transcend mortality and the catastrophic cost of doing so.

Miguel Esparza

Miguel Esparza serves as the grounded voice amid the novel’s swirl of mysticism and politics. A loyal guard with a haunted past, Esparza moves uneasily between the realms of the living and the dead.

His earlier intrusion into the Royal Crypt and his encounters with Nereida and De Anví root him in moral ambiguity—an ordinary man forced to witness extraordinary blasphemies. Through him, Medina explores the toll of obedience and fear in a world unraveling under divine interference.

His interactions with Nereida expose the limits of loyalty and the quiet bravery of those without power who still choose to act.

Edine de Guzmán

Edine, the youngest Guzmán sister, embodies innocence and sacrifice. Though her role unfolds in fragments and flashbacks, her resurrection in the final scenes crystallizes the novel’s themes of love, faith, and creation.

Edine’s return from death, facilitated by Azul at Nereida’s plea, signifies not just the triumph of life over death but also the final erosion of Azul’s own essence. Her rebirth is both miracle and curse—a reminder that creation demands destruction.

Edine’s presence closes the circle of loss that began with Isadora’s death, offering fragile hope amid divine conflict.

Themes

Defiance of Divine Order and the Boundaries Between Life and Death

The world of Mistress of Bones is built on an understanding that death is absolute and sacred, a law enforced by the Lord Death and his emissaries. Azul del Arroyo’s act of resurrecting her sister Isadora shatters that fundamental truth.

Her defiance represents not just rebellion against divine order, but a challenge to the idea that mortality defines humanity. Through her, the novel examines the emotional and moral consequences of resisting nature’s limits.

Azul’s necromancy is not rooted in ambition or arrogance—it springs from love and grief. Yet, every act of resurrection exacts a toll, not just on her body and soul, but on the balance of the world.

The story constantly returns to the tension between compassion and transgression: is Azul’s power a gift of life or a curse that desecrates creation? This conflict becomes more complex with Virel Enjul’s resurrection and the revelation that Azul herself embodies the essence of Life.

The divine dichotomy between Life and Death is no longer abstract theology—it becomes embodied conflict, waged through Azul and Enjul, each representing forces that once maintained harmony but now drift toward confrontation. The book treats resurrection not as a miracle, but as a philosophical question: if death can be undone, what becomes of meaning, morality, or faith?

Through Azul’s journey, Maria Z Medina exposes how both gods and mortals are prisoners of the laws they claim to control, and how breaking those laws reshapes not only existence but the very identity of the soul.

Grief, Love, and the Price of Attachment

At its emotional center, Mistress of Bones is a story of love distorted by grief. Azul’s resurrection of Isadora is an act of devotion that fractures reality.

Love, here, is both creative and destructive—it drives Azul to challenge death itself, yet it also blinds her to the consequences of her actions. Medina uses this relationship to show how grief transforms purity into obsession.

Azul cannot accept separation, and in her attempt to preserve what she loves, she becomes a conduit for forces far beyond her understanding. Every subsequent decision—her alliance with Nereida, her willingness to sacrifice part of her soul, her compulsion to “fix” what she lost—emerges from that same grief-fueled need to reverse time.

Nereida’s relationship with her own sister, Edine, mirrors Azul’s in tragic symmetry. Her resurrection of Edine at the novel’s end echoes Azul’s first sin, creating a cyclical pattern of love’s destructive persistence.

Medina suggests that love’s power is neither wholly good nor evil; it is a force that gives life meaning yet tempts mortals to defy the natural order. The novel’s emotional tension thrives in this paradox—where affection demands transgression, and mourning becomes an act of rebellion.

By showing the devastation that follows attempts to rewrite fate, Medina turns personal grief into a reflection on human frailty: that the heart’s refusal to accept loss may be the most dangerous magic of all.

Power, Corruption, and the Politics of the Sacred

Beyond personal tragedy, Mistress of Bones unfolds against a backdrop of political greed and divine hypocrisy. The tension between Sancia and Valanje over the mining of Anchor—believed to be the gods’ bones—embodies humanity’s manipulation of the sacred for power.

What one nation calls faith, another calls resource. Through Count De Anví, Nereida, and the scheming nobles of Cienpuentes, Medina exposes how religion and politics intertwine to justify exploitation.

Anchor becomes both symbol and weapon—a material embodiment of divine creation reduced to economic leverage. The Order of Death, charged with preserving divine law, is not immune to this corruption; its emissaries wield faith as control, enforcing orthodoxy while serving political agendas.

Enjul, though devout, becomes a tragic figure trapped between belief and truth, realizing too late that divine authority is as flawed as human ambition. The book suggests that corruption stems not merely from greed but from the institutionalization of belief itself.

When gods and governments claim ownership over life, death, and resurrection, morality collapses into rhetoric. Medina’s portrayal of divine emissaries, royal guards, and conspirators blurs distinctions between the sacred and profane, revealing that the pursuit of control—whether over souls, resources, or destiny—is the true blasphemy.

Identity, Divinity, and the Nature of Creation

As Azul’s journey progresses, her understanding of herself transforms from necromancer to something far more profound: a child of the Lord Life. This revelation reframes every moral question the book raises.

She was never merely reanimating corpses—she was creating. Medina uses this discovery to examine what it means to be human in a world defined by divine hierarchy.

If Azul is the vessel of Life itself, then creation and destruction cease to be opposites—they become complementary forces necessary for existence. Her ability to breathe life into matter contrasts with Enjul’s role as arbiter of endings, suggesting that divinity is not an external authority but an intrinsic part of being.

Azul’s struggle to define herself—monster, savior, or god—reflects humanity’s own search for purpose in a universe governed by unseen powers. Through her, the novel explores the fear of one’s potential and the loneliness that accompanies transcendence.

Her creations, from resurrected animals to the reborn Edine, are extensions of her soul, each act depleting her essence, forcing her to confront the cost of becoming divine. Medina’s vision of creation is not triumphant—it is sacrificial.

To create is to lose a part of oneself, to risk dissolution in the process of giving life. Thus, Mistress of Bones turns the idea of godhood into a burden rather than a privilege, portraying divinity as the ultimate test of humanity’s will to endure.

The Collision of Faith and Reason

Throughout Mistress of Bones, faith and rational inquiry collide in both personal and societal dimensions. Characters like Enjul embody blind devotion to divine law, while figures such as De Anví and Norelda represent the pragmatic skepticism of a world that has begun to question mythic truths.

The society of Cienpuentes is steeped in theological governance, yet its people are restless, driven by science, trade, and ambition. Necromancy itself becomes the field where faith and reason clash—the miracle of resurrection viewed as both sacrilege and discovery.

Azul’s power exists at the intersection of these realms; her actions are condemned by priests yet studied by scholars. Medina uses this tension to critique dogma, suggesting that knowledge and faith are not mutually exclusive but are corrupted when used to dominate rather than to understand.

The philosophical conflict between divine will and human curiosity gives the novel its intellectual depth: if humans are created in the image of gods, then their pursuit of forbidden knowledge may be an act of divine imitation rather than defiance. By blurring the lines between spiritual reverence and empirical exploration, the narrative asks whether enlightenment requires faith’s destruction—or whether faith, redefined through compassion and self-awareness, can survive in a world where gods bleed and mortals create life.