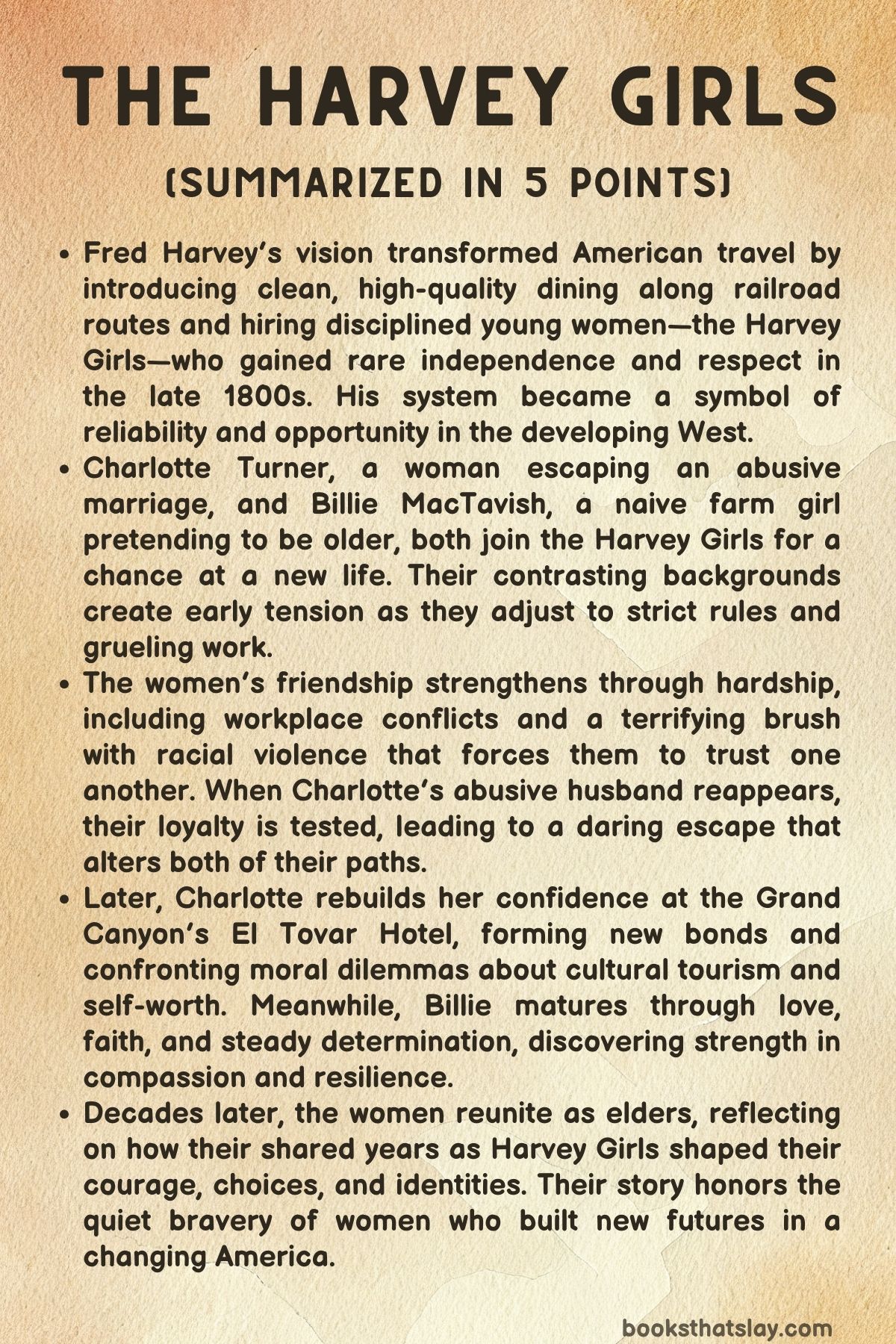

The Harvey Girls Summary, Characters and Themes

The Harvey Girls by Juliette Fay tells the story of two women who find transformation and strength through the Fred Harvey Company, the hospitality empire that helped civilize the American West. The novel intertwines historical events with personal struggles of survival, independence, and friendship.

Set between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it explores how the Harvey Houses gave young women a chance at self-reliance and dignity in a time when such opportunities were rare. Through Charlotte Turner, a woman fleeing abuse, and Billie MacTavish, a teenager seeking a better life, the book captures the courage it took to forge new identities in an unforgiving landscape.

Summary

Fred Harvey, an English immigrant who began as a dishwasher in New York, rose through the ranks of the restaurant industry and eventually transformed American travel dining. His vision led to the creation of Harvey Houses along railroad depots, offering travelers fresh, well-prepared meals and introducing a new standard of service.

To staff these establishments, he hired young women—the Harvey Girls—who followed strict rules but gained rare independence, wages, and respect. Many later married, settled, and helped shape towns across the Southwest.

In Kansas City decades later, two women’s lives cross under very different circumstances. Charlotte Turner, once from a refined Boston background, hides in a train station, concealing a bruised face from her abusive husband, Simeon Lister.

Fleeing her marriage, she adopts a false identity and interviews with Miss Steele, the firm yet perceptive head of personnel for Fred Harvey. Despite noticing Charlotte’s injury, Miss Steele offers her a position, recognizing her need for a new beginning.

Elsewhere in the station, fifteen-year-old Wilamena “Billie” MacTavish arrives with her mother from Nebraska. Her family is poor, and her mother hopes the Harvey job will offer a way out of hardship.

Pretending to be eighteen, Billie impresses Miss Steele with her mix of honesty and enthusiasm. After a tearful farewell to her mother, she spends the night alone in the station before joining the next morning’s train to Topeka, where both she and Charlotte will begin their training as Harvey Girls.

During breakfast, Charlotte and Billie meet briefly. Billie, unrefined and nervous, marvels at her first real restaurant meal, while Charlotte, poised but guarded, helps her navigate the menu.

They soon board the train bound for Topeka—Billie gazing in wonder at the open plains, Charlotte finding rare peace in sleep after days of fear. Upon arrival, they are introduced to the disciplined life of the Harvey House: brisk service, spotless uniforms, and high expectations.

Frances, the head waitress, demands excellence and assigns them menial tasks as part of their initiation. Charlotte’s composure helps her adapt quickly, but Billie’s inexperience causes blunders that nearly cost them their jobs.

Only Frances’s grudging recognition of their potential saves them from dismissal.

Their early days are grueling. Charlotte struggles with physical exhaustion, Billie with homesickness and mistakes.

When Charlotte defends a showgirl from a lewd diner by spilling hot soup on him, she expects reprimand but earns respect instead. The act marks the start of her healing and Billie’s growing admiration.

Slowly, they begin to support each other amid the demands of long shifts and rigid rules.

Their fragile friendship deepens after a violent incident. While attending Mass with a coworker, Billie witnesses a Ku Klux Klan attack on a Mexican busboy, Pablocito.

Charlotte intervenes to save her, and though both are terrified, the experience binds them. Their photograph appears in a newspaper, sparking Charlotte’s fear that Simeon might find her.

That night, the two finally share their secrets: Charlotte admits she’s married and running from abuse; Billie confesses she’s underage. Trust begins to replace distance between them.

Their fears soon come true when Simeon appears in Topeka, pretending to have reformed. He manipulates Charlotte into believing he has changed, though Billie and Leif, a kind kitchen worker, sense danger.

During a confrontation at the Harvey House, Simeon’s rage explodes. Frances and Leif intervene, allowing Charlotte to escape west on a train.

Billie remains behind, heartbroken but relieved that her friend is alive. She continues her work, visits Pablocito as he recovers, and grows close to Leif.

Independence and compassion begin to replace her youthful uncertainty.

Charlotte’s train journey leads her to Williams, Arizona, where she is transferred to work at the Grand Canyon’s El Tovar Hotel. Years pass, and both women find themselves reunited there in 1926.

Charlotte, older and cautious, avoids social gatherings, still haunted by her past. Billie, now more confident, convinces her to attend a local dance.

There, Charlotte meets Will, a kind driver who gently restores her faith in companionship. Billie, meanwhile, enjoys the company of Robert, a park ranger, though her innocence leads her into small troubles—like unknowingly drinking spiked punch.

Life at El Tovar blends hard work with moments of friendship and self-discovery. Billie grows close to Leif, while Charlotte wrestles with conflicting emotions about Will and her own guilt over the past.

When she receives an offer to join the prestigious “Indian Detours” program—a guided cultural tour through Native lands—she hesitates after a Navajo clerk condemns the program as exploitative. Confused, she turns to Will, and the two confess their love.

For the first time since fleeing Simeon, Charlotte allows herself to be vulnerable, finding comfort and peace in his affection.

Their happiness is short-lived. Simeon tracks Charlotte to the Grand Canyon, arriving in a frenzy.

She flees through the hotel and down the Bright Angel Trail, hiding on a ledge. When Simeon corners her, a struggle ensues.

Billie appears, calling out just as Simeon lunges; he loses balance and falls into the canyon. The event ends Charlotte’s years of running but brings scandal.

The Harvey management fires her and Will for violating rules, though police later deem Simeon’s death accidental.

In the aftermath, Charlotte plans to return east to reconcile with her family. Will invites her to his family’s farm, but she needs time to rebuild trust in herself.

Billie arranges to transfer to Ash Fork, where Leif will also be stationed, hoping for a quieter life. As Charlotte leaves, she gifts her clothes to other Harvey Girls and sends an apology to John, the Navajo clerk who had challenged her perspective.

Decades later, both women reunite at the Grand Canyon as elderly ladies. Billie, now eighty-six, visits with her granddaughter, while Charlotte, in her nineties, arrives with her grandson.

Over lunch, they share stories of the lives they built—Charlotte became a professor and married Will, while Billie found faith, work, and joy in the world she once feared. Their reunion is tender and filled with humor, closing the circle on their years of courage and transformation.

As their families drive them away, they promise each other that, even after all this time, they are still Harvey Girls—ready for anything life may bring.

Characters

Fred Harvey

Fred Harvey stands as the foundational figure in The Harvey Girls, representing both ambition and innovation in a rapidly industrializing America. As a young English immigrant who begins humbly as a dishwasher, Fred embodies the American dream through perseverance, vision, and integrity.

His relentless pursuit of excellence in hospitality leads to the creation of the Harvey House chain, a model of refinement and order amidst the rugged expansion of the American West. Beyond his entrepreneurial spirit, Fred’s legacy lies in the empowerment of women—offering them employment, education in manners and efficiency, and a means to independence.

His character, though appearing largely in the background, symbolizes progress, civility, and the power of structured opportunity in a chaotic era.

Charlotte Turner

Charlotte Turner is one of the emotional anchors of The Harvey Girls, her story marked by resilience, trauma, and transformation. Once a privileged woman from Boston, she escapes an abusive marriage to Simeon Lister, adopting a false identity to reclaim control over her life.

Charlotte’s composure, intellect, and refinement contrast with the raw frontier around her, yet beneath her poise lies deep fear and guilt. Her journey from victimhood to self-assertion unfolds gradually—first through small acts of courage, then through defiance against both societal norms and her violent husband.

Her time as a Harvey Girl strips her of privilege but restores her dignity; work becomes her salvation. Charlotte’s relationship with Billie mirrors that of mentor and reluctant friend, highlighting her internal battle between vulnerability and restraint.

In her later years, her achievements as a scholar and educator complete a full arc from repression to autonomy, embodying the story’s feminist core.

Wilamena “Billie” MacTavish

Billie MacTavish represents innocence, growth, and the resilient optimism of youth. A fifteen-year-old from a poor Nebraska family, she lies about her age to secure work and lift her family’s fortunes.

Her naïveté and clumsiness initially set her apart, but her earnest heart and emotional intelligence quickly endear her to colleagues and customers alike. Billie’s moral compass and empathy become the novel’s moral grounding—her instinct to protect others, whether defending a friend or comforting the injured, shows a courage rooted in love rather than pride.

Her friendship with Charlotte becomes transformative, bridging class and experience. While Charlotte teaches her decorum and discipline, Billie’s sincerity teaches Charlotte trust and emotional freedom.

Her gradual maturation—from homesick girl to confident woman who builds her own path—reflects the broader journey of the Harvey Girls: young women forging identity and purpose through hard work, solidarity, and courage.

Simeon Lister

Simeon Lister is a chilling embodiment of charm corrupted by control and ego. Once a charismatic journalist, he descends into alcoholism and cruelty, turning marriage into a cage for Charlotte.

His intelligence makes him persuasive and dangerous; he manipulates remorse to regain power. Simeon’s reappearance in Charlotte’s life reawakens her trauma and forces her ultimate confrontation with fear.

His death—falling into the Grand Canyon during a violent pursuit—serves as both literal and symbolic release, the abyss swallowing the tyranny of her past. Simeon’s character explores the darker undercurrent of patriarchal authority, illustrating how love, when twisted by domination, can destroy both the abuser and the abused.

Miss Steele

Miss Steele, the composed head of Fred Harvey’s personnel division, acts as a gatekeeper of dignity and discipline within the Harvey system. Her sharp perception and stern fairness balance authority with empathy.

By hiring both Charlotte and Billie despite their imperfections, she becomes a silent architect of their redemption. Miss Steele’s professionalism exemplifies the ideal Harvey Girl—disciplined, perceptive, and dignified—and she stands as an early model of female leadership in a male-dominated world.

Though her presence is limited, her influence echoes throughout the women’s journeys, representing structure, mentorship, and the belief in second chances.

Frances

Frances, the formidable head waitress, represents the demanding, often thankless leadership that holds the Harvey empire together. Blunt, strict, and unsparing, she embodies the Harvey House ethos of perfection under pressure.

Yet beneath her harshness lies profound compassion, revealed when she helps Charlotte escape Simeon. Her own backstory—marked by the tragic loss of her sister to male violence—explains her relentless insistence on discipline as both protection and survival.

Frances becomes a quiet guardian figure, ensuring that no other woman under her care meets the same fate her sister did.

Leif Gunnarsson

Leif Gunnarsson, the kind and reserved kitchen worker, serves as a stabilizing force within The Harvey Girls. Scarred by personal loss and orphaned by tragedy, he brings a gentle resilience to his interactions with others, especially Billie.

Their relationship, founded on mutual respect and shared hardship, grows into a tender love that grounds the story’s emotional core. Leif’s humility and decency contrast with the arrogance of men like Simeon, reinforcing the theme that strength lies in empathy, not dominance.

His friendship with Will and quiet heroism during Charlotte’s escape highlight his moral depth and integrity.

Will

Will, the Harvey driver and later Charlotte’s romantic partner, represents renewal and healing after trauma. His compassion, steadiness, and understanding of pain mirror Charlotte’s own wounds.

Having grown up under an abusive father, Will provides emotional refuge without imposing control. His relationship with Charlotte is mature, based on equality and respect—an antidote to her previous entrapment.

Through Will, the novel explores love as partnership rather than possession. Their eventual marriage and shared scholarly life symbolize redemption not through rescue, but through companionship grounded in shared humanity.

John Honanie

John Honanie, the Navajo clerk and cultural critic of the Harvey Detours, introduces a vital moral dimension to the novel. His confrontation with Charlotte challenges her—and the reader—to recognize the exploitative nature of tourism and cultural commodification.

John’s anger is not merely personal but historical, representing Indigenous resistance to romanticized narratives of the American West. His influence sparks Charlotte’s moral awakening, compelling her to reject the Detours and reconsider her own participation in systemic injustice.

Though his presence is brief, his impact is profound, shifting the story’s focus from personal survival to ethical responsibility.

Pablocito

Pablocito, the kind Mexican busboy and Billie’s friend, embodies innocence and the racial prejudices simmering beneath early twentieth-century America. His brutal attack by the Ku Klux Klan reveals the dangers faced by minorities even in supposedly civilized spaces.

Billie’s attempt to defend him exposes her courage and moral clarity, while the incident catalyzes Charlotte’s exposure fears and emotional unraveling. Pablocito’s survival, fragile yet dignified, becomes a testament to endurance amid cruelty, reinforcing the novel’s wider theme of compassion transcending social divides.

Oliver Turner

Oliver, Charlotte’s brother, serves as a link between her fractured past and her tentative reconciliation with home. His pragmatism and loyalty contrast with the rigidity of their parents, and his willingness to protect Charlotte’s secret shows quiet heroism.

Oliver represents familial love stripped of judgment, offering Charlotte a path toward healing and reintegration without erasing her autonomy.

Henny and Nora

Henny and Nora, fellow Harvey Girls and later lifelong friends of Charlotte and Billie, symbolize the sisterhood that defines the Harvey experience. Their loyalty during Charlotte’s crisis and their shared fate—dying together in a WWII clubmobile—underscore the enduring spirit of camaraderie and courage that the Harvey Girls embodied.

Through them, the narrative honors the countless unnamed women whose labor and bravery shaped the American frontier.

Themes

Female Independence and Empowerment

In The Harvey Girls, Juliette Fay explores how work and opportunity transform women’s lives in an era when independence was rarely granted to them. The Harvey system, with its strict discipline and professional standards, becomes a paradoxical refuge—demanding conformity yet offering liberation.

Charlotte and Billie, from vastly different backgrounds, find within its confines the chance to define themselves outside domestic or familial control. For Charlotte, fleeing an abusive husband, the uniform and rules represent safety and the ability to live on her own terms, even if under watchful eyes.

Billie, meanwhile, begins as a naïve farm girl but grows into a confident young woman capable of supporting herself and making choices without male permission. Their journey shows that empowerment is not always loud or revolutionary; it often grows quietly through labor, self-respect, and solidarity.

The work’s structure—so precise it borders on militaristic—paradoxically becomes the means through which these women assert their autonomy. Fay illustrates how even within restrictive boundaries, women could find purpose, friendship, and the pride of financial and moral independence, challenging the cultural belief that a woman’s worth was tied to her home or husband.

The Harvey Girls’ poised professionalism laid early groundwork for later movements of women’s equality by proving that competence and respect could coexist with femininity.

Class and Social Mobility

Class distinction plays a defining role in the novel’s emotional and moral conflicts. Charlotte’s fall from privilege exposes the fragility of status based on marriage and reputation.

Once an educated woman of Boston society, she is forced to rebuild her life from the bottom, stripped of wealth and security. Billie, conversely, begins in poverty and experiences for the first time the dignity of clean uniforms, good food, and steady pay.

Their intersecting paths reveal how the Harvey Houses became one of the few spaces in early twentieth-century America where class lines blurred, at least temporarily, through shared labor and merit. The dining rooms themselves—polished sanctuaries beside dusty depots—symbolize this fragile social bridge, offering working-class travelers and servers glimpses of refinement that would have otherwise been inaccessible.

Fay also shows how class is intertwined with self-perception: Charlotte’s initial disdain for Billie’s rough manners gives way to admiration for her optimism and resilience, while Billie learns that refinement need not mean superiority. The novel critiques a society that measures worth by birth or decorum rather than integrity, suggesting that dignity is earned through character and effort.

Ultimately, both women’s journeys demonstrate that true elevation comes not from wealth but from self-mastery and moral strength.

Violence, Trauma, and Healing

Beneath the camaraderie and progressivism of the Harvey world runs a current of deep trauma. Charlotte’s past with Simeon Lister defines her fear, shame, and guardedness.

Her story reflects the silent epidemic of domestic violence at a time when women had little legal recourse and social stigma kept them bound to their abusers. Fay portrays Charlotte’s escape not as a single act of rebellion but as a long, painful recovery—one that involves trust, work, and confronting her own self-doubt.

The novel refuses to simplify healing: even in safety, Charlotte’s fear lingers, resurfacing when she faces authority or male attention. Her eventual confrontation with Simeon on the canyon rim becomes both literal and symbolic—the final break from her tormentor and the rebirth of her agency.

Billie’s own trauma, though less direct, comes through witnessing racial violence at the KKK rally, which shatters her innocence and forces her to recognize cruelty beyond her control. Healing, in both arcs, emerges not through vengeance but through solidarity and compassion—Charlotte’s friendship with Billie, Will’s patience, and the women’s shared labor.

Fay’s depiction of survival honors the quiet strength required to rebuild a sense of self after violation, emphasizing resilience as a moral victory over the violence that sought to define them.

Friendship and Found Family

At the heart of The Harvey Girls lies the evolving friendship between Charlotte and Billie, a relationship that transcends age, class, and experience. Their bond begins in misunderstanding and grows through shared trials, forming a surrogate family in a world that often isolates women who stray from convention.

The dormitories and dining halls of the Harvey system function as both workplace and home, where affection must coexist with discipline and hierarchy. Through Billie’s youthful warmth and Charlotte’s protective instincts, Fay crafts a portrait of friendship that is neither idealized nor static.

It is shaped by conflict, forgiveness, and the courage to trust again. When Charlotte confides her secret or when Billie risks her safety to save her, the relationship evolves into a partnership rooted in empathy and equality.

In later years, as they meet again at the Grand Canyon, their enduring affection affirms the transformative power of chosen family. In a society where women were defined by their ties to fathers or husbands, their companionship redefines belonging as something created, not assigned.

Fay’s portrayal of this enduring friendship celebrates the solidarity of women who find strength in one another, proving that emotional kinship can be as sustaining as blood or marriage.

Cultural Identity and Moral Responsibility

The novel also grapples with the cultural and ethical tensions of expansion in the American Southwest. Through Charlotte’s interactions with John Honanie and her growing unease about the “Indian Detours,” Fay examines how progress often masked exploitation.

The Harvey Company’s mission to showcase Native culture to tourists is portrayed with both admiration and discomfort—it brings economic opportunity but also commodifies sacred traditions. Charlotte’s moral awakening, influenced by her conversations with John, marks a turning point where she begins to question her complicity in a system that profits from spectacle.

Her eventual apology acknowledges the complexity of admiration and appropriation, capturing a nuanced moment of self-awareness rare for the time. The Grand Canyon setting becomes a metaphor for moral depth—beautiful yet shadowed by history.

By engaging with issues of cultural representation, Fay broadens the novel’s scope beyond personal redemption to include social conscience. She suggests that integrity is measured not only by private virtue but by one’s willingness to confront the ethical costs of comfort and progress.

Transformation and Renewal

Every thread of The Harvey Girls leads toward transformation—of self, of community, and of opportunity. Both heroines begin as fugitives from their pasts: Charlotte from abuse, Billie from poverty.

Through work, courage, and connection, they remake themselves into women who no longer define their lives by fear or circumstance. The Harvey system, though rigid, becomes a crucible for reinvention; its emphasis on punctuality, precision, and public grace teaches discipline that translates into confidence.

Even secondary characters—Frances, Will, Leif—embody aspects of renewal, each striving to heal from loss or regret. The concluding reunion decades later, with Billie and Charlotte as elderly women, affirms the endurance of growth.

Their lives, though marked by hardship, become examples of what it means to live fully and ethically in the wake of suffering. Fay’s narrative suggests that transformation is less about erasing the past than about integrating it—acknowledging pain while continuing to seek purpose and joy.

In this sense, the book becomes not only a historical novel but a meditation on resilience, illustrating how ordinary individuals can forge extraordinary strength through compassion, labor, and hope.