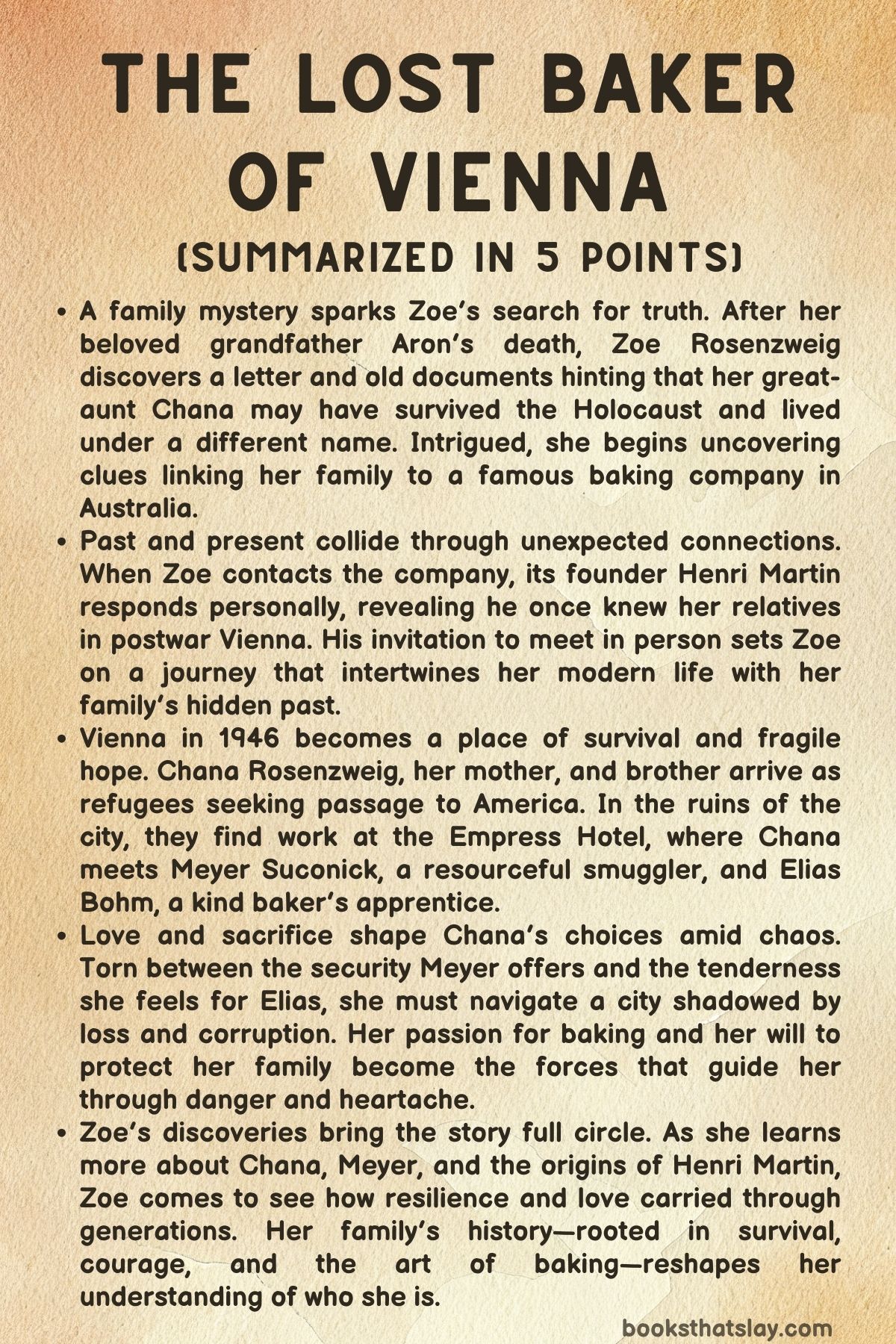

The Lost Baker of Vienna Summary, Characters and Themes

The Lost Baker of Vienna by Sharon Kurtzman is a moving tale of rediscovered history, love, and resilience that connects two generations divided by time and tragedy. The story follows Zoe Rosenzweig, a food journalist from North Carolina, who unravels a decades-old mystery after her grandfather’s death.

Her investigation takes her to postwar Vienna, uncovering the forgotten story of her great-aunt Chana, a Holocaust survivor and gifted baker whose life was marked by courage, love, and loss. Through intertwining timelines, the novel explores how memory, identity, and the pursuit of truth bridge the gap between past and present.

Summary

In February 2018, Zoe Rosenzweig returns to Raleigh from a work trip and visits her grandfather, Aron, who suffers from dementia. During their visit, he mistakes Zoe for his late sister, Chana, and speaks as if she is still alive.

When Aron dies that night, Zoe is left with lingering questions. Sorting through his belongings weeks later, she finds an envelope addressed to her.

Inside are wartime documents and an old magazine article about an Australian baking magnate, Henri Martin. To her shock, a photo of Henri resembles a man named Meyer Suconick, listed as Chana’s husband in the documents.

Determined to uncover the truth, Zoe begins to research.

Her search leads her to contact Martin Baking Company, founded by Henri Martin, and to her surprise, Henri himself calls her. He confirms knowing her family and invites her to meet him in Vienna.

There, he promises to share the real story of Chana Rosenzweig. Zoe, a struggling journalist, convinces her editor to let her cover Henri’s upcoming award ceremony in exchange for an exclusive interview.

Her personal and professional lives intertwine as she travels to Austria—the city where her family’s untold story began.

The narrative shifts to 1946 Vienna. Nineteen-year-old Chana Rosenzweig, her mother Ruth, and her brother Aron arrive in the ruined city after surviving ghettos and concentration camps.

Their guide is Meyer Suconick, a resourceful Brihah operative helping Jewish survivors escape postwar Europe. Though wary of his motives, the Rosenzweigs accept his help.

He finds them work at the once-grand Empress Hotel, where Chana begins laboring in the kitchen. There, she meets Elias Bohm, a kind pastry apprentice whose love of baking rekindles her memories of her father’s bakery before the war.

As Chana settles into life in Vienna, she finds herself drawn to both Meyer and Elias—two men representing different kinds of survival. Meyer is pragmatic and haunted, living by his wits in the dangerous black-market world.

Elias, by contrast, offers tenderness and a sense of normalcy through his baking. When Meyer rescues Chana and her family from a violent attack, her gratitude deepens into conflicted affection.

Yet her mother pressures her to align with Meyer, believing he can secure their emigration to America. This conflict escalates when Chana overhears Meyer and her mother arranging a deal: he will help them leave Europe if Chana agrees to marry him.

Heartbroken, Chana confronts Meyer, accusing him of using her. He admits his heart is too damaged to love but promises to be a good husband.

Torn between duty and desire, Chana consents to the marriage to save her family. Her decision strains her friendship with Elias, who quietly loves her.

Still, Chana’s admiration for Meyer grows when she learns that beneath his dealings, he also helps feed Jewish orphans and smuggles supplies to the needy. Their relationship evolves from obligation to trust, and affection gradually blossoms.

Meanwhile, Zoe in 2018 continues her investigation in Vienna. Henri Martin—now an elderly man—confirms that Chana and her family worked at the Empress Hotel and that Chana was once engaged to Meyer.

When Zoe’s editor betrays her by publishing a sensationalized article about her connection to Henri, her integrity is questioned. Henri’s grandson, Liam, accuses her of exploitation, but Henri forgives her after she confesses her mistake.

He shows her a jeweled comb shaped like a bird—the same one Meyer had once given Chana—and begins recounting the rest of the story.

In 1946, Chana discovers Meyer’s hidden storehouse of goods. Confronted, he explains how his smuggling began as a means of survival and evolved into an effort to support others.

She joins him on a mission to redistribute supplies, and together they deliver food to a convent housing orphaned Jewish children. Through these acts, Chana sees a gentler side of him, and their bond strengthens.

When Meyer takes her family to a celebratory dinner, he openly calls Chana his fiancée, signaling both pride and possessiveness. Though she feels affection for him, she remains conflicted, caught between her growing love for Meyer and the lingering tenderness she feels toward Elias.

The city’s dangers intensify when Meyer’s black-market rivals turn violent. One night, Chana and Elias plan to flee Vienna together, but they stumble upon Meyer being ambushed by his former associates.

In the ensuing chaos, Chana and Elias intervene. Fires spread through the hotel as they fight to escape, and Meyer is gravely wounded.

Despite Elias’s pleas, Chana refuses to leave Meyer behind. Together they rescue him, fleeing to the countryside with the help of Johan and Ursula Bohm, Elias’s relatives.

There, on the Bohm farm, Chana tends to Meyer’s injuries, and they finally admit their love for each other.

When danger returns in the form of Kirill, one of Meyer’s vengeful pursuers, they realize they must flee again. With forged papers under the names Michel and Clair Girard, they cross into Switzerland and later settle in Paris.

There they marry and rebuild their lives, opening a small bakery with a fellow survivor. However, when Kirill tracks them down in 1947, they escape once more—this time to Australia, where they take on new names: Henri and Eveline Martin.

In Sydney, the couple begins anew. Meyer—now Henri—works in a coat factory, while Chana, as Eveline, resumes her passion for baking.

Over the years, their humble bakery grows into the renowned Martin Baking Company. Though haunted by their past, they build a loving marriage and, after years of hardship, welcome a daughter, Rose Dora Martin.

Their success becomes a quiet legacy of endurance and transformation.

Back in 2018, Zoe finally understands the truth: Henri Martin, the man she met in Vienna, is none other than Meyer Suconick. The love story her grandfather never spoke of was one of survival and rebirth.

Chana, who had seemed lost to history, had in fact lived on under a new name—Eveline Martin—and built a life far from the ruins of Vienna. Through Henri’s final confession, Zoe realizes that her family’s history is one not of loss, but of reinvention and courage.

In the end, Zoe’s journey restores the missing pieces of her lineage. The baker once thought lost to time becomes a symbol of endurance and the healing power of memory.

Through Zoe’s discovery, The Lost Baker of Vienna reveals that love, like baking, endures when tended with care—and that even after unimaginable darkness, it is possible to rise again.

Characters

Zoe Rosenzweig

Zoe is the emotional and narrative anchor of The Lost Baker of Vienna, representing the bridge between the scars of the past and the uncertainties of the present. As a food journalist, her profession mirrors the generational legacy of baking that threads through her family history, even though she initially views it as mere career rather than inheritance.

Zoe’s character is defined by her curiosity, empathy, and quiet resilience. The grief she carries over her grandfather’s death becomes the catalyst for her self-discovery, pushing her into an emotional and historical journey that redefines her identity.

Her relationship with Aron—tender and patient despite his dementia—shows her loyalty to family and her deep respect for memory. When she travels to Vienna, Zoe’s transformation intensifies: what begins as a professional assignment evolves into a quest for truth and belonging.

Her moral conflicts with her editor, her confrontation with Henri Martin, and her willingness to face painful truths reveal a woman learning to balance integrity with ambition. Through Zoe, the novel explores how memory, family, and legacy intertwine, showing that even generations removed from trauma can feel its echoes yet find healing through understanding.

Aron Rosenzweig

Aron embodies the fragile persistence of memory and survival. Once a Holocaust survivor and later a loving grandfather, he carries within him both the trauma of loss and the warmth of familial devotion.

His confusion in old age—mistaking Zoe for his sister Chana—symbolizes the blurred lines between past and present that define his existence. Through Aron, the reader sees the lingering emotional costs of survival: guilt, longing, and the fragile comfort found in delusion.

His love for Zoe is unconditional, and his last moments—believing he is reunited with Chana—transform death into a quiet homecoming rather than tragedy. The letter and documents he leaves behind serve as his final act of love, setting in motion the unraveling of family secrets.

Aron’s story reflects the enduring resilience of survivors who carried unbearable histories yet sought peace in ordinary joys. He is a man who, despite his fading mind, preserves the essential truth of love, hope, and continuity.

Chana Rosenzweig

Chana is the luminous soul of The Lost Baker of Vienna, her life story forming the heart of the novel’s historical narrative. A gifted baker and courageous survivor, she is marked by both tragedy and strength.

Her wartime experiences—smuggling messages, enduring ghettos, losing her father, and protecting her family—forge her into a woman of extraordinary resilience. Yet, it is her humanity, not heroism, that defines her: her compassion, her longing to create beauty through baking, and her struggle to choose between love and duty.

Caught between Meyer and Elias, Chana represents the emotional aftermath of survival—how the trauma of loss complicates the possibility of love. Her eventual decision to marry Meyer, not for passion but for her family’s safety, reveals both her sacrifice and her deep moral conviction.

Later, her loyalty and courage during their escape, and her nurturing presence as Eveline Martin in Australia, affirm her as a symbol of rebirth. Through Chana, Sharon Kurtzman captures how women, often overlooked in history’s grand narratives, preserved hope and rebuilt life from ashes.

Meyer Suconick / Henri Martin

Meyer Suconick—later known as Henri Martin—is the most complex and morally ambiguous figure in the novel. A survivor turned smuggler, a man of secrets, he embodies the moral grayness of postwar existence.

Meyer is pragmatic, shrewd, and sometimes ruthless, yet beneath his hard exterior lies profound grief. His involvement in the black market and Brihah’s refugee network blurs the boundary between criminality and necessity; his actions are driven as much by survival as by guilt and vengeance.

His relationship with Chana is turbulent but deeply human—a union forged from pain and redemption. When he transforms into Henri Martin, the respectable baking magnate of Australia, his reinvention reflects both triumph and erasure.

He builds a new identity, a new name, and a new life, yet carries the ghosts of his past. His later tenderness toward Zoe, and his honesty in recounting the truth, suggest a man seeking absolution.

Meyer’s evolution from refugee to patriarch mirrors the novel’s theme: that survival often demands both moral compromise and the courage to rebuild love from ruin.

Elias Bohm

Elias stands as the embodiment of innocence and artistry amid devastation. A young apprentice baker, he represents a gentler vision of postwar healing through creativity and compassion.

His relationship with Chana is tender, untainted by calculation or survival politics. Elias offers her a glimpse of what love could be in a world not governed by loss.

Yet his character also reflects the futility of pure ideals in a time corrupted by fear and necessity. When he steps aside, accepting that Chana’s love for Meyer outweighs her feelings for him, he demonstrates profound emotional maturity.

His quiet departure to pursue a life where he might be “someone’s first choice” becomes one of the story’s most poignant moments. Elias symbolizes the enduring human capacity for kindness and selflessness—even when the world has been reduced to ashes.

Ruth Rosenzweig

Ruth, Chana and Aron’s mother, represents the weary yet indomitable matriarchal force of survival. Her character is shaped by fear, faith, and the relentless drive to protect her children at any cost.

Having witnessed her husband’s death and endured the camps, Ruth becomes pragmatic to the point of severity. Her insistence that Chana marry Meyer, though heartbreaking, springs from desperation rather than greed—she sees in Meyer a chance for safety, for escape from a continent of graves.

Her interactions with Chana are often strained, revealing the generational conflict between idealism and survival. Yet beneath her stern exterior lies deep maternal love.

Ruth’s faith in her daughter’s strength, her trust in Meyer’s promise, and her decision to send Aron ahead to America all reflect a woman who sacrifices everything for her family’s continuity. Through Ruth, the novel pays tribute to the countless mothers who bore the burden of survival so their children might live to dream again.

Henri Martin

In his old age, Henri Martin is a man haunted by the past yet defined by grace and reflection. Having reinvented himself from Meyer Suconick, he becomes both custodian and gatekeeper of memory.

His wealth and success contrast sharply with his reticence and solitude, suggesting that material triumph can never erase moral scars. His decision to reveal the truth to Zoe marks a final act of redemption—an attempt to ensure that the stories of Chana, Aron, and Ruth are not lost to history.

Henri’s interactions with Zoe reveal his vulnerability; beneath his authority lies the same fear of judgment and longing for forgiveness that shadowed his younger self. He embodies the ultimate reconciliation between survival and conscience, a man who has lived many lives but seeks, in his twilight, to reclaim his original name through remembrance.

Themes

Memory and Legacy

In The Lost Baker of Vienna, memory functions as both a burden and a bridge across generations. The novel portrays how memory is not confined to personal recollection but extends into the inherited consciousness of descendants.

Aron’s confusion between his granddaughter Zoe and his long-lost sister Chana reveals how trauma and longing can merge into a single, cyclical recollection. His dementia strips away the boundaries of time, allowing past and present to coexist within his fading mind.

For Zoe, the discovery of her grandfather’s memories—through photographs, documents, and the haunting Vienna phone call—becomes an act of reconstruction. Memory drives her not just toward familial truth but also toward self-understanding.

Through her investigation, the novel exposes how families often carry unspoken histories, where silence itself becomes part of the legacy. Chana’s own recollections of war and loss show memory as both a means of survival and a wound that refuses to heal.

Her act of baking, inherited from her father, becomes a ritual of remembrance—each loaf or pastry an embodiment of what has been lost and preserved. The novel demonstrates how memory refuses to vanish; instead, it adapts, transmitted through recipes, stories, and love.

Ultimately, Zoe’s pursuit of her family’s past transforms memory from an affliction into a source of continuity, suggesting that remembrance, no matter how painful, ensures that the dead remain among the living.

Survival and Moral Ambiguity

Survival in The Lost Baker of Vienna emerges as a moral negotiation rather than a simple act of endurance. After the war, Chana and her family must navigate a shattered world where right and wrong blur into shades of necessity.

Meyer Suconick embodies this complexity—his dealings in the black market, his manipulation of opportunities, and his acts of generosity coexist within the same moral framework. His statement that rebuilding life is “sweet revenge” encapsulates the postwar paradox: survival demands compromise, and morality often bends under the weight of hunger and fear.

Chana’s acceptance of a marriage of convenience to secure her family’s emigration underscores how survival frequently requires sacrifice of personal dreams and emotional truth. Her internal struggle reflects a generation forced to redefine ethics in a world stripped of order.

The novel never romanticizes endurance; instead, it presents it as a daily calculation between conscience and survival. In Zoe’s modern life, the moral questions persist in different form—professional integrity, ambition, and truth-telling.

Her decision to confront her editor and honor Henri’s trust mirrors Chana’s moral reckoning, suggesting that survival in any era involves courage to choose integrity over convenience. The narrative thus portrays survival as a continuum of moral resilience, where endurance is not only physical but ethical, rooted in one’s capacity to remain human amid devastation.

Love and Sacrifice

Love in The Lost Baker of Vienna is portrayed not as an escape from suffering but as its natural companion. Chana’s relationships with Meyer and Elias reveal love’s dual nature—tender yet constrained, passionate yet burdened by obligation.

Her bond with Elias embodies youthful innocence, a longing for purity after the filth of war. In contrast, her love for Meyer grows from shared pain, from two people trying to reclaim humanity through each other.

Their eventual union is both tragic and redemptive, shaped by the recognition that love after trauma must coexist with guilt, fear, and loss. The novel portrays sacrifice as love’s inevitable expression.

Chana’s decision to marry Meyer to save her family exemplifies the painful intersection between devotion and duty. Even in modern times, Zoe inherits this capacity for sacrifice.

She risks her career and reputation to protect Henri’s story, proving that love—in the form of empathy and integrity—transcends time and circumstance. Through these intertwined relationships, the novel asserts that love endures not because it is free of pain but because it chooses persistence in spite of it.

Every act of care, every gesture of forgiveness, becomes a quiet defiance against despair, reaffirming that love, when tested by suffering, reveals its deepest strength.

Identity and Transformation

The theme of identity runs like a current through The Lost Baker of Vienna, exploring how names, professions, and even nationalities can be both masks and truths. Chana’s transformation into Eveline Martin illustrates the human capacity to reconstruct selfhood from fragments.

Her evolution from a Jewish resistance courier to a respected baker in Australia mirrors the reinvention of countless survivors who buried their past to protect their future. The forged papers under new names symbolize not deceit but rebirth—a necessity in a world where survival depends on erasure.

Meyer’s transformation into Henri Martin parallels hers, reflecting how trauma demands reinvention yet never allows full escape. Their bakery becomes a metaphor for reclamation, where creation replaces destruction and craft restores dignity.

Zoe’s own search for identity mirrors this postwar rebirth. Through uncovering her family’s secret past, she discovers her professional and emotional voice.

The novel suggests that identity is not fixed; it evolves through memory, loss, and renewal. Each generation redefines who they are by confronting the truths buried before them.

In connecting Chana’s flour-dusted hands to Zoe’s journalistic pursuit, the story asserts that identity, like dough, must be worked and reshaped to rise anew, sustained by the invisible yeast of memory and love.

The Healing Power of Art and Craft

Throughout The Lost Baker of Vienna, baking serves as the novel’s central symbol of healing and creation. For Chana, the act of baking reconnects her to her father and the lost world of prewar innocence.

In the midst of Vienna’s ruins, the smell of bread and the touch of dough offer stability when everything else has been shattered. Baking becomes a silent language of resilience—a way to express grief, hope, and remembrance without words.

In creating food, she restores her sense of purpose, turning nourishment into art. Meyer and Chana’s bakery in Australia represents the culmination of this redemptive process: out of ashes and loss arises something that sustains others.

The novel suggests that art—in this case, the artistry of baking—possesses the power to transform pain into beauty and survival into legacy. Zoe’s profession as a food journalist continues this lineage, her writing an act of preservation that echoes Chana’s ovens.

The sensory world of taste, texture, and aroma connects generations, bridging the silence of trauma through creation. The novel’s closing image—of life rebuilt through the shared language of craft—underscores that art is not merely a vocation but a way of mending the soul.

Through creation, both Chana and Zoe reclaim agency, proving that what is made with the hands can also heal the heart.