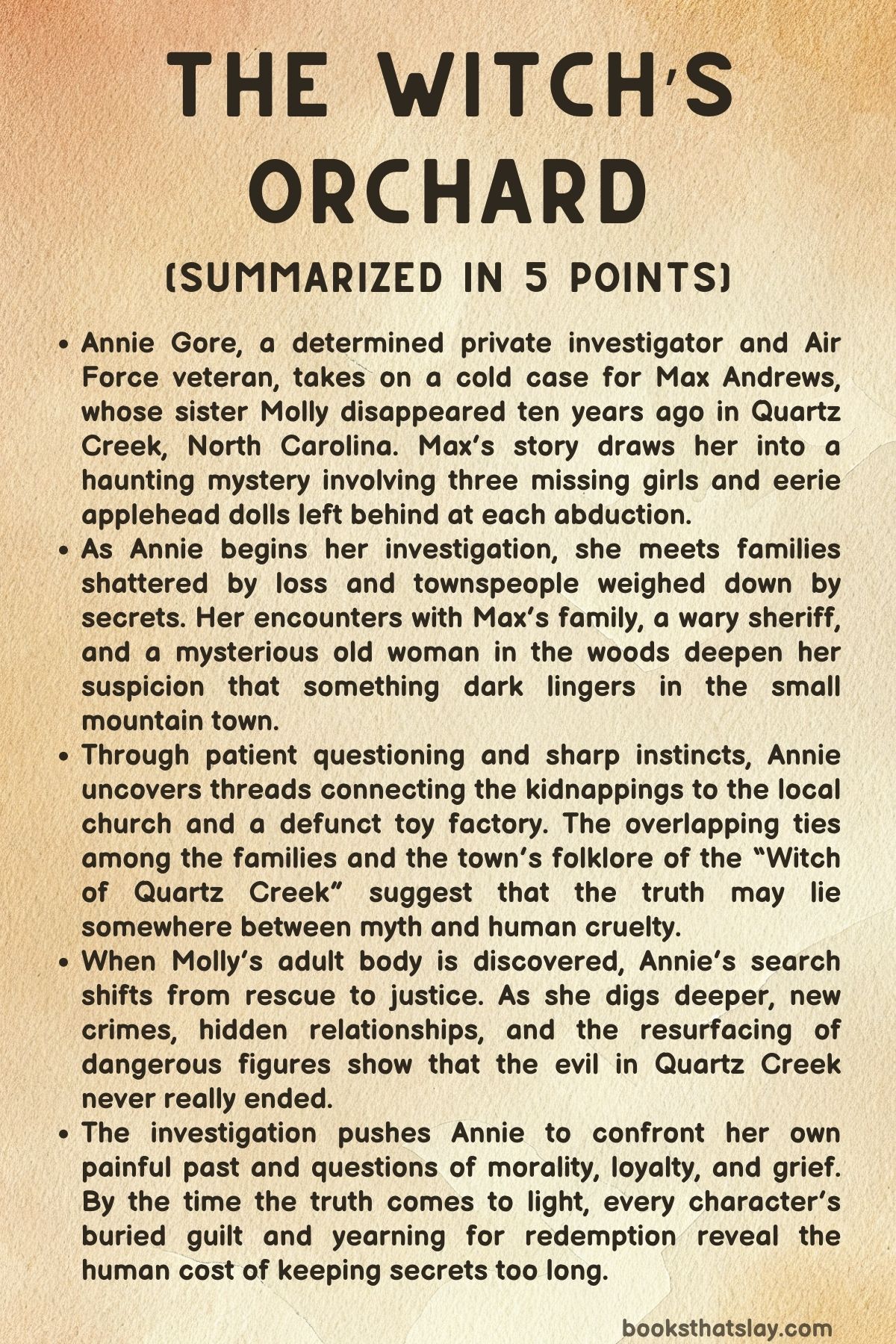

The Witch’s Orchard Summary, Characters and Themes

The Witch’s Orchard by Archer Sullivan is a suspenseful mystery set in the eerie Appalachian town of Quartz Creek, North Carolina. The story follows Annie Gore, an Air Force veteran turned private investigator, who takes on the cold case of Molly Andrews—a young girl who vanished a decade earlier amid whispers of witchcraft and a haunting local legend.

As Annie digs into the past, she uncovers tangled secrets of grief, guilt, and obsession buried within the tight-knit community. What begins as a search for one missing girl turns into an unraveling of multiple abductions, revealing a chilling truth about those living under Quartz Creek’s quiet surface.

Summary

Annie Gore, a private investigator and former Air Force member, is approached by Max Andrews, a young man desperate to find his sister Molly, who was kidnapped ten years ago in Quartz Creek, North Carolina. Molly was one of three girls abducted over one summer, each disappearance marked by a disturbing applehead doll left behind.

One of the missing girls, Olivia Jacobs, was mysteriously returned after two weeks, mute and traumatized, while the other two—Jessica Hoyle and Molly—remained lost. Haunted and determined, Max hires Annie to reopen the case with the savings he’s accumulated over the years.

Annie drives to Quartz Creek, staying in Max’s remote cabin as she begins her investigation. The town is filled with sorrow and suspicion, still haunted by the old legend of “The Witch of Quartz Creek,” a story about a mother who turned into a crow searching for her lost children.

The line between myth and reality blurs as Annie starts her inquiries. Her first encounters—Max’s grief, his mother’s tragic suicide, and the eerie folklore—set the tone for what becomes a dark, unsettling case.

Her investigation leads her to the victims’ families. Kathleen Jacobs, Olivia’s mother, explains how her daughter was taken during a church picnic and returned days later unable to speak.

Jessica Hoyle’s parents, Mandy and Tommy, live in poverty and bitterness, having lost both their daughter and their reputation under suspicion. Mandy, still clinging to faint hope, pleads with Annie to find Jessica too.

The Hoyles’ broken home and the strange mention of Tommy’s cousin, Dwight—who had been nearby the day Molly vanished—give Annie her first tangible lead.

Annie learns that all the kidnapped girls were connected through the local First Baptist Church, where community events often took place. When she visits the church, she’s told by Rebecca Ziegler, the preacher’s wife, that the disappearances all happened during church gatherings.

Rebecca offers to provide attendance lists from that summer. Annie takes note of how everyone in the town seems bound by shared grief and secrets.

While retracing Molly’s last known steps, Annie meets Shiloh, a warm and perceptive baker who once babysat the Andrews children. Shiloh provides insight into the family’s dynamics before the tragedy—how Molly was bright and affectionate, and her mother’s increasing anxiety before the disappearance.

Shiloh introduces Annie to Sheriff Cole Jacobs, Olivia’s uncle, and Deputy AJ Barnes. The sheriff is defensive, while AJ is cooperative and becomes an ally to Annie, warning her that Quartz Creek’s people are all intertwined by family and history.

Annie’s first major discovery comes when she stumbles upon Molly’s body near a mountain gorge. Molly, no longer a child, had somehow survived for years before dying recently.

The revelation devastates Max and reignites the investigation as a homicide case. Soon after, Annie’s cabin is broken into, her files stolen, and Max’s scrapbook of Molly’s life gone.

It’s clear someone wants to stop her from uncovering the truth.

With AJ’s help, Annie begins piecing together patterns in the victims’ lives. The clues point toward the now-condemned DrakeCo Toy Factory, once a major employer in town.

The factory also produced the same model doll found at the kidnapping scenes. When local teenagers mention seeing Tommy and Dwight Hoyle near the abandoned building, Annie investigates.

Inside, she discovers a meth lab and finds Dwight dead, Elaine Hoyle hysterical, and Tommy trapped under burning debris. Annie manages to save Tommy before an explosion destroys the building.

The chaos adds another layer of mystery: how are drugs, dolls, and missing children connected?

Back at the station, Annie and AJ review old police records. They establish a timeline: Jessica was taken first, then Olivia (who was returned), and finally Molly.

The applehead dolls, identical dresses, and connections to the church suggest a ritualistic or obsessive motive rather than random violence. The more Annie learns, the more the community’s façade of piety begins to crack.

Annie’s suspicions turn toward Pastor Bob Ziegler and his wife Rebecca. With help from her old friend Leo, she discovers Bob’s true name and a criminal past that had been quietly erased when he became a preacher.

However, the trail also points to Deena Drake, the Andrews’ former piano teacher, whose husband owned the toy factory that shut down after the kidnappings. When Annie visits Deena’s isolated home, she’s turned away, but learns Deena was one of the last people to see Molly alive.

As tensions build, more details emerge: Sheriff Cole once covered up evidence to protect locals, and former officials like Sheriff Kerridge may have knowingly ignored leads. Annie’s encounters with Susan McKinney—a psychic woman living in the woods accused of witchcraft—add a strange, almost supernatural undercurrent to the case.

The mystery reaches a breaking point when a series of overlapping revelations explode into violence. Mandy Hoyle arrives at Annie’s cabin with Annie’s stolen gun case and Max’s lost casebook, suggesting Tommy was involved in the theft.

Annie confronts Tommy in the hospital, where he rambles about a “witch” who stole his sister Odette years ago, confusing myth with memory. His words hint at a generational pattern of obsession and neglect tied to Quartz Creek’s folklore.

Soon after, Shiloh’s daughter Lucy goes missing. Evidence, including Molly’s toxicology report revealing poison from laurel-infused honey, drives Annie to suspect that the kidnapper may be someone replicating old crimes in ritual fashion.

When Max reports seeing Susan leaving town with a heavy basket, Annie races after her, suspecting the woman might be rescuing or hiding more victims.

Annie tracks the trail to Deena Drake’s property, where she finds chaos: Pastor Bob Ziegler lies shot and bleeding, Deena is tied up, and Lucy is trapped in a hidden panic-room nursery. Jessica Hoyle—alive after all these years—is revealed as Deena’s accomplice and surrogate daughter.

The horrifying truth surfaces: Deena, desperate for children after miscarrying twins, had abducted Jessica and later Olivia, keeping them drugged and conditioned through fear of “the Witch. ” She abducted Molly as well, raising her secretly until the girl grew up and tried to escape.

When Molly ran, Jessica, jealous and unstable, murdered her.

The climactic confrontation ends when Shiloh arrives just in time to rescue Lucy and stop Jessica, who is captured. Deena is arrested, her long deception laid bare: she had manipulated the town’s fears, used local myths to deflect suspicion, and built her twisted family behind locked doors.

Sheriff Jacobs resigns in disgrace, and the FBI uncovers a web of complicity and neglect that had kept the crimes hidden for years.

In the aftermath, the community struggles to heal. Max finally buries Molly, Shiloh returns to her bakery with her daughter, and Mandy leaves her abusive husband to start anew.

Annie departs Quartz Creek, changed by the ordeal. She reconciles briefly with Susan, acknowledging the blurred line between myth and truth.

As she drives away, she reflects on the darkness of human longing—the kind that can turn love into possession—and the ghostly silence left behind by those who vanish.

The Witch’s Orchard ends as both a mystery resolved and a meditation on loss, guilt, and the dangerous power of stories that a community tells to explain the evil within itself.

Characters

Annie Gore

Annie Gore stands as the heart of The Witch’s Orchard, a woman defined by her unyielding resolve and haunted resilience. A private investigator and former Air Force veteran, Annie embodies the archetype of the wounded seeker—someone whose past traumas have hardened her, yet also endowed her with empathy for the broken lives she encounters.

Her independence borders on isolation; she refuses stability, choosing instead a transient life marked by small motels, long drives, and cold cases. Beneath her stoic professionalism lies a scarred soul molded by an abusive childhood, a trauma that allows her to recognize pain in others with unnerving clarity.

Annie’s connection to the case—particularly to Max’s grief and Molly’s disappearance—goes beyond duty. She sees in their tragedy an echo of her own lost innocence and fractured family.

Throughout the novel, she evolves from detached investigator to an emotionally engaged guardian, risking not only her life but her capacity for detachment. Her relationship with AJ softens her cynicism, but it is her determination to seek truth—even when that truth shatters illusions—that defines her essence.

Annie is not simply a detective; she is the embodiment of perseverance against despair, a symbol of confronting one’s ghosts, literal and figurative.

Max Andrews

Max Andrews is both the client and one of the emotional anchors of The Witch’s Orchard. A young man burdened by the long shadow of loss, he represents the enduring wound left by tragedy.

Having lost his sister Molly to a childhood abduction and his mother to suicide, Max has grown into a quietly tragic figure—sensitive, intelligent, yet paralyzed by unresolved grief. His artistry, particularly his crow-themed woodblock prints, mirrors his inner world: beautiful, dark, and yearning for meaning.

Max’s devotion to his sister transcends mere familial love; it becomes a quest for redemption and closure, as if solving the mystery could resurrect the fragments of his broken life. Despite his youth, he displays a stoic maturity and self-awareness, though underneath lies guilt—guilt for surviving, for doing too little, for growing up when Molly could not.

His interactions with Annie reveal his desperate hope and his quiet admiration for her strength. In the end, Max stands as a poignant symbol of how trauma can both destroy and define, leaving behind an indelible mark that no closure can fully erase.

Shiloh Evers

Shiloh Evers, the warm and grounded bakery owner of Quartz Creek, serves as a beacon of light amid the novel’s grim landscapes. Former babysitter to the Andrews children, she represents the maternal compassion that others in the story have lost.

Her bakery, “Shiloh’s Sweet Treats,” is not just a business—it’s a sanctuary, a place of community and kindness in a town drowning in secrets. Yet beneath her nurturing demeanor is quiet strength and courage; she does not shy away from confronting pain or danger, as seen in her unwavering support of Max and her eventual confrontation with Jessica Hoyle.

Shiloh’s bond with Annie grows from cautious acquaintance to genuine friendship, underscoring the importance of trust and sisterhood in the face of darkness. Her role as both caregiver and protector reaches its apex when she saves Lucy and ends Jessica’s violent spree.

Shiloh emerges not as a side character, but as a moral compass—proof that compassion can be as heroic as confrontation.

Jessica Hoyle

Jessica Hoyle is the novel’s most chilling and tragic creation—a lost child turned monster. Abducted as a young girl, she grows up in captivity under Deena Drake’s delusional guardianship, molded by isolation, manipulation, and warped love.

When she resurfaces as an adult, she embodies the horror of innocence corrupted. Jessica’s obsession with preserving beauty and “family” reveals a fractured psyche: part victim, part villain.

Her murder of Molly Andrews and kidnapping of Lucy are not acts of sadism but of delusional preservation—an attempt to recreate a home built on trauma. Through Jessica, The Witch’s Orchard explores how victimhood can metastasize into violence when healing never occurs.

Her confrontation with Annie brings both characters full circle—Annie confronting her past through the mirror of Jessica’s brokenness, and Jessica facing the consequences of the fantasy she built to survive. Jessica’s final scenes blend terror with tragedy, portraying her not merely as evil but as the ultimate casualty of the town’s generational neglect and secrecy.

Deena Drake

Deena Drake is a study in repression, grief, and moral decay. Once a graceful piano teacher and pillar of Quartz Creek society, she conceals beneath her elegance an obsession with motherhood that metastasizes into monstrosity.

After losing her unborn twins and husband, Deena’s grief curdles into denial, leading her to kidnap Jessica Hoyle under the guise of divine providence. Her home becomes a mausoleum of her delusion—a hidden nursery where stolen children replace the ones she lost.

Deena is both victimizer and victim; her actions stem from profound psychological collapse, but her capacity for deceit and manipulation exposes a chilling self-awareness. Her relationship with the corrupt Sheriff Kerridge and her complicity in multiple abductions reveal how evil can flourish under respectability.

Deena’s eventual capture does not bring satisfaction but sorrow; she embodies the perverse intersection of maternal instinct and madness. In her, The Witch’s Orchard finds its darkest truth—that love, when twisted by loss, can become indistinguishable from cruelty.

Sheriff Cole Jacobs

Sheriff Cole Jacobs is a man caught between family, duty, and denial. The uncle of Olivia Jacobs and a figure of authority in a fractured town, he represents institutional failure cloaked in good intentions.

His reluctance to confront the darker undercurrents of Quartz Creek—especially his affair with Deena Drake—reveals the cost of personal compromise in public service. Jacobs is not corrupt in the traditional sense; rather, he is blinded by guilt and emotional entanglement.

His leniency toward Deena and his defensive hostility toward Annie reflect a man terrified of unmasking the rot within his own world. Yet his decision to suspend himself after the truth surfaces shows a spark of conscience—too late to save the victims, but enough to reclaim a fragment of dignity.

Jacobs’s character encapsulates the theme of complicity—the danger of silence and the moral corrosion that festers when truth is inconvenient.

Mandy Hoyle

Mandy Hoyle is the embodiment of endurance in despair. Poor, fragile, and emotionally bruised, she clings to hope even as it devours her sanity.

Her life, overshadowed by her daughter Jessica’s disappearance and her husband’s violence, becomes a slow decay punctuated by faith and desperation. Mandy’s interactions with Annie are heartbreaking—she oscillates between gratitude, guilt, and self-blame, unable to escape the cycle of poverty and trauma.

Her offering of saved money to Annie is an act of both desperation and grace, symbolizing her willingness to sacrifice anything for even a flicker of hope. By the novel’s end, Mandy’s resilience, though born of suffering, transforms into action: she hires lawyers, seeks divorce, and chooses life over limbo.

She is one of the novel’s quiet triumphs—a woman reclaiming agency in a world that has denied her power for too long.

Olivia Jacobs

Olivia Jacobs, the only abducted child to be returned alive, represents the psychological scars left by violence. Rendered mute and mentally withdrawn, Olivia’s silence speaks louder than any testimony.

Through her, the novel captures the incomprehensible horror of trauma experienced too early to be articulated. Her spiral drawings and frightened reactions to the “Witch” legend reveal a fragmented memory trying to process the unprocessable.

Olivia’s existence serves as both clue and warning—living proof of the evil still at large and a haunting reminder of innocence forever broken. She stands as the most tragic survivor, a symbol of the story’s central theme: that some wounds never heal, only adapt.

AJ Barnes

Deputy AJ Barnes serves as both moral support and emotional grounding for Annie. A native of Quartz Creek, AJ bridges the gap between insider and outsider, offering Annie insight into the town’s insular culture while maintaining an openness that contrasts sharply with his superiors.

His compassion, courage, and understated humor make him one of the few sources of light in the narrative. His relationship with Annie evolves from professional camaraderie to tender intimacy, offering her a fleeting reprieve from loneliness.

Yet AJ’s strength lies in his integrity—his willingness to challenge authority, protect the vulnerable, and face danger without bravado. In the end, AJ represents what Quartz Creek might have been if decency had prevailed over denial.

Themes

Grief, Guilt, and the Long After

Grief in The witchs orchard is not a single event but a condition that reorganizes lives, homes, and identities. Max’s family house has been stripped of photographs and emptied of Molly’s room, a physical attempt to cauterize a wound that only deepens the absence.

His mother’s suicide and his father’s retreat into long-haul solitude show grief rippling outward, shifting roles and eroding connection until only function remains. Max himself lives in suspended time; the college acceptance letter and his careful savings for a private investigator mark a young adulthood paused at the moment a little sister vanished.

Kathleen Jacobs’s household presents a different face of mourning: the heavy atmosphere of watchful care around Olivia, who returns alive yet unreachable, turns the family into guardians of a living silence. Mandy Hoyle, trapped in poverty and violence, saves small bills as a talisman against helplessness; her grief is braided with fear, shame, and a stubborn hope that requires her to stay where Jessica could find her.

The investigation becomes a ritual of grief management for the town as well; each interview opens a cupboard of unprocessed sorrow—church leaders keeping confident tones that can’t cover their dread, deputies negotiating between duty and kinship. Annie carries her own freight from childhood abuse and military service, translating loss into relentless motion.

The novel suggests that grief, left unattended, mutates into guilt. Characters seek exchanges that feel like penance—Max hiring Annie, Mandy funding the search, Kathleen warning against reopening wounds—while the actual culprit thrives in that fog.

Grief becomes both the camouflage that hides harm and the engine that finally exposes it when Annie insists that love demands truth even if the truth confirms the worst.

Silence, Voice, and the Ethics of Telling

Silence saturates the story: the stolen voices of girls, the paused speech of adults who know more than they say, and the social quiet that protects reputations. Olivia’s nonverbal life is the most visible instance, but the novel treats her silence as forced containment—first by a drugged return, then by terror layered with a folktale that codes danger as supernatural.

Her spirals and clapping are communication systems others have not learned to read; Annie’s attention reframes Olivia from passive victim to witness whose language was never given room. Institutional silence operates in parallel.

The first FBI lead’s brutality against a terrified child is hushed through bureaucratic replacement; Sheriff Jacobs’s conflict of interest with Deena becomes a fog of partial disclosures; the church’s closed language of confidentiality shields Pastor Bob at crucial moments. Even the landscape is tuned to echo rather than articulate—the stone circle amplifies sound while obscuring source, a metaphor for rumors that grow louder without clarifying truth.

Against this, the book stages acts of speaking that carry moral weight: Max arriving with a scrapbook, Mandy handing over hard-earned cash, Shiloh telling different versions of the witch story, AJ risking his job to share files. Annie’s method is to make people narrate and to notice gaps, treating omissions as data.

When Jessica finally speaks in the hospital, her confession exposes how storytelling can be weaponized; she rehearsed a life script inside Deena’s curated nursery and decided to protect that narrative with murder. The novel argues that voice is not merely sound but accountability.

Giving testimony restores personhood to the missing, while withholding truth becomes complicity. In the final movements, speech—accurate, documented, and courageous—reconstitutes a communal memory that institutions had allowed to fray.

Community Complicity and Institutional Failure

The setting constructs a town where everyone is someone’s cousin, student, parishioner, or old friend, a web that confers belonging and breeds impunity. The witchs orchard maps how overlapping loyalties blunt vigilance: a sheriff related to a victim, a preacher wrapped in church privilege, a former factory owner turned piano teacher whose status buys trust.

The result is a law-and-order façade that repeatedly misdirects attention toward convenient suspects—the poor Hoyles, the odd woman in the woods—while overlooking polished living rooms and educated criminals. The closed loop of authority is decisive.

Sheriff Kerridge once rationalized removal of a child from a “bad” home by permitting an illegal abduction; when threatened by exposure, he was poisoned and the truth buried under respectability. Later, Sheriff Jacobs’s romantic entanglement compromises objectivity, and his initial hostility to Annie shows a reflex to defend insiders and control the narrative.

Even federal intervention fails when an agent assaults a child witness; the system replaces a person but not the culture that allowed it. The church, supposedly a moral center, practices image management: privacy rhetoric, fall festivals, and pastoral visits that function as access corridors rather than safeguards.

The town’s appetite for explanations settles on the supernatural witch because it requires no names, no paperwork, no prosecutions. Standing outside those ties, Annie, Leo, and to a degree AJ create a counter-institution of inquiry where evidence, not affiliations, decides guilt.

The book’s critique is not that communities are inherently corrupt but that unquestioned familiarity becomes a shield for predators. Real protection arises when relationships are matched with transparent procedures, when every role—sheriff, preacher, teacher—is answerable to facts rather than kinship.

Desire, Control, and the Fantasy of the Perfect Family

Deena’s arc exposes a form of predation wrapped in domestic longing. After miscarriage and widowhood, she pursues a fantasy in which motherhood is not nurtured but acquired, outfitted, and secluded.

The “poppet” readings, the velvet dresses, the secret nursery, and the curated lessons transform children into décor that reflects an aesthetic rather than acknowledges autonomy. Desire here is about control: remove parents, rename routines, invent rituals, and the household becomes a stage where the adult never risks loss again.

The plan requires silence drugs, a complicit or compromised official, and a community willing to mistake elegance for virtue. Deena’s yearning is not portrayed as monstrous by itself; what damns it is the willingness to override consent and to rationalize abduction as rescue from less refined lives.

Jessica’s evolution inside that setting reveals the downstream effect: a child trained to see affection as possession, to equate beauty and order with survival, and to act decisively to protect the arrangement. Her decision to kill Molly, framed as preserving a “pretty” life, is the logic of the curated home taken to its lethal end.

The book questions cultural scripts that sanctify motherhood without interrogating power. It shows how the language of care—lessons, safety, a warm bed—can become a cover for capture when the child’s will is not part of the definition.

Annie’s intervention restores a model where guardianship is accountable and specific: call 911, keep records, ask for warrants, return property, tell relatives the truth. Shiloh’s open kitchen, Max’s art, and Mandy’s stubborn saving, by contrast, depict care as labor and risk rather than display, insisting that families are made by consent and continuity, not by possession.

Folklore, Fear, and the Uses of Myth

The witch story coils through the plot as both a cultural artifact and a tactical instrument. Residents pass along versions that shift details—daughters turned to birds, a mother bargaining for apples, a crow’s cry in the gorge—until the tale functions as a shared map of dread.

In The witchs orchard, myth is not merely background color; it is an operating system for the town’s interpretive habits. When children vanish, the legend offers a ready explanation that is emotionally satisfying and operationally useless.

It channels fear toward the forest and away from the piano teacher’s staircase, away from the church’s volunteer lists, away from the retired sheriff’s decisions. Deena and Jessica exploit this appetite by staging signs that fit the tale: applehead dolls, ritualistic touches, and whispers about stone circles.

Even those who reject superstition end up speaking in its vocabulary because it organizes the community’s memory. Annie treats the myth anthropologically, asking who benefits when a story absorbs blame.

Her interviews show the legend mutating depending on the teller’s position—workers at the factory hear of transformations, church leaders emphasize cautionary morals, Shiloh’s version centers hunger and bargaining. This variability exposes the story’s function as social technology.

It justifies suspicion of outsiders like Susan while screening insiders. The eventual solution does not abolish the folktale; it reassigns it to its rightful shelf as metaphor rather than evidence.

The forest can still be eerie and crows can still announce stormlight, but the book insists that danger traveled in cars, wore tasteful sweaters, and signed lesson checks. Myth is reclaimed as culture when it no longer dictates whom to accuse.

Class, Reputation, and Moral Credibility

Class defines who is believed, who is surveilled, and who gets the benefit of the doubt. The Hoyles’ poverty and Tommy’s drinking mark them as default suspects from the outset, an assumption that partly shields the real abductor.

Police energy pools around the shabby house at the end of the muddy road, while the mountaintop home of a factory family receives reverent courtesy. Mandy’s crumbling porch becomes a stage for derision even as she performs every gesture of responsibility available to her—work, savings, childcare programs—while Deena’s carefully arranged rooms are mistaken for proof of moral order.

The same bias operates within institutions: a nurse mother’s warning is treated as obstruction, a preacher’s evasions as pastoral discretion, a mechanic aunt’s blunt counsel as cynicism. Reputation becomes soft armor that allows middle-class actors to redefine events.

Sheriff Kerridge’s choice to “rescue” a child from a poor home by laundering a kidnapping would have been unthinkable if the receiving household lacked prestige. The book’s meth-lab sequence intensifies the contrast: explosive chaos in a condemned factory is read as endemic moral failure, yet it sits atop a supply chain of money that originated in blackmail flowing from an elegant address.

Annie’s practice is to audit credibility through behavior, not biography. Who calls emergency services?

Who hands over stolen items without bargaining? Who tolerates scrutiny of their timeline?

By the end, moral credibility is redistributed. Mandy’s steadiness and Shiloh’s reliability register as civic assets; Max’s art reveals a disciplined interior life; AJ’s rule-bending aligns with public good.

The fall of figures who hid behind polish exposes class as a performance that can be purchased, while character must be shown.

Trauma, Agency, and the Work of Healing

The novel traces how trauma narrows choices and how agency reopens them through specific acts. Annie’s history of domestic violence gives her a pragmatic ethic: protect the vulnerable, keep receipts, move your body toward the fire when others freeze.

Her Air Force discipline and the battered-child past are not glamorized; they fuel hypervigilance, thrift, and a stubborn refusal to outsource responsibility to institutions that might fail. Max’s agency is quieter but no less deliberate: years of saving, curation of a casebook, and the courage to hire help rather than collapse into bitterness.

Olivia’s agency looks different still. Though she does not speak, her drawings and routines carry testimony; the community’s failure was not that she had no voice but that they did not learn its grammar.

Mandy’s turning point arrives when she reclaims her material world—money hidden in a roll, a car reclaimed from misuse, a decision to move with her boys—small choices that add up to safety. AJ’s choice to share files is a professional risk that reorients an investigation mired in conflicts of interest.

Even Shiloh’s hospitality functions as harm reduction; a steady meal and a steady friend create a base from which courage becomes thinkable. Healing in The witchs orchard is not a future promise but a series of present tense actions: telling the truth about the dead, returning stolen property, arresting the right people, and planning funerals that name what happened.

The final departures—Annie on the road, Mandy relocating, Shiloh reopening the bakery—register not as escape but as motion restored. The past is acknowledged, the ledger updated, and the living given back their calendars.

Objects, Landscapes, and the Material Signs of Evil

Physical things carry meaning and motive throughout the book. Applehead dolls, handmade and grotesque, operate as calling cards that turn fear into a collectible; the town’s fixation on them keeps eyes on the uncanny and away from human hands tying knots and forging keys.

The velvet dresses and the nursery’s twin beds objectify childhood as display, converting affection into arrangement. Max’s woodcuts of crows, by contrast, transform rage and love into craft, insisting that representation can dignify rather than consume.

The stone circle with quartz that returns sound strangely is a landscape metaphor for investigation: inputs grow louder without getting clearer, and only placement—where you stand—produces usable signal. Annie’s Datsun “Honey” embodies survival: a machine patched, fueled, and kept running by a network of kin and grit, a counter-image to the late-model vehicles bought with meth money and hush funds.

The old factory is the most revealing object in the setting. Once a site that manufactured dolls, it decays into a lab that cooks drugs, and finally into a burning confession of the town’s neglect; in each phase, it converts bodies into products—children into poppets, labor into profit, addicts into collateral.

Even documents matter: lists from the church, letters from colleges, scrapbooks of clippings, and case files on a laptop. Whoever controls the paper trail controls the memory of events.

In the end, objects are restored to proper use. A gun protects a child rather than enforcing a fantasy; a scrapbook becomes evidence rather than a shrine; a crow print becomes an artist’s signature rather than a symptom of grief.

The novel teaches readers to read things as witnesses, not ornaments, and to trust landscapes and artifacts only after asking who placed them and to what end.