We Are All Guilty Here Summary, Characters and Themes

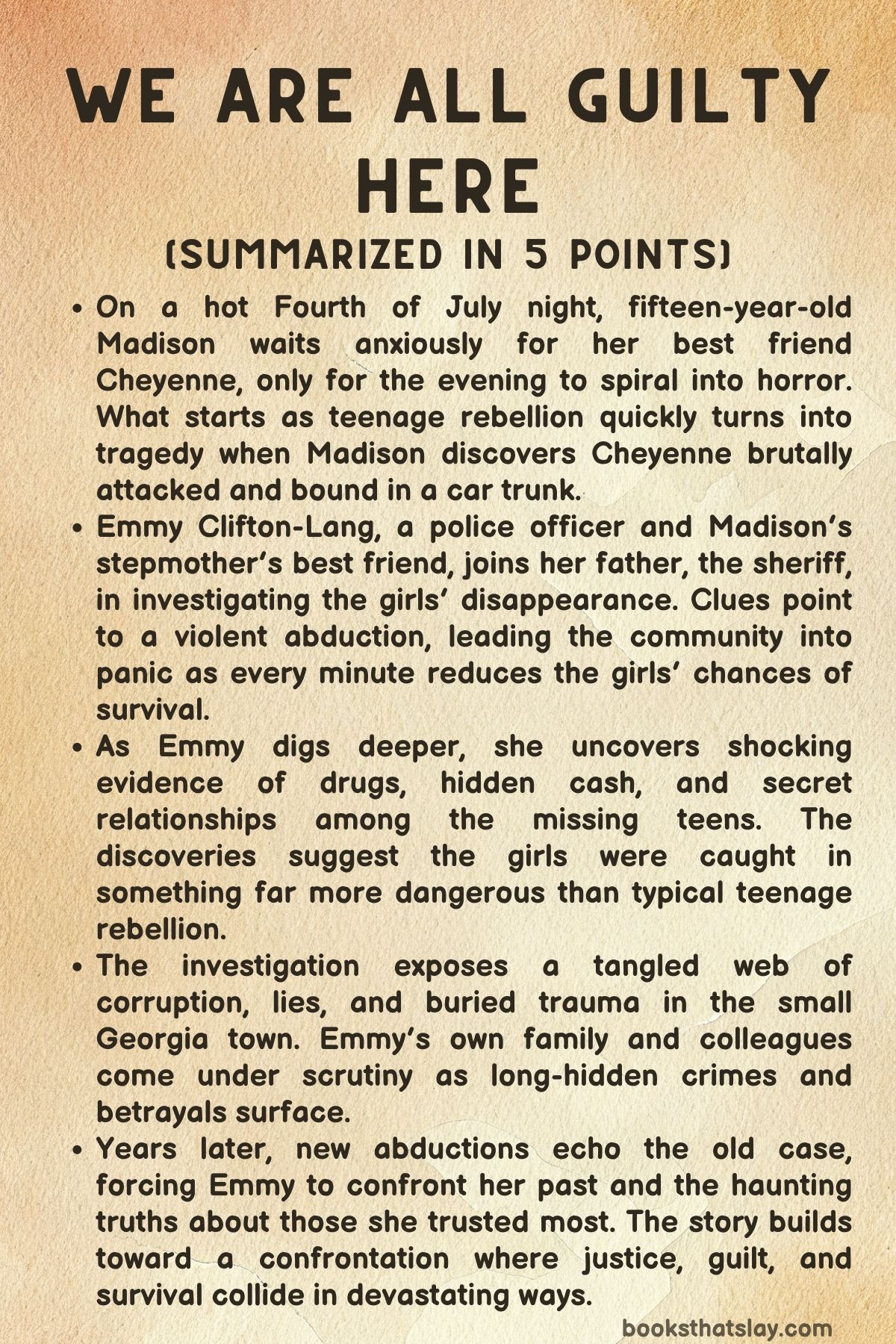

We Are All Guilty Here by Karin Slaughter is a dark, layered crime thriller that examines the ripple effects of buried secrets, moral compromise, and systemic corruption within a small Georgia town. The story begins with the disappearance of two teenage girls during a Fourth of July celebration and unfolds into a chilling investigation that spans decades.

Slaughter explores the intertwined fates of families, law enforcement, and survivors haunted by their own guilt. With themes of power, justice, and generational trauma, the novel delves into how the sins of the past return to claim the present, revealing that guilt and innocence are rarely clear-cut.

Summary

The story opens on a humid Fourth of July evening in North Falls, Georgia. Fifteen-year-old Madison Dalrymple waits under an oak tree for her best friend, Cheyenne Baker.

The two girls plan to steal Cheyenne’s father’s car and take a joyride during the fireworks—part of a larger dream of running away to Atlanta. Madison’s stepmother, Hannah, and her father are nearby, but she avoids them, resentful of their disregard for her late mother’s memory.

As the minutes pass, Cheyenne’s absence begins to worry Madison.

Emmy Clifton-Lang, a police officer and Hannah’s best friend, stops to chat with Madison, warning her subtly that Cheyenne might be a bad influence. Madison, defensive and angry, brushes her off.

As the fireworks explode overhead, Madison finally spots a car driving toward her—its headlights off, its path erratic. Relieved, she assumes it’s Cheyenne.

But when she opens the trunk, she discovers Cheyenne bound, gagged, and bloodied. A shadowy man appears, and Madison’s world goes black.

After the fireworks end, Emmy and her father, Sheriff Gerald Clifton, investigate the chaos of departing crowds. They discover Madison’s mangled bicycle under an SUV and a pool of blood nearby.

The scene suggests a violent abduction. Emmy recalls her brief conversation with Madison earlier, realizing she may have been the last to see her alive.

As the evidence piles up—two missing girls, two bikes, blood, and tire tracks—Gerald grimly announces a kidnapping. The small-town celebration transforms into a crime scene.

Emmy and Gerald visit the Bakers, where panic and accusations erupt. Ruth Baker, Cheyenne’s mother, blames Madison for corrupting her daughter, while Felix Baker admits Cheyenne had become rebellious and secretive.

When Emmy searches Cheyenne’s room, she uncovers drugs, cash, and a suggestive photo of Cheyenne and Madison. Hidden further are bags of cocaine, ecstasy, and birth control pills, hinting at a dangerous double life.

Cheyenne’s younger sister Pamela reveals that Cheyenne had a boyfriend named Jack.

Emmy and Gerald question Jack Whitlock, the son of the town pediatrician. Jack describes Cheyenne and Madison as manipulative bullies who sold drugs and may have been connected to an older man known only as “the Perv,” who supplied teens with drugs near the Falls.

Emmy and Gerald begin to suspect the kidnapping may be linked to sexual exploitation or trafficking. They contact the FBI and expand the search.

At Madison’s home, Hannah collapses when Emmy delivers the news. Their friendship fractures as Hannah blames Emmy for ignoring Madison before the fireworks.

Emmy’s guilt deepens, compounded by her own marital strife with her abusive husband, Jonah. Later, Emmy’s niece Kaitlynn confides that Cheyenne once bragged about an older man paying her for sex, confirming their suspicions about grooming and exploitation.

When blood tests confirm that Cheyenne’s blood was found at the scene but Madison’s was not, hope flickers that at least one girl may still be alive.

Years later, Emmy stands at her father’s funeral, now burdened by new tragedies. Gerald has been murdered during a police confrontation, and Emmy’s personal life is in ruins.

At the service, a mysterious woman introduces herself as Jude Archer—later revealed to be Martha, Emmy’s long-lost sister who was believed dead. Jude is now an FBI profiler, returning to North Falls to help solve the disappearance of another young girl, Paisley Walker, whose abduction mirrors that of Madison and Cheyenne years before.

As Emmy, now acting sheriff, works with Jude and the FBI, they uncover unsettling patterns connecting past and present crimes. Jude interrogates Paisley’s father, discovering his infidelity and ties to a mysterious woman named Trixie.

Meanwhile, Emmy and Jude’s strained reunion exposes buried family secrets—especially surrounding their father’s alcoholism and their mother Myrna’s decline into dementia. The investigation reveals how trauma has fractured their family across generations.

During the ongoing case, Emmy discovers inconsistencies in old files stored by Virgil Ingram, a retired deputy and once Gerald’s trusted colleague. While reviewing the evidence, she notices tampered phone records and hidden items—jewelry belonging to past victims, trophies of murder.

The horror deepens when she finds a phone containing video evidence implicating Virgil himself in the abductions and murders of Cheyenne and Madison. She realizes he not only covered up the crimes but was the perpetrator.

Virgil catches Emmy in the act. Armed and unrepentant, he confesses his role in the killings, recounting how he and Walton Huntsinger abducted the girls after Cheyenne filmed them during a sexual encounter.

The men tortured and killed both girls, then staged evidence to mislead investigators. When Virgil raises his gun, Emmy shoots him dead.

Trembling, she informs her son Cole that Virgil—their family friend and mentor—was the monster they had been hunting all along.

Driven by instinct, Emmy follows a final lead to Virgil’s barn, where she discovers Paisley Walker alive but gravely injured. Her rescue brings both relief and sorrow: though Paisley will survive, the revelation of Virgil’s crimes shatters the community’s faith in its protectors.

In the aftermath, Jude interrogates Walton Huntsinger, who confesses to the full extent of his and Virgil’s depravity. They had exploited and murdered multiple girls over the years, framing others to maintain their image of authority.

Emmy, haunted but resolute, oversees the cleanup—approving plea deals, protecting innocent families, and trying to rebuild trust in law enforcement.

A final revelation surfaces when Emmy reviews footage from the day Gerald was killed. The video shows that Hannah, Madison’s mother, accidentally fired the fatal shot while struggling with her husband, Paul.

Choosing compassion over truth, Emmy deletes the video, sparing Hannah from further pain.

In the closing scenes, Jude visits their mother, who is lost to dementia. The sisters reflect on the lies that shaped their family—the hidden pregnancy that separated them, the forgiveness that came too late, and the cycle of secrecy that defines their lives.

When Emmy invites Jude to join a family potluck, it marks the beginning of fragile reconciliation.

We Are All Guilty Here ends with justice served but innocence long lost. Emmy and Jude stand as survivors of both familial and communal corruption, carrying the burden of truth in a town built on silence.

The novel closes not with triumph, but with endurance—acknowledging that guilt binds everyone, and redemption comes only through facing what has long been buried.

Characters

Madison Dalrymple

Madison Dalrymple is a fifteen-year-old girl whose vulnerability, rebellion, and longing for emotional connection drive much of We Are All Guilty Here. Still mourning her deceased mother and feeling alienated from her father and stepmother, Madison seeks validation through her friendship with Cheyenne Baker.

Beneath her defiant exterior lies a sensitive teenager desperate to be seen and understood. Her decision to rebel—stealing a car, drinking, and planning to run away—stems less from delinquency and more from the suffocating loneliness she experiences within her fractured family.

Madison’s arc reflects the tragedy of youthful idealism colliding with the dark undercurrents of adult corruption. She becomes an innocent casualty in a web of exploitation far beyond her comprehension, embodying the vulnerability of adolescence in a morally decaying community.

Cheyenne Baker

Cheyenne Baker is the catalyst for much of the novel’s chaos—a magnetic yet deeply troubled girl who represents both rebellion and victimhood. Outwardly confident and manipulative, Cheyenne masks deep insecurities rooted in a controlling family and a need for independence.

Her involvement in drugs, sexual manipulation, and blackmail reveals how easily a teenager can be groomed and corrupted by adults in positions of power. Cheyenne’s duality—both victim and agent of chaos—drives the reader’s moral unease.

She is at once sympathetic and culpable, her flirtation with danger culminating in her tragic abduction and murder. Through Cheyenne, Karin Slaughter exposes the brutal intersection of teenage recklessness, systemic neglect, and predatory exploitation.

Emmy Clifton-Lang

Emmy Clifton-Lang is a complex embodiment of guilt, resilience, and justice. As both a police officer and a flawed human being, she carries the weight of personal failure and professional responsibility.

Her early indifference to Madison’s distress and her preoccupation with her failing marriage set the tone for her deep internal torment. Throughout the narrative, Emmy’s journey becomes one of painful reckoning—confronting her own complicity in a system that failed to protect the innocent.

Her eventual discovery of the real perpetrators and her killing of Virgil Ingram transform her from a passive observer into a woman who reclaims moral agency through decisive, if traumatic, action. Emmy’s layered characterization—dutiful yet haunted, strong yet broken—anchors the emotional core of the story.

Sheriff Gerald Clifton

Gerald Clifton, Emmy’s father and the town sheriff, represents both moral authority and generational burden. He is a principled yet weary lawman whose career has been shaped by compromise, secrets, and the unspoken rot within his department.

Gerald’s paternal instincts conflict with his professional obligations, especially as the investigation into the girls’ disappearance unfolds. His eventual death serves as both a personal and symbolic loss—the passing of a flawed but decent man amid a landscape of corruption.

Gerald’s relationship with Emmy is tender yet strained, revealing the human cost of lives devoted to duty over emotional honesty.

Hannah Dalrymple

Hannah Dalrymple, Madison’s stepmother and Emmy’s best friend, is a portrait of maternal inadequacy masked by good intentions. Her relationship with Madison is fraught with tension—she tries to assert authority while never truly filling the emotional void left by Madison’s biological mother.

Hannah’s interactions with Emmy reveal a volatile mixture of dependence and resentment, culminating in a heartbreaking confrontation that severs their friendship. Her inadvertent role in Gerald’s death later underscores the theme of collective guilt.

Hannah’s tragedy lies in her inability to reconcile love, jealousy, and fear, symbolizing how personal failures echo through the broader cycle of violence and loss.

Felix and Ruth Baker

Felix and Ruth Baker, Cheyenne’s parents, serve as a study in repression and denial. Felix, detached and guilt-ridden, represents the quiet failure of patriarchal authority, while Ruth’s hysteria and moral rigidity expose her desperation to maintain control in a collapsing family dynamic.

Their home—tidy yet lifeless—mirrors their emotional disconnection from Cheyenne. Ruth’s insistence on blaming Madison rather than confronting her daughter’s pain reflects the community’s larger tendency to vilify victims rather than address systemic rot.

Through the Bakers, the novel critiques parental blindness and the societal complacency that allows evil to thrive.

Jude Archer (Martha Clifton)

Jude Archer, formerly Martha Clifton, is the resurrected ghost of the Clifton family—a woman who escaped her past only to be drawn back into its decay. Now an FBI agent and criminal psychologist, Jude embodies reinvention and trauma recovery.

Her return forces long-buried family secrets to surface, including her own hidden motherhood. Jude’s analytical detachment contrasts sharply with Emmy’s emotional volatility, yet both sisters share a deep moral intelligence and capacity for pain.

Through Jude, Slaughter explores survival as both a psychological and moral act—how one’s past, no matter how carefully buried, inevitably demands reckoning.

Virgil Ingram

Virgil Ingram, once a trusted deputy, emerges as the embodiment of evil concealed within the façade of respectability. His dual life—mentor and murderer—illustrates the insidious nature of power abuse.

By manipulating investigations and grooming young girls, Virgil represents institutional corruption at its most intimate and horrifying. His calculated cruelty and narcissism render him one of Slaughter’s most chilling villains.

Yet, his familiarity with Emmy and Gerald adds a tragic layer—the betrayal of a man once seen as family. His downfall at Emmy’s hands signifies both justice and the psychological toll of confronting moral darkness.

Walton Huntsinger

Walton Huntsinger functions as Virgil’s accomplice and a cautionary figure in moral cowardice. Unlike Virgil’s confident sadism, Walton’s weakness drives him to follow rather than lead.

His confession near the end exposes not only his crimes but also the broader network of misogyny and complicity that sustains such evil. Walton’s character reinforces the novel’s assertion that guilt is communal—borne not only by monsters but also by those who remain silent in their presence.

Cole Lang

Cole Lang, Emmy’s son, provides a glimmer of hope amid generational trauma. Intelligent, perceptive, and emotionally grounded, Cole acts as Emmy’s moral compass.

His presence forces her to remain tethered to humanity despite the overwhelming darkness surrounding her. Through their bond, Slaughter contrasts cycles of abuse and recovery, suggesting that love—imperfect but persistent—remains the only force capable of breaking the chain of inherited guilt.

Jonah Lang

Jonah Lang, Emmy’s estranged and abusive ex-husband, personifies toxic masculinity and emotional decay. His alcoholism and cruelty serve as a mirror to Emmy’s self-destructive tendencies.

Their volatile relationship reveals how personal trauma bleeds into professional failure. Jonah’s presence haunts Emmy throughout the novel, a constant reminder of the choices that shaped her—and the resilience required to escape them.

Paisley Walker

Paisley Walker is both a victim and a symbol of survival. Her abduction parallels that of Madison and Cheyenne, but unlike them, she is saved, embodying the novel’s fragile hope for redemption.

Her survival gives meaning to Emmy’s relentless pursuit of justice and underscores the cyclical nature of violence against girls in North Falls. Through Paisley, Slaughter closes the narrative loop, reminding readers that salvation often comes at the highest emotional cost.

Themes

Guilt and Accountability

Guilt in We Are All Guilty Here operates as both a psychological force and a societal commentary, shaping nearly every character’s journey. It is not confined to the criminals who commit acts of violence but spreads across an entire community complicit in silence, neglect, and moral blindness.

Emmy Clifton-Lang’s burden of guilt becomes the emotional core of the narrative. Her failure to heed Madison’s need for guidance before the abduction ignites a chain of remorse that influences her later actions, particularly her relentless pursuit of justice.

The title itself reflects this pervasive culpability—every person, from the victims’ parents to law enforcement, shares in the moral weight of the tragedy. Karin Slaughter presents guilt as an enduring consequence of inaction.

Emmy’s guilt transforms from paralyzing self-reproach into determination, showing how confronting one’s failures can lead to redemption. Yet, the novel refuses to grant easy absolution.

Hannah’s concealed role in the sheriff’s death and Emmy’s choice to destroy evidence to protect her underscore the moral complexity of justice and forgiveness. The community’s collective guilt mirrors real-world societal failures—how apathy, gossip, and the need to maintain appearances can allow evil to flourish unnoticed.

The final interactions between Emmy and Jude reveal that guilt, while corrosive, also becomes a connective tissue—forcing recognition of shared humanity and the necessity of compassion even amid profound wrongdoing.

Corruption and Abuse of Power

The novel exposes the devastating consequences of unchecked authority through its portrayal of Virgil Ingram, a trusted deputy who manipulates the justice system to hide his crimes. His dual identity—as protector and predator—embodies institutional rot, demonstrating how power, when shielded by loyalty and hierarchy, enables monstrous acts.

Karin Slaughter crafts a chilling examination of how such corruption festers not because of a single man’s evil but because of an entire system’s complicity. Virgil’s colleagues, blinded by familiarity, overlook procedural anomalies, missing signs that could have saved lives.

The story suggests that evil is sustained by institutional inertia—the failure to question, to investigate, or to imagine betrayal within one’s ranks. Emmy’s discovery of Virgil’s trophies and falsified records serves as the ultimate betrayal, shattering her belief in law enforcement as a moral refuge.

Yet her act of killing Virgil also marks a reclamation of integrity, albeit one stained by blood. The abuse of power extends beyond Virgil: from patriarchal control in families to emotional dominance within marriages, authority is constantly depicted as something easily corrupted.

The novel’s portrayal of power thus becomes cyclical—those who suffer under it may perpetuate it, and only through conscious moral reckoning can that cycle be broken.

Family and the Complexity of Bonds

Family in We Are All Guilty Here is portrayed as both sanctuary and prison. The narrative reveals how familial love, when bound by secrecy, denial, and repression, mutates into a source of pain.

Emmy’s relationship with her father, Sheriff Gerald Clifton, anchors this theme. His death forces her to confront the ambivalence of their bond—his moral rigidity, his paternal affection, and his role in shaping her identity as both daughter and law enforcer.

Similarly, the reemergence of Jude (formerly Martha) exposes the fractures of a family eroded by lies and forced distance. Their reunion is not marked by warmth but by confrontation with the past, showing how unresolved trauma corrodes generations.

Slaughter’s depiction of family extends beyond bloodlines: Madison and Cheyenne’s friendship functions as a chosen family that promises freedom but leads to tragedy. Parents like Hannah and Felix, trapped in their guilt and moral blindness, fail to see the warning signs in their daughters’ lives, highlighting how emotional neglect can be as destructive as overt abuse.

By the novel’s end, the fragile reconciliation between Emmy and Jude offers a glimmer of restoration—not through forgiveness alone, but through the acknowledgment of shared wounds. Family here becomes less about unconditional love and more about the courage to face painful truths together.

Trauma and Survival

Trauma in the novel is omnipresent, shaping both victims and survivors across time. Slaughter portrays trauma not as a single event but as an evolving condition that defines identity and moral choices.

Emmy’s psyche bears the cumulative weight of professional exposure to violence, personal loss, and moral compromise. Her numb composure after killing Virgil represents the psychological cost of survival—how trauma often disguises itself as strength.

Jude’s survival story further complicates this theme: her escape from a violent past and reinvention as an FBI agent reflect both resilience and suppression. When she reunites with Emmy, her composure cracks, revealing that survival often demands emotional self-erasure.

The young victims—Cheyenne, Madison, and later Paisley—embody the physical and psychological brutality inflicted upon the powerless. Yet through Emmy’s final act of saving Paisley, Slaughter offers a form of catharsis: survival as both resistance and rebirth.

The dialogue between Emmy and Jude in the closing chapters reframes trauma as an addiction—something that never disappears but can be managed through honesty and human connection. By treating trauma as cyclical and communal, rather than isolated and personal, the novel underscores that healing requires confronting not only individual pain but also the systems and silences that perpetuate it.

The Illusion of Innocence

Throughout We Are All Guilty Here, innocence is portrayed as a fragile construct—socially imposed, easily shattered, and often complicit in masking evil. The idyllic small-town setting operates as a façade of moral purity beneath which exploitation and hypocrisy thrive.

Madison and Cheyenne’s youthful rebellion—initially framed as ordinary teenage defiance—becomes a lens through which Slaughter examines the dangers of idealizing innocence. The girls’ choices, influenced by peer pressure and predatory adults, expose the blurred boundaries between victimhood and agency.

Similarly, figures like Virgil exploit the community’s trust, weaponizing the illusion of decency to conceal depravity. Emmy’s own moral journey dismantles the myth of innocence as a protective force; her decision to kill Virgil, to destroy evidence for Hannah, and to conceal truths demonstrates that survival often demands moral compromise.

The narrative rejects the binary of good and evil, replacing it with a more uncomfortable reality—that innocence is neither inherent nor enduring but shaped by circumstance, power, and fear. By the end, the town’s collective awakening mirrors the reader’s: innocence was never purity but ignorance, and the true path to redemption lies not in reclaiming it but in confronting its falsity.