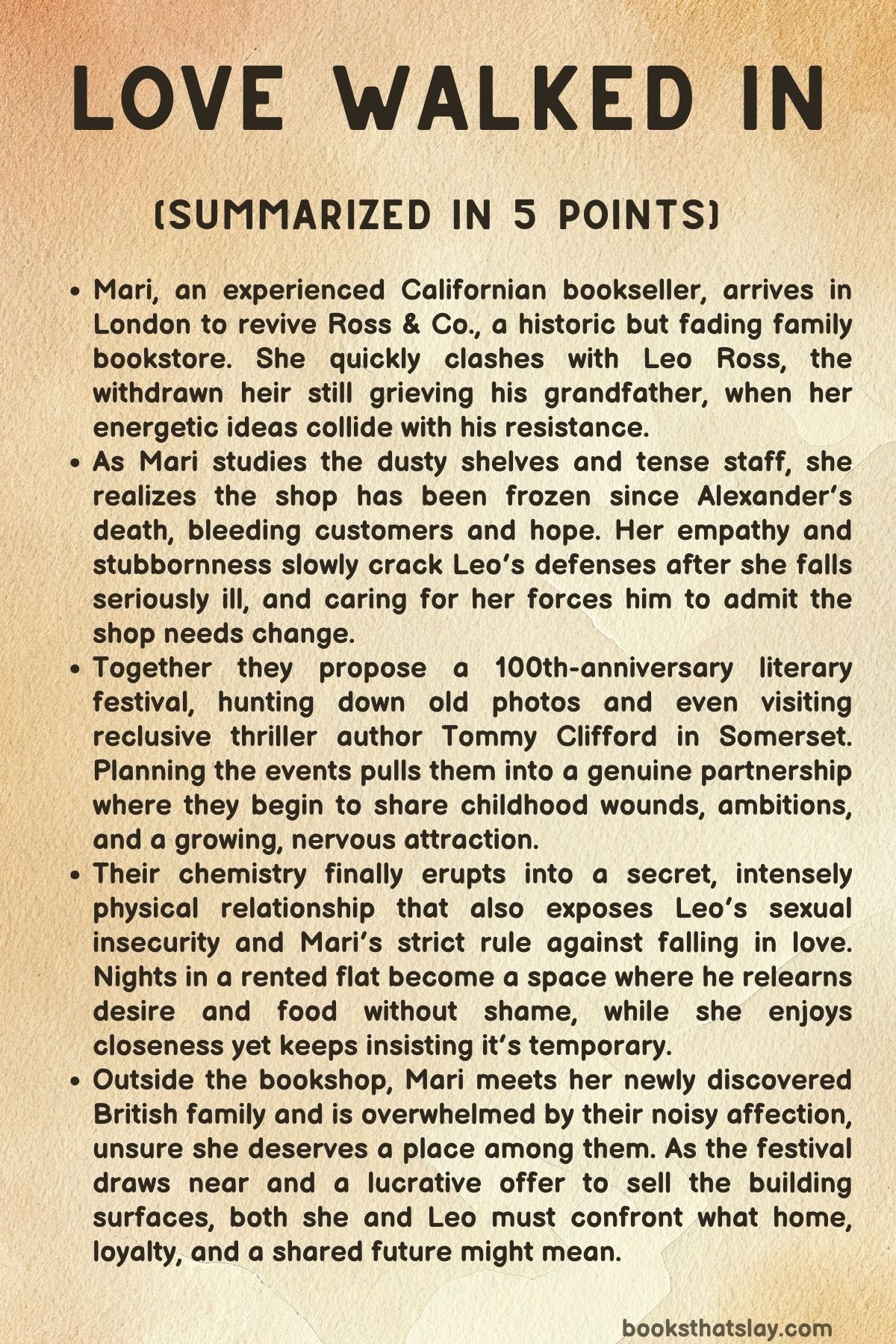

Love Walked In Summary, Characters and Themes

Love Walked In by Sarah Chamberlain is a contemporary novel about transformation, connection, and the messy courage it takes to start again. The story follows Mari, an American bookseller determined to revive a fading London bookshop, and Leo, the grieving heir trying and failing to hold the place together.

What begins as a clash of tempers grows into a slow, intimate partnership that challenges both of them to confront loss, identity, fear, and desire. Through family secrets, community rebuilding, and a romance neither expects, the novel explores what it means to find belonging in places—and people—you never planned to love.

Summary

Mari arrives in London ready to save Ross & Co. , a once-beloved independent shop now dusty, poorly managed, and half-asleep.

She is optimistic, trained, and eager to work, but her first encounter with Leo Ross—sketching behind the counter, drained and irritable—sets the tone for immediate friction. He dismisses her enthusiasm, mocks her genre preferences, and resents her presence.

Only after realizing she is the consultant the family expected does his sour mood deepen further. Upstairs, Mari meets Judith, Leo’s warm step-grandmother, and David, Leo’s father, who openly wants out of the book business.

Mari is forthright about the store’s problems, and though she accidentally touches on sore subjects around the late Alexander Ross, the family’s beloved patriarch, Judith insists Mari will work closely with Leo over the next three months.

Leo struggles privately with depression, insomnia, and grief. His friend Vinay teases him about Mari while nudging him to consider selling the valuable building to developers.

Leo refuses. Meanwhile, Mari is settling into her freezing attic room above the shop and meeting the staff.

Graham, the affable nonfiction buyer, and Catriona, the sharp fiction buyer, explain how the store drifted after Alexander’s death. Leo, unable to let go of the past, has kept everything stagnant.

Staff morale, sales, and daily energy have dwindled.

Mari tries to help customers anyway, despite Leo’s insistence that friendliness annoys Brits. A failed interaction embarrasses her and fuels more conflict.

The next day she starts clearing out old stock and preparing returns, essential work the shop has neglected. Leo interprets this as disrespect for his grandfather’s legacy.

Their argument escalates until he lashes out crudely. Mari storms out into the cold, shaken but unwilling to quit.

Leo immediately regrets his outburst. The next morning he learns from Graham that Mari is sick in her room.

When an elderly customer praises a book Mari recommended, Leo finally recognizes her skill. Worried about her silence upstairs, he checks on her and finds her feverish.

Despite their conflict, he takes responsibility for her care—calling the NHS helpline, buying medicine, feeding her, and keeping her company. In her vulnerable state, Mari lets him help.

As they talk, they reveal small fragments of their histories, breaking through their guardedness. Leo admits he has been frozen since Alexander’s death and confesses the pressure of an expensive second shop Alexander opened shortly before dying.

Mari encourages him to stop retreating and consider celebrating the store’s upcoming 100th anniversary. They agree to start over.

As Mari recovers, she and Leo begin planning the festival together, digging through Judith’s old albums to find the shop’s history. They discover Judith once knew the famous thriller writer Tommy Clifford and decide to visit him in Somerset.

On the train ride, Mari and Leo share personal stories—her mother’s death, his love for art, his sisters. At Tommy’s cottage, Mari’s gentle determination persuades the author to reconsider participating in the event, even though he had distanced himself from Alexander long ago.

Back in London, the working partnership deepens. Mari feels a growing attraction to Leo, while he battles jealousy and self-doubt.

After an almost-kiss on a late train, they confront their tension in his office. Mari clarifies that she does not fancy Graham, and Leo admits how intensely he wants her.

Honest conversation quickly turns into physical intimacy. They decide to continue secretly and exclusively until her contract ends.

Leo rents a small Airbnb where they can be alone, and there they navigate their inexperience, fears, desires, and vulnerabilities with surprising tenderness. Through this time together, Leo becomes steadier and more confident, while Mari battles her rule of never letting herself fall for anyone.

Their bond grows beyond sex. Mari teaches Leo to cook small comforting meals; he opens up about his eating struggles and past hurts.

They laugh, argue, and share details of their families. Mari’s newly discovered biological family invites her to visit, and though the gathering overwhelms her, Leo supports her through the emotional turmoil afterward.

Their connection deepens, though Mari tries to insist that everything is temporary.

As spring approaches, Ross & Co. comes alive again.

Mari’s marketing pushes, social media strategy, and community outreach help the festival begin with excitement. The shop fills with readers, authors, chatter, and energy.

Graham and Catriona rekindle their relationship. Mari glimpses the life she could have in London, yet she reminds herself she belongs in California.

During the festival, Judith calls a family meeting with Leo and Mari. She reveals that Vinay’s firm still wants to buy the building and that she believes Leo should consider selling to free himself from Alexander’s expectations.

Mari is stunned to learn Leo kept the renewed offer from her. Feeling betrayed, she says she poured herself into saving the shop not knowing he might sell it.

In desperation, Leo says he will keep the store only if she stays. Mari cannot give up the life she built in California, and she reminds him their relationship began with an end date.

Leo finally speaks plainly: he wants her deeply, sees her as the season that revived him, and hopes she might choose a life with him. She acknowledges she made honesty difficult but says she still has to return home.

They leave together, their future unresolved, as the shop door closes behind them—marking the end of her London winter and a lingering question of what, if anything, will follow.

Characters

Mari

Mari is the emotional core of Love Walked In, arriving in London as a professional problem-solver and gradually revealing how much of her own life needs healing. At the start, she is defined by competence and control: she believes fiercely in bookstores as community refuges, knows how to fix failing shops, and is unafraid to challenge Ross and Co.’s stagnation. That confidence, however, covers older wounds.

Her mother’s death, her stepfather’s destruction of the garden, and a childhood of not quite belonging have taught her to keep her heart protected, to choose sex and closeness without “big feelings,” and to frame love as a dangerous vulnerability rather than a goal. This tension between a woman who creates community for others and refuses emotional community for herself drives her arc.

Her relationship with Leo exposes how much she longs for connection despite her self-protective rules. She is nurturing and practical when she is not overwhelmed: she helps him imagine new futures, feeds him without shaming his eating, and offers patient, explicit sexual communication that reframes intimacy as something that can be negotiated rather than endured.

Yet the same woman who can calmly teach him “Show and Tell” in bed panics when faced with a noisy, loving extended family that suddenly claims her. The scene with Jamie’s family shows her trauma most clearly: she cannot process so many people wanting her at once, reads love as pressure, and feels she has not “earned” anyone’s affection.

Her instinct is flight, emotional withdrawal, and insisting on temporariness.

Professionally, Mari is an agent of change and vision. She spots the problems in the shop immediately, pushes for returns, creates the festival, and understands modern tools like social media and “minnows” bookstores.

She is imaginative and strategic, dreaming of that small high-street shop even as she knows it is not hers. Her love for books and readers is consistent and sincere, and that love often offers her more courage than she claims to have in her personal life.

With Leo she slowly edges toward emotional honesty, admitting “Maybe I could love you,” and later forcing herself to be honest about still needing to return to California. Her final conflict with him is not about feeling nothing, but about honoring her own autonomy and unresolved past while being drawn to a life she has built in London.

Mari is thus portrayed as a woman learning that love, belonging, and obligation are not the same thing, and that choosing people and places must come from internal readiness rather than external pressure, even when the love offered is real.

Leo Ross

Leo begins as a classic romantic hero in disguise: prickly, exhausted, defensive, and deeply wounded, hiding gentleness and artistic sensitivity behind sarcasm and control. The failing bookstore is both his burden and his shield.

He clings to Alexander’s legacy as a way to avoid making decisions, terrified of failing the grandfather he loved and equally afraid of confronting what he actually wants. Depression, insomnia, and long-standing guilt leave him paralyzed; his rigidity over the stock, his hostility to returns, and his insistence that staff cannot change anything all come from fear that any alteration will be a betrayal.

Those same anxieties shape his initial cruelty to Mari: mocking romance, belittling her expertise, and telling her to “fuck off” when she challenges his avoidance.

Underneath, however, Leo is compassionate and responsive once someone breaks through his defenses. His care for Mari when she is ill is meticulous and tender: he calls the helpline, buys supplies, sits with her vulnerability, and shares pieces of his own life.

His bond with his sisters, especially Sophie, reveals his capacity for ordinary love and responsibility; he promises to take her to the match, regrets when he fails her, and uses humor and affection with the twins. As a lover, Leo is anxious and ashamed, convinced he is “shit at sex” because of one bad, mutually inexperienced relationship.

Mari’s patience and explicit guidance allow him to reconceptualize sex as something he can learn and even excel at. He becomes intensely attentive to her needs, eager to please, and openly enthusiastic rather than aloof.

This transformation from fearful to eager lover parallels his gradual willingness to imagine futures beyond Ross and Co.

Leo’s central struggle is divided loyalty: to Alexander’s memory, to his family’s financial security, to his own desires, and to Vinay’s very real needs. The offer to sell the building confronts him with the possibility of escape and reinvention, including chasing a life with Mari in California.

Yet, because Mari keeps insisting the relationship is temporary, he cannot trust that leap. His secrecy about the offer is a mix of cowardice and romantic desperation: he does not want to hurt her by admitting he considered selling, but he also does not want anything that might hasten her departure.

When he finally begs her to stay, he speaks with unprecedented clarity, calling her his “spring” and offering to stand with her as she faces her past. Leo moves from passivity and inherited obligation to active choosing: he wants her, he is willing to give up the suffocating life for a different one, and he is finally willing to let Ross and Co.

go if that is what sets them both free. Whatever specific decision he makes about the building, Leo’s character arc is about learning that love and legacy are not the same, and that he deserves a life shaped by his own wants, not only by grief and duty.

Judith

Judith is the quiet moral anchor of the Ross family and the shop, embodying a generous, pragmatic love that can let go when necessary. As Alexander’s widow and Leo’s step-grandmother, she bridges past and present.

She welcomes Mari kindly from the beginning, trusting expertise over pride, and is one of the few characters who both cherishes tradition and recognizes when it has become a trap. Judith understands the emotional significance of Ross and Co.

but refuses to romanticize its financial reality. Her decision to assign Mari to work with Leo is strategic: she sees that Leo cannot rescue the shop alone and that he needs someone strong enough to confront his stagnation.

The discovery of Judith’s youthful connection with Tommy Clifford adds depth to her character. The old photo reveals a history of passion and possible heartbreak, while her reluctance to talk about the rift with Tommy suggests she knows firsthand how ego and wounded pride can destroy relationships.

That experience likely influences her advice later: she advocates selling the building not out of coldness, but because she has learned that clinging to the past can cost the living too dearly. Her encouragement for Leo to free himself from Alexander’s expectations positions her as someone willing to dismantle the shrine to her late husband so that her grandson can have a future.

Judith’s support of Mari is subtle but crucial. By insisting Mari attend the family meeting about the sale, Judith acknowledges Mari’s emotional and professional stake in the shop.

She treats Mari as family before Mari can accept the label for herself. There is firmness in Judith’s love: she does not soften the truth about the shop’s finances or Leo’s limitations, and she is willing to be the one who speaks the uncomfortable reality aloud.

In that sense, Judith functions as a counterpoint to both Mari and Leo: she embodies the mature understanding that love sometimes means stepping back, closing chapters, and trusting the younger generation to write their own stories.

David Ross

David, Leo’s father, represents a generation burned out on the realities of bookselling and eager to abandon ship. From the outset, he is cynical about the business, openly uninterested in saving the shop, and emotionally detached from the sense of legacy that weighs on Leo.

Where Leo sees obligation and memory, David sees a failing business he would happily walk away from. This cynicism complicates Leo’s burden: he is effectively carrying the emotional weight of Alexander’s legacy almost alone, without paternal support.

David’s attitude also provides a contrast to Mari and Judith. His indifference highlights how unusual it is for non-family staff to care more than an heir does, and how much more emotionally invested Judith remains.

His disengagement pushes Leo toward paralysis rather than rebellion; with a father who does not care, Leo has no model for responsible, flexible leadership, only a binary between clinging to the past and abandoning it. Though David does not have many scenes, his presence underscores the novel’s exploration of inheritance: what happens when one generation shrugs off responsibility and the next feels chained to it.

David’s lack of passion for either the store or Leo’s inner life leaves Leo starved of validation, making him more susceptible to guilt and less able to envision alternatives on his own.

Graham

Graham is a crucial stabilizing force in the story, functioning as both comic relief and chosen family. Professionally, he is competent and charming, one of the few staff members actively keeping parts of Ross and Co.

afloat. He befriends Mari quickly, helping her with practical tasks like returns and showing her around the store.

That immediate ease between them creates a false romantic red herring for Leo but actually reveals Graham’s natural warmth, not romantic interest. His familiarity with the shop’s dynamics allows him to serve as a translator between Mari’s American directness and the staff’s quieter, bruised loyalties.

Emotionally, Graham is a bridge between disparate people: he is Vinay’s friend from university, he is part of Jamie’s household with Rosie the Labrador, and he becomes almost an instant sibling figure for Mari as they embrace and fall into teasing. His role in Graham and Catriona’s rekindled relationship further cements his softness and desire for genuine connection.

Rather than compete with Leo, he nudges people toward happiness—encouraging Leo to consider his dreams, supporting Mari’s festival ideas, and finally confessing his feelings to Catriona.

Graham’s presence in Jamie’s home also helps Mari feel immediately less like an intruder. His hug at the door and his affectionate banter signal a family culture that is playful and welcoming rather than hostile or judgmental.

In many ways, Graham models the kind of steady, grounded affection Leo and Mari are both frightened to trust. He is not tormented by legacy or afraid of big feelings; he simply likes people and wants them to be themselves.

Catriona

Catriona is the sharp, direct counterpart to Graham’s warmth, providing the book with a voice that is blunt but ultimately loyal. As the fiction buyer, she is competent and imaginative, having transformed part of the basement into an inviting Gallery space even amid the shop’s larger stagnation.

Her creativity shows that pockets of innovation have existed at Ross and Co. , but they have been limited by lack of leadership.

Initially skeptical of Mari, Catriona represents staff who have watched outside “solutions” fail or never materialize. Her hesitation is less hostility than weary caution.

Her interactions with Leo and Graham suggest someone who sees more than she comments on. She recognizes Leo’s earlier gloom and later “swagger,” teases Mari about the hickey, and is perceptive about emotional undercurrents even when she pretends not to care.

Her eventual praise of Mari’s work on the festival reflects a willingness to revise her opinions when evidence changes. Catriona’s developing relationship with Graham, rekindled by his confession of still having feelings for her, mirrors Mari and Leo’s story in miniature but with less angst.

They are proof that second chances are possible and that open communication can repair old wounds more easily than either expects.

Catriona’s presence in the story underlines the theme that community and partnership make creative projects work. Her Gallery, her romance with Graham, and her ultimate support for Mari’s festival show a woman who is not afraid of passion or change once she is convinced it is sincere and sustainable.

Suzanne

Suzanne, though present mostly in Mari’s backstory, is a ghostly influence in Mari’s professional life and sense of self. As the mentor who trained her in bookselling, Suzanne effectively gave Mari a language and philosophy for creating refuge through bookstores.

Mari’s confident presentation of independent bookshops as community hubs, her ability to diagnose Ross and Co.’s problems, and her willingness to travel across the world for this job all stem from the foundation Suzanne provided.

Emotionally, Suzanne’s role is more complex. She represents a stable adult who saw Mari’s strengths and invested in them at a time when Mari’s family life was fractured.

That investment gave Mari competence and identity but did not fully address her unresolved grief and fear of attachment. Suzanne taught her how to build community for others, but not necessarily how to receive it for herself.

The fact that Mari keeps returning to Suzanne’s philosophy, even as her personal life spins into vulnerability with Leo and her new family, emphasizes how deeply she needs the structure and purpose that mentorship gave her.

Alexander Ross

Alexander, though dead before the novel begins, dominates Ross and Co. and Leo’s psyche.

He was the beloved owner who ran the shop with warmth and energy, and everyone’s memories of him are tinged with affection and nostalgia. The store’s physical state—a frozen relic of his era, complete with outdated stock and rigid layout—mirrors the emotional hold he still has.

For Leo, Alexander is both model and prison: the grandfather who believed in him and trusted him with the business, but also the man whose decisions (like opening an expensive second location) contributed to the shop’s precarious position.

Because Alexander is remembered as almost mythically good, it becomes difficult for Leo to question any of his choices or to admit that the world has changed. The legacy becomes unchallengeable dogma instead of a living tradition.

Judith’s eventual willingness to sell the building marks a quiet rebellion against the way Alexander’s memory has been used to freeze everyone’s lives in place. The conflict encapsulates the novel’s thematic question: how long must the living sacrifice themselves to honor the dead.

Alexander himself is likely more complex than the shrine suggests, but the characters’ idealized recollection of him reveals how grief and hero worship can distort the present.

Vinay

Vinay stands at the intersection of friendship, ambition, and moral compromise. As Leo’s university friend turned real estate developer, he brings the central external conflict into the narrative: the possibility of selling the building.

His initial suggestion that developers might buy the shop is pragmatic, not malicious. To Vinay, the building is an asset; to Leo, it is a legacy and a cage.

Yet Vinay is not a one-dimensional antagonist. His own life is under pressure: he has a pregnant wife, Sonali, and a strong desire to secure a larger home and financial stability for his family.

The commission from the sale would change their lives.

Vinay genuinely cares about Leo. He encourages Leo to consider art school, to think about what he actually wants rather than what Alexander ordained, and even plants the idea that the windfall could allow Leo to follow Mari to California.

His argument is not “sell because I profit,” but “sell because your life does not have to be this. ” That layered motivation makes his role morally ambiguous and emotionally potent.

When Judith later echoes his view that Leo should sell, it becomes clear that Vinay was not simply trying to exploit an old friend, but articulating a truth several people have been afraid to say aloud. Vinay’s presence forces Leo to confront how much of his suffering is self-imposed and how often he has used the shop as an excuse to avoid making personal choices.

Sophie and Gabi

Sophie and Gabi, Leo’s younger twin sisters, offer a glimpse of his tenderness and the wider Ross family context. Sophie appears more fully on the page, with her football practice, her wish to see Arsenal Women play, and her disappointment when their father forgets.

Her relationship with Leo is one of open affection; her presence lifts his mood despite his depression, and his guilt over not organizing the match sooner shows how much he cares about being a good brother. Gabi exists more in the background but completes the sense of a younger generation watching Leo, relying on him emotionally even as David checks out.

Through the twins, the narrative underlines that Leo’s choices about Ross and Co. are not just about himself and his grandfather, but about what kind of adult he will be for his sisters.

They remind the reader that family love can be uncomplicated and joyful, in sharp contrast to the heavy, duty-laden love tied to the shop. They also offer a parallel to Mari’s sense of not belonging: while Leo has sisters who adore him, Mari is only just discovering siblings and cousins for the first time.

Mr. Gissing

Mr. Gissing, the elderly customer who returns to praise a book Mari recommended, is a small but crucial figure.

His enthusiasm is the first concrete, undeniable proof that Mari’s approach to customers works in the specific cultural context Leo insisted would reject it. This moment forces Leo to reconsider his assumptions about British reserve and the shop’s clientele, and to recognize that Mari’s instinct for human connection is not naive but effective.

Symbolically, Mr. Gissing represents the kind of reader Ross and Co. could be serving better: someone who wants guidance, who values personal recommendations, and who responds warmly when a bookseller takes the risk of engaging. His visit during Mari’s illness also serves as a narrative bridge: his unexpected appearance prompts Leo to go upstairs, where he discovers how sick she truly is, triggering the care-taking sequence that changes their relationship.

Tommy Clifford

Tommy Clifford embodies the long shadow of past choices and unresolved conflicts. As a now-famous thriller writer who once frequented Ross and Co.

and clearly had feelings for Judith, he ties literary reputation and personal history together. His refusal to participate in anything honoring Alexander suggests a deep rift, likely rooted in hurt pride, jealousy, or perceived betrayal.

Mari’s use of his early work and the old photograph to nudge him toward softening shows both her skill at reading people and his lingering emotional vulnerability beneath his gruffness.

Tommy’s eventual willingness to consider attending the festival demonstrates that even long-frozen relationships can thaw under the right circumstances. Judith’s presence and Mari’s mediation help him reframe the past.

His arc, though minor, echoes Leo and Mari’s journey: the past is powerful, but not always final. People can choose to re-enter each other’s lives in new ways if they are willing to confront old pain honestly.

Becca (Bex)

Becca, Leo’s ex-wife, personifies a life path Leo has already tried and found hollow. When she appears in the park, newly married to Paul and carrying daffodils, she is calm, self-assured, and clearly past their shared history.

The contrast between their simple registry wedding and the “fussy” wedding she once had with Leo highlights how much she has changed her own expectations of happiness. Her comfortable body language with Paul and the dog suggests she has found a more compatible life elsewhere.

For Leo, seeing Becca is a shock that throws his emotional progress with Mari into sharper relief. Becca functions as a mirror: she is someone he once tried to build a future with, in a version of himself that was anxious, inexperienced, and deeply unsure.

His rigidity and sexual insecurity during that relationship likely contributed to its failure. The meeting with Becca shows how far he has come with Mari, who gives him a completely different experience of intimacy and communication.

Becca is not demonized; she simply belongs to a chapter that is closed, prompting Leo to recognize that his feelings for Mari are not a repetition of old patterns but something genuinely new.

Paul and Rug

Paul, Becca’s new husband, and his dog Rug are gentle, grounding presences in an emotionally fraught encounter. Paul’s story about rescuing Rug, and the dog’s immediate affection for Mari, introduce warmth and kindness into a potentially painful scene.

While Leo and Becca navigate their history, Paul’s easy friendliness and Rug’s uncomplicated love give Mari somewhere to put her own discomfort. By choosing to throw the ball with the dog, Mari both gives Leo space and finds temporary refuge in simple, joyful interaction.

Paul’s role underscores that good relationships can be modest and steady rather than dramatic. His happy domesticity with Becca symbolizes the life Leo might have had if their incompatibility had not undermined them.

Instead of jealousy, the scene invites Leo to see that Becca has found a partner who suits her, freeing him to pursue something truer with Mari.

Jamie

Jamie is the most significant new familial relationship in Mari’s life, embodying both the promise and terror of belonging. As her newly discovered father, he is awkward, overwhelmed, and eager, trying to welcome her into a large, noisy family all at once.

His home is a hub of warmth: a wife, sons, a dog, siblings, and cousins constantly flowing in. Jamie’s instinct to include everyone in meeting Mari is well-intentioned but emotionally clumsy, as he does not anticipate how overwhelming this deluge will be for someone who has never had such a family environment.

Jamie’s later apology is vital. He tells Mari she never has to be close to anyone out of obligation and that they should “choose each other.

” This reframing acknowledges her autonomy and validates her discomfort, transforming the relationship from something imposed to something potentially intentional. Jamie’s attitude contrasts starkly with the compulsory loyalties that have shaped Leo’s life with Ross and Co.

and Mari’s childhood memories of her stepfamily. In offering her permission to step back, he paradoxically makes it easier for her to imagine returning.

Jamie represents a more mature, flexible model of family: one that does not demand immediate closeness but is willing to build it slowly if she chooses.

Annika

Annika, Jamie’s wife, brings a playful, adaptable energy to Mari’s introduction to her new family. Her joking comment about being Jamie’s wife “for now” until they settle how to name everyone shows she understands the emotional complexity of late-arriving relationships and does not insist on rigid titles.

She quickly notices Mari’s resemblance to Jamie’s mother, which gives Mari a tangible link to a history she has never known.

Annika’s warmth and humor make the chaotic family environment less threatening than it might otherwise feel. She provides a model of how to welcome someone without erasing their discomfort: she teases, feeds, and observes without demanding immediate intimacy.

In a house full of loud male relatives, Annika’s presence also offers Mari another strong woman who has navigated the Mackay family’s dynamics and chosen to stay.

Danny and Tim

Danny and Tim, Jamie and Annika’s teenage sons, help humanize Mari’s new family by reacting to her like ordinary boys rather than mythologizing her. Their interest in cake, biscuits, California, and acting dreams provide conversational topics that are light and accessible.

Tim’s dream of becoming an actor opens an immediate point of connection; Mari can share enthusiasm rather than only processing heavy revelations.

The cousins’ excitement and curiosity are genuine but, en masse, contribute to Mari’s sense of overload. They crowd around her, ask questions, and fuss in ways that feel affectionate to them but intrusive to someone unused to being the center of a family’s attention.

Through them, the novel captures how love can feel suffocating when it arrives without boundaries or pacing.

Hazel and Auntie Simi

Hazel, Mari’s grandmother, storms into the narrative like a force of nature. Her loud displeasure that Jamie nearly kept Mari from her, followed by immediate softening when she sees her granddaughter’s resemblance, demonstrates the Mackay family’s intense emotional style: quick to anger, quick to love.

By declaring Mari a Mackay woman and insisting she is strong enough to handle everything, Hazel offers her a powerful identity claim, but also inadvertently adds pressure. Mari is being told who she is before she has decided what this heritage means to her.

Auntie Simi, arriving with Hazel, participates in the chorus of relatives who are excited and possessive at once. Together, they exemplify a matriarchal energy that is protective, opinionated, and overwhelming.

For a reader, they are vivid and likable; for Mari, they are a tidal wave of belonging she has not yet consented to. Their presence makes Jamie’s later statement about choosing each other even more important, because it counters the instinctive Mackay assumption that blood equals instant, permanent connection.

Adam and Keith

Adam and Keith, Jamie’s brothers, and their sons are part of the noisy crowd of male relatives who descend on the house once they know Mari exists. They symbolize the extended family infrastructure Mari did not know she had: uncles and cousins who are boisterous, affectionate, and utterly unprepared for what their sudden presence might do to a traumatized, introverted newcomer.

Though individually they are not deeply characterized, their collective effect is significant.

Their arrival tips the gathering from a manageable group into overwhelming chaos. The noise, questions, and physical proximity push Mari past her capacity, leading to her emotional shutdown and later breakdown on the train.

Through them, the novel explores how even well-meaning, loving families can inadvertently retraumatize someone by ignoring pacing and consent in their eagerness to claim them.

Sonali

Sonali, Vinay’s pregnant wife, is mostly present as a motivating absence. We hear about her through Vinay’s description of their cramped living situation and his desire for a bigger home so she can quit work and they can raise their child more comfortably.

She is not a villain demanding the commission, nor a saint; she is simply a loved partner whose wellbeing drives Vinay’s urgency.

Her offstage presence adds emotional stakes to the sale of Ross and Co. The money is not just numbers on a contract; it is tied to a real woman’s comfort, a baby’s future, and a family’s sense of security.

Sonali’s influence complicates the morality of the decision: to refuse the sale is, in some sense, to deny Vinay and Sonali that leap forward, even while preserving a historic, beloved space.

Rosie

Rosie, the Labrador at Jamie and Annika’s house, and Rug, Paul’s dog, together form a kind of canine chorus of comfort in the story. Rosie greets Mari at the door of Jamie’s house, providing nonverbal reassurance that this is a friendly, safe space.

Rug’s instant love for Mari during the park encounter offers her an emotional anchor while human interactions around her feel tense or confusing.

The dogs’ uncomplicated affection contrasts with the layered, fraught human relationships. They love without history, without demands, which is precisely what Mari often craves in moments of overload.

Their presence makes the emotional landscape feel more livable, giving both Mari and the reader small, tender breaths amid heavier scenes.

Themes

Grief, Loss, and the Slow Work of Healing

From the first glimpse of Ross & Co. , grief sits in the middle of Love Walked In like another silent character: dust on the shelves, outdated stock, employees drifting without direction, and Leo frozen in place.

Alexander’s death is not just a personal loss for Leo; it has hollowed out the bookstore’s identity, turning it from a lively community hub into a mausoleum of his memory. Leo’s insomnia, depression, and exhaustion show how grief can become a kind of paralysis: he is technically functioning, yet emotionally stalled, unable to make even basic decisions like returning unsold books or updating displays.

Alexander’s failed second shop and the debt it left behind deepen this emotional wound, adding shame and a feeling of having inherited not merely a legacy but a catastrophe. Grief in the novel is not limited to Leo.

Mari carries her own earlier losses: her mother’s death, the destruction of the garden that symbolized her childhood security, the destabilizing experience of growing up with a stepfamily that did not nurture her in the same way. Her insistence on not falling in love is another form of mourning, a quiet grief for the safety she once had and the hurt that followed.

When Leo cares for Mari during her illness, their shared confessions start to re-open spaces that grief had sealed off; he finally admits the shop is failing, and she finally admits how much her past shaped her. The festival is a symbolic act of healing: instead of preserving Alexander’s memory through stasis, they honor him by letting the shop live again.

Judith’s ultimate push for Leo to sell is also an act of compassionate realism; she recognizes that true healing sometimes means releasing an inherited burden. The book suggests that grief never fully disappears, but it can be reshaped into something that allows movement, love, and new choices rather than endless repetition of pain.

Love, Intimacy, and the Fear of Vulnerability

Romantic and emotional intimacy in Love Walked In is always shadowed by fear, yet it is precisely that fear which gives the love story weight. Mari comes into the story with a deliberate policy against “big feelings”: she warns Leo not to fall for her, insists she will not fall for him, and frames their connection as sex, exercise, and temporary pleasure.

Beneath that performance lies terror—terror of attachment, of losing someone the way she lost her mother, and of being hurt by people who are theoretically meant to care for her, like her stepfather who razed the family garden. Leo approaches intimacy from the opposite angle but is just as fragile.

His disastrous marriage to Becca has left him convinced he is “shit at sex” and inadequate as a partner. When he panics at the Airbnb, he is not just worried about performance; he is terrified that if Mari confirms his worst fears about himself, it will validate years of self-doubt and rejection.

What makes their connection compelling is how the book shows intimacy as a skill built through honesty, not as an automatic outcome of desire. Mari’s “Show and Tell” game transforms sex from a test Leo can fail into a shared experiment in pleasure and communication.

As they talk about triggers, preferences, past hurts, and bodily comfort, their emotional nakedness becomes as meaningful as their physical nudity. Yet the fear never entirely disappears.

Even as Leo starts to imagine a life with Mari in California, he pulls back from saying he loves her, while she repeats that their time has an expiration date. Her midnight murmur, “Maybe I could love you,” signals how vulnerability creeps in despite her intentions.

By the end, when Leo calls her his “spring” and begs her to stay, the book acknowledges that love cannot eliminate fear or guarantee a future. It can, however, make fear worth facing and push people to confront truths they have avoided.

Home, Belonging, and Found Family

Questions of where and with whom one truly belongs ripple through almost every relationship in Love Walked In. Mari begins the story as a woman without a stable sense of home: she has California, Suzanne’s mentorship, and a bookstore she loves, but emotionally she still feels like the girl whose garden was destroyed and whose mother’s memory was overwritten by a new family structure.

Her trip to London is supposed to be a temporary work project, yet it becomes a search—conscious and unconscious—for a place where she can finally exhale. Ross & Co.

initially seems like an inhospitable space, but as she builds connections with Graham, Catriona, Judith, and eventually Leo, the shop starts to feel like a refuge. The attic room above the store becomes a strange hybrid space: physically cold and uncomfortable, yet emotionally increasingly warm as Leo brings medicine, coffee, and attention.

The discovery of her father Jamie and his large, boisterous family intensifies this theme. That family gathering is both everything she has theoretically lacked—grandmother, aunts, uncles, cousins—and an experience of sensory and emotional overload.

She is surrounded by people who insist she belongs without having earned it, and that unearned belonging scares her as much as it comforts her. Leo’s recognition of her overwhelm and his ability to remove her from the crush of attention demonstrates another kind of belonging: the intimate belonging in which someone sees your limits and protects them.

Ross & Co. itself is a contested “home.

” For Leo, it is both inheritance and prison, a place tied to his grandfather’s love but also to suffocation and expectations. For Judith, it is memory and duty.

For the staff and customers, it is a community space. Mari’s “minnows” idea of small neighborhood bookshops suggests another model of home: not one grand fortress but many little pockets where people can feel known.

The ending, with Mari still choosing to go home to California while recognizing she will return to Jamie and perhaps to London, suggests that belonging does not have to be singular. A person can hold multiple homes and families across continents, choosing them rather than being trapped by them.

Work, Vocation, and the Meaning of Bookstores

The contrast between David’s cynical view of Ross & Co. as a failing business and Mari’s belief in bookstores as refuges sets up a rich exploration of work as vocation rather than just employment in Love Walked In.

Mari does not see bookselling as a quaint hobby; she sees it as labor that creates community, matches people with stories that shape their lives, and offers sanctuary from a world dominated by algorithms and online retail. Her first walk through Ross & Co.

, observing apathetic staff and dusty shelves, is not about aesthetics alone; it is a diagnosis of a vocation that has lost its purpose. Leo, paralyzed by grief and fear, insists that British customers do not want friendliness or recommendations—a justification for doing less, but also a sign that he no longer trusts his own instincts as a bookseller.

Mari’s small act of helping Mr. Gissing and the way that recommendation transforms his experience undermines Leo’s belief and confirms her philosophy: personal engagement still matters, even in a digital age.

The festival becomes the clearest embodiment of the idea that bookstores are more than retail spaces. By inviting authors, celebrating the shop’s history, and rallying the community, Mari and Leo turn Ross & Co.

back into a living organism. The use of Bookstagram and BookTok shows how vocation can adapt rather than reject new tools: social media is not presented as an enemy but as a way to amplify the personal magic of recommendations to a wider audience.

Yet the book also acknowledges that passion is not always enough to counter financial reality. The developers’ offer, Judith’s practical recognition that Leo did not choose this life, and the constant pressure of money complicate any romantic ideal of vocation.

Selling the building could mean ending Ross & Co. but also freeing Leo to pursue his art or a different future.

Work here is portrayed as meaningful when it is chosen and aligned with one’s gifts, not simply inherited. Mari’s vision of a tiny neighborhood shop, done “for love,” flags that vocation is less about prestige and more about the daily joy of matching people to stories, even in a small corner of a city.

Change, Tradition, and the Courage to Let Go

From the first clash over returns to the final debate about selling the building, Love Walked In constantly pulls its characters between preservation and change. Alexander represents a golden age of Ross & Co.

, but also a set of decisions—like opening a second location—that have left the current generation burdened. Leo’s refusal to touch the stock, reorganize the shelves, or modernize the store is framed as loyalty, yet the story gradually reveals that this loyalty has hardened into fear: if he changes anything, he worries he will betray his grandfather’s memory or admit that the old model is no longer viable.

Mari’s arrival acts as an agent of disruption. Her willingness to pull unsold books, revamp inventory, and build an online presence threatens Leo precisely because it collapses the illusion that nothing can be done.

Their argument over the returns is not only about cardboard boxes; it is about whether the past must be preserved untouched or whether honoring it requires evolution. Judith’s stance is crucial here.

She loves Alexander and the shop, yet she is the one who finally argues that Leo should sell. Her perspective reframes letting go as an act of love rather than betrayal: she does not want him chained to a life chosen for him by someone else, no matter how beloved.

The encounter with the antique shop—beautiful space, doomed business—also acts as a warning. Without adaptation, even places with “good bones” vanish and are replaced by something sleeker, emptier, more profitable.

Leo’s imaginative leap toward California, spurred by Vinay’s suggestion that selling could fund a new life, is another moment where the book asks whether clinging to a single narrative of who you are is worth the cost. In the end, change is shown as frightening but necessary; tradition can be honored through remembrance, festivals, and stories, but it cannot demand that the living stay frozen so the dead can be comfortable.

Communication, Consent, and Sexual Self-Discovery

One of the most striking aspects of Love Walked In is the way it treats sex as a site of learning, communication, and ethical care rather than mere titillation. Leo’s confession that he is “shit at sex” and his panic at the Airbnb stem from more than awkwardness.

His previous partner’s inexperience, lack of guidance, and implied criticism have left him with a warped sense of his own desirability and ability to give pleasure. Instead of laughing, shaming, or brushing past his fear, Mari slows everything down.

Her “Show and Tell” approach reframes sex as a conversation where both people get to articulate what they like. She explains her preferences, demonstrates touches, invites him to experiment with his own body, and narrates her reactions so he can understand what works.

This explicit communication is mirrored later when they discuss practicalities: where to have sex, who will pay for the Airbnb, condom use despite her IUD, and testing. The insistence on exclusivity “until she leaves” is another negotiated boundary rather than an unspoken assumption.

Through these scenes, the book foregrounds consent as enthusiastic, ongoing, and multidimensional. It’s not only about yes or no to intercourse; it is about comfort with being watched, being eaten, being touched in particular places and ways, and being emotionally exposed.

Their habit of joking about “blue balls” or teasing each other about desire becomes part of an open, shame-free sexual language that allows Leo to feel wanted rather than judged. At the same time, Mari’s sexual confidence is not portrayed as without vulnerabilities.

She admits she does not actually have penetrative sex that often, and the revelation of her garden tattoos and the story behind them opens another layer of intimacy. Sex becomes a route to self-discovery for both of them: Leo learns he is capable, generous, and responsive; Mari realizes that sharing stories, not just bodies, is what makes her feel truly seen.

Autonomy, Boundaries, and the Right to Choose One’s Life

Threaded through the relationships and plot decisions of Love Walked In is a persistent insistence on personal autonomy, even when choices are painful. Mari’s repeated statement that she will not fall in love is a defense mechanism, but it is also an attempt to assert control over her emotional life after a childhood where major decisions—her mother’s remarriage, the destruction of the garden—were imposed on her.

Her career as a bookseller, her decision to come to London for a finite project, and her insistence on paying her share of the Airbnb or refusing Leo’s financial dominance all reflect a fierce desire not to be beholden to anyone. Leo, in contrast, has spent years living out a script written by others: Alexander’s expectations that he will inherit the shop, David’s disinterest in taking responsibility, even Sophie and Gabi’s reliance on him as the more stable adult compared to their father.

His depression is partly the result of having almost no sense of agency. Vinay’s offer, Judith’s plea to sell, and Mari’s festival all push him toward making an active decision about his own future.

The book does not simplify autonomy into selfishness. Jamie’s reassurance that Mari never has to be close to people out of obligation and that families should “choose each other” undercuts the idea that blood automatically demands sacrifice.

Mari’s overwhelmed breakdown after meeting the extended Mackay clan and her subsequent choice to consider returning on her own terms show that real connection is meaningful only when it is freely embraced. Similarly, Leo’s declaration that he wants her to stay, that she is his “spring,” is heartfelt, but the novel respects her need to go home and sort out her life instead of merging with his by default.

Autonomy here means accepting that love does not override every other claim on a person’s identity; careers, geography, family history, and mental health all matter. The bittersweetness of their parting is precisely what makes their earlier declarations of exclusivity and devotion feel earned rather than forced.