The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore Summary, Characters and Themes

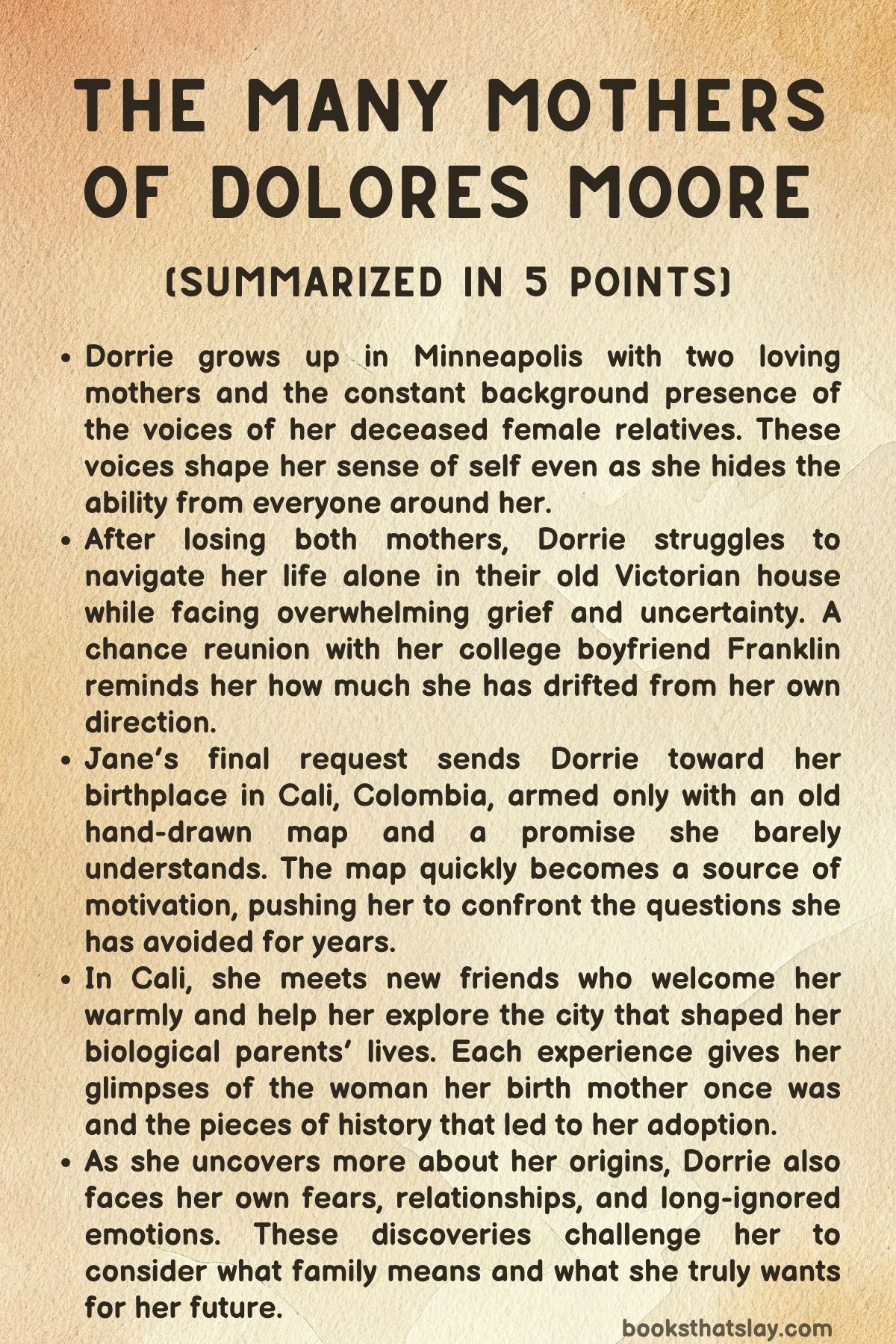

The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore, by Anika Fajardo, is a story about identity, loss, and the long path toward belonging. It follows Dolores “Dorrie” Moore, a woman raised in Minneapolis by her two mothers, who has lived her life quietly avoiding uncertainty.

After the sudden deaths of both mothers, she is left alone with a strange inherited gift: she hears the steady, sometimes intrusive voices of her deceased female relatives. When grief and circumstance push her toward Colombia, the country of her birth, she reluctantly begins a search for her origins. The novel moves between past and present, uncovering the lives that shaped her and the new life waiting for her.

Summary

Dorrie Moore grows up in Minneapolis with her two mothers, Jane and Elizabeth, in a Victorian house full of warmth and routines that anchor her. After her grandmother dies, she begins hearing a chorus of dead female relatives.

They never speak directly to her, but they comment, bicker, advise, and critique as though they are forever standing just behind her shoulder. She never reveals this to anyone, accepting it as something that simply exists within her life.

As the years pass and more relatives die, the chorus becomes larger and louder.

By the time Dorrie is thirty-five, both her mothers are gone—Elizabeth from a sudden heart attack and Jane after a long decline. Left as the last living Moore, she moves through the days around Jane’s funeral with emotional detachment, surrounded by people who express sympathy while she struggles to recognize her own place in the world.

A campus map without a “YOU ARE HERE” dot captures her internal state: she feels unmarked on the map of her own life.

During a video call, her best friend Becks reminds her of Jane’s final request. Days before dying, Jane had asked Dorrie to go to Colombia, where she was born, and to visit Cali, the city where her biological mother Margaret and her father once lived.

Jane spoke with regret about the fears that kept them from taking Dorrie there earlier and urged her not to live a life shaped by hesitation. Dorrie promised she would go, though the idea terrifies her.

After the funeral, Dorrie has a sudden panic attack and collapses on her porch, only to be helped by a paramedic who turns out to be Franklin Liu—her kind, awkward college boyfriend whom she has not seen in years. He explains she is experiencing acute stress, not a medical emergency, and the encounter leaves her shaken but steadier.

That evening, she hears Jane’s voice join the chorus for the first time. The shock of it breaks through her numbness.

She realizes that if she is to honor her promise and find the truth of her beginnings, she must face the journey alone.

The narrative shifts to the past: Margaret “Maggie” Moore travels the world as a restless young woman. She meets Juan Carlos, a charismatic Colombian, in Rome by accident when he trips over her sandals.

Their connection is immediate and intense. They eventually move to Cali in 1989, living in a tiny courtyard apartment owned by Doña Rojas and her daughter Cristina.

Maggie loves the city’s markets, river walks, food, and rhythms, settling into a life that finally feels steady. She practices Spanish, uses a worn map Juan Carlos marked with his favorite places, and imagines a shared future.

When pregnant, she photographs daily life, unaware that one image Cristina takes of her will become the only picture of her during pregnancy.

In the present, Dorrie uncovers Maggie’s old passport and the hand-drawn Cali map hidden in Jane’s desk. The map feels like a sign pointing her toward what she has avoided for decades.

Around this time, Franklin reenters her life again, helping her clean up after she accidentally pulls a desk onto herself. Wine, shared stories, and grief pull them close, and they sleep together.

It is a brief reunion but leaves Dorrie with more clarity: she is going to Colombia.

In Cali, she stays at Hotel América, a place tied directly to Maggie’s past. She befriends Trina, Seb, their child Andrés, María Sofía, and teen Hannah, who fold her into their lively circle.

Dorrie visits churches, markets, and the river, trying to match the map’s markings to the city around her. She discovers that her name, Dolores, likely comes from La Ermita’s dedication to Nuestra Señora de los Dolores—Our Lady of Sorrows—and this realization stirs both recognition and discomfort.

She buys a bold red bikini after an embarrassing misunderstanding in a boutique, continues exploring, and grows close to her new friends. Oscar, a friend of Seb and Trina, expresses interest in her, but despite a few kisses and attempts at connection, she feels uncertain.

After a night of rum, dancing, and wandering along the river, she becomes violently ill and spends days recovering. Franklin, still in touch from Minnesota, talks her through symptoms and reassures her over video calls.

While sick in bed, she finally confides something she has never told anyone: she hears the chorus of dead relatives. Franklin listens without disbelief, easing a loneliness she has carried for years.

The story returns to 1989. Juan Carlos dies in a cartel bombing while traveling with his family.

Maggie, left alone and near childbirth, falls into silent devastation until she calls Jane and begs her to come. When Jane arrives, Maggie insists that nothing could have prevented the tragedy and that she still loves Colombia.

Soon afterward, Maggie dies suddenly, leaving her baby behind. Jane brings the newborn home and names her Dolores.

Back in the present, Dorrie returns home from Colombia, but her life unravels when a car crash, kitchen flooding, and emotional exhaustion leave her overwhelmed. While being treated after the accident, she learns she is pregnant.

She avoids telling Franklin and tries to decide her future alone, until a confrontation with her ex Jason forces her to assert her independence.

As she begins rebuilding her home and her confidence, she finds old photos of Maggie and Juan Carlos, seeing their faces clearly for the first time. At Bao’s funeral, which she attends to support Franklin, she realizes she is no longer the last Moore: the baby she carries ends her sense of being an “endling.” She reconciles with Becks and decides to keep the baby.

Later, Franklin approaches her, newly single after ending his engagement. When Dorrie tells him she is pregnant—and that the baby is his—he responds with steady acceptance.

The final scenes show Dorrie months later, living with Franklin in her mothers’ old bedroom, caring for their newborn daughter, Margarita. Her house is partly restored, her family expanded, and the chorus of voices has finally grown quiet.

She has found her own place on the map, built from both the past she uncovered and the future she chose.

Characters

Dorrie (Dolores Moore / Dolores Pelletier-Moore)

Dorrie is the emotional and narrative center of The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore, shaped deeply by displacement, loss, and the search for identity. Raised in Minneapolis by her two mothers, Jane and Elizabeth, she grows up with love but also with an internal fragmentation symbolized by the “chorus” of deceased female relatives whose voices accompany her from childhood.

These voices become metaphors for generational memory, inherited identity, and the pressure of expectations she never chose. As an adult, Dorrie is defined by a profound sense of rootlessness—she is an adoptee who has never visited her birth country, a cartographer who ironically cannot locate herself on her own life map, and a woman who has lost all parental figures by the age of thirty-five.

Grief leaves her numb and suspended, and her panic attack after Jane’s funeral reveals a lifelong pattern of repressing emotion in favor of competence and control. Her journey to Colombia becomes both an honoring of a final promise and an existential necessity, pushing her to confront the origins she has avoided.

There, she oscillates between vulnerability and quiet resilience as she navigates language barriers, illness, connection, and desire. Her pregnancy ultimately anchors her in a newfound continuity—she is no longer an “endling,” and the chorus of voices fades as she forms her own family.

Through Dorrie, the novel explores how identity is constructed not only from biology or culture but from the relationships we choose, the griefs we endure, and the stories we reclaim.

Margaret “Maggie” Moore

Maggie’s story brings emotional depth and historical weight to The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore, illuminating the life that preceded Dorrie’s adoption. Maggie begins as a restless traveler, hungry for adventure and resistant to settling down, until her relationship with Juan Carlos transforms her wandering impulses into a longing for rootedness.

Through her life in Cali, she discovers belonging in small domestic rituals, warm community interactions, and the slow weaving of a shared life built in a courtyard apartment. Her arc is characterized by tenderness, idealism, and a willingness to adapt, as she embraces Colombia instead of exoticizing it.

Maggie’s pregnancy both steadies and complicates her identity; it tethers her emotionally to the future she shares with Juan Carlos. When he and his family die in the plane bombing, Maggie’s world collapses into profound, isolating grief.

Her silent unraveling reflects the fragility of hope and the unbearable weight of sudden widowhood in a foreign land. Summoning Jane is both a plea for rescue and an act of surrender.

Yet even in her final decline, she expresses a desperate wish that her child be surrounded by love and never be alone, creating the emotional mandate that shapes Dorrie’s entire life. Maggie remains a haunting presence—both lost and rediscovered through memories, maps, photographs, and the uncanny chorus of female voices that follow her daughter.

Jane Moore

Jane is the stabilizing force of The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore, a mother defined by devotion, practicality, and a quiet capacity for endurance. As Maggie’s older sister, she steps into caretaking roles long before adopting Dorrie, and her love is expressed through action rather than sentimentality.

Jane’s partnership with Elizabeth creates a home built on warmth, structure, and intellect. She is pragmatic yet deeply emotional beneath the surface, a woman who manages crises while burying her own vulnerabilities.

Her dying request that Dorrie go to Colombia reveals profound insight into Dorrie’s inner voids: Jane understands that her daughter has long followed other people’s needs, careers, and expectations, never carving out a path for herself. Through this request, Jane offers both permission and a push toward self-definition.

Even after her death, when she joins the chorus of voices, her presence becomes a catalyst for Dorrie’s emotional breakthroughs rather than a source of haunting. Jane embodies the novel’s theme that motherhood is an act of continual guiding—one that shapes identity even after death.

Elizabeth Moore

Elizabeth, though gone at the beginning of the novel, remains a formative emotional presence in The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore through Dorrie’s memories and the chorus of voices. She is softer, more artistic, and more openly affectionate than Jane, balancing the household with warmth and humor.

Elizabeth’s sudden death leaves a raw wound that shapes Dorrie’s understanding of loss—the abruptness of it destabilizes her sense of safety and contributes to her emotional dissociation. In life, Elizabeth encouraged creativity, introspection, and imagination, making her a gentle counterbalance to Jane’s practicality.

Her love was one of daily rituals and emotional openness, and her absence amplifies Dorrie’s loneliness. As part of the chorus, Elizabeth represents comfort and maternal continuity, yet her voice also underscores how profoundly Dorrie has been shaped by the love of the mothers who raised her rather than the biological parents she never knew.

Juan Carlos

Juan Carlos brings romance, cultural depth, and tragedy to The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore, representing both the beauty and fragility of Maggie’s life in Colombia. His love for Maggie is spontaneous and wholehearted, built on humor, sensuality, and openness.

Through him, Maggie experiences Colombia not as a caricature of violence but as a place of rich culture, warmth, and layered history. Juan Carlos embodies the intersection of personal and national identity; he navigates the tension between honoring his conservative family and living authentically with Maggie.

His marked city map becomes a symbol of orientation, belonging, and the geography of love. His death—along with his family—in the bombing is a devastating rupture that reverberates through the entire novel.

Juan Carlos remains both a presence and an absence: the father Dorrie never knew, the love Maggie could not outlive, and the link between two countries and two generations.

Franklin Liu

Franklin is both a link to Dorrie’s past and a surprising compass in her present within The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore. Introduced as her shy college boyfriend, he reappears as an EMT during her panic attack, embodying calm, steadiness, and a kind of emotional competence that Dorrie desperately needs but struggles to accept.

His life has not been linear—failures in med school, work abroad, and his own complex relationships have humbled him, giving him empathy and emotional maturity. As he helps Dorrie with home repairs, yard work, and small daily tasks, he becomes a grounding presence who respects her independence while offering support without demand.

Their intimacy, both past and present, is gentle rather than dramatic, built on shared vulnerabilities and mutual witnessing. When Dorrie confesses the truth about the chorus of voices, Franklin responds without judgment, becoming the first living person allowed into that hidden part of her identity.

His reaction to her pregnancy and his breakup with Sasha mark his commitment to authenticity rather than obligation. Ultimately, Franklin represents a love that is patient, imperfect, and real—a contrast to Dorrie’s lifelong fear of needing others.

Becks

Becks is Dorrie’s oldest and most intuitive friend, a counterpart in vulnerability and emotional history in The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore. Their friendship is rooted in childhood acceptance and emotional refuge.

Becks’ pregnancy journey—marked by miscarriages and grief—parallels and intersects with Dorrie’s evolving relationship with motherhood. Her reactions to Dorrie’s crises are layered: protective, jealous, wounded, and fiercely loyal.

The tension that arises between them is born of deep love and shared history rather than conflict, making their reconciliation one of the emotional turning points of the novel. Becks represents a chosen-family bond that withstands distance, misunderstandings, and transformations.

Trina (and Seb, Andrés, and María Sofía as part of her circle)

Trina is one of the unexpected gifts of Dorrie’s journey in The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore, offering friendship, cultural immersion, and emotional safety. Warm, glamorous, and perceptive, Trina introduces Dorrie to the rhythms of Cali—its social life, sensuality, humor, and hospitality.

Her household, with Seb’s steady presence and Andrés’ childlike trust, gives Dorrie a view of family in motion rather than memory. Trina’s own experiences with loss, miscarriage, and longing for motherhood create an intimate connection with Dorrie, especially during their late-night conversations.

María Sofía and Oscar add texture to this social world; their flirtations, encouragement, and gentle chaos push Dorrie out of isolation and into participation. This group represents the temporary family who guides her until she can stand on her own.

Oscar

Oscar serves as a foil to Franklin and as a catalyst for self-discovery in The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore. He is charming, open, flirtatious, and good-hearted, offering Dorrie affirmation and desire at a time when she feels dislocated.

Their connection is immediate but ultimately superficial—not because Oscar lacks sincerity, but because their encounters reveal Dorrie’s emotional confusion rather than resolve it. His presence highlights her need for clarity, agency, and genuine attachment rather than escapist intimacy.

Oscar’s importance lies not in romantic potential but in helping Dorrie understand what she truly wants.

Doña Rojas and Cristina

Doña Rojas and her daughter Cristina add generational depth to Maggie’s story in The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore, representing the everyday kindness, cultural richness, and interwoven community life of Cali. Doña Rojas provides maternal presence and sanctuary to the young American woman living above her, while Cristina bridges the gap between languages and cultures with shy curiosity and affection.

Cristina’s photograph of Maggie becomes a symbolic inheritance for Dorrie, an artifact of her origins. In the darker chapters of Maggie’s grief, these two women attempt to support and sustain her, showing how motherhood and caretaking transcend bloodlines.

Jason

Jason functions as a sharp contrast to the novel’s themes of chosen family and respectful love. As Dorrie’s ex, he embodies entitlement, emotional immaturity, and coercive assumptions about parenthood and relationships.

His intrusion into Dorrie’s newly complicated life—culminating in his explosive accusations and bigoted remarks about her mothers—marks an important turning point. Rejecting him becomes an act of self-definition and independence.

His presence highlights Dorrie’s growth, her refusal to let others define her choices, and her commitment to protecting the life she is creating.

Themes

Identity and Belonging

Dorrie’s life is shaped by an ongoing tension between who she is expected to be, who she appears to be, and who she feels herself becoming. Her adoption, her upbringing by two mothers in Minneapolis, her Colombian origins, and the chorus of dead women who accompany her create overlapping identities that never settle into a single, solid shape.

Her grief only intensifies this instability. When both Jane and Elizabeth die, she feels not simply bereaved but unmoored, as if the last anchors that once held her to a defined version of herself have vanished.

Her fixation on the campus map without a “YOU ARE HERE” marker reveals her deeper crisis: she has no internal reference point. Traveling to Colombia becomes a physical attempt to locate the metaphorical point she cannot find at home.

Once in Cali, she senses the weight of a culture that is hers by birth but not by experience. Every place she visits and every person she meets pulls her toward a version of herself she has never known.

She reacts with unease, curiosity, and a yearning she struggles to articulate. The discovery of her biological mother’s photograph and the map with a marked “Home” creates a parallel identity—one that could have been hers had history not intervened.

Rather than neatly reconciling these identities, the novel shows her learning to inhabit the spaces between them. The final quieting of the chorus suggests not that she has found one definitive identity, but that she has formed one she can finally inhabit without fear.

Motherhood in Its Many Forms

The novel positions motherhood not as a fixed role but as a continuum shaped by love, loss, distance, lineage, and choice. Jane and Elizabeth create a home grounded in intentional love—two women choosing to mother a child born far from them, knowing that their family structure defies convention.

Their parenting is depicted not as an imitation of traditional motherhood but as its own complete form, defined by tenderness, protection, and investment in Dorrie’s inner world. Meanwhile, Maggie’s story shows biological motherhood colored by both joy and tragedy.

Her pregnancy is steeped in love for Juan Carlos and for the city that becomes her chosen home. But her dreams collapse under the violence that kills him and strands her in grief.

Her call to Jane becomes the moment when motherhood crosses from bloodline to chosen kinship. Later, Dorrie’s pregnancy begins in confusion, panic, and shame, echoing Maggie’s vulnerability but under vastly different circumstances.

As she wrestles with her decision, motherhood becomes not a destiny imposed upon her but something she slowly chooses. The moments when she observes Trina with Andrés, or when she sees Franklin pushing his grandfather in a wheelchair, reveal caregiving as an instinct that moves through her even before she admits it aloud.

By the time her daughter Margarita is born, motherhood is portrayed as something she participates in alongside Franklin and alongside the remembered women whose voices shaped her. The novel suggests that motherhood is a continuum of presence—sometimes loud, sometimes soft, sometimes inherited, sometimes created—and that Dorrie’s life has been formed by many mothers even before she becomes one herself.

Grief, Memory, and the Weight of the Past

Loss defines nearly every turning point in the narrative, and grief is rendered as a state that distorts time, perception, and even the boundaries of the living and the dead. When Elizabeth dies and then Jane follows, Dorrie experiences grief not as sharp emotion but as numbness, exhaustion, and disorientation.

The chorus of voices—both comforting and oppressive—becomes an audible manifestation of memory insisting on attention when she would rather withdraw. Her panic attack after the funeral and her collapse on the porch show grief’s capacity to unsettle the body as much as the mind.

In Colombia, grief expresses itself differently: through the ache of what she never experienced rather than what she has lost. Maggie’s grief, decades earlier, is quieter but devastating.

Her partner’s death in the bombing collapses her world and transforms her from an adventurous traveler into a woman suspended in sorrow, unable to see a future except through the child she carries. The parallel between Maggie’s isolation and Dorrie’s aloneness after her parents’ deaths blurs past and present, binding them across time.

Memory becomes the bridge that keeps the dead alive: through photos, maps, recipes, and even the old Victorian house with its creaking pipes and hidden albums. The quieting of the chorus at the end suggests that grief does not disappear but settles, allowing Dorrie to move forward rather than remain trapped in what she has lost.

Love, Intimacy, and Human Connection

Relationships in The Many Mothers of Dolores Moore are depicted as fragile, surprising, and shaped by timing. Dorrie’s renewed connection with Franklin begins with an unexpected collision between past and present—him appearing as a paramedic during her panic attack.

Their relationship unfolds not as a rekindled romance from youth but as something shaped by adulthood’s scars: his failed attempts at med school, her stalled career, their mutual uncertainty. Their intimacy, first sparked by nostalgia and wine, becomes more grounded when they share vulnerabilities—his worries about his grandfather, her revelation about the chorus of voices.

The relationship grows not through dramatic declarations but through small acts: repairing a kitchen, caring for cats, watching over one another. The novel also emphasizes friendships, particularly Dorrie’s lifelong bond with Becks.

Their temporary rupture after Dorrie’s insensitive timing around her pregnancy news shows how friendship can bend under stress without breaking. The group she meets in Cali—Trina, Seb, Andrés, María Sofía, Oscar—embodies a social warmth she has rarely allowed herself to receive.

Their hospitality helps her feel part of a community, even briefly. Love in the novel is shown not as a single defining relationship but as a network of connections that shape identity—family, lovers, friends, neighbors, even the dead.

By the end, love becomes the foundation upon which Dorrie builds her new beginning: not a return to innocence, but a recognition of intimacy as something she can choose and sustain.

Home, Place, and the Search for Orientation

Dorrie’s sense of place is unsettled from the outset. The Victorian house is filled with love, memories, and the presence of her mothers, yet once they are gone it becomes cavernous, fragile, and almost hostile.

Bursting pipes, broken lights, and chaotic accidents mirror her internal disarray. Colombia, meanwhile, exists at first only as a mythic birthplace and a blank on the map of her life.

When she arrives, the sensory details—heat, color, food, music—pull her into an experience that is both foreign and eerily familiar. Landmarks marked on Maggie’s map give her a structure to follow, but as she explores the city she realizes that place is not simply geography.

It is history, family, and the stories people leave behind. Maggie’s apartment, Doña Rojas’s courtyard, and the riverwalk where she kisses Oscar all blur into a geography of emotional discovery rather than direction.

Home ultimately emerges not as a fixed location but as something she constructs through relationships and decisions: the restored kitchen, the shared bedroom with Franklin, the baby sleeping beside them. The novel suggests that home is not found by following someone else’s map but by creating new paths that acknowledge where one has been and where one hopes to go.

Fate, Choice, and the Maps We Follow

Maps—literal and metaphorical—appear throughout the novel as symbols of direction, destiny, and the tension between wandering and decision. Dorrie is a cartographer by training, yet she repeatedly struggles to orient herself emotionally.

Her mothers often told her she followed other people’s maps, and Jane’s final request becomes a call to create her own. Maggie’s hand-drawn map embodies love, memory, and an unfinished life; its folds and stains preserve a moment in time that Dorrie steps into decades later.

But the map does not give answers. It merely leads her to questions she must confront.

Her pregnancy becomes another moment when fate and choice collide. Though she feels overwhelmed and buffeted by forces beyond her control—grief, illness, unexpected reunions—she gradually learns that decisions define her far more than circumstances.

The novel repeatedly asks whether life is shaped by coincidence, destiny, or the willingness to act: Franklin appearing during her panic attack, the suitcase discovered days late, the hidden album falling into her hands. By the end, she understands that life does not offer a single correct route.

It offers possibilities. Her choice to raise her child, to let Franklin in, and to build a life anchored in the present becomes the map she finally authors herself.