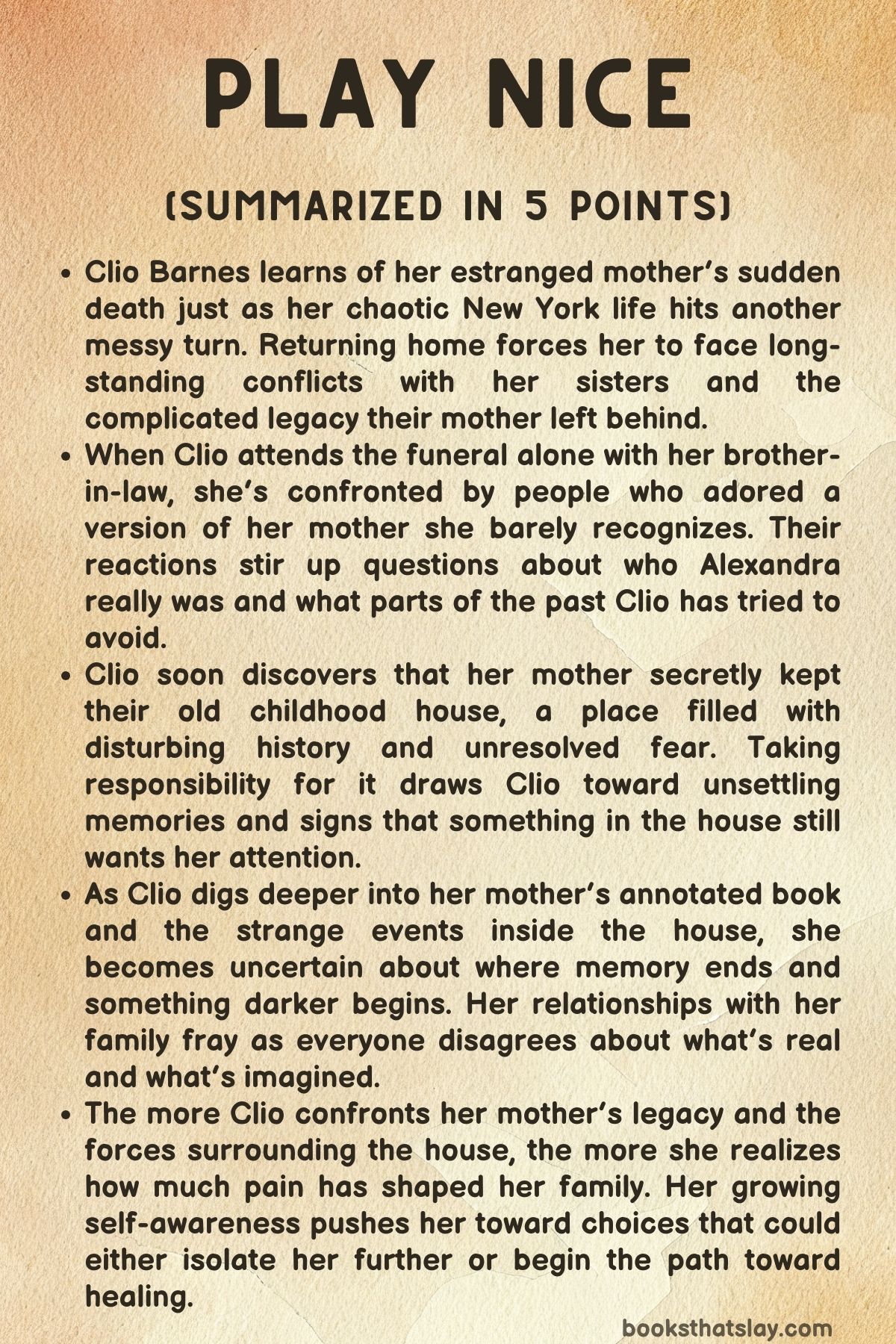

Play Nice Summary, Characters and Themes

Play Nice by Rachel Harrison is a darkly funny and unsettling novel that blends supernatural dread with sharp observations about family loyalty, generational trauma, and the stories we inherit without choosing them. It follows Clio Barnes, a young New York stylist whose messy confidence masks a lifetime of unresolved fears tied to her mercurial mother.

When Alexandra dies suddenly, Clio is forced back into the gravitational pull of her sisters, her childhood home, and a past shaped by a mother who believed their house was alive and watching. What begins as a reluctant family reunion becomes a confrontation with memory, identity, and a presence that refuses to be ignored.

Summary

Clio Barnes learns of her estranged mother Alexandra’s death just after leaving a party in New York. Hungover and shaken the next morning, she travels to her childhood home in New Jersey, where she joins her sisters, Leda and Daphne.

The three share a strained history shaped by Alexandra’s erratic behavior, her supernatural beliefs, and her memoir, Demon of Edgewood Drive—a book the family silently agreed never to read. Their father, long divorced from Alexandra, keeps a cautious emotional distance from the subject of their former life.

When their aunt announces a funeral, the sisters refuse to attend, certain it will be filled with Alexandra’s odd friends and self-proclaimed mystics. Clio decides to go anyway and convinces Tommy, Leda’s husband, to accompany her.

At the elaborate Victorian home hosting the funeral gathering, Clio meets Alexandra’s partner Roy and an eccentric cast of spiritual devotees. There, she learns that her mother never sold the infamous house on Edgewood Drive—the supposed site of the demon Alexandra wrote about—and that she actually died inside it.

Even more startling, ownership of the property now belongs to Clio and her sisters.

Tommy reveals on the drive home that Leda only recently learned the house still existed, and tension rises when Clio suggests she should handle the property herself. Though Leda protests, Daphne sides with Clio’s desire to take it on.

Determined, Clio steals away early the next morning to see the house. Edgewood is exactly as she remembers: tired, still, and unsettling.

She soon notices strange things—a ceiling fan turning without power, muddy footprints, her bed rumpled as though someone had slept in it. She finds Alexandra’s memoir in her childhood room, full of notes addressed directly to her.

When a cold hand seems to grab her neck, she escapes in terror.

Clio becomes fixated on the book, reading Alexandra’s descriptions of the house’s strange sounds, shadows, and moments of confusion that blur into fear. Her father dismisses it as obsession, but Clio feels the house watching her.

She returns again, trying to confront her memories and the relics left behind. One night a teen named Cal breaks in on a dare, apologizes, and introduces her to Austin, his uncle and Clio’s former neighbor.

Austin brings her to his house, where his mother gently suggests that Alexandra was troubled rather than guided by anything supernatural. Clio and Austin grow closer, sharing late nights, weed, sex, and confessions neither meant to tell.

But Edgewood only deepens its hold. Clio experiences cold spots, shifting shadows, and messages scribbled on her sketchpad.

Pages appear that she never wrote. Terrified, she flees but can’t stay away.

Her growing fixation strains her relationships, especially when she discovers her father hid half of Alexandra’s annotated memoir in his study. Their confrontation escalates into a firepit blaze where he burns the book in front of the family, accusing her of becoming like Alexandra.

Clio storms off, furious and unsteady.

She returns to Edgewood alone. Roy is supposed to meet her there, but she finds only his phone.

As she stumbles around the house, the lights flicker, doors slam, and a crushing sense of hostility fills every room. She accidentally begins an Instagram Live, broadcasting the chaos.

The attic ladder appears mysteriously in her closet; climbing it, she falls and breaks her nose. Her sisters—having seen the livestream—rush to the house and find her bloody, frightened, and surrounded by evidence of something wrong.

Inside, the house erupts. Walls scrape themselves into faces, furniture stacks against doors, and rooms shift as though the building is breathing.

The sisters fight each other violently, their buried resentments spilling out. Clio realizes the house—something in it—feeds on their conflict.

She manages to stop them, and when the chaos settles, they hear a faint voice above the closet. Roy is discovered alive but mutilated in the attic crawl space.

Clio climbs inside, where she sees relics from their childhood stored like trophies. A presence reveals itself, enormous and alien, pressing memories into her mind—times she greeted it as a child, times she wasn’t afraid.

She feels it trying to claim her as it did Alexandra. In a moment of clarity, she offers her snake charm necklace, speaks honestly about her pain, her mother, and her sisters, and the presence finally releases her.

Emergency crews swarm the scene. Outside, Clio reconciles quietly with Austin, who admits the house always felt wrong.

Weeks later, she and her sisters share a quiet meal, marked by fragile honesty and the promise of staying connected despite everything they’ve faced.

Months pass. Clio’s accidental haunted-house livestream makes her a minor sensation, unexpectedly boosting her career.

At a glamorous launch event in New York, she reunites with her family. They are on better terms, though not without distance and complicated feelings.

Daphne reveals that the Edgewood house is finally being sold. Clio hasn’t returned since the night of the confrontation and has no desire to.

Reflecting on everything, she decides the only way to defeat something that feeds on fear is to stop feeding it. Standing alone on a balcony, she chooses to face the future on her own terms.

Characters

Clio Barnes

Clio Barnes stands at the center of Play Nice, a woman pulled between the version of herself she projects and the fractures beneath the glitter. At twenty-five, she defines herself through aesthetics, nightlife, and curated chaos, yet beneath this glossy self-presentation lies a profound craving for belonging, validation, and truth.

Her estranged relationship with her mother, Alexandra, becomes the gravitational force that pulls her backward into childhood trauma and forward into dangerous self-discovery. Clio’s compulsive need to be believed, especially regarding the haunting at Edgewood Drive, mirrors her lifelong experience of being dismissed in a family that preferred silence over exploration of pain.

She is also shaped by her dependence on her father and by the subtle ways she absorbs others’ judgments about her impulsiveness and emotional volatility. As the haunting escalates, Clio’s arc transforms into a confrontation with inherited instability, the unreliability of memory, and her fear of becoming another version of her mother.

Ultimately, she emerges as a survivor who learns that facing the darkness within herself is more harrowing—and liberating—than facing any demon inhabiting the house.

Alexandra Barnes

Alexandra Barnes remains a shadowy presence whose influence permeates every character’s life and every corner of the haunted house. Through her memoir, Demon of Edgewood Drive, she constructs a mythology that is both a cry for help and a dangerous distortion, blurring the line between supernatural terror and untreated mental illness.

The contradictions in others’ stories about her—devoted mother, erratic monster, victim of injustice, architect of chaos—mirror the way trauma splinters identity. Alexandra’s belief in the demon becomes a metaphor for her inner torment, and her obsessive return to the house reveals a woman trying to reclaim power in the only place she ever felt both chosen and cursed.

Her love for her daughters is real but warped by fear, instability, and the pressure she places on Clio in particular. In death, Alexandra becomes even more enigmatic, her annotations and warnings re-animating old wounds.

Whether she was possessed, delusional, or both, her legacy is a haunting that her daughters must either inherit or break free from.

Leda Barnes

As the eldest sister, Leda carries the burden of responsibility so heavily that it becomes part of her personality—controlled, polished, authoritative, and weary. She positions herself as the rational one in contrast to Clio’s volatility and Daphne’s nonchalance, but her tightly wound exterior hides profound resentment.

Leda paid the highest emotional cost for growing up under Alexandra; she became a parent long before she should have, and her drive for order comes from a childhood marked by chaos. Her hostility toward the funeral, toward the house, and toward Clio’s involvement in both reflects not callousness but terror that past horrors will re-surface and destabilize the carefully structured life she’s built.

Her concealed memory of seeing the demon as a child, and her lie about the burn that allowed her to escape the house long ago, reveal a woman who copes by burying truth rather than facing it. Leda’s arc ultimately softens her rigidity as she admits the weight she has carried, allowing her to reconnect with her sisters in painful but necessary honesty.

Daphne Barnes

Daphne, the middle sister, serves as a buffer between Leda’s rigidity and Clio’s volatility. She presents herself as calm, funny, and carefree, but her humor and irreverence disguise a deep well of hurt.

Daphne’s identity is shaped by being overlooked: not the responsible eldest, not the emotionally consuming youngest, she learned to keep the peace and stay out of the line of fire. Her empathy toward Clio, even when they argue, shows how much she recognizes herself in her sister’s struggles.

Yet her outburst during therapy, where she admits long-suppressed jealousy and anger, reveals how much she has absorbed silently. Daphne’s relationship with the house is conflicted—she believes in family love over supernatural horror, but the haunting forces her to confront that her optimism was also a coping mechanism.

In the end, Daphne emerges as the emotional bridge of the family, grounded enough to handle the sale of the house but honest enough to acknowledge the past cannot be healed by pretending it wasn’t terrifying.

Amy

Amy occupies an uncomfortable position—stepmother, mediator, and bystander. She tries to keep the peace, but her flustered avoidance when Clio questions the timeline of her relationship with Clio’s father reveals her complicity in rewriting family history.

Amy exists in a space between sympathy and self-preservation; she cares about Clio but never truly sees her. Her discomfort highlights the ways adults often choose convenience over truth, and her presence accentuates the emotional isolation the sisters experienced in their divided household.

Tommy

Tommy, Leda’s husband, serves as one of the few stable and consistently compassionate figures in Clio’s life. His warmth, humor, and grounded nature contrast with the Barnes family’s intensity, making him an accessible emotional anchor.

He sees Clio clearly—both her flaws and her needs—and refuses to treat her like a problem to be managed. His decision to accompany her to the funeral and his steady presence throughout the book showcase a loyalty that is neither performative nor conditional.

Tommy’s openness softens Leda’s edges and provides Clio with a model of healthy emotional behavior, offering glimpses of the support she has rarely felt from her own family.

Austin

Austin represents both a tether to the ordinary world and a gateway into Clio’s complicated past. A childhood acquaintance turned unexpected confidant, he becomes someone she can reveal her messy, frightened, and unfiltered self to.

Austin is not a savior; he is flawed, grieving, broke, and uncertain about his life. But his honesty and vulnerability allow Clio to feel seen rather than managed or dismissed.

Their relationship grows from chaotic attraction into something humanizing, built on shared imperfections rather than fantasy. Austin’s willingness to believe her, even if only partly, provides Clio with a small but significant refuge from the gaslighting she experiences elsewhere.

Roy

Roy is one of the most unsettling human figures in the story because his earnest belief in the supernatural blurs the boundary between mentor and manipulator. His partnership with Alexandra and continued involvement with the house suggest a man drawn to darkness both out of fascination and misguided loyalty.

Whether he is deluded, opportunistic, or genuinely spiritual, his presence deepens the ambiguity surrounding Alexandra’s experiences. His gruesome discovery in the attic casts him as another victim of the house, yet his earlier silence, omissions, and secrecy leave lingering questions about how much he contributed to Alexandra’s destruction.

Roy embodies the dangers of obsession: he may have cared, but his need to validate the supernatural overshadowed the real human suffering in front of him.

Dawn

Dawn offers an outsider’s perspective, a local who saw Alexandra not as a villain or a prophet but as a troubled woman in pain. Her empathy, tempered by realism, provides Clio with a glimpse of what Alexandra might have looked like to someone without history or resentment.

Her recollection of Alexandra on the day she died humanizes a character otherwise filtered through trauma and myth. Dawn’s warmth, contrasted with her blunt assessments, reflects the novel’s theme of how truth and compassion can coexist, even when we cannot fully understand someone’s suffering.

Themes

Family Trauma and Cycles of Harm

Clio’s story in Play Nice unfolds amid a family history shaped by secrecy, fear, and conflicting narratives, and this theme saturates the novel’s emotional core. The Barnes sisters inherit not only a haunted house but also the lingering emotional wounds created long before they were old enough to understand them.

The trauma does not present itself in grand declarations but in the ways the sisters flinch at certain memories, recoil from conversations about their mother, and instinctively assign blame to one another whenever the past resurfaces. Clio’s father attempts to erase Alexandra’s presence by burying photo albums, manipulating memories, and asserting that Alexandra was unstable, yet his silence only intensifies the confusion surrounding their childhood.

The more Clio revisits Edgewood, the more she realizes that trauma is rarely a single event; it is a chain reaction, passed from one person to the next through avoidance, resentment, and denial. This becomes clear in the explosive therapy session, where years of suppressed pain spill over: Daphne admits to hatred she never intended to voice, Leda reveals terror she pretended never existed, and Clio confronts the possibility that her own emotional volatility reflects the very patterns she feared inheriting from Alexandra.

The haunting amplifies these fractures, pushing the sisters and their father toward their breaking points, but the real terror lies in recognizing how deeply each of them is shaped by the ghosts of their upbringing. By the end, the family does not magically heal; instead, they begin to acknowledge that trauma is something they must face directly rather than bury, and that survival depends not on pretending the past was normal but on finally telling the truth about it.

Identity, Self-Perception, and Inherited Roles

Clio’s identity is in constant negotiation throughout Play Nice, shaped by the expectations imposed on her by her family, the fashion world, and the looming shadow of her mother’s legacy. Her sisters view her as impulsive, sheltered, and overly attached to their father, while her father sees her as dangerously similar to Alexandra.

These impressions press against her own sense of self, creating an internal tug-of-war that intensifies whenever she confronts the haunted history of Edgewood. Much of Clio’s self-doubt stems from the roles she was assigned in childhood: the messy one, the dramatic one, the one whose memories were dismissed.

As an adult, her social circle reinforces this uncertainty, treating her emotional fragility as entertainment until she becomes a spectacle during her haunted-house livestream. Clio’s growing obsession with the house forces her to confront the possibility that her instincts, her fear, and even her memories may be unreliable, mirroring the doubt that once surrounded Alexandra.

The demon becomes a distorted reflection of this crisis—it responds to Clio’s fear, familiarity, and inherited vulnerability, almost as if it recognizes something in her that she has not yet admitted. Her final confrontation in the attic is less a battle against a supernatural entity than a reckoning with the parts of herself she has avoided: her grief, her anger, her yearning for connection, and her fear of becoming her mother.

When she offers the necklace, it is not an act of surrender but an acknowledgment that she cannot outrun the parts of her identity shaped by Alexandra. Only by accepting these truths can she finally step out of the roles imposed on her and begin defining herself on her own terms.

The Haunting as a Manifestation of Emotional Reality

The presence in Edgewood is frightening, physical, and violently unpredictable, yet the novel uses the haunting to mirror emotional truths rather than simply frighten. The house reacts to conflict, resentment, secrets, and grief with a precision that suggests it is fed by the family’s unresolved pain.

It is loudest when Clio is at her most vulnerable, and eerily quiet when she questions her sanity, as though it thrives on the instability passed through the Barnes household. The haunting draws attention to the way emotional wounds linger in physical spaces—how a childhood bedroom can still invoke fear, how a hallway can hold echoes of old arguments, and how a house can feel alive with memories no one was ready to face.

As Clio reads her mother’s annotated memoir, she begins to understand that the haunting is inseparable from Alexandra’s unraveling. Whether supernatural or psychological, the entity responds to loneliness, guilt, and attention, suggesting that the real terror is not the demon itself but what it exposes: the depth of Alexandra’s desperation and the emotional inheritance she left behind.

The climax, where the demon forces the sisters to voice their darkest confessions, demonstrates that fear is not its only weapon; it manipulates their pain to keep them trapped in cycles they never consciously chose. The house becomes a physical embodiment of generational suffering, holding onto pieces of each sister until Clio finally insists on facing what has been ignored.

Even then, the haunting does not fully resolve; it lingers as a reminder that emotional scars are not easily exorcised, and that acknowledging pain is not the same as erasing it.

Sisterhood, Conflict, and Uncomfortable Loyalty

The relationship between Clio, Leda, and Daphne is one of the novel’s most dynamic elements, shifting constantly between irritation, affection, defensiveness, and fierce protectiveness. Their bond is shaped by shared childhood experiences they interpret differently, creating a network of misunderstandings that is both painful and resilient.

Leda carries the weight of responsibility, convinced she must be the stabilizing force; Daphne uses humor and emotional distance to shield herself; Clio occupies the role of the unpredictable youngest sibling. These roles harden over time until they become mistaken for truth.

The sisters often lash out at one another before extending comfort, and their arguments reveal how deeply each feels misunderstood by the others. Yet despite the hostility, the bond between them holds firm in crucial moments—they rush to the house when Clio is hurt, stand beside her in the chaos of the haunting, and confront their shared past with brutal honesty.

Their final scenes show a quieter but meaningful shift: instead of defining one another through past resentments, they begin recognizing the ways they relied on each other to survive childhood. The love between them is imperfect and often messy, but it carries a strength that outlasts the house, the haunting, and the weight of the past.

Through them, the novel shows how sibling relationships can be sources of both harm and healing, and how genuine closeness can emerge only when the truth is no longer feared.

Perception, Truth, and the War Between Narratives

Throughout Play Nice, Clio encounters conflicting versions of the past—from her father, from Dawn, from Roy, from her sisters, and from Alexandra’s own writing. These narratives cannot be reconciled cleanly, leaving Clio suspended between doubt and terror.

The novel examines the burden of trying to determine what is real when every person involved has been shaped by fear, guilt, or self-protection. Alexandra’s memoir complicates everything: it contains truths, distortions, omissions, and desperate attempts to be understood, but determining which parts belong to which category becomes impossible for Clio.

Her father’s insistence that Alexandra was delusional and dangerous is undermined by his own deception and rage. Her sisters’ certainty that the house was never haunted collapses when Leda admits she lied as a child.

Even Clio’s own memories shift as she reads the book, revisits Edgewood, and confronts the demon. The theme highlights the instability of truth when filtered through trauma.

Instead of offering answers, the novel suggests that multiple realities can coexist—emotional truth and supernatural truth, remembered truth and denied truth, the truth that protects and the truth that destroys. Clio’s eventual acceptance comes not from solving the mystery but from recognizing that the past will never be neat, and that believing one narrative at the expense of another only deepens the harm.

Her growth lies in acknowledging the contradictions rather than choosing a single version she can live with.

Letting Go, Survival, and the Cost of Holding On

As Clio moves between her city life, her family’s home, and Edgewood, she grapples with the question of what is worth holding on to—memories, pain, objects, relationships, and even identities. The snake necklace, the book, the house itself all become symbols of her attachment to the unresolved past.

Her father’s insistence on controlling the narrative reflects his inability to release his own guilt or anger, while her sisters’ avoidance shows how letting go can sometimes masquerade as indifference. The demon represents the extreme consequence of clinging too tightly: it feeds on attention, fear, and unresolved emotion, growing stronger the more the family tries to fight or explain it.

Clio learns that survival sometimes requires walking away, not because the past loses significance but because continuing to engage with it causes harm. The final scenes—her refusal to return to Edgewood, her understanding of why the house must be sold, and her new ability to move through life without letting fear consume her—illustrate the difficulty of detaching from something that has defined her for so long.

Letting go does not erase the trauma or the memories; it simply removes the power they once held. In choosing distance, Clio begins reclaiming a future that is not dictated by the demons she inherited, whether supernatural or human.