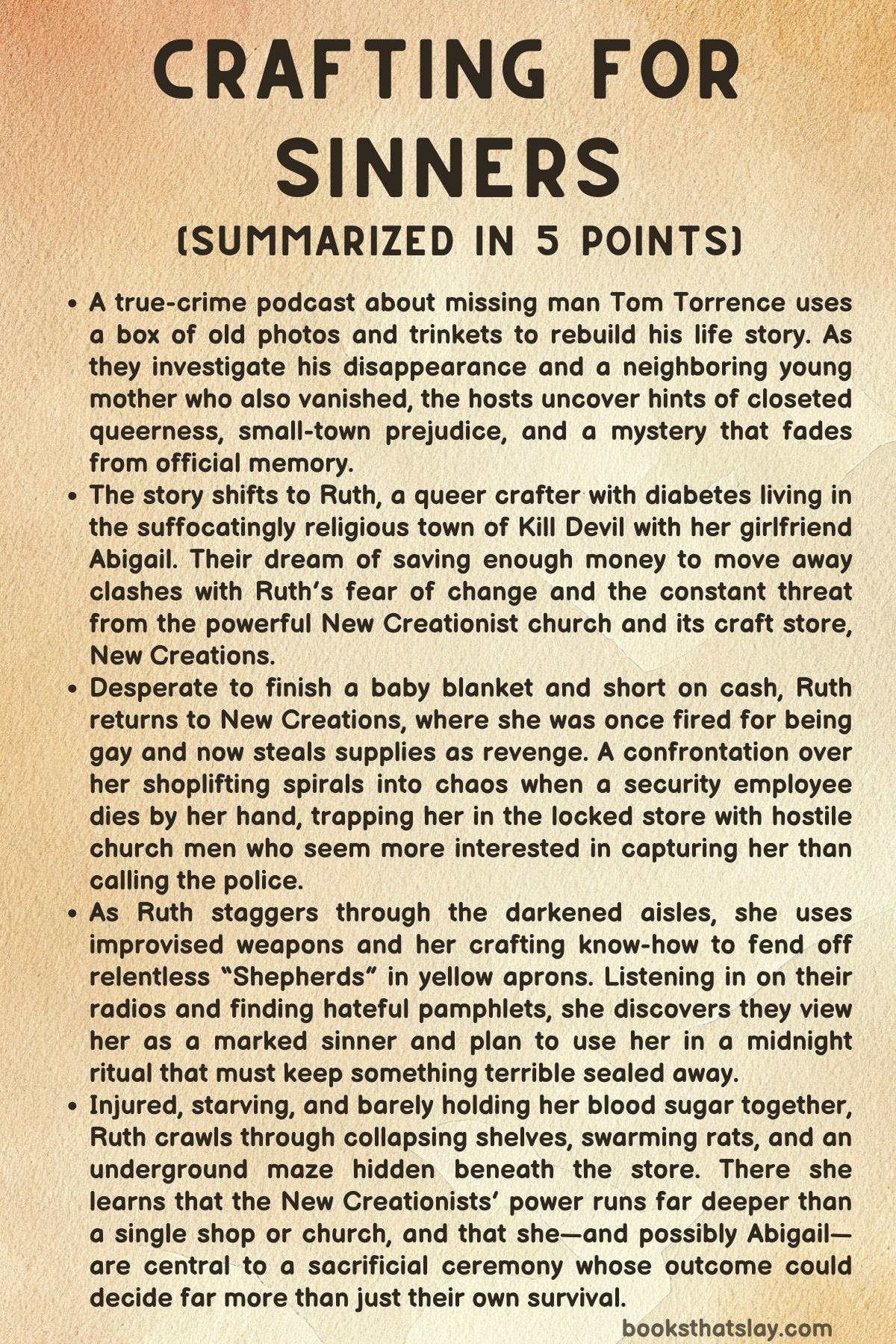

Crafting for Sinners Summary, Characters and Themes

Crafting for Sinners by Jenny Kiefer is a queer horror novel set in rural Kentucky, where crochet hooks, knitting needles, and Bible verses sit side by side with blood, cult rituals, and small-town fear. The story follows Ruth, a diabetic crafter trying to survive in the suffocatingly devout town of Kill Devil with her girlfriend, Abigail.

When a quick trip to the church-owned craft store goes wrong, Ruth is pulled into a night of escalating violence and revelation. As she battles both a fanatical megachurch and something far older and stranger beneath it, the book explores faith, shame, love, and survival in a community built on control.

Summary

The story opens with a true-crime podcast, Cold Cases, Lost Faces, examining the disappearance of Tom Torrence from Lovelace, near Paducah, Kentucky. Tom left his house in the early 2000s as if he meant to come right back: dishes in the sink, laundry mid-cycle, a half-finished check on the table.

He never returned. Years later, a relative of a podcast listener buys the abandoned house at auction and discovers a forgotten box of Tom’s belongings in the basement.

The box is sent to the podcast hosts, Sarah and Lindsey, who use its contents to reconstruct Tom’s life.

Tom appears in photos as a cheerful, sentimental man, smiling through childhood and adulthood, yet official records barely acknowledge he exists. The hosts estimate his age, discover almost no online footprint, and find only a few brief local articles about his disappearance.

Interviewing former neighbors, they hear vague descriptions of Tom as quiet and polite. One man, using the name “John,” finally admits that he and Tom had been secretly dating.

Their relationship, hidden from their conservative community, was tender but vulnerable. John remembers being almost alone in caring what happened to Tom when he vanished, and he suspects homophobia shaped the lack of investigation.

Then the podcast reveals another mystery: about a week after Tom’s disappearance, the young mother next door and her baby also vanished without a trace. The hosts end their episode wondering if the two disappearances are connected and whether the family and Tom fled—or were silenced.

The narrative shifts to Kill Devil, Kentucky, where Ruth, a talented crafter with diabetes, lives with her girlfriend Abigail. Their town is dominated by the New Creationists, a powerful megachurch that owns the craft store New Creations.

Ruth is racing to finish a custom baby blanket for a client who suddenly demands a larger size on an overnight deadline. The pay is crucial for the couple’s “moving fund” jar, their hopeful escape from the town’s hostility.

Abigail is increasingly anxious about rising homophobia and violence, desperate to leave. Ruth loves her but is secretly afraid of change and worries that leaving might eventually pull them apart.

When Ruth runs out of yarn late at night, she realizes the only place to get more is New Creations, where she once worked before being fired for being in a relationship with a woman. Since then, she has resorted to quietly shoplifting craft supplies from the store as a personal act of revenge against the people who judged and discarded her.

Just before she leaves, two unnervingly serene church missionaries appear on her porch, delivering a pamphlet and a strange, ominous religious line tinged with blood imagery. They arrive on foot, without a car in sight, and leave Ruth rattled enough that she calls Abigail from the car to make sure they are truly gone.

At New Creations, the parking lot is eerily empty. Ruth slips inside wearing her ex-fiancé Charlie’s oversized sweatshirt, intending to hide yarn underneath.

The store is filled with aggressively religious décor, all scrubbed in piety and control. Ruth pockets skeins of yarn and a pair of ultra-sharp carbon fiber knitting needles, but a man in a yellow apron—a security worker she mentally labels a “Mustard Seed”—confronts her.

He informs her that the store has enough footage of her past thefts to charge her with a serious crime and demands she come with him. When she tries to flee, she discovers the front gate has been locked.

In the struggle that follows, she accidentally drives a knitting needle into his eye and brain. He worsens his own injury by pulling it out and dies in a horrific scene, leaving Ruth soaked in his blood and in shock.

She tries to get help but quickly realizes the store is locked down specifically to keep her in. Another Mustard Seed calmly escorts her to a classroom, confiscates her hidden yarn, and offers her a brownie as her blood sugar drops.

While he searches her, his headset crackles to life. Ruth hears a voice insist that she be “contained,” calling her “special and precious” and explaining that “it won’t work if she’s dead.” That chilling line tells her the church wants more from her than justice for shoplifting or even the accidental killing.

Terrified, Ruth attacks him, breaks free, and escapes into the darkened store.

From there, the night becomes a brutal, improvised war inside New Creations. Ruth discovers that obvious weapons have been removed from the shelves, that the cameras track her every move, and that the Mustard Seeds are not just employees but zealots following orders from a leader named Gideon.

She uses cash drawers, cleaning sprays, mirror shards, wire cutters, and even super glue as weapons. She blinds her former manager Christopher, battles a huge cultist who has been spying on her home, and sabotages the store’s faulty wiring to knock out lights and security cameras.

She also finds a strange vial of dark liquid and a church pamphlet encouraging people to report “lost sheep”—including homosexuals—to “Noble Shepherds” wearing golden crook pins. The “intensive workshops” hinted at in the pamphlet are clearly more sinister than church retreats.

Listening in on the cult’s radio channel, Ruth learns that Gideon and the other elders see her as a necessary “sacrifice” in a ritual that must be completed before midnight to maintain a supernatural “seal.” They claim that failure will release something terrible into the world. Ruth briefly considers killing herself to sabotage their plan but refuses to abandon Abigail to future danger.

Her fight becomes not only about escape but about destroying the people who want to use her body and blood.

The struggle escalates when Ruth is attacked among the shelves, swarmed by rats, and forced to climb rusted beams to escape. She causes a massive shelf collapse that kills several cultists, including Solomon and possibly Travis, and temporarily convinces the survivors she is dead.

Severely injured and with her blood sugar crashing again, she nearly reaches the emergency exit, only to find it controlled by a keypad lock. Unable to guess the code, she heads for the baking aisle in search of sugar and passes out instead.

Ruth wakes in a new location, having been revived by Charlie with medical supplies and snacks. At first he appears to have saved her, but he soon reveals his true allegiance: he is part of the cult under the name Ahitophel and has deliberately delivered her back into their ritual.

He believes that sacrificing her will send her to heaven and save Abigail’s soul. Ruth attempts to defend herself with a makeshift flamethrower made from a lighter and a squirt gun filled with paint thinner, but Charlie turns it on her.

The stream of fuel backfires, the gun explodes, and Charlie is consumed by fire. Ruth escapes into a network of tunnels beneath the store and church, where she discovers murals, inscriptions, and a family tree linking Gideon to a daughter named Elizabeth, bearing Ruth’s birth year.

Eventually Ruth’s attempts to find help lead her through the woods and into the hands of two police officers. She begs them for assistance, only to realize during the drive that they are part of the cult.

They take her back to the New Creationist church instead of the station, and she is dragged into an underground chamber. There, cloaked figures led by Gideon—who is revealed to be Pastor James—prepare a ritual centered on a small ceramic vessel said to contain a demon.

To keep the entity sealed, they claim they must use the purified blood of a sinner. Ruth is stripped, cut, forced to provide blood and flesh for the newly initiated cultist Travis, then bound on a stone altar and doused again and again with thick sacred oil.

Using the slick coating, Ruth manages to twist out of her bonds and escape into the catacombs and hallways above the ritual chamber. She finds water, cake, and a spare shirt, then hides in the church sanctuary.

When she sees three people guided toward the tunnels, including a woman who sounds like Abigail, she is torn between escaping and going after her. Fear for Abigail wins.

Ruth follows, only to be captured again and hauled back into the ritual chamber.

There, Gideon reveals the final twist: Abigail is actually his estranged daughter Elizabeth, the name on the family tree mural. Abigail was raised in the cult before escaping with her mother, and the New Creationists have always considered her a missing piece of their destiny.

Ruth, bound once more to the altar, fears that Abigail has betrayed her. But when Abigail asks to “atone” by making the first cut, she instead slams the knife into the stone, slashes Ruth’s bonds, and attacks the cloaked figures.

Ruth kicks the table, nearly overturning the ceramic vessel that supposedly holds the demon. She yells for Abigail to break it.

Abigail seizes the jar, fights off Gideon, and throws it to the floor. The impact cracks the stone and the vessel itself.

A chill sweeps the chamber as the cultists panic and scramble to sacrifice themselves in Ruth’s place, desperate to repair what they have broken. Ruth and Abigail use the chaos to escape into the night.

Aboveground, the church and the New Creationist complex begin to collapse as the earth opens up. Fire and molten heat roar from below, swallowing the buildings, cabins, and many of the people.

The wooded hillside becomes a flaming fault line as the two women flee through the forest to the creek near their home.

They wade into the water and watch their old world burn. Later news reports describe the destruction as a sinkhole over a hidden cave system, with no indication of foul play.

Archaeologists uncover hundreds of stolen antiquities beneath the site, but no one proves the church’s role in acquiring them. Ruth and Abigail leave Kill Devil that same night, relocate to a distant city, and slowly build a quiet life together.

The moving fund jar becomes a flower vase, their scars fade, and they try to believe the horror is behind them. Months later, when missionaries appear at their new door with a familiar kind of pamphlet inviting “lost sheep” to the Creator’s flock, Ruth and Abigail are forced to confront the possibility that the cult—or something very much like it—is not entirely gone.

Characters

Ruth

Ruth is the heart of Crafting for Sinners, a woman whose everyday vulnerabilities become the very tools of her survival. At the start, she is defined by small, intimate concerns: finishing a baby blanket for a client, adding cash to the moving fund, managing her diabetes, reassuring a partner who is more visibly anxious than she is.

She is conflict-avoidant, uncomfortable with change, and secretly fearful that leaving Kill Devil might change her relationship with Abigail. That reluctance to leave, combined with her petty but understandable habit of shoplifting from the store that discriminated against her, paints her as flawed but deeply human rather than a standard horror heroine.

Once trapped in New Creations, Ruth’s resourcefulness emerges from desperation. She turns craft tools and store hardware into improvised weapons, exploits her knowledge of the building’s quirks, and constantly problem-solves despite dizziness, blood loss, and low blood sugar.

Her diabetes, initially a quiet background detail, becomes a constant mortality clock that makes every decision sharper and every moment of action more heroic. Emotionally, Ruth moves from wanting to avoid trouble and minimize harm to embracing the necessity of violence in self-defense.

She struggles with guilt over the initial accidental killing, fears damnation in the language the cult uses, and wrestles with the thought of suicide as a way to deny them their sacrifice. Ultimately, she rejects both the cult’s moral framework and her own internalized shame, deciding that her life and her love for Abigail are worth fighting ruthlessly for.

The story turns her from an anxious, underestimated crafter into a physically and morally battle-scarred survivor who understands that she is not a sinner to be purified but a person whose existence exposes the cruelty and hypocrisy of the community that wants to destroy her.

Abigail

Abigail begins as the more visibly frightened half of the couple, keenly aware of the rising homophobia and violence around them. She is the one pushing for escape from Kill Devil, acutely tuned to the danger of staying in a town dominated by the New Creationists.

For a while, she appears primarily through Ruth’s eyes as the loving but anxious girlfriend, the person Ruth fears losing if they move away or if circumstances tear them apart. As the story unfolds, Abigail’s background recontextualizes her fear.

She is revealed as Elizabeth, the daughter of Gideon, the cult leader, whose mother fled with her to escape that world. Her terror, then, is not just about vague bigotry but about specific, inherited trauma and the possibility that her father’s influence might find her again.

When Ruth sees Abigail smiling among the cultists in the ritual chamber, it creates a gut-punch of apparent betrayal that taps into Ruth’s deepest insecurity: that love might be conditional and that Abigail might choose the safety of community over their relationship. The twist of Abigail’s allegiance—asking to make the first cut in order to free Ruth, then attacking the cult—is crucial to her characterization.

She is not the fragile or easily swayed survivor of a cult upbringing but someone who uses the role they expect of her to undermine their power. Breaking the demon jar is both literal rebellion and symbolic rejection of the entire theology used to control her life.

By the end, Abigail stands beside Ruth in flight and recovery, helping build a new life in another city. Yet the missionaries at their new door imply that her past, her family, and the ideology she escaped still cast shadows.

Abigail represents how trauma and inheritance shape fear, but she also embodies the possibility of choosing love and defiance over blood ties and indoctrination.

Gideon (Pastor James)

Gideon, known publicly as Pastor James, embodies the respectable face of small-town religious authority and its monstrous underside. On the surface, he is the charismatic leader of the New Creationists, a figure whose church and store define the moral and economic center of Kill Devil.

Underneath, he is architect and inheritor of a multigenerational cult that justifies torture, murder, and cannibalism as holy acts designed to keep a demon sealed away. His belief system is not merely a cover for sadism; it is portrayed as a sincere, fanatical worldview in which he and his line are stewards of a cosmic burden.

The mural with his family tree and the empty circle for Elizabeth anchors him in a lineage of patriarchal control and sacrificial logic, treating children as pieces in a religious machine. Gideon’s rhetoric about purity, sacrifice, and sin allows him to target people like Ruth—queer, isolated, disowned by family—while framing their deaths as redemptive.

He genuinely thinks he is saving souls while committing atrocities, which makes him more chilling than a purely cynical villain. His paternal relationship to Abigail is particularly revealing.

Rather than showing regret for the wife and child who fled him, he sees Abigail as a lost inheritance, a tool that should return to his flock. He tries to recruit her back into his power structure, assuming that blood and ideology will outweigh her chosen life with Ruth.

When Abigail turns on him and breaks the jar, Gideon’s control collapses, and his entire project is literally swallowed by the earth. In the end, he represents how institutional religion can become a vehicle for intergenerational violence, using the language of salvation to sanctify domination and cruelty.

Charlie (Ahitophel)

Charlie, Ruth’s ex-fiancé, is a study in twisted love and religiously fueled control. At first, he exists in the narrative only as a memory attached to an oversized sweatshirt, a relic of Ruth’s pre-Abigail life and of the more conventional path she might once have been expected to follow.

When he reappears physically, he initially plays the role of savior, administering Glucagon, feeding her sugar, and leading her away from danger. This apparent rescue is tainted almost immediately by his calm explanation that he revived her only to deliver her alive to the sacrifice.

Charlie’s actions are driven by a warped sense of care: he claims to have nominated Ruth because he loves her and wants to save her soul from sin, genuinely believing that her brutal death will guarantee her heaven and perhaps rescue Abigail as well. His cult name, Ahitophel, hints at his status within the group as a devout, trusted insider, someone who has embraced the doctrine so thoroughly that personal affection becomes indistinguishable from fanaticism.

The way he quotes scripture, gently but unyieldingly, shows how thoroughly his moral compass has been captured. Even his attempt to burn Ruth alive with the paint-thinner gun is framed, in his mind, as an act of mercy aligned with divine will.

The explosion that maims him feels like a violent recoil of the universe against his self-righteous certainty. Charlie’s character illustrates how religious ideology can weaponize intimate relationships, turning an ex who might have been a source of nostalgia or regret into an existential predator convinced that destruction is love.

Sarah and Lindsey

Sarah and Lindsey, the hosts of the true-crime podcast Cold Cases, Lost Faces, frame Crafting for Sinners with a different lens on vanished people and community neglect. They are not part of the Kill Devil story directly, but their investigation into Tom Torrence’s disappearance and their narrative style connect personal tragedy to media consumption.

As podcasters, they embody the contemporary urge to turn trauma and unresolved loss into serialized entertainment and advocacy mixed together. Through their research and commentary, they highlight how certain lives—like Tom’s, a closeted man with little official documentation—are easily erased or ignored by institutions.

Their decision to pursue the story despite sparse records and public indifference implicitly critiques the same sort of apathy that allows a cult like the New Creationists to thrive under the radar. They are outsiders trying to reconstruct a life from scraps, but they are also part of an audience-driven culture that consumes such stories.

In contrast to the New Creationists, who destroy and conceal evidence, Sarah and Lindsey work to uncover and memorialize it. Their presence in the book suggests a world beyond Kill Devil in which people care about vanished queer lives, even if that care is mediated through the microphone.

Tom Torrence

Tom Torrence is a haunting figure whose absence shapes the opening of Crafting for Sinners. Everything readers learn about him comes secondhand, through photographs, mundane artifacts, and the voices of others.

The image that emerges is of a cheerful, sentimental man who cherished small things, smiled in photos, cooked well, and quietly cultivated a secret love in a town unlikely to accept him. The fact that there are no official records of his birth and almost no media coverage of his disappearance underscores his social invisibility.

In life, Tom negotiated the risk of being openly gay in a conservative environment by limiting his world to private date nights and a hidden relationship with John. In death, he becomes a kind of symbol for how queer people in such communities can simply vanish, with authorities and neighbors offering only cursory concern.

His disappearance, paired with the mother and baby vanishing next door, hints at patterns of violence or escape that go unexamined. Tom’s story indirectly foreshadows Ruth’s danger: both are queer people whose communities fail to protect them, and both run into the lethal convergence of secrecy, prejudice, and institutional neglect.

Where Ruth fights and survives, Tom simply disappears into the past, remembered only because some strangers with a podcast refused to let his name fade.

John

John, Tom’s secret boyfriend, adds emotional depth and quiet tragedy to the podcast narrative. He is one of the few people who truly knew Tom, sharing private date nights at his more secluded home where they watched movies and cooked together away from the judgment of Lovelace.

Forced into secrecy by the conservative community, John embodies the long-term strain of living a double life: he navigates the risk of exposure, the loneliness of hiding, and the constant need to protect both his own safety and Tom’s. After Tom vanishes, John is nearly alone in his efforts to find him.

His belief that the police did not take the case seriously because of Tom’s sexuality introduces a crucial theme that echoes in Ruth’s story: official systems treat queer victims as lesser, and this neglect is itself a form of violence. John’s grief is compounded by the knowledge that he cannot easily claim his role in Tom’s life publicly, which means his love and his loss are doubly erased.

He stands as a quiet counterpart to Abigail, another partner who fears losing the woman she loves to a hostile community. Unlike Abigail, John never gets resolution; his presence in the narrative underlines that not every missing person gets an escape or a fiery, cathartic ending.

Christopher

Christopher, Ruth’s former manager at New Creations, represents the everyday face of institutional bigotry solidified into cult enforcement. Years before the night of violence, he fired Ruth for dating a woman, cloaking discrimination in euphemisms about values and traditional beliefs.

When Ruth encounters him again as one of the Mustard Seeds, he has aged but remains firmly within the system, now empowered not just to terminate employment but to physically capture her. His attempts to talk Ruth into surrender blend corporate management tone with religious rhetoric, as he frames coercion and capture as opportunities for redemption.

Christopher genuinely seems to believe he is helping her by bringing her in alive, promising redemption while minimizing her fear and pain. The scene where she nearly kills him but pulls back reveals a contrast between their moral frameworks: he invokes sin and damnation to dissuade her from violence, while she struggles to reconcile survival with her own reluctance to become a killer.

He is not the most fanatical or powerful cultist, but he is a bridge figure showing how a place of employment, run under a religious ethos, can quietly become the infrastructure for something far more sinister. When he promises that another Shepherd will come to collect her, he reveals how interchangeable and replaceable individual enforcers are within the cult’s machine.

Elijah

Elijah, the massive Mustard Seed who watches the woods behind Ruth’s house, is a physical manifestation of the cult’s invasive gaze. Before Ruth recognizes him in the store, he appears as an unsettling presence in her daily life, a stranger repeatedly seen birdwatching in a way that feels more like surveillance than hobby.

This earlier detail transforms, in hindsight, into evidence of long-term stalking and targeting. Once he confronts her in the darkened store, Elijah’s strength and endurance make him feel almost superhuman, an embodiment of the cult’s belief that some Shepherds are Imbued with the Creator’s power.

His near-invulnerability to pain and his calm preaching while he hoists her around the aisles give him an almost monstrous aura. Yet his downfall comes not through divine intervention but through the mundane reality of super glue and panic.

Ruth gluing his hands to his face and hair to his cheek, then tearing free as he thrashes blindly, undercuts his supposed invincibility and highlights how the cult’s myth of Imbuement is both terrifying and fragile. Elijah’s character shows how myth can be grafted onto ordinary brutality, turning a large man with a headset and a vial into an angel of judgment in his own mind and in the fear of his victims.

Solomon

Solomon is one of the more articulate and ideology-conscious cult members, serving as both instructor and strategist. During the rat scene, his calm explanation to Travis about the ritual, the consumption of Ruth’s flesh, and the plan to manipulate Abigail into joining the cult reveals the full predatory logic of their theology.

Unlike some of the more physically imposing Shepherds, Solomon’s menace lies in his intelligence and his capacity to see people as pieces in a long-term plan. He has studied Ruth’s life enough to know about her disowning parents, her lack of nearby friends, and her dependence on Abigail, and he views these vulnerabilities as features that make her an ideal sacrifice.

His willingness to discuss future assignments of wives and sacrifices, including the possibility of killing Abigail next, exposes how routine such brutality has become for him. Solomon’s death under the cascading shelves is a direct result of underestimating Ruth and overestimating the safety of his controlled environment.

The chain-reaction collapse that crushes him symbolizes the sudden implosion of a carefully constructed system toppled by a single desperate act of resistance.

Travis (Nabal)

Travis begins as a younger recruit, someone still asking questions and seeking reassurance about the cult’s most extreme practices. His initial horror at the idea of cannibalism shows that he has not yet fully absorbed the doctrine.

Solomon’s patient indoctrination reveals how the cult slowly reshapes the moral instincts of its members, turning disgust into pride in obedience. Later, Travis is pinned and likely dying after the shelves collapse, yet he ultimately reappears in the ritual room, initiated as Nabal and given the grotesque honor of consuming Ruth’s blood and flesh.

This arc, from uncertain novice to newly named participant in a sacrificial rite, illustrates how quickly a wavering conscience can be subsumed when surrounded by a fanatical community and incentivized to prove loyalty. Travis is simultaneously perpetrator and victim.

He is young and malleable, but he actively chooses to drink and eat from Ruth’s suffering in the name of faith. His presence in the ritual underscores the cult’s ability to reproduce itself across generations, recruiting the next wave of zealots even as the older leadership ages and dies.

Themes

Religious Extremism and Cult Mentality

Religious extremism in Crafting for Sinners is not a background detail but the engine that drives nearly every horror Ruth experiences. The New Creationists present themselves as a wholesome megachurch with a family-friendly craft store, Bible language, and friendly missionaries, but their theology is fundamentally built on domination, fear, and blood.

Their doctrine of “purity” justifies everything from workplace discrimination and harassment to murder, cannibalism, and the theft of sacred artifacts. The language they use is deliberately comforting and familiar—Shepherds, lost sheep, workshops, redemption—masking a structure where individual conscience is replaced by blind obedience to Gideon and the hierarchy.

The fact that Ruth’s parents are members yet “disown” her for her sexuality shows how faith has been reshaped into a tool that demands the sacrifice of compassion itself. Underground, the church’s true nature becomes literalized in the tunnels full of bones, the altar, and the demon jar: the pious facade above and the brutal reality below are part of one system, not opposites.

The cult’s willingness to torture and eat their victims confirms that their “Creator” is really a reflection of their own appetite for power and violence. Yet the book also suggests that extremism is contagious and adaptive; even after the church and store collapse into the burning sinkhole, pamphlets and missionaries appear in Ruth and Abigail’s new city.

The belief system has already spread beyond one physical site, carried by people who sincerely think they are saving souls. In this way, the novel links religious extremism to a broader cultural pattern: institutions that promise safety and moral certainty often rely on hidden systems of control, scapegoating, and ritualized harm that are much harder to extinguish than a single building or leader.

Queer Identity, Homophobia, and Survival

Queer identity shapes almost every choice Ruth and Abigail make, and homophobia shapes almost every danger that stalks them. From the beginning, Ruth’s firing from New Creations for dating a woman signals that the community’s “values” are explicitly hostile to her existence.

The pamphlet listing homosexuals among the “lost sheep” to be reported, and the planned “intensive workshops,” reveal a structure designed to erase queer people under the guise of care. The cult targets Ruth precisely because she is queer: her parents have abandoned her, she has no socially sanctioned family ties, and the town’s conservative culture ensures that most people will not question her disappearance.

Solomon’s explanation to Travis that Ruth is a “perfect” sacrifice because no one will look for her, and that Abigail can be emotionally manipulated afterward, exposes how homophobia creates vulnerable bodies that systems of power can exploit. Ruth’s sexuality is never portrayed as her flaw; instead, the flaw lies in a community that treats love between women as a stain to be washed out with blood.

At the same time, queer survival in the novel is not only physical escape, but the stubborn insistence on love and pleasure in the face of hatred. Ruth and Abigail’s “moving fund” jar, their domestic life, and Ruth’s crafting are all small acts of building a future that the church insists should not exist.

The cult’s attempt to recast Abigail as a dutiful daughter and Ruth as a necessary sacrifice dramatizes how homophobic systems try to pull queer people back into prescribed roles. When Abigail turns Gideon’s ritual against him and uses the knife to free Ruth instead of killing her, the book offers a powerful counter-image: a queer woman rejecting the script written for her and choosing her partner over biological family and doctrine.

Survival here is not just about living through the night; it is about claiming the right to define one’s own worth and relationships in a world arranged to deny that right.

Control of Bodies, Consent, and Sacrifice

Throughout Crafting for Sinners, conflict revolves around who has the right to decide what happens to a body, especially a “sinful” body. Ruth’s body is subject to constant unwanted control: she is grabbed by store employees, searched, locked in rooms, hooded, tied down, and cut.

The cult’s theology reframes all of this as “saving” her, insisting that her death will cleanse her soul, even though she explicitly wants to live. Their reversed communion—eating her flesh and drinking her blood as proof of devotion—turns the language of sacrifice into justification for violating every boundary she has.

Consent is systematically erased; her no can never matter in a system that treats her as an object to be purified. Her diabetes adds another layer, because it makes her physically dependent on sugar and medical help that others can withhold or grant.

The cult uses this vulnerability first as leverage—reviving her so she can still be sacrificed—and later overlooks it in their arrogance, which gives her crucial openings to escape. The body is also a battleground between sacred and profane from the cult’s perspective: they pour perfumed oil over her until she is drenched, a ritual that is supposed to sanctify her for death.

Yet that same oil becomes her means of sliding free from their grasp and escaping the altar. Over and over, substances applied to or taken into the body—glue, paint thinner, sacred oil, brownies, candy, the demon’s “seal” in blood—become contested tools.

The novel suggests that any ideology claiming ownership over another person’s flesh in the name of salvation is inherently violent, no matter how beautiful its language. Ruth’s repeated acts of self-triage—gluing her wounds, splinting her limbs, forcing herself to climb despite pain—mirror a deeper assertion of bodily autonomy: even when surrounded by people who insist her body exists for their purposes, she keeps reclaiming it as her own.

Domesticity, Crafting, and Weaponized Femininity

Crafting and domestic work in Crafting for Sinners are more than cozy background details; they are instruments of both oppression and resistance. Ruth is a crafter by trade and passion, making baby blankets and handmade objects that symbolize care, home, and nurturing.

The New Creationists’ craft store is built on that same aesthetic of wholesome domesticity—yarn, decor with religious slogans, floral arrangements—but it uses those symbols to reinforce rigid gender roles and conservative family structures. The store markets a vision of femininity centered on service, submission, and beautifying the home in alignment with church doctrine.

Yet the narrative consistently shows how these tools of “softness” can be turned into weapons. Ruth shoplifts yarn as quiet rebellion, then grabs carbon fiber knitting needles, wire cutters, yard signs, mirrors, and even hot glue guns as literal weapons during her fight for survival.

The items that are supposed to keep women busy, polite, and productive become the means by which she injures or kills her captors. The cult’s women, starved and controlled, represent another side of domesticity: they are denied food, autonomy, and space, expected to accept their husbands’ rituals and authority in exchange for spiritual security.

Their bodies are visibly worn down in service of a household and religious machinery they do not control. When they stand at the property line unable to cross, it underscores how domestic confinement has been turned into a kind of invisible cage.

Ruth’s crafting, however, retains a trace of freedom. The baby blanket she rushes to finish, the moving fund jar on the counter, and her careful repairs to her own injured body all use the logic of making and mending to protect her queer household.

The story suggests that domestic tools can serve two masters: they can uphold oppressive ideals when controlled by institutions, or they can become devices of self-preservation and defiance when claimed by the people those institutions want to keep small.

Surveillance, Institutions, and Community Complicity

Surveillance in the novel operates through cameras, gossip, police power, and religious authority, forming a network that leaves Ruth almost nowhere to turn. Inside New Creations, cameras track her every movement; employees speak with headsets to distant supervisors; obvious weapons have been removed in advance.

This shows that the church anticipated resistance and built an environment where any deviation could be quickly contained. The pamphlets urging congregants to report “lost sheep” expand that surveillance into the town itself, recruiting ordinary people as informants.

The police are not neutral outsiders; they are cult members who stage a rescue only to deliver Ruth back to the ritual chamber. Their decision to shove her car into the river and intercept her on the only road off the property demonstrates how thoroughly local institutions have been captured.

Even healthcare, usually a site of help, becomes a lie: the officers promise a nurse at the station while fully intending to sacrifice her. The true-crime podcast at the beginning and the sanitized news reports at the end add another layer: information can be filtered and repackaged so that the public sees missing people as mysteries or tragic accidents rather than the result of systemic hate.

Tom Torrence’s queerness keeps his case marginalized; the cult’s destruction is framed as a geological accident, erasing the human malice that caused it. The book therefore suggests that complicity is not just active participation in evil, but also the choice to accept official stories without questioning who benefits from them.

Surveillance and institutional capture make resistance risky and lonely; Ruth recognizes that calling the police may make things worse, and she knows most neighbors will instinctively trust the church over her. Her survival is all the more remarkable because it requires seeing through the respectable faces of authority and trusting her own perception even when every formal structure insists that she is the problem.

Love, Loyalty, and Chosen Family as Resistance

Love in Crafting for Sinners is consistently opposed to the cult’s version of “love,” which demands sacrifice, obedience, and the denial of self. Ruth and Abigail’s relationship is ordinary in its routines—sharing a home, worrying about bills, arguing about moving—but extraordinary in its resilience under pressure.

Abigail’s fear of rising homophobic violence and Ruth’s quiet dread of change create tension early on, yet both remain committed to building a life where they can be safe together. The cult tries to weaponize love in several ways: Gideon frames his fatherhood to Abigail as spiritual care, Charlie claims that nominating Ruth as a sacrifice is an act of love meant to save her soul, and the doctrine promises eternity in heaven as a reward for killing or dying according to the ritual.

In each case, “love” is redefined as compliance with harmful demands. By contrast, Ruth’s love for Abigail grounds her choices.

When she hears that Abigail may be targeted next, her survival instinct fuses with a determination to stop the cult from ever reaching her. She refuses suicide because it would leave Abigail alone and defeated, and later, in the ritual chamber, she urges Abigail to break the demon jar not out of abstract heroism but from a shared desire to escape together.

Abigail’s loyalty is tested most directly when she stands in the ritual room with the knife. The cult expects her to prove her devotion to her father by hurting Ruth.

Instead, she uses the moment to free her partner and attack the men around her. That decision breaks the pattern seen in Tom Torrence’s story, where a secret queer relationship is separated by violence and indifference.

The novel closes on Ruth and Abigail building a new home elsewhere, turning the moving fund jar into a flower vase, transforming a symbol of escape into one of rootedness. Even when the pamphlet appears at their new door, implying that danger may return, the reader has seen that their shared loyalty has already defeated a whole community’s attempt to annihilate them.

Love, treated as mutual protection and respect rather than control, becomes the strongest force opposing the cult’s theology of sacrifice.

Trauma, Aftermath, and the Persistence of Evil

The horrors Ruth endures do not evaporate once she and Abigail escape the burning grounds of Kill Devil. The book’s final sections emphasize how trauma lingers and how evil adapts.

Ruth’s body bears scars from bites, cuts, burns, and self-inflicted glue repairs; her diabetes management has been pushed to the edge repeatedly. These physical marks reflect psychological wounds: she has been betrayed by an ex-fiancé, targeted by her own parents’ church, hunted by police, and nearly eaten in a ritual.

The move to a distant city and the building of a quieter life are acts of healing, but the narrative does not pretend that such experiences can be neatly sealed away. The news coverage of the disaster contributes to this difficulty by rewriting events in palatable terms.

The story of demon jars, cannibalistic rituals, and institutional corruption is replaced with talk of limestone cave systems, sinkholes, and mysterious artifacts. Without public acknowledgment of what truly happened, Ruth and Abigail are left to carry the reality alone, another form of isolation.

The archaeologists’ discovery and repatriation of stolen artifacts also suggest that the cult’s crimes occurred on a global scale, affecting communities that will never know why their sacred objects were misused. The missionaries who appear at Ruth and Abigail’s new door encapsulate the idea that the underlying ideology has survived.

Whether they are direct remnants of the New Creationists or a similar group using the same rhetoric matters less than the implication: structures that demonize certain people as “lost sheep” and promise a path to purity are always ready to reappear. The pamphlet is a small, almost mundane object, but it carries the echo of basements lined with bones and altars slick with oil.

Trauma, then, is not only personal but also cultural; it is sustained by narratives that refuse to name harm and by institutions eager to rebuild under new branding. Yet the ending also implies that acknowledging what happened—between Ruth and Abigail, and for the reader—creates a kind of quiet resistance to that erasure, even if the world at large prefers a comforting lie.

Stories, True Crime, and Whose Suffering Counts

The framing of Crafting for Sinners with the true-crime podcast and later news reports invites reflection on how stories about violence are told, consumed, and forgotten. The podcast hosts present Tom Torrence’s disappearance as a puzzling cold case, pieced together from trinkets in a box and fragmentary newspaper clippings.

They emphasize the eeriness of his vanishing house, the coincidence with the young mother and baby next door, and the lack of records that make him almost a ghost. Yet their investigation remains at a distance; Tom is reconstructed through photos and reminders, and his probable queerness is hinted at rather than fully honored as central to his vulnerability.

The podcast format turns his life and likely death into content—compelling, but ultimately something listeners can switch off. Meanwhile, the present-day narrative around Ruth shows how easily another queer person could have become a similar story, or not a story at all.

If the cult had succeeded, her disappearance might have been dismissed as a troubled woman running off, a tragic accident, or another unsolved mystery. When the New Creationist complex collapses, journalists focus on geological phenomena and archaeological finds, not on who enabled a deadly cult to thrive in a small town.

The contrast between the sensational hook of the podcast and the bland neutrality of the later news demonstrates how media shapes whose suffering is seen as meaningful. Some lives become entertainment retroactively; others are erased under vague language and official denial.

The book suggests that the most accurate stories about violence often remain in the memories of survivors and their communities rather than in formal narratives. Ruth and Abigail choose not to publicly expose everything, partly from exhaustion and fear, which makes sense on a human level but also ensures that much of the truth stays hidden.

The reader, having seen inside the tunnels, rituals, and personal stakes, is placed in a position unlike that of the podcast audience: we cannot pretend that what happened is just a spooky mystery. The novel thus asks a quiet but pointed question about the ethics of consuming stories of harm and the responsibility to see the structural forces—homophobia, religious extremism, institutional complicity—behind individual tragedies.