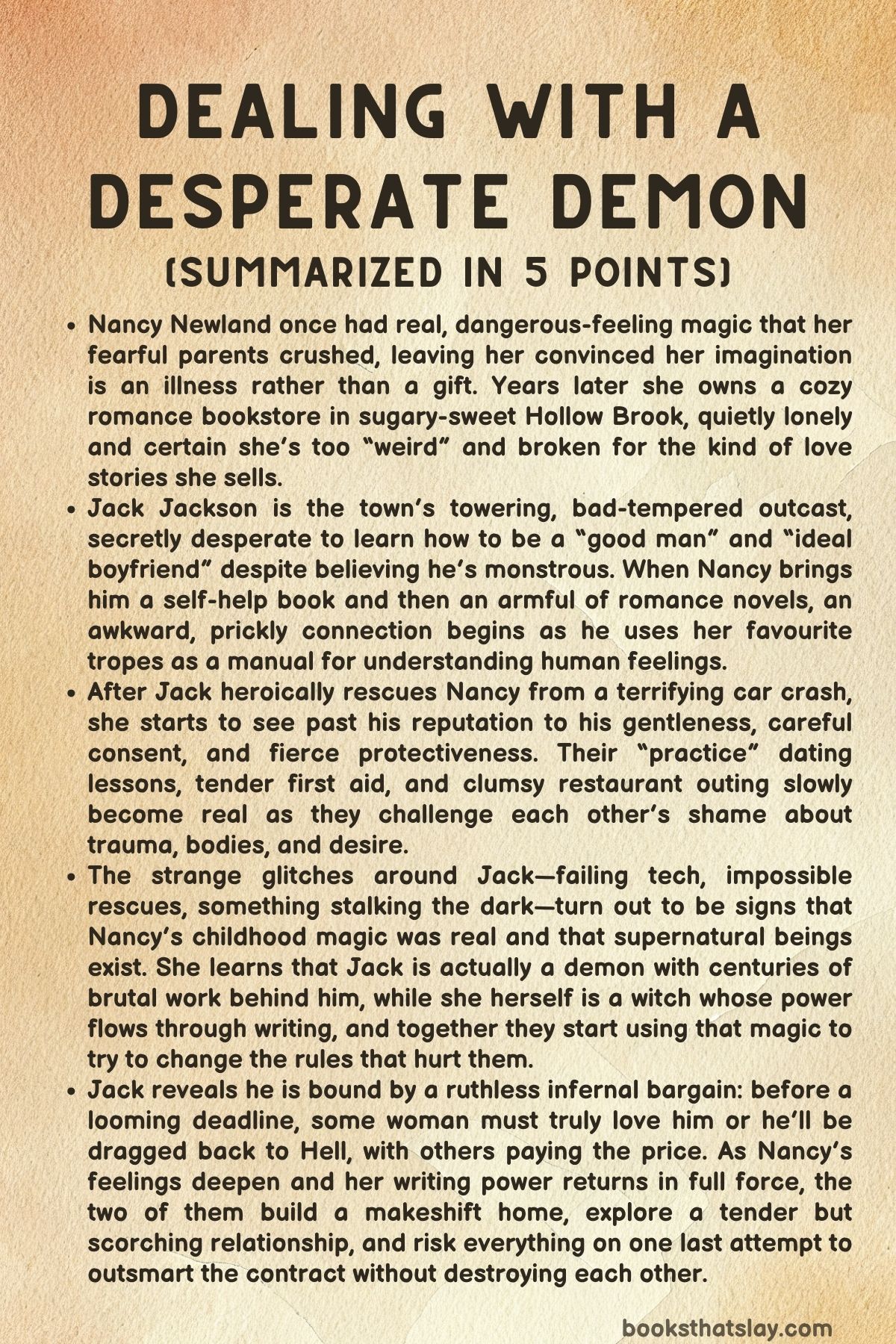

Dealing with a Desperate Demon Summary, Characters and Themes

Charlotte Stein’s Dealing with a Desperate Demon is a paranormal small-town romance about a witch who thinks her magic and her mind were broken in childhood, and the demon who has spent years trying to be worthy of her. Nancy now runs a cosy bookshop and tries to live quietly, but her buried power, old fears, and love of romance stories all come roaring back when Jack Jackson, the town’s notoriously scary giant, walks through her door.

It’s funny, sad, tender, and very steamy, but at its core it’s about consent, safety, and being loved exactly as you are. It’s the 2nd book in The Sanctuary for Supernatural Creatures by the author.

Summary

Nancy Newland once had real, spectacular magic. As a lonely teenager, she wrote stories that changed reality: animals talked, furniture transformed, and her words bled into the world.

She poured her deepest wish into a fairy tale about a soul mate, beginning, “Once upon a time, there was a prince who wasn’t,” unknowingly calling a demon across the dark. Her strict, frightened father stormed in, snapped her treasured pen, and the magic vanished with a crack.

Branded unstable and later institutionalized for “hallucinations,” Nancy learned to distrust her senses and her own imagination.

Years later, Nancy runs Better Off Read, a whimsical bookstore in the saccharine town of Hollow Brook. She lives quietly with her pug, Popcorn, surrounding herself with romance novels and fantasy she no longer lets herself believe in.

One day Jack Jackson, the town’s huge, famously unpleasant recluse, walks into her frilly little shop. Startled, she nervously references an embarrassing newspaper story about him, and he flees.

After he leaves, she discovers the book he had been reading: a lavender volume called How to Be the Ideal Human Boyfriend. Realizing he’d come, mortified, to ask for help being better, she is flooded with guilt and decides to bring the book to his remote cabin as a peace offering.

From the outside his place is a horror shack: chains on the porch, door ajar, spooky woods. Inside, Nancy finds a nest of softness—fairy lights, kitten art, hand-knitting, and gentle, romantic VHS tapes.

While she is absorbing this, Jack appears from the shower in a too-small towel. Both are mortified.

Jack, sure she’s mocking him, erupts in shame and fury over the boyfriend book and the idea that he needs a manual to be worthy of anyone. Nancy bolts, thinking she has ruined everything.

On the way home, the woods darken unnaturally, something grotesque steps in front of her car, and she crashes. Hanging upside down in the wreck, she is certain she will die—until Jack arrives, rips through metal with impossible strength, and carries her out.

He drives her back to town, blaming himself and refusing thanks for what he calls basic decency. At the shop, he kneels to examine her injured ankle, asking permission before every touch and bandaging her with surprising gentleness.

Nancy, shaken and suddenly very aware of him, loads him up with romance novels as reference material. Jack reads all six thick books in a single night.

The next morning, he returns early, armed with a notebook overflowing with questions about consent, height, how “safe assholes” work in romance, and what men are supposed to do if a woman’s father is cruel instead of protective.

Seeing how hard he is trying, Nancy offers to “coach” him through dating. At his cabin she picks out clothes, teaches him how to hug without panicking, and reassures him that his size, beard, and softness are attractive, not monstrous.

Their practice date at the fanciest restaurant in town becomes a turning point: Jack admits he only truly loves desserts and has always hidden that to look tough. Nancy orders almost every dessert on the menu just to watch him enjoy them openly, turning something he is ashamed of into a quiet celebration.

They talk about her time in the hospital, the nightmares of creatures in the dark, and the half-remembered figure who once rescued her from a fire. Jack responds with outrage on her behalf and a promise: next time she falls, he will catch her.

Their pretend romance slides toward something real. An intense hug in his hall, his careful touch on her injured leg, and the way he listens to every word all deepen the bond.

During a blackout at his house, when Nancy panics at shadowy shapes and the urge to write protective words in the air, Jack holds her, believes her fear, and gives her a pen and pad. He tells her to write what she needs as if the magic is real.

She writes “Let me be” three times and feels some of her power and safety return. He is the first person to treat her “weirdness” not as illness but as truth.

Eventually, the secret Jack has been hiding erupts: he is a demon from Hell’s punishment division. Hell is real, organized into departments, and Jack’s job is smashing the worst souls with a giant hammer.

He reveals a towering demon form with horns, black eyes, and a body that could never fit in Nancy’s little shop. His human life, and the Jack Jackson identity, exist because a witch once summoned him with a powerful spell and partially transformed him into a man.

That spell—Nancy’s long-ago story—came bundled with a contract: if the witch tells him she loves him by a deadline, he can keep his human life; if not, Hell drags him back and harms anyone who interfered.

With Jack now switching between human and demon in front of her, Nancy finally accepts that her childhood visions were real, not delusion. They try to use her writing magic to change the pact.

She writes careful lines meant to free him and shield everyone from consequences, but the words melt off the page or set off mocking magical “error” noises. Her trauma, doubt, and tangled feelings keep jamming the spell.

Abandoning clever loopholes, they decide to live the time he has left on their own terms: sharing breakfasts, shopping trips, Christmas decorations, a bed, and eventually sex that is both fiercely physical and deeply tender, with Jack constantly checking in and treating her pleasure as sacred.

Time, however, keeps running out. Hellhounds stalk the town’s edges.

Jack, convinced he is too damaged and frightening to be anyone’s safe forever, decides to break the contract in a way that will minimize harm to Nancy, even if it damns him. In his cabin, with infernal pressure literally shaking the walls, he gives Nancy a heavier pen and begs her to write like the girl who first summoned him.

She finally pens a line that wipes away Hell’s added clauses and returns the bargain to its original shape. The floor splits open.

As he is dragged down, Jack blurts the truth: Nancy is the witch who called him, the lonely girl who wrote about a prince who wasn’t, the one he has loved for years. She shouts that she loves him, but the portal slams shut.

Nancy refuses to let this stand. With only Popcorn and Jack’s semi-alive truck for company, she drives into Hell itself: a maze of grim corridors and petty bureaucracy.

She fights her way to Jack, who at first fears she is a torment invented to torture him. In a drab little room, they argue, then finally speak plainly.

Each admits they tried to set the other free at their own expense. Each confesses the love they kept swallowing down.

Together they escape back to the human world.

There, Nancy recovers the unfinished page from her childhood story. This time she writes with full belief, finishing the tale of the prince who wasn’t with a clear, happy ending: that he and the girl who summoned him get to live the life they choose together.

That ending overwrites the devil’s claim and releases Jack from Hell’s service permanently. In the epilogue, Nancy and Jack attend a New Year’s party with their human and supernatural friends as an openly loving couple.

Later they slip into the woods, where Jack reveals his full demon form. Nancy chooses him exactly as he is—man, demon, protector, partner—the living answer to the wish she wrote as a lonely girl and the future she now embraces without fear.

Characters

Nancy Newland

Nancy is the emotional and magical center of Dealing with a Desperate Demon. As a child, she is a lonely, fiercely imaginative witch whose writing literally reshapes reality, but that power is met not with wonder, but with fear and punishment.

Her parents, especially her father, frame her abilities as mental illness, sending her to an institution and violently cutting her off from the tools of her magic by snapping her beloved pen. That early betrayal shapes her entire sense of self; as an adult she still flinches from her own perceptions, assuming that anything supernatural must be “delusional,” even when her life is full of uncanny coincidences, strange shadows, and a terrifyingly vivid memory of the burning hospital and a mysterious rescuer.

Nancy’s bookstore, Better Off Read, is her attempt to build a softer, safer world inside a harder, crueler one. She dresses in cute outfits, bakes, decorates, and recommends romance novels as if she can keep the harshness of reality at bay with fairy lights and paperbacks.

At the same time, that “wholesome” aesthetic can be a shield; she believes she is the kind of girl men find sweet but forgettable, not someone who could possibly be a demon’s chosen witch or anyone’s great love.

Her arc is about reclaiming both her magic and her right to believe herself. At first she treats her visions and memories as embarrassing symptoms and edits herself constantly in conversation, trying not to sound crazy or needy.

When Jack takes her fears seriously and insists that a good father would have protected her instead of institutionalizing her, he gives her back a frame in which her experiences are valid. His simple command to “write it” using a mundane pen opens the door for her magic to return, and she begins to test the edges of that power again.

The more she writes, the more she realizes that her words still have weight, especially when she writes from a place of honesty and feeling rather than fear. Her growth is not just about becoming stronger magically but also about taking up emotional space: asking questions, admitting desires, and eventually demanding a happy ending not just in fiction but in her own life.

Nancy’s relationship with Jack drives her transformation. At first she reads him through a romance-reader lens, trying to categorize him as a grumpy hero, an enemy-to-lover, or a wounded beast.

Yet the more she interacts with him, the more those tropes break open and force her to confront real vulnerability. She sees his self-loathing, his certainty that he is too monstrous to be loved, and recognizes a reflection of her own belief that she is too “broken” and “crazy” to be safe for anyone.

When she finally storms Hell itself to get him back, she is not playing the role of the rescued princess; she is the author of the story, the witch who refuses the terms of other people’s narratives. By finishing the unfinished summoning tale she wrote as a teenager and writing the words “happily ever after” on her own terms, she heals the original wound: the moment her father broke her pen and called her madness.

Nancy ends the book as a woman who knows she is a witch, knows that her love matters in cosmic terms, and knows that her way of seeing the world was never a sickness, only a different kind of truth.

Jack Jackson

Jack begins the story as the town monster in human clothes: an enormous, grumpy, socially awkward man with a bad reputation and a history of spectacular public embarrassment. He is framed, at first, as an almost urban legend, the kind of guy everyone in a small town thinks they understand.

Underneath that reputation, however, he is a demon executioner from Hell who has spent millennia punishing the worst souls imaginable and has been dropped into human life under a brutal contract that hinges on love. His size, his temper, and his clumsiness are all colored by deep trauma and constant self-policing.

He believes that he is inherently dangerous and unworthy of tenderness, so he tries to manage his desire to be good through research, almost like a scientist: reading a self-help book called How to Be the Ideal Human Boyfriend in secret, bingeing romance novels overnight, and scribbling meticulous notes on how “normal men” behave. This creates the sense of a creature who has studied humanity from the outside and is desperately trying to pass as something he has never been allowed to be.

Jack’s internal conflict is about monstrosity and masculinity. His demon form is huge, horned, and terrifying, but feel-wise, there is little difference between that body and his human sense of himself as “too big,” “too hairy,” “too rough,” and “too much.” His father in Hell and the infernal system he serves are both punitive and rigid, and his human upbringing echoes that toughness-first expectation: big men must be dominant, stoic, and interested in savory steaks, not soft desserts or cozy VHS romances.

He pushes himself into those roles until they break him. Only when Nancy orders every dessert on the menu and watches him drink milk like whiskey, or when she admires his Viking body instead of mocking it, does he begin to imagine a masculinity that includes gentleness, sweetness, and a desire to be held.

His meticulous care with her injured ankle and his instinct to physically interpose his body between her and danger reveal that beneath the horns and the hammer there is a protector whose violence is reserved for true monsters, never for the people he loves.

His emotional arc pivots around worthiness. Jack is convinced that love, especially from someone like Nancy, is something he has to earn by becoming a perfect “human boyfriend” and by completing Hell’s impossible contract.

He measures his progress in painfully literal ways: whether he ruins a date by spilling water, whether he can stay in human form during sex, whether he remembers the right small talk topics. Every failure feels like proof that he is essentially unfit for love.

That is why he decides at one point to break the pact in a way that will send him back to Hell but reduce the danger to Nancy. He would rather be tortured forever than risk her being hurt by demons coming after him.

When the ground opens and he is dragged down, his last words to her are a confession of love that also reveals she has been the witch he was trying to be worthy of all along. Jack’s eventual freedom comes not from perfect behavior but from accepting that he is already the man Nancy chose, horns and all, and that the story was always about the two of them choosing each other, not about him passing a moral exam.

By the end of the book, he allows himself to be both man and demon in front of her, letting his true form exist not as a punishment, but as a body that can be held and loved.

Cassie

Cassie functions as both best friend and magical mentor, embodying the healthy, grounded witch Nancy might have become if she had been believed and nurtured instead of institutionalized. In everyday life she is the kind of friend who senses Nancy’s distress over the phone before Nancy herself fully understands it, nudging, teasing, and encouraging her with the ease of long familiarity.

Magically, she stands at a crossroads between cozy domestic witchery and serious power: her apothecary, her cauldron, and her talking microwave are whimsical, but she also sees through illusions instantly, reads Nancy’s aura, and understands the mechanics of familiars and pacts in a way Nancy does not yet. That combination of competence and humor makes her a reassuring presence; she refuses to dramatize Nancy’s “weirdness” as a problem and instead treats it as a resource.

Cassie’s most important contribution to the story is re-framing Nancy’s love and magic as solutions rather than liabilities. When Nancy comes to her desperate to “fix” Jack’s shifting problem, Cassie does not respond by taking over or casting a complex spell.

Instead, she hands Nancy a stack of books and, with a knowing sort of mischief, tells her that Nancy’s own feelings are the most potent magic available. Her suggestion that Nancy literally cover Jack in her magic is half instruction, half push toward emotional honesty, because Cassie can see the “heart eyes” on both sides long before Nancy and Jack can admit them.

Rather than being jealous, threatened, or overprotective, Cassie roots for their relationship and treats Jack’s demon nature as just one more supernatural fact to manage, not an automatic danger. In doing so, she models a world where being magical and being loved are compatible, carving out space for Nancy’s eventual full acceptance of herself.

Popcorn

Popcorn begins as Nancy’s anxious, clingy little dog, a symbol of her craving for comfort and the small, manageable sort of responsibility she feels capable of handling. He is comic relief in early scenes, with his tendency to attach himself to her, complicate her plans, and end up in the middle of chaotic moments like the visit to Jack’s cabin.

Once Nancy’s magic fully wakes up, he reveals himself as a familiar with a grand, theatrical voice and surprisingly sharp insight. His transformation from silent pet to opinionated, talkative presence mirrors Nancy’s own shift from mutely enduring to articulating what she wants and what she believes.

As a familiar, Popcorn represents Nancy’s intuition and fierce loyalty externalized. He is not conventionally brave in a heroic sense, but he is absolutely ferocious about her safety, barking at hellhounds, protesting Jack “defiling” her after they sleep together, and refusing to accept plans that leave her unprotected.

At the same time, he is capable of tenderness and grief, comforting her when Jack is dragged back to Hell and helping her think about how to reach Jack again. His idea that Hell “isn’t that far” is both absurd and unexpectedly wise, nudging Nancy toward action instead of despair.

By working with Jack’s magical truck, he becomes part of the rescue team, embodying the story’s theme that love and loyalty, even in small packages, have real power against overwhelming darkness. Popcorn is one of the ways the book insists that the magical world is not only terrifying but also silly, affectionate, and full of surprising allies.

Seth

Seth, Cassie’s partner, is a werewolf whose supernatural side is deliberately understated, mirroring Jack’s situation but with a very different emotional tone. Where Jack is all jagged edges and self-hatred, Seth presents as calm, steady, and quietly protective, a man who has already made peace with his dual nature.

His relationship with Cassie provides an example of a functional, trusting human–supernatural partnership, complete with domestic chaos and shared jokes, rather than grand tragedy or fear. When Jack nervously copies Seth’s gestures at the dinner table, trying to act like a “normal” guest, Seth becomes an unconscious role model for a different kind of masculinity, one rooted in gentleness and reciprocity instead of dominance.

In the broader emotional landscape of Dealing with a Desperate Demon, Seth’s presence lowers the stakes around monstrosity. He shows that being something other than human can coexist with romance, community and light-hearted interactions.

That context is crucial for Jack, who has learned to see his demon side as exclusively tied to cruelty and punishment. Watching Cassie treat Seth’s wolf nature as normal and even endearing helps Nancy and Jack imagine a future where Jack’s demon form does not have to be hidden or feared.

Seth’s understated kindness and his willingness to welcome Jack, even once he realizes Jack is far more dangerous than an ordinary werewolf, reinforce the theme that chosen family can include literal monsters, as long as trust and care are present.

Nancy’s Parents

Nancy’s father is one of the most quietly terrifying figures in the story, because his power comes not from magic but from authority, fear, and the ability to define reality for his child. When Nancy is young and her writing produces tangible magic, he responds by breaking her pen and sending her to a mental hospital instead of protecting and guiding her.

This choice tells Nancy, in the most brutal way possible, that her perceptions are wrong and shameful, and that even the person who should be her fiercest defender is willing to hurt her in order to impose normality. He stands in for every social structure that pathologizes sensitivity and imagination, especially in girls, and treats their experiences as hysterical or dangerous rather than as signals that something real is happening.

The emotional damage her father inflicts ripples through the entire story. Nancy’s constant second-guessing of her own mind, her reluctance to talk about her childhood memories, and her panic in the dark all originate in that early rejection.

Even when supernatural events escalate in Hollow Brook, her first instinct is to assume she is “crazy” rather than to trust what she sees. Jack’s outrage on her behalf—his insistence that a good father believes his daughter and protects her—is a key step in untangling this damage.

By naming her father’s behavior as wrong, he helps Nancy step out of the mental cage her father built. Interestingly, the demonic contract Jack suffers under echoes her father’s control: a punishing, conditional structure that says love must be earned by meeting impossible terms.

Breaking that contract is symbolically linked to breaking her father’s hold on her sense of self. Though her father is largely offstage in the present-day sections of the book, his shadow is long, and much of Nancy’s story is about reclaiming the narrative he stole from her when he snapped her pen.

Nancy’s mother appears less directly than her father, but she is part of the strict, fearful parental unit that responds to Nancy’s magic with repression instead of care. Even if she is not the one physically breaking pens or signing commitment papers, her complicity matters.

Her silence and agreement tell Nancy that there is no safe adult in her family, no one she can turn to who will believe her about the monsters in the dark or the voices in the walls. This absence of maternal protection makes Nancy’s later found family—Cassie, Popcorn, Jack, and even the enchanted furniture in Jack’s remade cabin—all the more significant.

Each new relationship that offers comfort, belief, or shelter stands in contrast to a childhood where those things were withheld.

As a symbolic figure, Nancy’s mother represents the ways love can be warped by fear. She may believe she is doing what is best by supporting “treatment” and siding with Nancy’s father, but the result is that she abandons her daughter emotionally at the moment Nancy most needs a champion.

The book does not focus on redemption for Nancy’s parents; instead, it allows Nancy to find mothering energy in her friendships, in Cassie’s guidance, and in her own growing ability to care for herself and others. In that sense, Nancy’s mother is important less for her individual personality and more as a contrast point for the nurturing, intuitive women Nancy eventually aligns herself with.

Pod the Raccoon

Pod, Cassie’s raccoon familiar, adds a thread of vivid chaos to the story’s magical tapestry. He is mischievous, greedy, and utterly unconcerned with human dignity, happily stealing shoes and, later, riding Popcorn around the house like a tiny, furred despot.

His antics keep the scenes at Cassie’s house from becoming too heavy or didactic; whenever talk veers toward serious magical theory or the grim stakes of Jack’s pact, Pod’s presence reminds everyone that magic is also about unpredictability and play. In a world where demons wield hammers and Hell enforces contracts, Pod’s primary goals are snacks and fun, and that contrast is soothing.

At the same time, Pod serves a subtle narrative purpose. His existence as a clearly magical, obviously sentient creature helps normalize the supernatural for Nancy and for Jack.

If a raccoon can be a familiar, if a microwave can snark, then a demon can be a boyfriend and a witch can be a traumatized former patient who runs a bookstore. Pod’s chaotic energy encourages flexibility and improvisation, qualities Nancy needs when she later crashes Jack’s truck into Hell and navigates its shifting spaces.

In the network of relationships that make up Nancy’s new life—witch, demon, werewolf, dog familiar—Pod is the little agent of entropy that prevents the magical world from hardening into yet another set of strict rules.

Themes

The Transformative Power of Mutual Care and Emotional Safety

From the very first crash on the dark forest road, what reshapes both Nancy and Jack is not grand declarations but the steady repetition of “I’ve got you.” Jack pulls Nancy from the wreck, carries her, bandages her ankle, and later quite literally fights Hell for her, yet the story constantly links these big gestures to small, careful acts: asking before he touches her injury, kneeling to wrap her leg, letting her dictate whether they go to the hospital, listening when she says she cannot afford it. His size, his power, and eventually his demon nature never matter as much as his willingness to adjust himself to her comfort.

At the same time, Nancy quietly builds a refuge around him. In the restaurant that clearly was not built for someone his size, she reframes his clumsiness as the room’s fault, not his.

When he nervously hides his love of desserts, she orders every sweet on the menu and treats his joy as normal instead of shameful. Her bookstore becomes a place where his “enormous butt” and “meat hooks” are welcomed, where his notes on romance novels are taken seriously instead of laughed at.

Care is never one-sided. Nancy’s panic attacks, her fear of the dark, and the resurfacing of her childhood “hallucinations” could easily have been used to mark her as fragile.

Instead, Jack sits on the floor with her in the closet doorway, holds her, gives her a pen and notepad, and insists that the words she needs should be written as if they are true. When she finally writes “Let me be,” his respect for that act allows her to reclaim power over her fear.

Later, she returns that care by using her magic brush on his body in a way that is deliberately gentle, rewriting the infernal control over his form with tenderness rather than violence. Their relationship in Dealing with a Desperate Demon suggests that emotional safety is not abstract; it is built from asking permission, owning mistakes, and creating spaces where preferences, vulnerabilities, and strange histories are treated as precious rather than inconvenient.

In that environment, both of them learn that they are not burdens to be managed but partners who can steady each other.

Monstrosity, Shame, and the Right to Be Loved

Long before Nancy sees horns or living furniture, Jack is already marked as monstrous. The town knows him as the furious giant who passed out in the fountain; headlines reduce him to a spectacle.

He internalizes that framing so thoroughly that he assumes no “nice, soft girl” could ever accept the man behind the temper. When Nancy steps into his cabin, the contrast between reputation and reality is striking: fairy lights, kitten portraits, tea cozies, and VHS romances crowd the space of a man who has spent years trying to make himself gentle while believing he is inherently wrong.

His later confession that his sexual history has mostly consisted of anonymous, unpleasant encounters “by trash cans” shows how deeply he has accepted a role as someone only fit for degradation, never for dates, dinners, or devotion.

Nancy carries her own version of monstrosity. As a child, her writing magic produced impossible phenomena, and instead of wonder, she met fear and control.

Her father’s choice to break her “wand” pen and have her institutionalized taught her that her perceptions made her dangerous, that she was the problem to be fixed. Even as an adult, she calls her experiences “waking nightmares” and “delusions,” policing her own mind the way others once did.

In Dealing with a Desperate Demon, these two people meet at the point where self-disgust and longing collide. Jack calls himself an ogre; Nancy worries that any man who sees how “weird” she is will leave.

The revelation that Jack is literally a demon magnifies the metaphor. He works in Hell’s punishment department, wielding a huge hammer against people so vicious he will not even describe them.

The story does not excuse that violence, but it insists that his job, his body, and his origin do not erase his capacity for kindness, softness, and joy. Nancy’s response to his demon form is not horror but recognition; the physical manifestation of his “monstrous” self finally matches the shame he has always carried, and she can look at it without flinching.

By loving him as both man and demon, she asserts that monstrosity has been defined by other people’s fear, not by his actual behavior. Her own acceptance as a witch mirrors that arc: the magic that once had her locked away becomes the key to freeing them both.

The theme insists that everyone, no matter how they have been branded, has a right to be cherished fully, not only in sanitized, acceptable pieces.

Reclaiming Magic, Narrative, and Self-Definition

From the opening image of a teenage girl writing reality into being to the ending where “and they lived happily ever after” literally rewrites a demonic contract, Dealing with a Desperate Demon treats stories as a primary engine of identity. Nancy’s first great spell begins with “Once upon a time, there was a prince who wasn’t” and channels all her grief and desire into text.

Her father’s violent interruption, snapping the pen and severing her connection to magic, is not just parental cruelty; it is an attempt to seize control of the narrative of who she is. The years that follow are dominated by other people’s stories about her: doctors labeling her experiences as psychosis, parents describing her as broken, a hospital that tries to purge her imagination.

The result is a woman who, at the start of the present story, still calls her visions hallucinations and treats her earlier miracles like shameful fantasies.

When Jack hands her the company-branded pen and tells her to write what she needs “as if it’s real,” he hands back authorship of her life. The phrase “Let me be” is simple, but it marks a crucial shift from being written about to writing herself.

As she reawakens to her magic, she tests the limits of what words can do: trying to engineer a consequence-free break in the pact, crafting careful conditions, watching them melt or vanish when doubt or fear undercuts intention. The failure of those early attempts shows that power without self-belief remains partial.

Hell’s buzzing, clown-honking rejections dramatize how oppressive systems mock and resist attempts to rewrite their rules.

The turning point comes when Nancy understands that the most effective magic is not clever legal phrasing but a return to the unfinished story she began as a teenager. That story called a “prince who wasn’t” into the world; the pact is, in a sense, a hostile edit layered on top of her original text.

By finishing it with a classic fairy-tale ending, she asserts that her first intention has primacy over Hell’s amendments. The happy ending stops being a cliché and becomes a literal contract clause, backed by the full weight of her belief and love.

Narrative here is not escapism; it is a constitutional document for reality. The book suggests that healing requires taking your story back from those who distorted it, deciding whose version of you stands, and then committing to that version so fully that even infernal bureaucracy has to bend.

Trauma, Gaslighting, and the Long Road to Trust

The emotional core of Nancy’s journey lies in the damage done when adults label a child’s reality as dangerous. As a girl, she heard animals speak, saw magic respond to her words, and created wonder that frightened her parents.

Their response was not curiosity or protection but terror and containment: taking away her tools, calling in doctors, and eventually having her committed. The hospital does not treat her with dignity; it treats her as a problem to be solved, enforcing a version of “normal” that ignores the very real monsters circling her life.

The hazy memory of the institution burning, a rescuer lifting her to her feet, and her father’s ongoing insistence that she was simply ill combine to leave Nancy unsure whether to trust her own recollections. This is classic gaslighting at a supernatural scale: both her perception of the world and her sense of her own mind are cast into doubt.

By the time Jack walks into her bookstore, Nancy has built habits of self-protection around that doubt. She dismisses her own fear in the dark, jokes through panic, calls her visions “delusions” before anyone else can.

She assumes that if she shows too much of her inner world, she will be punished or abandoned. Trust, for her, is not about romantic chemistry but about whether someone believes what she says about her own experience.

Jack’s fiercest anger, tellingly, ignites not when people mock him, but when he hears how others have dismissed her. He condemns her father’s actions, insisting that a good parent believes their daughter, and treats the Return to Oz book as a meaningful text rather than childish obsession.

When she describes the “waking nightmares,” he does not correct her; he asks what she needs and provides it, pressing the pen and notepad into her hand and validating her ritual instead of trying to stamp it out.

Trust grows slowly out of this consistent pattern. She trusts him with the story of the hospital fire; he trusts her with centuries of horror from Hell.

He reveals that human form quiets some of those memories, a confession of vulnerability that undercuts his own persona of the unshakeable enforcer. Each time one of them shares a painful truth and the other responds with care instead of judgment, another layer of old conditioning is peeled back.

By the time Nancy drives a truck into Hell itself, the reader has seen how far she has come from the girl who second-guessed every perception. She now trusts her own magic enough to confront devils and her own heart enough to insist that she loves Jack, even in the face of damnation.

The book traces trauma not as a single wound but as a pattern of disbelief that must be replaced, piece by piece, with relationships that honor what the survivor knows about themselves and their world.

Bodies, Desire, and the Politics of Worthiness

Physicality is constantly on display in Dealing with a Desperate Demon, not as mere fan service but as a site where shame and liberation clash. Jack is enormous, hairy, scarred by his work, and visibly outside conventional “tidy boyfriend” norms.

Town gossip treats his size as menacing; even he talks about his “meat hooks” and “enormous butt” as hazards rather than assets. His father demanded a “tough” persona, and strangers judge his food choices, so he internalizes the idea that his body must perform a narrow brand of masculinity: stoic, savory-food-eating, rough.

Pleasure and softness seem off-limits; desserts and cuddling read as weaknesses that someone like him has not earned.

Nancy’s gaze overturns that logic. When he strips off his Henley and panics about looking like a wild beast, she reaches for Her Viking Beloved and uses it as evidence that many women fantasize about men who look exactly like him.

The annotated copy shows he has been treating these texts as instruction manuals, dissecting sex scenes like equations he hopes to solve. As she guides him through their first hug, linking his memory of cradling her injured ankle to how he might hold her body, the story ties his physical power directly to gentleness.

His large hands are not threats but tools for care; his weight, when he leans into the embrace, becomes grounding rather than suffocating.

Nancy’s body is also framed with warmth and desire. She is not a tiny waif; she has curves that she has sometimes felt self-conscious about, yet Jack sees them as “awesome… on a woman.” The sex between them is explicit but consistently respectful, anchored in consent, communication, and the acknowledgment of her pleasure as central.

Her first orgasm with him is treated as an important milestone; he is shaken by the knowledge that he could give her more than she has ever been able to give herself. The narrative makes room for her sexual agency without shaming her history or suggesting that trauma invalidates her desire.

When she bluntly asks him to “just fuck me,” the moment refuses the idea that a “nice girl” must be passive.

The repeated focus on what they eat, how they sleep, how they touch, and how they see one another undercuts cultural messages that only certain bodies deserve romance or happiness. A big man drinking milk like shots, a woman in a bobble hat demanding pleasure, a demon learning that his monstrous form is still worthy of tenderness: all of these images critique narrow beauty and gender standards.

The theme argues that worthiness is not measured by conformity to those standards but by how people treat each other, especially when they are most exposed.

Contracts, Choice, and Defying Hellish Systems

Looped through the love story is a legalistic nightmare: Hell as a bureaucracy that binds souls with dense, rigged agreements. Jack’s existence in the human world rests on a pact that demands a woman say “I love you” to him by a specific deadline, under conditions that were never fully explained to Nancy.

The contract’s terms are opaque, its enforcement extreme, and its penalties collective; not only Jack but anyone who helps him may suffer if he fails. This structure echoes abusive systems on Earth: institutions or families that impose rules without transparency and punish disobedience with disproportionate force.

Nancy’s attempts to negotiate with the pact illustrate both the ingenuity and the limits of working within an unjust system. She tries phrase after phrase to protect Jack and everyone around them: “When the pact is broken there will be no bad consequences,” “Once Jack is free, keep everyone safe from harm.” Each time, the magic rejects the language.

The clown-honk feedback from the contract is darkly comic, yet it underscores how those in power dismiss human attempts to soften harsh rules as foolish or naïve. Jack’s explanation that magic needs aligned intention, belief, and emotion adds another layer: people who have been taught not to trust themselves struggle to assert their will clearly enough to override oppressive structures.

Even so, choice refuses to disappear. Both protagonists try to sacrifice themselves to spare the other.

Jack contemplates breaking the pact outright, accepting his return to Hell if it means fewer hellhounds stalking Nancy. Nancy drives into Hell to retrieve him rather than live with safety bought at the price of his torment.

The crucial line she finally writes, “May he be acted upon by no law but the one I first set,” reframes the entire situation. Instead of wrangling with Hell’s add-ons, she asserts the primacy of her original calling spell, stripping away the devil’s edits.

This is an act of civil disobedience in magical form: she refuses the legitimacy of unjust amendments and insists that the foundational intention governs.

The story does not claim that love magically abolishes all systems of harm, but it does show two people refusing to let those systems define their choices. In the end, the pact is not beaten by clever loopholes alone but by the combination of romantic courage, narrative authority, and a clear refusal to accept that Hell’s laws are the final word.

The theme suggests that contracts, whether infernal or mundane, are not neutral; they encode power. Genuine freedom lies in recognizing when those contracts are unjust and daring to rewrite or reject them, even when the cost is terrifying.

Friendship, Found Family, and Community

While the romance between Nancy and Jack anchors the plot, their survival and growth depend heavily on the people and creatures orbiting them. Hollow Brook might be saccharine on the surface, but beneath the cutesy decor and Halloween displays lies a web of relationships that eventually provide the acceptance Nancy never received from her biological family.

Cassie, with her apothecary, sharp insight, and chaotic raccoon familiar, steps into the role of mentor and sister-in-magic without hesitation. She sees Nancy’s silver aura, reads her desperate desire to help “someone you like,” and responds not with suspicion but with practical support: books on witchcraft, blunt advice about using her own power, and a wicked sense of humor about the “heart eyes” Nancy and Jack share.

Seth, the werewolf hiding behind normality, mirrors Jack’s struggle with monstrous identity, yet he moves through life with far more ease, showing what acceptance might look like for Jack in the future. Popcorn, the little dog who suddenly starts speaking in a fussy actor’s voice, is both comic relief and emotional anchor; as Nancy’s familiar, he comforts her in grief and pushes her toward action, insisting that Hell “isn’t that far” when she is ready to give up.

Even Pod the raccoon, riding Popcorn around the house, contributes to a sense of a household where oddness is ordinary and magic is domestic rather than terrifying.

These relationships stand in stark contrast to Nancy’s parents and Jack’s father, whose fear and rigid expectations caused so much harm. Where her family dismissed her perceptions, Cassie believes her immediately.

Where Jack’s father demanded toughness and suppressed softness, Seth and the others accept Jack’s anxious politeness and his earnest attempts at good manners. The double date at Cassie’s house, with Jack copying table manners and trying to be a polite human guest while secretly guarding the dog, underlines how much he wants to belong.

Cassie’s simple assertion that fixing his shifting problem is “easy” once Nancy uses her own magic reframes his curse as something the community can help hold, not a solitary burden.

By the epilogue, when Nancy and Jack attend a New Year’s party as a couple surrounded by both human and supernatural friends, the book has replaced the isolating environments of their youth with a genuinely inclusive circle. Found family here is not a sentimental backdrop; it is a protective structure that allows a witch and a demon to stop hiding the most important parts of themselves.

The theme emphasizes that love between two people is strengthened, not diminished, when it is rooted in a larger community that understands, supports, and occasionally teases them into greater honesty.

Romance Media, Genre Awareness, and Learning How to Human

One of the most playful yet thoughtful threads in Dealing with a Desperate Demon is its meta-conversation about romance stories themselves. Jack arrives at Nancy’s shop clutching How to Be the Ideal Human Boyfriend and later devours six long romance novels in a single night, filling a notepad with questions.

For him, these books are not idle entertainment; they are textbooks on human behavior. He interrogates tropes like tall, brooding heroes, “safe assholes,” and asking a father for his daughter’s hand, testing them against his own circumstances: what if the father is abusive, what if the man is genuinely frightening, what if violence is not symbolic but his actual job?

His confusion exposes the gap between fantasy conventions and real-world ethics.

Nancy, as both romance reader and bookseller, becomes an interpreter between genre and reality. She explains that “safe assholes” are appealing because the stories guarantee their transformation and because the heroine’s safety is never truly in doubt.

She clarifies that in real life, scary behavior is not sexy if you do not trust the person behind it, and that parental permission is irrelevant when the parent is harmful. Their conversations about enemies-to-lovers, about men who act angry because they like the woman, mirror their own dynamic and heighten the tension as both recognize themselves in these patterns.

The book uses this self-awareness to critique lazy uses of tropes while still celebrating the emotional satisfaction they can offer.

Jack’s reliance on movies and novels to learn “how to human” underlines both the power and the limitations of media. He mimics table manners from films, names foods from John Candy movies when he panics, and models his understanding of dates and proposals on fictional scenes.

Without Nancy, this could have left him locked in a performative version of humanity that never quite fits. With her, the stories become a starting point rather than a script.

She encourages him to focus on genuine curiosity about his partner instead of pre-approved topics, and to let his actual preferences show, whether that means ordering dessert or admitting he does not know how to hug.

The final twist, that her unfinished fairy tale is the foundational spell behind the pact, closes the loop between fiction and life. The “prince who wasn’t” is both a romance archetype and a specific demon trying to be worthy of love.

By completing the story with a happy ending, Nancy uses the very genre she loves to dismantle Hell’s claim on them. Romance books are no longer just manuals for Jack or comfort reads for Nancy; they are blueprints for building a world where the values those stories promise—consent, transformation, safety, devotion—are taken seriously.

The theme suggests that media can mislead if copied uncritically, but that when filtered through empathy and honest conversation, it can help people who feel alien learn new ways of being together.