The Art of Spending Money Summary and Analysis

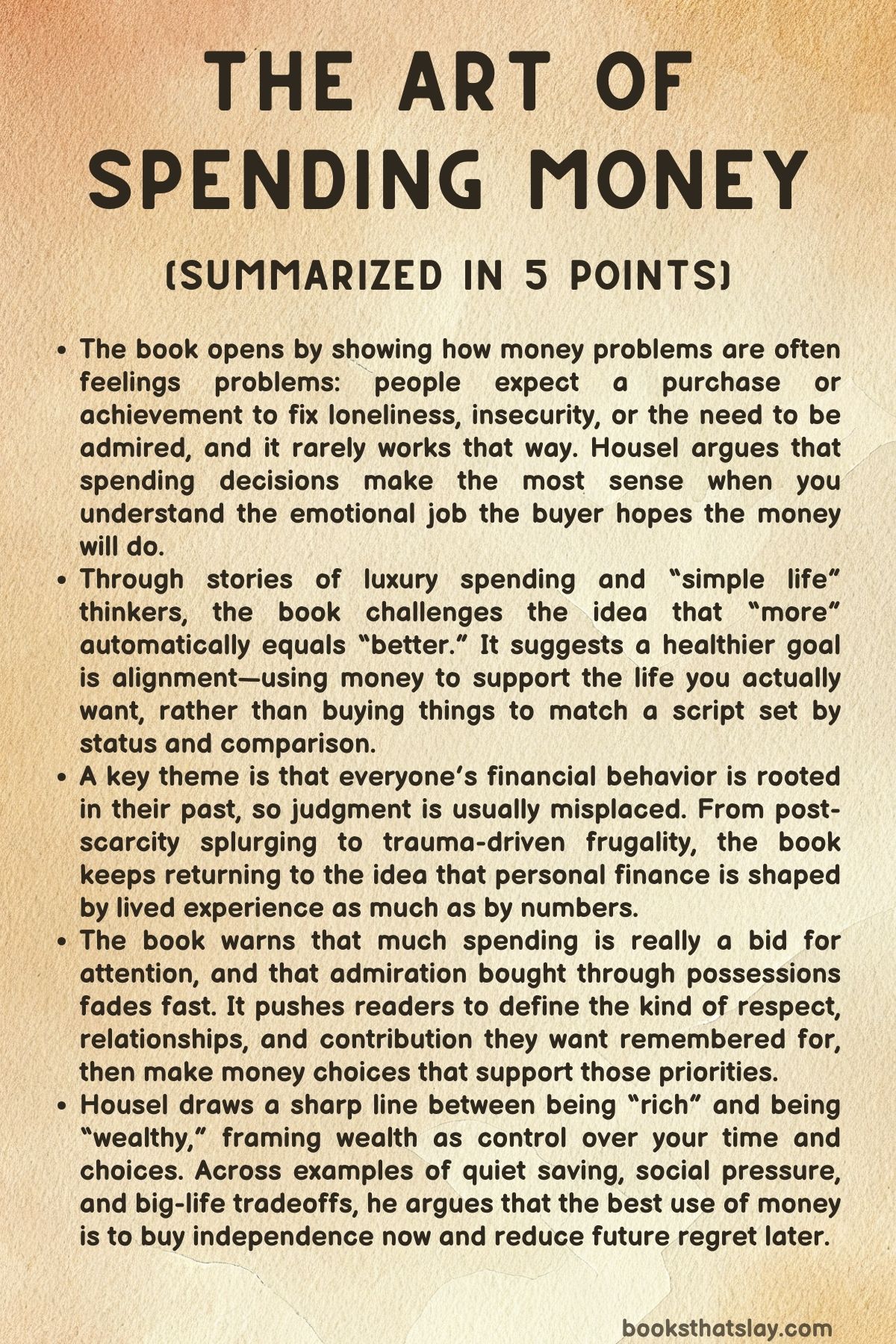

The Art of Spending Money by Morgan Housel is a book that augments with an argument that spending decisions are rarely about numbers and almost always about emotion. Through real stories, history, and behavioral science, Housel shows how people use money to chase approval, cope with fear, repair old wounds, or buy a sense of control.

He challenges the idea that wealth is mainly about luxury and says the best use of money is to create independence, protect your time, and support the people and values you care about. The book’s focus is not budgeting tricks, but learning what you actually want.

Summary

The Art of Spending Money opens with a case from Dr. Dan Goodman: a woman gets successful LASIK surgery, yet feels crushed afterward. The procedure fixed her vision, but it did not deliver what she secretly expected—being admired, desired, and finally secure in herself.

The episode sets up the book’s main claim: money problems are often life problems wearing a financial costume. People can earn or buy what they think they want and still feel empty, because the real need is usually belonging, peace, confidence, or meaning.

Money can support happiness, but not in the direct, mechanical way people assume.

The author then shares his own lesson from working as a valet at a luxury hotel. He watches wealthy guests treat extravagant purchases as a script they are expected to follow.

One man boasts about paying $21,000 for a chair, not because it improved his life, but because it signaled that he belonged in a certain world. The author starts noticing a pattern: many people chase wealth as a default goal, following social cues more than personal values.

They buy what looks impressive and hope it will translate into respect, identity, or satisfaction. But the more your spending is aimed at proving something, the more it can trap you in a cycle of needing to keep proving it.

From there, the book argues for a “simple life,” not as poverty or minimalism-as-performance, but as a deliberate choice to keep money in its proper place. Drawing on William Dawson’s writing about simplicity and Benjamin Franklin’s warning that people often “buy pleasure” by selling themselves into a kind of slavery, the author describes how wealth can create captivity: anxiety over keeping up, fear of losing status, and constant comparison.

A simple life, as he frames it, is one where you decide what matters and then use money to support that decision, rather than letting the chase for “more” decide for you.

The book then expands its lens: financial behavior is best understood through personal history. The author repeats a line that becomes a rule of interpretation—every behavior makes sense with enough information.

A social worker explains that children from chaotic homes may act out because it once kept them safe. In the same way, adults’ spending habits often come from old experiences.

The book points to the Roaring ’20s as an emotional response to deprivation and trauma from war: people spent hard because they wanted to feel alive again, not because it was prudent. In family life, a parent who grew up with scarcity might push a child toward the most expensive college as a symbolic reversal of their own past.

On the other side, someone who has lived through financial instability may become intensely frugal, not out of rational planning alone, but as a defense against the fear of returning to that pain.

The author uses psychology research to explain why people can look at the same purchase and see opposite meanings. Emotions, he argues, are shaped by culture and experience, so what one person sees as safety another sees as waste.

This is why judging other people’s spending is often misguided: you usually don’t know the story beneath the receipt. The book also describes how poverty compresses time.

When survival is the priority, long-term planning becomes harder, not because of laziness, but because immediate needs consume attention. Meanwhile, some high earners overspend to compensate for jobs they hate, trying to justify the sacrifice with visible rewards.

People who enjoy their work may save more easily because they do not need spending to soothe them. The key takeaway is that personal finance is deeply personal, and the right plan depends on the life behind it.

A major theme then comes into focus: many people do not want money as much as they want attention. The book argues that big homes and luxury cars are often purchased less for comfort than for visibility.

But admiration based on possessions is unstable, and it can disappear the moment someone else buys something bigger. The author suggests a “reverse obituary” exercise: write what you would want people to say about you after you are gone.

Most people, he notes, want to be remembered for love, generosity, loyalty, and impact—not for square footage or brand names. This gap exposes how often spending is aimed at the wrong target.

To help readers question endless ambition, the book shares a parable about a content fisherman and a businessman who urges him to work harder, expand, and retire early—only to discover that the fisherman already lives the life the businessman claims to be pursuing. The lesson is that happiness is largely the distance between what you have and what you want.

If your wants keep rising, no income will feel like enough. The author calls this “psychological wealth”: feeling rich because you want little, not because you own everything.

Desire, in this framing, is a quiet liability, and contentment is a form of freedom.

The book reinforces these ideas with stories about chasing validation versus choosing inner stability. In the Golden Globe Race, Donald Crowhurst enters under financial pressure and personal desperation, then fakes his progress to avoid humiliation.

The lie grows until it becomes unbearable, ending in tragedy. By contrast, Bernard Moitessier, positioned to win, rejects the fame awaiting him and sails on toward a quieter life, prioritizing peace over prizes.

The contrast highlights how dangerous it can be to build your identity on other people’s approval, and how powerful it can be to choose a life that fits your own values.

Another set of stories shows how appreciation depends on contrast. A man who regains sight after decades of blindness feels wonder at ordinary colors and textures, reminding readers that constant abundance can dull enjoyment.

The book uses this to argue that occasional luxuries often feel better than nonstop indulgence, and that restraint can preserve the ability to feel joy.

The author distinguishes “rich” from “wealthy.” Being rich is having money; being wealthy is having control over what money does to your time, choices, and identity. The Vanderbilt family’s decline becomes a cautionary tale of money feeding rivalry, addiction, and emptiness.

In contrast, Chuck Feeney exemplifies control by giving away almost everything and living simply, finding satisfaction in impact rather than display. The book also separates utility from status: a practical, comfortable purchase that genuinely improves your daily life can beat a prestige item bought mainly for applause.

Status is fragile because trends shift and the crowd moves on; utility lasts because it serves you.

As the book turns toward guidance, independence becomes the central goal. Savings are described as a purchase of future freedom: each saved dollar is a claim on your own time and options, while debt gives someone else a claim on your future.

Examples of athletes show the difference. One earns a fortune but loses control through extravagant spending; another earns less but saves enough to step away, change careers, and choose his next chapter.

Independence, the author argues, is what many people admire when they think they admire luxury.

The book warns about “social debt”—the unwanted consequences of visible spending: envy, obligations, pressure to keep up, and loss of privacy. A story about Frank Lucas illustrates how showing off can attract dangerous attention.

The solution offered is quiet compounding: building wealth slowly, privately, and consistently, guided by internal goals rather than public scoreboards. Finally, the author cautions against turning money into identity, whether as a compulsive saver or an endless striver.

He recommends experimenting with spending, then cutting ruthlessly what does not add real happiness, while keeping what reliably does.

In the end, The Art of Spending Money returns to limits: money can help you buy time with people you love, reduce stress, and choose work that fits your life. But it cannot substitute for love, health, or purpose.

The best measure of wealth is not what you own, but how small you can make the gap between what you have and what you want.

Key People

Dr. Dan Goodman

Dr. Dan Goodman serves as the opening moral compass of The Art of Spending Money, embodying the theme that fulfillment cannot be surgically or financially engineered. His patient’s story—of achieving perfect vision through LASIK yet failing to find happiness—reveals his understanding of the emotional void that material success often fails to fill.

Goodman represents reason and empathy in a world chasing superficial improvement. He is less a recurring character and more a philosophical anchor, illustrating how the pursuit of money or perfection without introspection leads to disillusionment.

Through him, the book immediately establishes that emotional well-being and meaning cannot be purchased, setting the tone for the broader argument that wealth’s true worth lies in freedom and peace of mind.

The Author (Narrator)

The author, Morgan Housel, stands as both storyteller and analyst in The Art of Spending Money, blending personal anecdotes with behavioral insights. His reflections—from his days as a valet observing the performative spending of the wealthy to his philosophical meditations on contentment—reveal a character deeply curious about human nature.

He oscillates between youthful awe of luxury and mature skepticism toward excess, embodying the evolution from financial naïveté to wisdom. Housel’s humility, observational clarity, and moral steadiness make him both participant and guide.

His tone suggests a man who has wrestled with envy, learned restraint, and now preaches balance: money should be a servant, never a master. His character evolves into the voice of quiet wealth—someone who values time, autonomy, and psychological peace over display.

William Dawson

William Dawson, introduced through his work The Quest of the Simple Life, symbolizes the liberating philosophy of voluntary simplicity. He is a reflective counterpoint to material ambition, showing how surrendering to wealth’s pressures enslaves the soul.

Dawson’s story exemplifies the serenity that comes from renouncing social competition and reclaiming time from material pursuits. He becomes an emblem of anti-consumerist wisdom—his “simple life” not an ascetic rejection of money, but a deliberate choice to live by values rather than comparisons.

Dawson’s presence in the narrative reinforces the book’s moral architecture: happiness arises not from accumulation but from conscious moderation.

Tiffany Aliche

Tiffany Aliche, referred to as a financial teacher scarred by “post-traumatic broke syndrome,” personifies the psychological imprint of scarcity. Her character exposes the invisible scars of financial trauma—how growing up with instability can make one fear spending even when secure.

Aliche embodies the defensive spender, whose frugality becomes both armor and prison. Through her, the book illustrates that every financial habit has emotional roots.

Her story adds empathy and realism, proving that even prudence can become self-destructive when guided by fear rather than peace.

Bernard Moitessier

Bernard Moitessier emerges as the novel’s philosophical hero, the embodiment of contentment and internal freedom. At the peak of potential glory in the Golden Globe Race, he rejects fame and fortune to “save his soul.” His decision to sail toward Tahiti rather than to victory crystallizes the book’s ethos: true wealth is autonomy—the ability to say no to status, noise, and expectation.

Moitessier’s serenity contrasts sharply with the desperation of Donald Crowhurst, revealing how inner direction defines happiness more than achievement. His quiet rebellion against materialism transforms him from sailor to sage, representing the book’s highest ideal of spiritual wealth.

Donald Crowhurst

Donald Crowhurst stands as a tragic mirror to Moitessier. His deception during the Golden Globe Race illustrates the spiritual bankruptcy of living for appearances.

Burdened by debt, societal pressure, and fear of humiliation, Crowhurst embodies the dangers of conflating worth with recognition. His mental unraveling and ultimate disappearance serve as the most haunting cautionary tale in The Art of Spending Money—a man undone not by failure, but by the unbearable weight of public judgment.

Crowhurst’s downfall underscores the book’s core warning: external validation is a debt with no end, and status-seeking can destroy both integrity and peace.

Michael May

Michael May, who regains his sight after decades of blindness, represents the psychology of gratitude and contrast. His rediscovery of ordinary sights—colors, faces, carpets—illuminates how happiness depends on perception rather than possessions.

May’s childlike wonder becomes a metaphor for mindful living; his joy shows that appreciation, not abundance, creates fulfillment. In a book about money, his character reminds readers that the richest experiences often emerge from re-seeing the familiar.

He teaches that the emotional return on wealth is proportional not to scale but to contrast—the ability to feel renewed appreciation.

Chuck Feeney

Chuck Feeney, the billionaire who gave away nearly all his fortune, personifies enlightened generosity. Unlike the Vanderbilts, who were consumed by their inheritance, Feeney transforms his wealth into liberation.

His modest living and quiet philanthropy redefine success as control over desire rather than accumulation. He embodies the concept of “quiet compounding,” investing emotional and social capital rather than material prestige.

Feeney’s character arc completes the moral spectrum of the book—from greed to giving, from ownership to freedom—illustrating that the ultimate return on money is moral peace.

Antoine Walker and John Urschel

Antoine Walker and John Urschel form a dual character study in financial philosophy. Walker, the exuberant NBA star who squandered millions, personifies impulsive wealth—living for others’ admiration and ending in dependence.

Urschel, his opposite, finds joy in discipline, using frugality to buy intellectual freedom and self-direction. Their contrast exemplifies the book’s thesis that independence, not income, defines true prosperity.

Walker’s bankruptcy symbolizes enslavement to image; Urschel’s contentment shows mastery over money’s temptations. Together, they dramatize the spectrum between reckless abundance and meaningful control.

Frank Lucas

Frank Lucas serves as a dark example of social debt and the peril of visibility. His downfall begins not with a business mistake but with a symbolic act—wearing an extravagant coat that announces his success.

Lucas’s story reveals how wealth can attract surveillance, envy, and ruin. He illustrates that attention is often the most expensive luxury and that discretion is the currency of safety.

His character reinforces one of the book’s final lessons: the more loudly wealth speaks, the less secure it becomes.

The Vanderbilt Family

The Vanderbilts represent inherited wealth without wisdom. Their internal decay—marked by rivalry, excess, and purposelessness—embodies the curse of unearned abundance.

Each generation drifts further from meaning, turning fortune into fragility. Their story operates as a generational parable, contrasting moral bankruptcy with financial inheritance.

Through them, The Art of Spending Money critiques the myth that money guarantees happiness, showing that without discipline and gratitude, great wealth only amplifies emptiness.

The Author’s Grandmother-in-Law

The author’s grandmother-in-law offers the gentlest portrait of contentment. Living modestly yet feeling wealthy, she demonstrates the emotional power of wanting little.

Her character distills the essence of psychological wealth—the ability to equate sufficiency with abundance. Unlike the book’s grander figures of fame or fortune, she embodies quiet wisdom, reminding readers that peace of mind, not possessions, is the final measure of wealth.

David Cassidy

David Cassidy’s dying words, “So much wasted time,” make him a posthumous philosopher of regret. His reflection condenses a lifetime of misplaced priorities into a single truth: money and fame cannot redeem neglected moments.

Cassidy’s voice haunts the reader as a warning to balance ambition with presence, and prudence with living. His inclusion closes the moral loop of the book, turning mortality into the ultimate financial metaphor—time, not money, is the true scarce resource.

Analysis of Themes

The Psychology of Money and Happiness

The Art of Spending Money by Morgan Housel underscores that money is far less about mathematics than it is about emotion, identity, and personal history. The book portrays financial behavior as a mirror of human psychology—our fears, desires, and insecurities expressed through spending.

Through the story of the woman disappointed by her LASIK surgery and the man boasting about an expensive chair, Housel illustrates that people often chase wealth or possessions hoping to fill emotional voids. Yet satisfaction does not emerge from numbers in a bank account but from alignment between money and meaning.

Emotional well-being, the book argues, is not bought with purchases but earned through self-awareness and independence. The author’s assertion that “personal finance is more personal than finance” reframes money as a reflection of inner life—how one’s upbringing, trauma, and expectations shape choices.

For instance, those who grew up poor may hoard or overspend as emotional compensation, just as those raised in abundance might undervalue what they have. This psychological framing transforms money from an external measure into an internal language of need and fear.

In this light, happiness is a function of perspective—of understanding why one wants what one wants. Emotional intelligence, rather than financial acumen, becomes the true driver of prosperity.

Housel ultimately argues that mastering money begins with mastering oneself: to spend consciously is to live consciously, recognizing that every financial decision is an act of self-expression.

Contentment and the Illusion of “More”

A recurring theme is the illusion that happiness lies just beyond the next purchase or milestone. Through stories like the fisherman and the businessman, Housel dismantles the myth of perpetual pursuit.

He presents contentment as the truest form of wealth—a psychological equilibrium where desires no longer outpace possessions. The book shows that when expectations expand faster than income, even great riches feel inadequate.

In contrast, those who find sufficiency in modest means experience a kind of inner abundance that wealth alone cannot deliver. The narrative of the author’s grandmother-in-law, who felt richer than billionaires because she wanted little, encapsulates this philosophy.

The book reveals that wanting less is a form of liberation; it releases people from the endless treadmill of comparison and status-seeking. The author’s critique of consumer culture—where “more” is an unquestioned virtue—exposes the trap of defining success through accumulation rather than satisfaction.

He contrasts superficial achievements with the quiet dignity of simplicity, reminding readers that material growth often fails to translate into emotional growth. True prosperity arises when the distance between what one has and what one wants is smallest, not largest.

Thus, The Art of Spending Money transforms the idea of wealth from a material condition into a state of mind—one shaped by gratitude, restraint, and clarity of values.

Independence as the Highest Return

The concept of independence—financial, emotional, and moral—emerges as the cornerstone of a good life. Housel redefines savings not as deferred consumption but as purchased freedom: each unspent dollar buys time, autonomy, and choice.

The contrast between Antoine Walker’s lavish collapse and John Urschel’s modest security highlights this idea vividly. Walker’s extravagance bought status but sold control, leaving him indebted and constrained, whereas Urschel’s restraint bought liberty—the power to pursue a meaningful life beyond wealth.

The book expands independence into a spectrum, showing how every act of financial prudence moves one closer to freedom from dependence, obligation, and social conformity. True wealth, Housel argues, is not how much you have but how little others can control your time or decisions.

This notion extends beyond money to include freedom from envy, from the need to impress, and from the anxiety of maintaining appearances. The text’s exploration of “hush money” and “social debt” illustrates how visibility can erode autonomy; the more people flaunt success, the more they become prisoners of public expectation.

In contrast, quiet compounding—building wealth steadily and privately—embodies lasting independence. The message is that money’s greatest power lies in its ability to let people live on their own terms, unburdened by fear, pretense, or dependence.

Status, Respect, and the Search for Validation

Housel’s exploration of human motivation exposes how deeply the desire for recognition shapes financial behavior. He suggests that many people do not truly seek money but the attention they believe it brings.

The section “May I Have Your Attention Please” unpacks this craving for admiration through examples of ostentatious spending, public boasting, and the social theater of luxury. Yet such validation proves transient and hollow, yielding fleeting bursts of pride followed by deeper dissatisfaction.

The author’s “reverse obituary” exercise—asking readers to imagine how they wish to be remembered—reveals that what most value is not status but substance: love, respect, and integrity. In comparing admiration earned through possessions with that earned through character, Housel draws a moral distinction between visibility and virtue.

He contends that pride rooted in wealth fades with fortune, while respect born of kindness or contribution endures. The analogy of “junk food” for vanity spending captures this perfectly: the pleasure is instant but nutritionally empty.

The book ultimately reframes admiration as something that cannot be bought or displayed; it must be lived. The pursuit of external validation is portrayed as a psychological trap, while genuine esteem arises from inner worth, humility, and authenticity.

The Meaning of Enough and the Trap of Comparison

Through parables and real-life contrasts, The Art of Spending Money defines “enough” not as a numerical limit but as a moral and emotional realization. The story of the content fisherman and the restless businessman functions as a metaphor for modern discontent.

The businessman’s endless striving represents the societal obsession with progress without purpose, while the fisherman embodies satisfaction rooted in the present. Housel shows that the inability to recognize sufficiency breeds perpetual anxiety, making people work harder for things they do not need to impress people they do not like.

The Vanderbilt family’s ruin and Chuck Feeney’s fulfillment illustrate opposite outcomes of this principle—one consumed by insatiable desire, the other liberated by giving. Desire, Housel writes, is a hidden form of debt: the more one wants, the poorer one feels.

Contentment thus becomes not complacency but mastery over craving. By teaching readers to measure success by tranquility rather than trophies, the author reframes ambition as something that should serve life, not consume it.

The theme emphasizes that peace of mind is not achieved through excess but through knowing when to stop, when to say “this is enough.”

Risk, Regret, and the Balance Between Today and Tomorrow

Another major thread in the book concerns time and the tension between living now and planning for later. Through stories ranging from David Cassidy’s final words to Jeff Bezos’s “regret minimization framework,” Housel presents life as a continual negotiation between present pleasure and future security.

He likens this to nature’s extremes—creatures that live fast and die young versus those that survive centuries through patience—and argues that humans must find balance between the two. The goal is not reckless spontaneity nor rigid austerity but a life that one’s future self will thank, not curse.

Memories and independence, the text explains, yield the highest return on investment because they compound emotionally even as money compounds financially. The book also explores how overemphasis on either extreme leads to regret: those who hoard miss experiences, while those who overspend lose freedom.

By advocating moderation and foresight, Housel positions financial wisdom as moral wisdom—the art of using time and money in harmony rather than opposition. His message is clear: wealth’s greatest gift is not accumulation but the ability to live without remorse, to reach the end of life without echoing Cassidy’s lament, “So much wasted time.”

Humility, Luck, and the Ethics of Wealth

In its closing reflections, The Art of Spending Money turns philosophical, asserting that kindness is the natural extension of financial wisdom. The story of Kevin Costner and Michael Blake becomes a meditation on humility and gratitude—the reminder that luck, not just effort, underlies most success.

Housel argues that the luckier one is, the more responsibility one has to be generous and empathetic. Wealth should expand moral awareness, not inflate ego.

He warns against the arrogance that wealth can breed and champions humility as a safeguard against moral decay. This theme closes the loop on the book’s message: money is a magnifier, not a transformer—it amplifies existing values, fears, and virtues.

The final insight is that the highest return on money is not status or luxury but character and peace. True financial success, therefore, lies not in outperforming others but in outgrowing the need to.