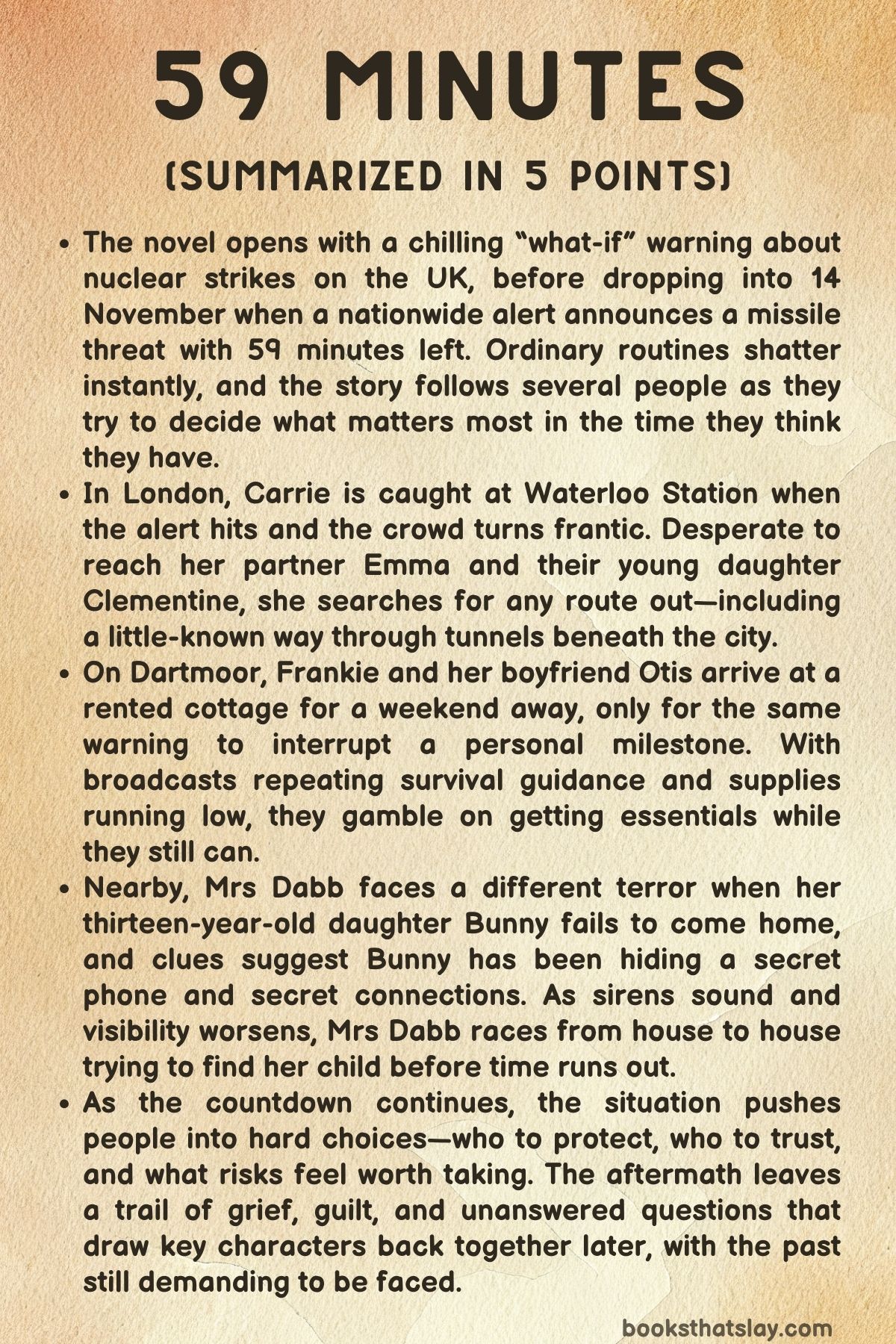

59 Minutes Summary, Characters and Themes

59 Minutes by Holly Seddon is a tense and emotionally charged exploration of human behaviour when confronted with the unimaginable. The story unfolds over a single terrifying hour in which the United Kingdom faces an apparent nuclear strike.

Through multiple perspectives—Carrie in London, Frankie in Dartmoor, and Mrs Dabb searching for her daughter—the novel examines fear, survival instincts, and the fragile connections that hold people together in crisis. As chaos spreads and time ticks down, Seddon portrays how ordinary lives unravel and intersect under extraordinary pressure, revealing hidden pasts, moral choices, and the lasting scars left when catastrophe almost strikes.

Summary

The novel opens with a stark warning describing the catastrophic effects of a nuclear attack on British soil. On 14 November, the unthinkable happens: a nuclear alert flashes across southern England.

Phones emit a deafening emergency tone, and screens everywhere display the same chilling message—there are 59 minutes until impact.

In London, Carrie, an advertising executive, is at Waterloo Station when the alert triggers. The festive buzz of commuters and marketgoers instantly turns to chaos.

Strangers cry, argue, and rush toward the Underground, desperate for safety. Carrie’s instinct is to reach her partner Emma and their three-year-old daughter Clementine in Kennington.

But the exits are blocked, and the police have sealed the station to prevent a deadly crush. Remembering an old commercial shoot, Carrie searches for a forgotten tunnel network beneath the station, determined to find another way out and get home.

Meanwhile, in a remote Dartmoor cottage, Frankie and her boyfriend Otis arrive for a quiet weekend away. Moments after Frankie reveals her pregnancy, their phones issue the same terrifying alert.

The couple scramble to understand what’s happening as government broadcasts urge citizens to take shelter, stock water, and avoid using the phones. Frankie reacts with urgency—filling bathtubs and containers with water—while Otis searches for supplies.

They realize they have no real food, no stable shelter, and little time. Despite orders to stay indoors, they set out in the fog to reach the nearest village, hoping to find essentials before the strike.

Elsewhere on Dartmoor, Mrs Dabb waits for her teenage daughter Bunny to return from school. The bus passes without stopping, and no one seems to know where Bunny is.

Mrs Dabb soon discovers her daughter forged a note to leave school early and that she may have a secret phone. As sirens echo through the moor and an emergency broadcast confirms the nuclear threat, Mrs Dabb’s anxiety spirals into desperation.

She drives through worsening fog to her mother Mary’s cottage, hoping for help, but finds only confusion and fear. Bunny’s disappearance becomes intertwined with the looming disaster, adding a personal urgency to the national panic.

Underground in London, Carrie forces her way into an abandoned maintenance corridor. She descends through old shafts and tunnels, navigating in darkness with her phone’s dim light.

Her only thought is to reach home. She is soon joined by Grace, a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl who followed her out of Waterloo, mistaking Carrie’s determination for knowledge of where to go.

The two move cautiously through the tunnels, avoiding the live rail and trying to reach a station closer to Kennington. As they go deeper, the faint sounds of chaos from above remind them that time is running out.

When Carrie falls and breaks her phone, Grace helps her up, and they continue together through a network of disused chambers, guided only by emergency signage and instinct.

Back in Dartmoor, Frankie and Otis reach a small village choked with people queuing outside a grocery store. The atmosphere is tense but brittle, with residents trying to stay calm as rumours spread about likely strike zones.

Panic erupts when one man mentions Devonport’s naval base, making everyone fear they are close to a primary target. The queue collapses into chaos as people fight to grab food.

Otis pushes into the mob to secure supplies while Frankie hides in an alley, trying to stay out of danger. When she returns, she finds destruction and hears the first distant sounds of explosions or crashes.

She runs toward their car, terrified for Otis.

Mrs Dabb’s search leads her to the Curtiss family’s farm, a place filled with dark memories and hostility. She suspects her daughter is there because of past connections between Bunny’s father and the Curtiss family.

The farm appears abandoned, its buildings crumbling, but lights flicker in one house. When she demands Bunny’s return, an elderly woman denies knowing anything and forces Mrs Dabb to leave.

The encounter leaves her shaken, convinced Bunny has been taken or misled by someone dangerous.

In London, Carrie finally escapes the tunnels and runs through a city collapsing under panic. Streets are littered with abandoned vehicles and injured people.

Explosions and gunfire echo as citizens turn on one another. She races through Kennington, passing scenes of chaos—children trapped in schools, fires spreading, helicopters spiralling overhead.

Every conversation revolves around the same desperate question: how many minutes remain? Eighteen.

Ten. Eight.

She pushes herself onward, thinking only of Emma and Clementine.

On Dartmoor, Frankie reaches Otis’s crashed car. He is alive but severely injured and unconscious.

As she struggles to move him, she encounters a terrified teenage girl who insists she must escape “the Curtisses.” The girl flees, leaving Frankie to face the decision of staying with Otis or saving herself. Injured and barefoot, she staggers toward a nearby cottage, banging on the door for help.

Inside lives Janet Spencer, an older woman who pulls her in, locks the door, and refuses to let her go back out. She tends Frankie’s wounds and leads her to a well-stocked cellar.

Frankie realizes, too late, that Otis has been left to die.

At 5:57 p.m., just moments before the supposed impact, every phone in Britain blares a new message: the missile threat has been a false alarm. Relief floods the country, but the damage—emotional, physical, and moral—is already done.

Days later, the aftermath reveals the true toll. Carrie is in shock.

Emma is dead, killed during the chaos outside their home. The garden has become a makeshift graveyard, and volunteer crews collect bodies without ceremony.

Carrie learns from the police that her mother, Janet, was shot by an intruder she had tried to help—Ashley Curtiss. Meanwhile, Frankie sits beside Otis in hospital, waiting for him to recover.

The nation debates leniency for crimes committed during the “59 minutes,” as prisons overflow with those who acted violently or desperately in fear.

A year later, memorials are built across the country. Walls of names fill parks and squares.

Carrie visits the Wall of the Fallen in St James’s Park, where Emma’s name is inscribed. She meets Frankie there, who has since given birth to a baby named Thorne.

Their shared grief connects them, but their conversation takes a shocking turn. Frankie reveals that in her final moments, Janet told Ashley Curtiss that Carrie’s daughter, Bunny, was his child.

Carrie is horrified; Ashley is alive and awaiting trial, and now he knows the truth. She begs Frankie to stay silent.

Ten years pass. Carrie, now living on Dartmoor and going by Mrs Dabb, receives word that Ashley has escaped custody.

As sirens blare once again, she and Mary barricade their home. Upstairs, Bunny comes face to face with Ashley.

He holds a knife but claims he only wants to talk. He confesses anger and regret, insisting that knowing about his daughter might have changed him.

Before he can flee, police surround the cottage. Ashley surrenders peacefully, asking Carrie to forgive his mother for her part in the past.

In the final chapter, ten years and nine weeks after the alert, Carrie and Bunny prepare to leave Dartmoor for Brighton. They visit graves, say their goodbyes, and pack their lives into a new beginning.

Carrie, finally at peace, allows herself to forgive the past—the mistakes, the losses, and the moments of panic that defined those fateful 59 minutes.

Characters

Carrie

Carrie serves as one of the central figures in 59 Minutes, embodying both the chaos and resilience of ordinary people caught in an extraordinary catastrophe. At the outset, she appears as a successful advertising professional, a mother, and a partner, moving through the comfort of a familiar London routine.

However, when the nuclear alert strikes, she becomes a study in instinct and desperation, driven solely by the urge to reach her partner Emma and their young daughter Clementine. Her journey through the suffocating crowd at Waterloo Station and into the dark, abandoned tunnels beneath London symbolizes her descent into fear and survival mode.

As she navigates the darkness, Carrie’s transformation is profound—her rational, controlled life collapses into raw human determination. In the aftermath of the false alert, she becomes haunted by loss: Emma’s death and the trauma of those 59 minutes.

Over the years, she evolves into a figure of quiet endurance, burdened by grief yet defined by her protective love for her daughter. Her eventual ability to forgive—others and herself—shows a hard-earned grace, illustrating how tragedy reshapes but does not destroy the human spirit.

Frankie

Frankie’s arc in 59 Minutes is that of survival, guilt, and motherhood entwined. Initially introduced as a woman seeking intimacy and stability with her boyfriend Otis, her revelation of pregnancy sets the tone for impending transformation.

The false nuclear alert rips through this fragile moment, throwing her into a desperate struggle to protect not only herself but the life growing inside her. Frankie’s pragmatic, quick-thinking actions—filling the bath with water, scavenging supplies, confronting chaos in the village—contrast with her internal panic.

Her later encounter with Janet Spencer, the older woman who shelters her, marks a turning point: Frankie finds safety at the cost of leaving Otis to die, a guilt that shadows her long after the danger passes. When Janet is later killed by Ashley Curtiss, Frankie’s sense of responsibility intensifies.

Her maternal instincts, already heightened by trauma, become the center of her identity as she raises her child, Thorne, while carrying the weight of past decisions. Frankie’s eventual meeting with Carrie at the memorial wall forces her to confront the tangled moral and emotional fallout of those 59 minutes, revealing her as a deeply flawed yet deeply human survivor.

Mrs. Dabb (Emma Dabb’s Mother)

Mrs Dabb stands as one of the most emotionally complex and tragic figures in 59 Minutes, representing the intertwining of family history, maternal anxiety, and intergenerational trauma. Initially seen as a distraught mother searching for her missing daughter Bunny during the crisis, her frantic energy mirrors the breakdown of order across England.

Her fear and guilt over Bunny’s disappearance lead her to confront dark remnants of her past, particularly the connection to the Curtiss family—a lineage tied to violence and shame. As the story progresses, it becomes clear that Mrs Dabb’s grief and anger are rooted not just in the immediate terror of losing Bunny but in years of secrecy and pain.

Her confrontation with the Curtiss family underscores how cycles of violence and fear persist even in times of national catastrophe. In later years, Mrs Dabb becomes a pillar of stability for Carrie and Bunny, despite her own losses.

Her resilience, often expressed through small acts of domestic endurance, embodies the quiet strength of those who survive and rebuild in the aftermath of devastation.

Bunny (Clementine Dabb)

Bunny, originally Clementine, is both a symbol and a survivor in 59 Minutes. As a child, she is at the heart of Carrie’s desperate race against time—a living embodiment of innocence amid apocalyptic fear.

In the novel’s later years, her identity becomes layered with history and revelation. The revelation that Bunny is Ashley Curtiss’s biological daughter reconfigures the story’s emotional landscape, linking the lives of the major characters in an unsettling web of secrecy and truth.

Growing up in the shadow of trauma, Bunny becomes a bridge between the past and the future. Her survival represents both the fragility and endurance of human life.

By the novel’s conclusion, as she and Carrie prepare to start anew in Brighton, Bunny’s presence radiates hope and continuity. She is the child of chaos, yet her resilience suggests renewal—a reminder that life can emerge even from the deepest scars.

Otis

Otis, Frankie’s partner, embodies the fragile masculinity and confusion of crisis. When the nuclear alert strikes, his initial responses—panic, speed, denial—reflect a man desperate to regain control.

His reckless driving through Dartmoor’s fog mirrors his internal chaos, and his eventual accident, leaving him severely injured, strips him of agency. In the hospital scenes that follow, Otis becomes both a victim and a haunting reminder of the event’s cost.

Though he survives, his role afterward is muted; his physical and psychological wounds render him distant. Through Frankie’s eyes, Otis represents the futility of human effort against uncontrollable forces, and his fate becomes a quiet tragedy within the broader narrative.

Janet Spencer

Janet Spencer, Frankie’s mother and one of the story’s moral anchors, embodies compassion and courage under impossible circumstances. When she shelters the wounded and pregnant Frankie, she acts out of empathy and practicality, offering refuge and comfort even as the world teeters on collapse.

Her calm, resourceful nature contrasts with the surrounding panic, and her stocked cellar becomes a symbolic womb of safety. However, Janet’s death—shot by Ashley Curtiss after helping Frankie—transforms her into a martyr figure.

Her final act of selflessness links the story’s main characters in grief and guilt. Through both her actions and her memory, Janet represents moral clarity and human decency in a time of moral collapse.

Her influence extends far beyond her death, shaping both Frankie’s and Carrie’s paths toward acceptance and healing.

Ashley Curtiss

Ashley Curtiss stands as the embodiment of violence, trauma, and moral corruption in 59 Minutes. His presence threads through the novel like a shadow—first indirectly, through fear and family history, and later directly, through his violent acts.

A member of a family steeped in toxic nationalism and paranoia, Ashley’s choices are shaped by inherited anger and isolation. His murder of Janet Spencer reveals the depth of his instability, yet his later confession and remorse complicate his villainy.

When he surrenders at the end, acknowledging his crimes and seeking forgiveness, he becomes a tragic figure—a man destroyed by the very fear and secrecy that engulf the others. His final confrontation with Carrie and Bunny reveals not redemption but a broken desire for connection, making him both monstrous and pitiful.

Pepper

Pepper, Carrie’s landlord and friend, provides a grounded, humane counterpoint to the chaos surrounding the main events. Throughout 59 Minutes, he is portrayed as kind-hearted, loyal, and emotionally attuned, offering stability amid the disintegration of normal life.

In the immediate aftermath, Pepper’s quiet grief—locking himself away after Emma’s body is taken away—shows the personal toll of collective trauma. His later years as Carrie’s confidant and emotional support illustrate the novel’s recurring theme of found family.

Pepper’s eventual death marks the end of an era for Carrie, but his memory continues to offer her strength and warmth.

Themes

Fear, Survival, and Human Instinct

In 59 Minutes, Holly Seddon constructs an intense psychological landscape shaped by the immediacy of terror and the primal instinct to survive. The false nuclear alert serves as the ultimate catalyst for revealing what lies beneath the surface of everyday civility.

Within minutes, normal life disintegrates, and the façade of modern order collapses, replaced by chaos and desperation. Seddon examines how fear strips people to their most elemental selves—reducing them from professionals, parents, or partners to frightened beings governed by impulse.

The novel captures how self-preservation clashes with morality, as seen in Carrie’s frantic attempt to reach her family, risking everything and everyone in her path. Frankie’s panic-driven decision to leave shelter in search of food, despite the government’s warnings, further underlines this raw instinctual pull.

The public panic in Waterloo Station and the violent scenes across London mirror collective hysteria, transforming familiar urban spaces into battlegrounds of survival. What stands out is Seddon’s refusal to romanticize fear; instead, she portrays it as corrosive, capable of destroying empathy and order in equal measure.

Fear reshapes priorities, tests relationships, and dissolves rational thought. Yet it also fosters resilience—Carrie’s determination to reach her child, or Frankie’s desperate effort to save Otis, illustrate how survival instinct can coexist with love and loyalty.

Through these contrasting reactions, Seddon argues that the line between courage and terror is razor thin, and that under pressure, humanity oscillates between compassion and cruelty. Fear, in the novel, is both the destroyer of connection and the force that defines it.

The Fragility of Society and Systems

The book exposes the precariousness of the structures that people assume will protect them—government, law enforcement, technology, and even community. The 59-minute warning reveals how swiftly those frameworks collapse when confronted with the possibility of annihilation.

The initial chaos in London demonstrates the illusion of control: automated announcements, digital screens, and emergency services fail almost instantly, leaving citizens directionless. Seddon emphasizes how dependent modern existence is on systems that promise security but deliver confusion when most needed.

The emergency alert itself—an official message meant to save lives—becomes the instrument of terror, showing how trust in institutions can be weaponized by error. The disintegration of order is not limited to technology; social bonds erode just as quickly.

Neighbours turn suspicious, crowds turn violent, and communities dissolve into self-interest. The aftermath, with frozen bodies left in communal gardens and no authority present to manage them, underscores a haunting truth: society’s structure is not built on resilience but on routine.

Once that routine is interrupted, humanity faces a void. Seddon’s critique extends into the aftermath, where inquiries and memorials attempt to impose meaning on failure.

The government’s “Hail Mary” sentencing system and the public debates around blame reveal how fragile moral accountability becomes when systems are strained. By contrasting pre- and post-alert life, Seddon underscores that civilization rests not on laws or governance but on mutual trust—a trust easily fractured and almost impossible to rebuild.

Guilt, Grief, and the Weight of Survival

Survival in 59 Minutes comes with an unbearable emotional cost. The narrative does not end with the false alarm but expands into the prolonged aftermath of trauma, guilt, and moral reckoning.

Those who live through the alert are haunted by what they did—or failed to do—during the 59 minutes of perceived doom. Carrie’s inability to save Emma, Frankie’s decision to abandon Otis to seek help, and Mrs Dabb’s frantic search for Bunny become psychological wounds that never fully heal.

Seddon’s portrayal of grief is neither sentimental nor redemptive; it is raw, disorienting, and cyclical. The surviving characters drift through years of mourning, questioning whether their choices were justified or cowardly.

Guilt becomes their permanent companion, more enduring than the fear that once drove them. The deaths caused not by nuclear fire but by panic and violence emphasize how human actions, not weapons, created the tragedy.

Seddon also explores inherited grief—the children growing up in the aftermath carry echoes of their parents’ trauma. The repetition of names, such as Clementine asking to be called Bunny, symbolizes how loss reshapes identity across generations.

Guilt also becomes intertwined with forgiveness; Carrie’s eventual ability to forgive herself signals a fragile form of survival, one that depends on emotional endurance rather than physical safety. Through these portrayals, the novel suggests that survival is not an escape from death but a confrontation with memory, where living on requires constant negotiation with one’s own conscience.

The Complexity of Family and Parenthood

Family, in Seddon’s story, is both the anchor and the source of conflict. Every major action stems from a desire to protect, reconnect, or redeem familial bonds.

Carrie’s desperate race through London is driven entirely by maternal instinct, while Mrs Dabb’s frantic search for Bunny illustrates how parenthood transforms fear into relentless determination. The maternal figures in 59 Minutes are not idealized; they are flawed, impulsive, and capable of destructive choices, yet their love defines their existence.

The story also interrogates unconventional family structures—Carrie’s partnership with Emma, the surrogate parental roles of Pepper and Mary, and the fractured connections within the Curtiss clan reveal the many forms family can take in modern life. The intersection of family and secrecy gives rise to devastating consequences: Carrie’s hidden relationship with Ashley Curtiss, the concealed truth of Bunny’s parentage, and the years of silence that follow expose how love can coexist with deception.

Seddon’s treatment of parenthood goes beyond protection; it examines inheritance—how fear, guilt, and trauma pass from parent to child. The final sections, where Carrie and Bunny prepare to move on from Dartmoor, capture the enduring tension between holding on and letting go.

Parenthood is shown as an act of persistence: to nurture life in a world that once promised destruction. Through these intertwined relationships, Seddon portrays family not as sanctuary but as a test of endurance, where love must contend with history, secrecy, and the haunting weight of survival.

Redemption and the Search for Forgiveness

Forgiveness in 59 Minutes is not easily granted; it is a process of confronting the unbearable truth of one’s actions and those of others. Seddon positions forgiveness as the ultimate form of survival—the emotional equivalent of rebuilding after devastation.

Carrie’s journey, from denial and self-reproach to eventual acceptance, embodies this struggle. The revelation that Ashley Curtiss is Bunny’s father forces her to face not only her past choices but also the moral complexity of her silence.

Frankie’s guilt over Janet’s death mirrors this internal battle; both women are trapped by the consequences of decisions made under duress. The novel’s later chapters, particularly Ashley’s surrender and Carrie’s final reflection, show that redemption cannot erase pain but can transform it into understanding.

Seddon refuses to simplify forgiveness into absolution; rather, it becomes a fragile agreement between the living and the dead. Forgiving others is inseparable from forgiving oneself, and both acts demand honesty, courage, and empathy.

The closing image of Carrie choosing to forgive herself as she and Bunny begin anew in Brighton serves as a quiet culmination of this theme. After years of turmoil, she finds peace not through external justice but through inner reconciliation.

Forgiveness, in Seddon’s vision, is the only form of control humans retain after catastrophe—the act that allows them to reclaim their humanity from the ruins of fear, guilt, and grief.