Merry and Bright Summary, Characters and Themes

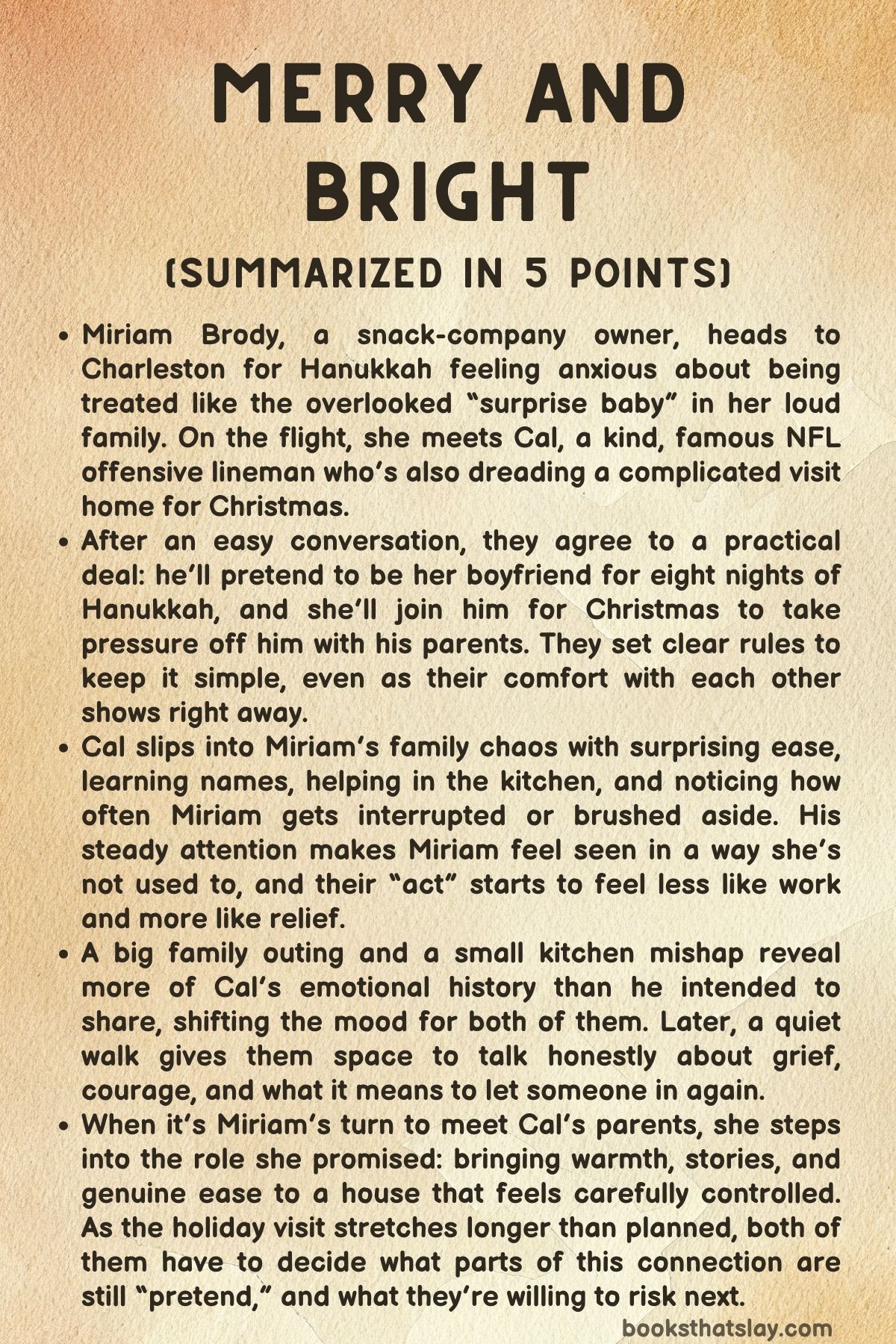

Merry and Bright by Ali Rosen is a holiday romance built around an unlikely deal between two strangers who meet on a flight to Charleston. Miriam Brody, a snack-company founder who often feels invisible in her own family, crosses paths with Cal Durand, a famous professional football player carrying more private grief than his public image suggests

They agree to pose as a couple through Hanukkah and Christmas to make family time easier. What starts as a practical arrangement turns into real comfort, real attraction, and a chance for both of them to rewrite what the season can mean. It’s the 2nd book in the Home Sweet Holidays series.

Summary

Miriam Brody heads to Charleston to spend Hanukkah with her family, bracing herself for eight long nights of noise, opinions, and being talked over. On the plane, the very large, very charming man beside her suggests they accept champagne, and the small choice opens the door to easy conversation.

Miriam admits she’s nervous about going home because her family can be overwhelming, and because she often feels like the extra person in the room, the “surprise baby” who never quite gets taken seriously. She makes jokes about competing for attention with her parents, her sisters, and even the family turtle, Shells.

The man introduces himself as Cal, and he listens in a way Miriam isn’t used to—like her stories matter.

When Miriam mentions she owns a snack company, Cal surprises her by recognizing her product, Nosh Sticks, and he even has some in his bag. Their talk turns into a lively back-and-forth about food, packaging, and favorite places to eat.

Cal then shares a piece of his own life: he’s a professional football player, an offensive lineman for the New York Giants. His fame isn’t the center of the conversation, though.

Miriam is more interested in why he’s traveling to Charleston for Christmas so early. Cal admits he tore his ACL last season, is on time off, and is finally going home after years of avoiding it.

He hints that his relationship with his family is complicated and that going home tends to turn him into a project instead of a person.

Half joking and half serious, Miriam suggests a solution: they could act as buffers for each other—someone to stand beside you so the family energy doesn’t hit you full force. Cal takes the idea and makes it specific.

He’ll come to Miriam’s Hanukkah celebrations as her boyfriend, and in return, she’ll attend Christmas Eve and Christmas Day with his family. They set rules to keep things simple: no sleeping over, but they’ll behave like a believable couple in public—hand-holding, closeness, and whatever small gestures make the story work.

By the time they land, Miriam agrees, surprised by how quickly this stranger already feels like a safe place to stand.

The moment Cal arrives at Miriam’s family home, the plan gets tested. Miriam’s mother is instantly thrilled, admiring Cal as if he’s a prize she can claim, while Miriam tries not to shrink into the wallpaper.

Soon the house fills with relatives—Miriam’s sisters Sarah and Nina, their spouses, and kids who move like a small stampede. Cal handles the chaos with calm competence.

He remembers names, asks thoughtful questions, and doesn’t act rattled when he’s recognized for football. Sarah’s husband Jeremy is especially excited to meet him, and the attention shifts toward sports talk the way it always shifts toward something that isn’t Miriam.

As the nights go on, Cal notices what Miriam has lived with for years. Her family interrupts her, talks over her, and treats her business like a cute hobby even though she works in food distribution and built something real.

They call her snacks “little,” and they speak about her as if she’s still a kid who needs managing. Cal quietly checks in with her and offers to step in, but Miriam admits that what helps most is simply having someone witness it and not brush it off.

In the middle of the noise, Cal becomes her steady point. He helps in the kitchen, peels potatoes, plays with the kids, and joins traditions without turning them into a performance.

He even bonds with Shells the turtle with genuine delight, which makes Miriam laugh when she least expects it.

Miriam’s attraction grows in small, accumulating moments: Cal slipping her a piece of cheese when she looks like she might crack, Cal catching her eye across a crowded kitchen, Cal making space for her in conversations by asking what she thinks and then actually waiting for the answer. The fake relationship begins to feel less like acting and more like being seen.

Still, their physical closeness stays restrained. When Miriam walks Cal out after the first night, he hugs her and gently tucks a curl behind her ear instead of kissing her, as if he wants to but won’t cross the line.

On the seventh night, the family goes to a public festival in Marion Square. Miriam is already tense from work problems, and when one of her sisters dismisses her concerns, Miriam snaps back with sharp humor.

Cal doesn’t scold her for it or try to smooth her edges. He’s amused, supportive, and stays right beside her as they wait in lines for food.

They watch a chaotic annual moment where firefighters toss little parachutes of chocolate gelt from a ladder truck and kids scramble to catch them. Miriam’s nephew Ethan refuses to join in, calling it stupid.

Cal crouches down to Ethan’s level and offers a different way to try: Cal will “block” for him like he does on the field. Ethan lights up.

Cal uses his size to protect a pocket of space in the crowd so Ethan can focus, and Ethan succeeds. The win becomes a bright spot for the whole family, and Cal earns Ethan’s trust in a way that feels earned, not forced.

The final night of Hanukkah shifts the mood. While cooking latkes, Miriam burns her finger badly enough to cause a commotion.

Cal rushes in and, based on something he saw online, tries putting her finger in his mouth to help, until the doctor in the family, Jenny, explains that cold water and ibuprofen are the way to go. In the scramble, Jeremy blurts out something Miriam didn’t know: Cal’s wife died in a skiing accident four years earlier, a fact that became public because of Cal’s fame.

The room goes still. Cal answers Ethan’s worried questions with calm reassurance and keeps the focus on Miriam’s safety, but the revelation changes everything for Miriam.

Outside, walking along the Battery in the humid December night, Cal apologizes for not telling her. He explains that talking to Miriam on the plane felt simple because she didn’t know his public story.

He describes his wife as his childhood neighbor and first love, someone fearless who believed in him long before anyone else cared about his football potential. After she died, Christmas became unbearable, and he stopped going home because every tradition was a reminder he couldn’t handle.

This year, therapy has helped him try again, but he’s still scared of what it will bring up. Miriam tells him that showing up at all is brave.

The closeness between them spikes, and Cal almost kisses her, then stops himself. He admits he feels like only half a person and thinks he isn’t good for her, even if being with her feels good.

Still, he returns with her to finish the last night, choosing presence over escape.

Two days later, it’s Miriam’s turn to step into Cal’s world. She arrives at his parents’ house on Christmas Eve in heavy rain.

Cal’s parents, Judy and Charles Durand, welcome her into a home that’s immaculate and intensely decorated, the kind of perfection that makes you sit up straighter. Cal is nervous, but he’s thoughtful—he gives Miriam socks because her shoes are soaked, a small kindness that feels like him.

At dinner, Miriam does the buffering she promised: she tells stories, asks questions, and brings warmth into the careful atmosphere. When flooding makes it unsafe to leave, Judy insists Miriam stay, and the no-sleepover rule collapses under weather and practicality.

Miriam and Cal end up sharing Cal’s childhood bed. The setup is awkward and intimate at once, and it forces them into honesty through silence—two people lying close, fully aware that the feelings are no longer pretend.

Cal suggests they hold on so no one falls off the small bed, and Miriam agrees. She sleeps wrapped against him, comforted in a way she didn’t realize she needed.

On Christmas morning, Miriam wakes alone and joins the family downstairs. Judy and Charles fuss over her, and Miriam feels genuinely included.

Cal gives her a second gift: a blue Hanukkah ornament shaped like a turtle shell with a menorah, something he found after visiting a synagogue gift shop and learning turtle facts from a talkative volunteer. The gift is specific, funny, and tender, proof that he pays attention to the details that make Miriam Miriam.

They spend the day opening presents, watching movies, cooking, and eating together, and the holiday becomes lighter for Cal than it’s been in years.

When it’s time for Miriam to leave, Cal thanks her for making Christmas feel good again. They hug, and Miriam kisses his cheek, assuming the arrangement has reached its end.

The next morning, the emptiness hits her hard. Miriam realizes she can’t accept Cal’s belief that he’s broken or only half present in life.

She decides to tell him that grief doesn’t cancel the possibility of new love and that he deserves more than survival.

Before she can go to him, Cal arrives at her door with a homemade charcuterie-and-cheese bouquet—ridiculous, thoughtful, and perfectly on theme for the way they bonded. He admits he was wrong to push her away.

He’s scared, but he doesn’t want to lose her, and being with her makes him feel like he can breathe. Miriam tells him he isn’t damaged goods and that love has expanded him, not reduced him, even if her metaphor comes out clumsy.

Cal laughs, lifts her up, and kisses her for real. Then he reveals he already made a dinner reservation in New York at a restaurant he’d mentioned before, choosing action over hesitation.

After two holidays centered on faith and tradition, they decide to treat what they found together as their own kind of miracle—something new, chosen, and real.

Characters

Miriam Brody

Miriam is introduced as someone who has learned to make herself small in a family that takes up all the oxygen in the room, and that quiet survival strategy shapes nearly everything she does at the start of Merry and Bright. She calls herself the overlooked “surprise baby,” and that label becomes a lens through which she interprets the constant interruptions, teasing, and casual dismissal she experiences—especially when her knowledge and competence should matter, like in food-related conversations where she actually has professional expertise.

What makes Miriam compelling is that her insecurity doesn’t translate into helplessness; she is, in reality, a founder and owner of a snack company, and she navigates work stress, logistics, branding, and distribution with the kind of responsibility that contradicts how her family “infantilizes” her. Her emotional arc is a shift from being grateful merely to be noticed to deciding she deserves to be respected and chosen, fully and openly.

Cal’s presence acts as a mirror that reflects the truth Miriam has been trained to ignore: her feelings are valid, her voice is worth hearing, and she isn’t asking for too much by wanting basic consideration. By the end, Miriam’s courage looks like insistence—she refuses to accept Cal’s belief that love can only exist after someone becomes “whole” again, and she chooses directness over retreat, running toward the relationship rather than settling back into being the person who quietly copes.

Calvin “Cal” Durand

Cal is built around contrasts: physically imposing and professionally famous, yet emotionally careful and almost painfully considerate, and that combination gives his character a steady warmth in Merry and Bright. His celebrity—an offensive lineman for the New York Giants—could have made him guarded or arrogant, but instead it seems to have trained him to be disciplined about what he reveals and how he occupies space around others.

He listens more than he talks, notices power dynamics instantly, and uses his presence not to dominate but to protect—whether that’s “buffering” Miriam from her family’s chaos or literally blocking a crowd so Ethan can catch chocolate gelt. The scar and the ACL injury aren’t just plot facts; they reinforce that his identity as an athlete is tied to vulnerability, impermanence, and recovery, which parallels his emotional healing.

The most defining element of Cal’s inner life is grief: his late wife’s death has turned Christmas into a minefield of memory, and he has been avoiding the season—and home—because it forces him to confront what he lost and who he is without her. Therapy is the quiet proof that he is trying, but his default instinct is still self-denial, believing he is only “half a person” and therefore not safe to love.

His romantic arc isn’t about moving on in a simplistic way; it’s about learning that grief can coexist with new love, and that choosing happiness again is not betrayal. When he shows up with the homemade charcuterie-and-cheese bouquet, it signals his shift from passive longing to active commitment: he stops letting fear make decisions for him, and he claims a future with Miriam as something he’s allowed to want.

Sarah Brody

Sarah functions as part of the loud gravitational pull of Miriam’s family life, and her character is defined less by malice than by habit and hierarchy in Merry and Bright. She contributes to the family’s constant motion—arriving with spouse and kids, participating in kitchen debates, and treating conversation like a sport where the loudest voice wins.

In that environment, Sarah often represents the sibling who doesn’t realize how sharp her casual dismissals can be, especially when Miriam offers opinions or expertise and gets talked over. Yet Sarah’s presence also helps illustrate why Miriam’s longing to be seen hurts so much: this is not a family without love, it’s a family with love that is unevenly distributed and often expressed in ways that overwhelm quieter people.

Sarah benefits from the existing family dynamic, so she has little incentive to question it, and that makes her an unintentional antagonist to Miriam’s emotional needs. Cal’s arrival subtly destabilizes this pattern by validating Miriam in real time, which puts pressure on Sarah—and the family—to notice what they’ve been ignoring.

Nina Brody

Nina, like Sarah, embodies the communal chaos that Miriam finds exhausting, but she also highlights a slightly different angle of sibling dynamics in Merry and Bright. Where Sarah’s energy reads as managerial and momentum-driven through her spouse and kids, Nina’s role is more about adding volume to the room—another adult voice that competes for attention and treats family time as a familiar, loud performance.

Nina’s significance comes from what she represents to Miriam: another reminder that Miriam has always had to compete to be heard, even among the people who are supposed to know her best. Nina doesn’t need to be overtly cruel to reinforce Miriam’s sense of being overlooked; small choices—brushing Miriam off in public, letting jokes land at Miriam’s expense, defaulting to the family narrative of Miriam as “little” or “cute”—are enough to keep Miriam in her assigned role.

Nina’s presence also makes Cal’s attentive steadiness stand out more sharply, because his calm is not just attractive, it’s corrective to the environment Miriam has normalized.

Jeremy

Jeremy is a connector character in Merry and Bright, someone who bridges Cal’s public identity with Miriam’s family world, and he uses that bridge with enthusiastic, well-meaning energy. He recognizes Cal as a football player and immediately wants to talk shop, which shows how quickly celebrity can reshape the social atmosphere in the room and how easily Miriam’s family shifts attention away from her.

At the same time, Jeremy isn’t portrayed as intentionally dismissive toward Miriam; he’s simply swept up in the thrill of proximity to someone famous, and that enthusiasm becomes part of the larger pattern Miriam is trapped inside. Jeremy’s accidental blurt about Cal’s late wife is one of his most important narrative functions, because it exposes how public Cal’s grief has become and how little control Cal has over when his private life enters a room.

The moment also underscores Jeremy’s human imperfection: he is not trying to hurt anyone, but his lack of discretion triggers tension, forces vulnerability, and pushes the story into its emotional truth.

Jenny

Jenny’s role in Merry and Bright is small but clarifying: she is the family’s competent voice of reason, and she briefly cuts through the chaos with practical authority. When Miriam burns her finger and Cal follows a trendy internet idea, Jenny’s medical knowledge grounds the scene, turning it from comedic panic into manageable reality.

Her presence highlights a recurring theme: in this family, the loudest reactions often take center stage, but actual expertise is what solves problems—an echo of Miriam’s experience of not being taken seriously despite knowing what she’s doing. Jenny also serves as a stabilizing force in the room during a moment when things could spiral emotionally, reinforcing that the Brody household contains care alongside chaos, even if it doesn’t always express that care in a way that nurtures Miriam.

Ethan

Ethan is the character through whom Merry and Bright shows Cal’s gentleness in action rather than in speech. As a ten-year-old nephew who refuses to join the scramble for parachuted chocolate gelt because he thinks it’s stupid, Ethan represents the kind of guardedness that can look like defiance but is often rooted in discomfort or fear of looking foolish.

Cal meets him at eye level—literally kneeling beside him—and uses something concrete and personal to connect: his job as an offensive lineman becomes a playful promise to protect Ethan’s space in the crowd. That interaction matters because it proves Cal’s instincts are protective without being patronizing, and it also gives Ethan a moment of triumph that feels earned rather than given.

Ethan’s excitement after catching the parachute becomes a miniature version of the book’s emotional logic: sometimes courage is easiest when someone trustworthy stands next to you and makes it feel possible.

Shells

Shells, the pet turtle, is more than a quirky detail in Merry and Bright; Shells is a symbol of the family ecosystem Miriam has grown up in, where even a turtle can compete for attention. The turtle’s existence reinforces Miriam’s long-standing belief that she is perpetually outshined, and the fact that Miriam includes Shells in her explanation of feeling overlooked shows how deep that wound runs—she isn’t only battling siblings and parents, she’s battling the family’s habit of making everything else louder than her.

Cal’s delight in meeting Shells is revealing because it shows how he participates in Miriam’s world without mocking it; he doesn’t dismiss her childhood stories as petty, and he treats the things that matter to her—even if they’re silly or small—as worth his attention. In that way, Shells becomes part of the romance: a tiny proof that Cal sees Miriam’s whole emotional landscape, not just the polished parts.

Judy Durand

Judy is a carefully controlled warmth in Merry and Bright, someone whose hospitality is genuine but shaped by a home environment that seems immaculate, highly decorated, and emotionally restrained. She welcomes Miriam quickly and insists she stay when the rain and flooding make travel unsafe, which reveals a maternal protectiveness that expresses itself through caretaking and practical decisions.

Judy’s fussing over Miriam in the morning and folding her into the rhythm of Christmas suggests she has been craving ease and joy in the house, but doesn’t quite know how to create it on her own in the shadow of Cal’s grief. She also reflects a different kind of family pressure than the Brodys: where Miriam’s family is noisy and intrusive, Judy’s world feels like it values composure, presentation, and tradition.

Miriam’s role as a “buffer” works partly because Judy is receptive to someone injecting warmth and stories into that structured atmosphere, implying that Judy is not cold—she’s simply used to a careful version of love.

Charles Durand

Charles complements Judy as part of the calm, curated family space Cal returns to in Merry and Bright. He comes across as welcoming and kind, but in a quieter, steadier way that matches the home’s controlled tone.

If the Brody household overwhelms through volume, the Durand household pressures through silence and expectation, and Charles embodies that by participating in tradition without creating chaos. His significance lies in what his presence communicates about Cal’s upbringing: a home where feelings may be managed rather than aired out, and where a tragedy like the loss of Cal’s wife could freeze the family in careful routines.

Charles’s acceptance of Miriam helps make the Christmas scenes feel restorative, because it suggests that Cal’s family isn’t rejecting joy—they’ve simply been waiting for a safe way back to it, and Miriam becomes a catalyst.

Themes

Family and Belonging

In Merry and Bright, family acts as both a comfort and a source of emotional conflict for Miriam and Cal, shaping how each understands love and identity. Miriam’s family, vibrant and loud, provides a sense of cultural grounding through their Hanukkah traditions, yet it also amplifies her insecurities.

Being the “surprise baby,” she constantly feels minimized—her career achievements overlooked, her opinions brushed aside, and her individuality swallowed by the collective energy of her family. Despite her affection for them, her visits evoke tension between her desire to belong and her need to be recognized as an adult with her own voice.

Cal’s relationship with family is the opposite in tone but similar in ache. His distance from his parents and avoidance of Christmas stem from unprocessed grief, where the weight of loss makes familial togetherness unbearable.

When the two come together, their contrasting experiences with family illuminate how belonging is not just about proximity but about being seen and accepted. Through their mutual agreement to “buffer” each other’s families, they unknowingly create the emotional bridge both have been missing—Miriam learns she can be loved without performing for attention, while Cal rediscovers that family can be a place of healing rather than pain.

The novel captures how love, loss, and family identity are deeply intertwined in the way people measure their worth and seek comfort during the holidays.

Healing and Emotional Renewal

Cal’s journey throughout Merry and Bright centers on emotional renewal after years of unresolved grief. His late wife’s death left him suspended in a half-life where professional focus masked personal emptiness.

The physical injury that ends his football season becomes symbolic—forcing him to slow down, confront vulnerability, and reenter spaces that evoke emotional memory. Meeting Miriam disrupts his quiet survival mode, allowing him to experience connection without the weight of expectation.

His admission that he feels like “half a person” reveals the core of his struggle: the fear that moving on would diminish the love he once had. Miriam’s compassion challenges that belief.

Her warmth, humor, and quiet resilience show him that healing does not erase love but expands its boundaries. Meanwhile, Miriam’s own emotional renewal unfolds through asserting her self-worth in a family dynamic that habitually sidelines her.

Cal’s attentiveness teaches her to expect respect and reciprocity in relationships, which she ultimately claims for herself when she rejects his narrative of brokenness. The novel portrays healing as an active process—one that involves confronting pain, embracing imperfection, and recognizing that love can be both a remembrance and a rebirth.

Identity and Self-Worth

Miriam’s insecurities about her place within her family mirror broader questions of self-worth and identity that the novel explores with emotional precision. Her position as the youngest sibling often reduces her to the family’s comic relief rather than its equal.

This dynamic bleeds into her professional life, where even her entrepreneurial success is undermined by the perception that she sells “little snacks.” Her partnership with Cal, although initially fabricated, becomes the context through which she begins to value her own voice. Cal’s consistent validation—his quiet support when her family interrupts her, his pride in her accomplishments—becomes a mirror reflecting a version of herself she rarely sees.

Over time, Miriam stops seeking external affirmation and begins asserting her worth independently. Her decision to confront Cal after he distances himself is the culmination of that growth; she refuses to let his fear define her story.

The novel frames self-worth as something cultivated through both introspection and relational reflection, showing how confidence often grows when someone finally feels seen for who they are rather than what they provide.

Love and Second Chances

Love in Merry and Bright is portrayed not as a sweeping romance that erases the past, but as a gentle recognition that two imperfect people can still build something meaningful after loss and disappointment. Cal’s relationship with Miriam emerges from mutual empathy rather than instant passion.

Both carry emotional histories that make them cautious—Miriam’s frustration with never being fully heard and Cal’s grief over his late wife’s memory. Their pretend relationship becomes a safe space for authenticity, ironically because it begins as a lie.

Through laughter, shared rituals, and small gestures—like Cal remembering to slip her cheese at the right moments—their connection transforms into something grounded and real. The novel insists that love is not about filling a void but creating room for new joy alongside old sorrow.

When Miriam tells Cal that love has made him “bigger, not smaller,” it captures the story’s emotional thesis: love’s power lies not in replacing what’s gone but in expanding one’s capacity to feel again. Their union at the end signifies not perfection, but a conscious choice to hope, to risk, and to begin again.

Faith, Tradition, and Cultural Harmony

The intersection of Hanukkah and Christmas in Merry and Bright becomes a setting for exploring how faith and cultural traditions can coexist without competition. The novel’s holiday backdrop serves as more than a seasonal device; it becomes a reflection of how belief systems and rituals help people navigate grief, connection, and renewal.

Miriam’s Hanukkah is rooted in community, noise, and sensory abundance—cooking, family arguments, and candlelight warmth. Cal’s Christmas, by contrast, is initially sterile and heavy with memory, defined by absence rather than joy.

When their celebrations overlap, both find meaning in each other’s rituals. Miriam’s presence reignites the spirit of celebration in Cal’s family, while Cal’s gentle integration into Hanukkah teaches Miriam that love can soften chaos without erasing it.

The shared observance of both holidays underscores a theme of harmony—faith not as dogma but as an emotional language that connects people to memory and hope. The story’s conclusion, framed by two holidays of light and miracles, suggests that faith’s true power lies in its ability to remind people that renewal is always possible, even in the shadow of loss.