A City on Mars Summary and Analysis

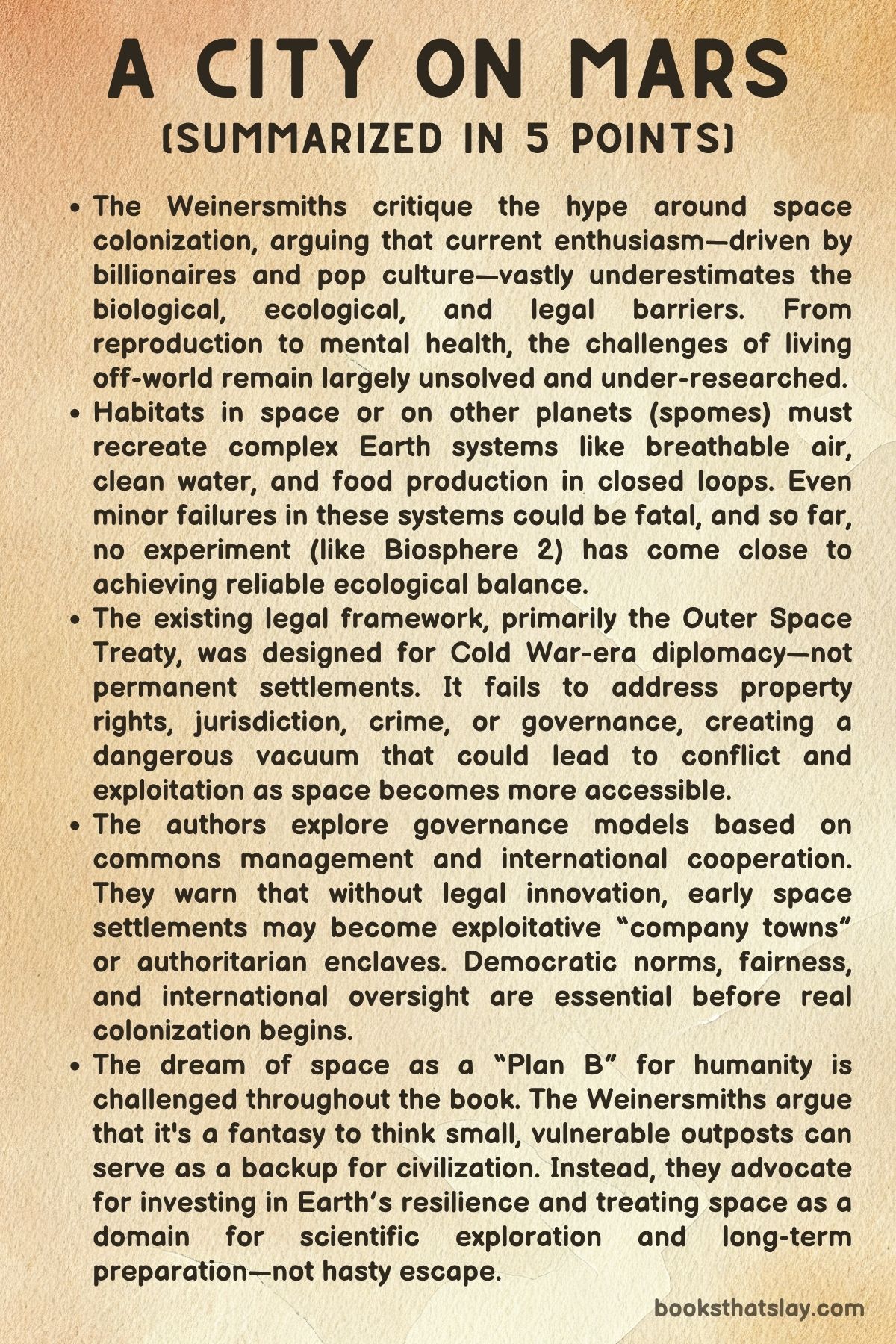

A City on Mars by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith is a skeptical, science-backed exploration of space colonization dreams. Written by cartoonist Zach Weinersmith and scientist Kelly Weinersmith, the book combines wit, deep research, and policy critique to evaluate whether humanity is truly ready to settle beyond Earth.

It’s not anti-space, but it is fiercely pro-reality. The authors dissect myths promoted by billionaires, sci-fi, and public enthusiasm, warning that existing biological, legal, and ecological challenges make near-term colonization wildly premature.

With a humorous yet serious tone, the book insists on clear-eyed thinking. Loving space should include being honest about its dangers, not romanticizing its prospects.

Summary

A City on Mars opens with a reality check. The Weinersmiths note the growing enthusiasm for human space settlement, but caution that this optimism often ignores enormous scientific and logistical challenges.

They set out to be “space bastards”—fans of exploration who nonetheless demand realism over fantasy. The early chapters focus on human biology and psychology.

Space is inherently hostile to the human body. Microgravity causes bone loss, vision problems, and muscle atrophy.

Radiation exposure is a long-term threat, with no easy shielding solutions. Space reproduction is largely unstudied—no human has ever conceived or birthed a child beyond Earth, and animal studies show troubling outcomes.

Psychological stress in isolated, confined environments also poses serious risks. Astronauts are elite and trained, yet even they experience conflict and emotional strain—ordinary settlers would fare worse.

The authors then examine potential locations for space settlements. The Moon, while close and promising for short-term outposts, presents toxic regolith, high radiation, and legal ambiguity.

Mars, often romanticized, has toxic soil, thin atmosphere, extreme cold, and massive infrastructure demands. Giant orbital habitats (like O’Neill cylinders) offer better environmental control but require building from scratch in space—an engineering feat far beyond current capabilities.

Other ideas, like Venusian cloud cities or asteroid settlements, are dismissed as even more speculative or impractical. Next, the book addresses the technical challenge of creating sustainable life-support systems.

Settlements must recycle air, water, food, and waste in closed ecological loops. This has never been accomplished successfully, not even in controlled experiments like Biosphere 2.

Creating these “spomes” (space homes) is daunting. One must manage energy, hygiene, mental health, privacy, and resilience, all without constant Earth support.

The legal landscape is another major obstacle. The foundational treaty of space law—the Outer Space Treaty of 1967—prohibits national claims on celestial bodies but is vague about private resource use.

Countries are already exploiting this ambiguity to pass their own laws. The failed Moon Agreement, attempts to regulate geostationary orbit, and hypothetical crimes like murder in space highlight how unprepared current legal systems are.

Governance, property rights, and criminal jurisdiction remain unresolved. In envisioning the future, the authors consider multiple paths.

They explore the idea of managing space as a commons, drawing inspiration from Earth-based models like the Antarctic Treaty or Law of the Sea. Yet space lacks the enforcement mechanisms, incentives, and trust needed for true cooperation.

If unregulated, it risks becoming a battleground of economic and geopolitical interests. The rise of “space-states”—de facto independent communities—could result in authoritarian systems, labor exploitation, or conflict with Earth-based powers.

One central myth the book deconstructs is the “Plan B” narrative—that space can serve as a backup for humanity. The authors argue this is implausible.

A viable settlement would require thousands of genetically diverse individuals, complete ecological self-sufficiency, and stable governance. No current plan meets these needs.

Moreover, small settlements could become isolated enclaves controlled by powerful entities, with no escape for their inhabitants. In the final chapters, the authors propose a radical alternative: maybe humanity doesn’t need to settle space in the near future.

Instead, focus should be on making Earth sustainable and resilient. Space should remain a domain for science, exploration, and careful, incremental development—not a desperate escape or colonial dream.

Throughout, the book combines sobering analysis with humor. “Nota Bene” interludes critique space movies, recount strange astronaut trivia, and mock future product placement in orbit.

These light-hearted moments reinforce the core message. Love space, but don’t lie to yourself about it.

Analysis

Kelly and Zach Weinersmith

As co-authors, Kelly and Zach present themselves not just as narrators but as protagonists in a broader intellectual journey. They adopt the self-deprecating label of “space bastards,” a term they use to define their skeptical but passionate stance toward space colonization.

Their personalities are distinct yet harmoniously woven into the text. Kelly brings scientific rigor as a biologist, grounding their analysis in hard data and caution, while Zach infuses the narrative with humor, cultural critique, and philosophical detours.

Their tone blends wit with seriousness, skepticism with wonder. They are relentless questioners, refusing to accept techno-utopian visions at face value and insisting on grappling with messy scientific, legal, and moral complexities.

They often interject with pop culture references or biting satire, making them feel like smart, sarcastic guides walking you through a high-stakes debate. More than just commentators, they are curators of uncertainty—advocating for intellectual honesty over ideological commitment.

The Archetypal Space Billionaire

Though no single billionaire is dissected in full detail, the authors collectively critique the class of wealthy tech entrepreneurs—like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos—who champion Mars colonization or orbital industry as a civilizational imperative.

This figure is depicted as a blend of visionary and marketer, someone who evokes frontier mythology, sells techno-optimism, and often skips over the deep scientific and ethical hurdles.

In the Weinersmiths’ portrayal, the space billionaire is both admirable and dangerous. Admirable for ambition and risk-taking, but dangerous for promoting an illusion of readiness and glossing over sociopolitical and biological complexity.

This character serves as a foil to the authors’ more measured, empirical stance. They are an avatar of confidence untethered from ecological systems thinking, a modern Ahab chasing a red-planet whale.

The Idealized Astronaut

Another recurring character in the narrative is the elite astronaut, portrayed not just as a real person but as a symbolic standard by which space viability is too often judged.

The authors are quick to point out that astronauts—highly trained, psychologically screened, physically elite—are not representative of the general population.

In this light, the astronaut becomes a character of contrast. A model of resilience that hides the fragility of average humans.

While the authors respect astronauts’ achievements, they argue that drawing lessons for long-term, multi-generational settlements from a few handpicked people living in low Earth orbit is scientifically misleading. The astronaut is cast as both a hero and a red herring.

The Unseen Settler

Looming throughout the book is the imagined space settler—a future person or family who would attempt to live, work, and reproduce in a lunar base, a Martian dome, or a rotating O’Neill cylinder.

This character is not fully formed, because—critically—such a person does not yet exist.

The authors focus on how little we know about what life would actually be like for this person. The unseen settler is vulnerable to radiation, trapped in psychological stress, poorly supported by law, and at risk of social isolation or exploitation.

They are the human at the end of a very long line of techno-political decisions. The authors constantly ask: who is this settlement really for, and at what cost?

The Bureaucratic Technocrat

This subtle but recurring figure is present in discussions of NASA, space agencies, and regulatory frameworks. They appear as someone often well-meaning but constrained by politics, legacy assumptions, and public relations pressures.

These characters are the ones who might quietly increase the oxygen in Biosphere 2, avoid doing reproduction experiments due to ethics panels, or fail to account for female physiology in early astronaut gear.

They symbolize the inertia and blind spots in institutional thinking. The authors portray them with a mixture of empathy and critique.

They acknowledge the difficult constraints they face while pointing out that bureaucratic caution or omission can create massive knowledge gaps in mission-critical areas.

The Cautionary Historian

This is a voice—sometimes echoed by the authors, sometimes quoted from scholars—who reminds readers of Earth’s historical parallels. Colonization, frontier myths, legal loopholes, company towns, and geopolitical standoffs reappear in discussions of how humanity might behave in space.

The cautionary historian is a ghost from Earth’s past, holding up a mirror to space ambitions. Whether it’s the fate of the Moon Agreement or the echoes of Antarctic violence, this character reveals the risks of repeating old mistakes in a new domain.

This figure is the moral compass of the book. It helps readers weigh ethical and governance issues beyond the bounds of technology.

Analysis of Themes

The Inhospitable Reality of Space Environments

One of the central themes in A City on Mars is the sheer physical hostility of space and extraterrestrial environments. This starkly contrasts with the adventurous, often romanticized visions of space colonization.

The book presents overwhelming evidence that space is not a natural habitat for humans. Every attempt to survive there will require solving monumental problems in biology, physics, engineering, and psychology.

Space lacks breathable air, stable temperatures, atmospheric pressure, and gravity—all of which are essential to human life. Microgravity leads to rapid bone density loss and muscle atrophy.

Cosmic radiation, barely shielded by thin planetary atmospheres like Mars’, can damage DNA, increase cancer risk, and degrade electronics. Basic movement, such as operating in a space suit, becomes a high-effort, high-risk task.

Reproductive biology is almost entirely untested in these conditions. Early data suggest profound risks to fertility and fetal development.

These biological limitations are not just inconveniences; they pose existential threats to long-term human presence in space. Earth’s ecosystem—providing clean air, water, and biodiversity—is a product of billions of years of evolution.

Trying to replicate even a small fraction of Earth’s systems in space habitats is daunting. Even with advanced machines and recycling systems, the ecological and physiological gaps remain vast.

The authors dismiss the idea that a few clever machines will solve these challenges. Instead, they call for humility, realism, and far more research before humanity considers permanent off-world living.

The Mythology and Motivations Behind Space Settlement

Another recurring theme in A City on Mars is the critique of ideological and cultural narratives that propel space colonization. The book scrutinizes the rhetoric surrounding humanity’s “destiny” to expand into the cosmos.

The justifications often cited—survival, exploration, economic growth, or spiritual transformation—are portrayed as more rhetorical than rational. The “Plan B” concept is one such example.

The authors dismantle the idea that space can serve as an escape hatch from Earth’s crises. Despite its issues, Earth remains vastly more habitable than the Moon or Mars.

Establishing even marginal life-supporting settlements off-world requires effort and resources that far exceed what would be needed to repair Earth’s ecosystems. This makes space escape plans both unrealistic and irresponsible.

The book also critiques the notion that exploration is a universal human imperative. Not all cultures have glorified expansionism, and history shows exploration often benefits elites, not the collective population.

Similarly, the “overview effect”—the idea that seeing Earth from space inspires peace and cooperation—is treated with skepticism. Astronaut behavior post-mission often reflects mundane or flawed human tendencies.

The authors argue that much of the pro-space rhetoric functions as secular mythmaking. Space is framed as a techno-utopia or moral crucible, but these visions rarely align with evidence.

Instead of blindly following these narratives, the authors advocate for critical reflection. They challenge readers to distinguish between poetic aspirations and material realities.

The Technological and Ecological Challenges of Self-Sustaining Habitats

A City on Mars devotes considerable attention to the massive technological and ecological hurdles involved in creating sustainable space habitats. These structures—called “spomes”—must operate as entirely closed-loop ecosystems.

Such habitats are not plug-and-play systems. They must mimic the Earth’s delicate balance of oxygen, carbon dioxide, water, food, and microbial ecosystems.

Even on Earth, projects like Biosphere 2 faced serious failures. These included oxygen drops, CO₂ spikes, and social breakdown among participants—despite the presence of backup support.

In space, the stakes are higher. Failing to filter water, manage waste, or recycle air could lead to catastrophe.

The recycling of bodily waste into usable resources requires sophisticated processing and constant oversight. Food production through hydroponics or bioreactors demands energy, infrastructure, and human labor.

Solar energy may be abundant in space but is limited by location and subject to interference, like lunar dust or Martian storms. Nuclear power is powerful but fraught with safety and political concerns.

The human factor also complicates design. Habitats must account for social, emotional, and psychological needs in cramped, high-stress conditions.

Early space homes will be far from glamorous. They’ll resemble utilitarian bunkers more than the glass-domed utopias depicted in science fiction.

The authors emphasize that engineering alone cannot overcome the ecological and human complexities of living in space. Without careful, long-term development, spomes are likely to be fragile, dangerous, and unsustainable.

The Fragility and Obsolescence of Space Law

A City on Mars also explores the outdated and fragile legal framework that governs outer space. Existing treaties like the Outer Space Treaty (OST) were drafted during the Cold War.

The primary concern at the time was preventing nuclear conflict, not managing long-term settlement or private enterprise in space. As a result, today’s laws are woefully unprepared for the realities of colonization.

The OST bans national appropriation of celestial bodies but allows resource extraction. This contradiction creates a legal gray area.

Without enforcement mechanisms or clear jurisdiction, disputes over ownership, mining, and governance are likely to escalate. The legal system lags far behind technological and commercial ambitions.

The failure of the Moon Agreement—which aimed to equitably distribute space resources—further illustrates the problem. Major powers refused to participate, rejecting any system that might curtail their advantage.

Questions about criminal jurisdiction also arise. If a crime is committed on Mars by a multinational crew, determining which nation’s laws apply becomes a logistical and ethical quagmire.

The book stresses that space law is not a niche issue. It’s foundational to ensuring peace, justice, and safety in future settlements.

The authors argue that new international frameworks must be created before permanent human habitation begins. Otherwise, we risk legal chaos, conflict, and exploitation mirroring Earth’s colonial past.

Law, they argue, is as vital as oxygen for a functioning space society. Without robust legal structures, space settlements are doomed to instability and injustice.

The Political and Ethical Consequences of Space Expansion

The political and ethical dimensions of space colonization are given sharp focus in A City on Mars. The authors warn that space is not a blank canvas but an extension of existing power structures.

Early settlements will likely be funded and controlled by states or corporations. This creates a dynamic similar to company towns, where autonomy and freedom are limited by dependence.

Settlers may be economically coerced or politically subjugated. With no way to leave, their rights and welfare hinge entirely on those who hold power.

Population scale is another issue. To be viable, settlements need thousands of genetically diverse individuals—not a dozen elite astronauts.

The infrastructure to support large, self-sufficient populations is currently nonexistent. Medical care, food production, education, and governance all remain unresolved challenges.

Furthermore, space may become a new arena for geopolitical rivalry. Control over lunar water, orbital infrastructure, or surveillance satellites could translate into Earth-bound leverage.

Rather than reducing existential risks, space expansion could create new ones. Settlements might rebel or be used as platforms for aggression.

The authors also question the ethics of escapism. Selling the dream of space can distract from solving Earth’s pressing problems—climate change, inequality, and governance.

Space should not be an excuse to abandon Earth. It must be approached responsibly, with frameworks that prioritize justice, sustainability, and human dignity.

In their view, the future of space colonization must be shaped not by profit or power but by collective, inclusive decision-making. Otherwise, we risk repeating the darkest patterns of our terrestrial history.