A Handful of Dust Summary, Characters and Themes

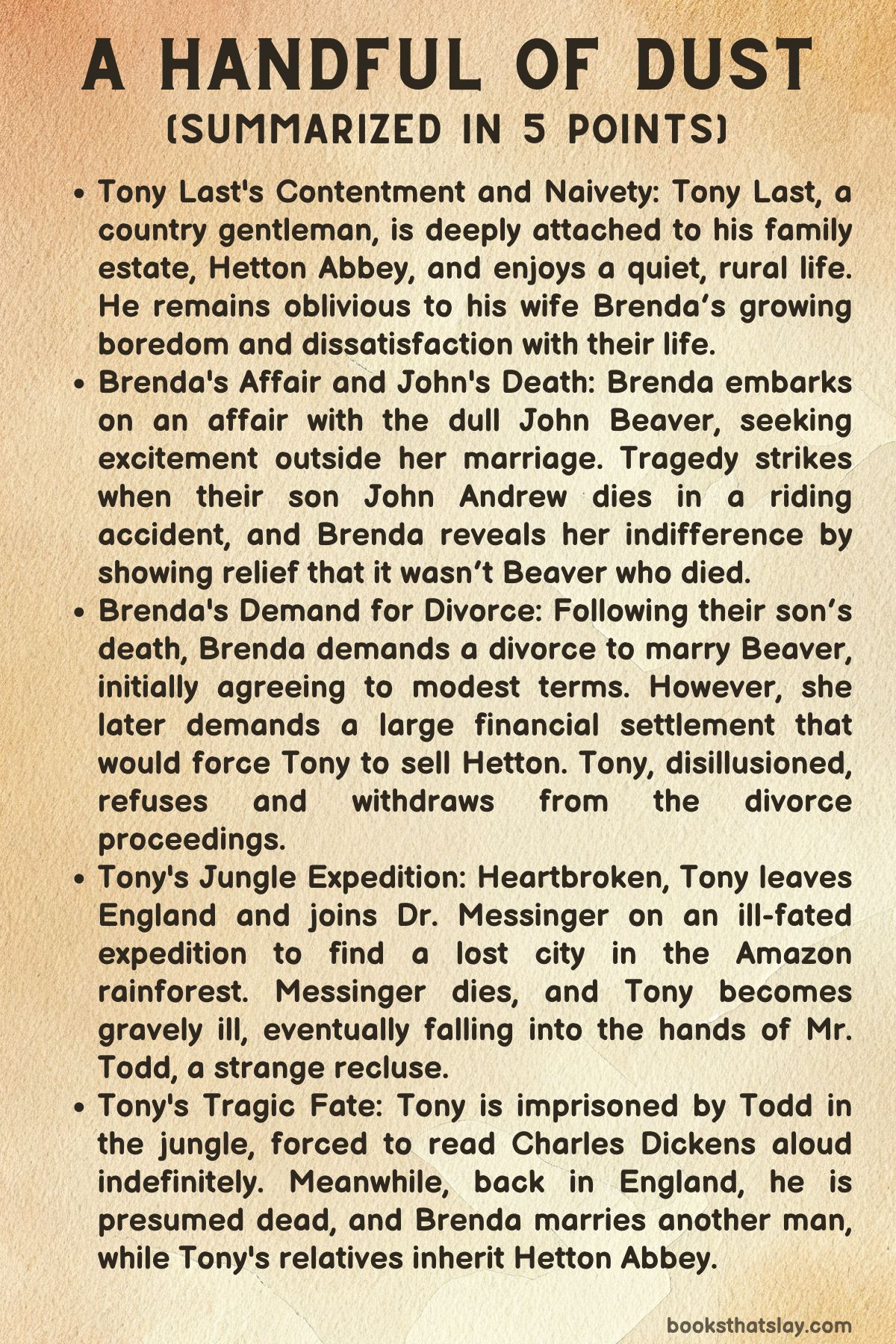

A Handful of Dust, written by British author Evelyn Waugh, is a darkly satirical novel that explores the crumbling world of the English aristocracy in the early 20th century. First published in 1934, the novel blends biting social critique with a tragic narrative, following Tony Last, a country squire whose once-idyllic life unravels when his wife embarks on a careless affair.

The story takes an unexpectedly grim turn when Tony ventures into the South American jungle, leading to his nightmarish entrapment. Waugh’s work, with its mix of sharp humor and bleak tragedy, reflects his own personal struggles during that period.

Summary

Tony Last, a country gentleman, lives a seemingly contented life with his wife Brenda and their young son, John Andrew, in Hetton Abbey, their family estate.

Tony is deeply devoted to the estate, which, though aesthetically unremarkable and mocked by others as a “Victorian Gothic monstrosity,” holds great personal significance for him. His love for the rural, peaceful existence blinds him to the growing dissatisfaction of his wife, who finds their life tedious.

Brenda, feeling trapped in her marriage, meets John Beaver, an unremarkable and socially insignificant man.

Despite her lack of genuine affection for him, she begins an affair, lured more by the excitement of change than by any deep emotional connection. Brenda spends increasingly more time in London, living a dual life, and persuades Tony to fund a small flat for her under the guise of social engagements.

Unbeknownst to Tony, her affair becomes common knowledge among their social circle, while Tony remains oblivious. He even fails at his friends’ attempts to set him up with a mistress.

Tragedy strikes when John Andrew is killed in a horse-riding accident. Brenda, mistakenly thinking her lover Beaver is the one who has died, briefly reveals her apathy toward her family by exclaiming relief when she discovers it is her son.

Her cold response shatters any remaining illusion of her devotion to Tony or their life together.

After the funeral, Brenda coldly announces her desire for a divorce to marry Beaver. Though devastated, Tony agrees to shield her reputation by offering a dignified divorce and a modest annual allowance of £500.

However, her greed escalates when Beaver influences her to demand £2,000 annually, a sum that would force Tony to sell Hetton Abbey.

Faced with Brenda’s betrayal, Tony realizes the extent of his naivety. Luckily, a technicality involving the woman Tony hired to stage adultery in Brighton allows him to avoid the divorce proceedings.

Disillusioned, Tony decides to leave England on a six-month expedition, denying Brenda any financial settlement. With no future prospects with Tony, Beaver promptly abandons her.

Tony joins an explorer, Dr. Messinger, on a quest to locate a lost city deep in the Brazilian jungle. The journey, however, quickly spirals into disaster due to Messinger’s incompetence.

Their native guides desert them, leaving the two stranded. When Tony falls seriously ill, Messinger sets off alone to find help but dies in the attempt.

Tony, left behind, is rescued by Mr. Todd, an eccentric recluse who lives in the jungle. Todd nurses Tony back to health, but instead of releasing him, he traps Tony in his home, forcing him to read aloud from Dickens’ works indefinitely.

When a search party from England arrives, Todd hides Tony, misleading the rescuers into thinking Tony is dead.

Back in England, Tony is presumed dead. His estate passes to his relatives, and Brenda marries another man, while Tony remains a prisoner in the jungle, forever reading Dickens.

Characters

Tony Last

Tony Last is the protagonist of A Handful of Dust. He is a country gentleman who embodies the old-fashioned values of English aristocracy, holding deep pride in Hetton Abbey, his family’s ancestral home.

His attachment to the house represents his connection to tradition and stability, though it is an illusionary security. Tony is oblivious to the inner dissatisfaction of those around him, including his wife, Brenda. He remains blindly content with his rural life and routine, even as his marriage deteriorates.

His emotional naivety and idealism make him a tragic figure, one whose reality unravels painfully. His journey from the comfort of Hetton to the depths of the Amazonian jungle reflects his personal disintegration.

As his life spirals into chaos, the futility of his romantic ideals and loyalty becomes apparent. His eventual fate, trapped in the jungle reading Dickens to a crazed recluse, reveals the bitter irony of his passive existence. He becomes literally imprisoned by stories, just as he was figuratively imprisoned by his illusions back home.

Brenda Last

Brenda Last, Tony’s wife, is a restless and selfish character, bored with the limitations of her provincial life at Hetton. Her dissatisfaction drives her into an affair with the insignificant and shallow John Beaver.

Brenda’s lack of depth is highlighted by her attraction to such a dull man, suggesting that she craves any escape from her monotonous life, even at the cost of her integrity. Her betrayal of Tony and her callous reaction to her son’s death reveal the extent of her emotional detachment.

Brenda’s superficial nature is further exposed when she attempts to demand a financial settlement after the breakdown of her marriage. She shows complete disregard for the values that Tony holds dear.

After Beaver abandons her, she marries one of Tony’s friends, reflecting her moral shallowness. Brenda is a figure of modernity in contrast to Tony’s attachment to the past, but her portrayal is unflattering, highlighting her moral vacuity.

John Beaver

John Beaver is an uninspiring and dull character, whose primary trait is his insignificance. He is emblematic of a shallow, directionless social climber, attaching himself to wealthier people to survive in society.

His affair with Brenda is marked not by passion or connection but by his willingness to be used by her, indicating his passive, parasitic nature. Beaver lacks ambition, personality, or substance, and his relationship with Brenda is transactional.

When Tony withdraws financial support from Brenda, Beaver promptly loses interest in her, further emphasizing his superficiality. He is a symbol of the moral and emotional emptiness of a certain class of society, driven by social survival rather than any meaningful engagement with life or people.

Mrs. Beaver

Mrs. Beaver, John Beaver’s mother, is a hard-nosed, pragmatic businesswoman. She profits from the personal and social misfortunes of others.

As the owner of a furniture and interior design business, Mrs. Beaver is concerned only with her business interests, representing the mercantile side of London society. She exemplifies a cold, opportunistic outlook, capitalizing on the needs and weaknesses of others for her own gain.

Her character contrasts with Tony’s idealism, reinforcing the theme of encroaching modern values based on commerce and self-interest.

John Andrew

John Andrew, Tony and Brenda’s son, is a relatively minor character in terms of direct narrative presence. However, his death plays a pivotal role in the novel.

His fatal riding accident shifts the novel from comedy into tragedy. His death exposes Brenda’s selfishness and further cements the emotional distance between Tony and her.

John Andrew’s death also serves as a catalyst for Tony’s emotional disillusionment, forcing him to confront the reality of his life and marriage. Brenda’s indifferent reaction deepens her portrayal as a shallow, self-absorbed character.

Dr. Messinger

Dr. Messinger is the explorer who persuades Tony to join his doomed expedition to the Amazon rainforest. Messinger is depicted as incompetent and naïve, embodying the romanticized but flawed notion of exploration.

His inability to control the native guides and mismanagement of the expedition leads to their mutual downfall. While Messinger may represent an adventurous spirit, his character serves to highlight the danger of hubris and misplaced confidence in uncharted territories.

His death, swept away over a waterfall, is the final act of his ineffectual leadership, leaving Tony to fend for himself in the wilderness. Messinger’s failure is symbolic of the false hopes and delusions that pervade the novel, mirroring Tony’s own journey of disillusionment.

Mr. Todd

Mr. Todd is the enigmatic and sinister figure who rescues Tony in the jungle, only to imprison him in a bizarre form of literary captivity. Although outwardly a benevolent figure, Todd’s true nature emerges as he forces Tony to read Dickens aloud indefinitely.

His illiteracy and obsession with Dickens represent a grotesque, distorted version of cultural and intellectual engagement. Todd’s isolated world in the jungle becomes a metaphor for Tony’s own isolation from reality, and his control over Tony mirrors the novel’s theme of passive submission to external forces.

Todd’s character may also be seen as a symbol of colonialism, where the European, in this case Tony, is subjugated in a foreign land. Tony is stripped of power and agency in Todd’s strange world.

Thérèse de Vitré

Thérèse de Vitré is a brief but significant figure who represents an unattainable ideal for Tony. She is a young Roman Catholic girl whom Tony meets on his journey to Brazil.

Their shipboard romance is quickly cut short by her devout religious beliefs. Thérèse’s Catholicism contrasts with Tony’s disillusioned and failing life, and her rejection of him further accentuates his emotional isolation.

Her character highlights the theme of unattainable purity and virtue, standing in stark opposition to the moral decay Tony faces in his own life.

Themes

The Collapse of Traditional English Aristocracy and the Illusions of Class Identity

Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust presents a vivid critique of the decline of traditional English aristocracy, symbolized through Tony Last and his attachment to Hetton Abbey. Hetton, an architectural monstrosity to everyone except Tony, becomes a symbol of the fading past—representing outdated values, moral rigidity, and a way of life that is irrelevant in the modern world.

Tony’s inability to recognize the absurdity of maintaining such a monument to a bygone era reflects his denial of the changing social dynamics around him. His deep attachment to Hetton signifies a larger, cultural nostalgia for the English gentry’s former glory, a class now being eroded by modernity and bourgeois values.

This tension between an unyielding past and an emerging modernity is starkly illustrated by the way Brenda and her social circle, who operate within a more pragmatic, materialist mindset, treat Tony’s adherence to tradition as laughable. As Tony clings to the ideals of honor and loyalty, exemplified by his willingness to financially support Brenda even after her betrayal, the novel reveals the cracks in the aristocratic class’s illusions of grandeur and nobility.

His ultimate abandonment in the jungle mirrors his detachment from a society that no longer values his ideals or his way of life. The novel is, thus, a lament for the collapse of a world in which class, tradition, and ancestry were the cornerstones of identity, displaced by a new world driven by selfishness, consumerism, and opportunism.

The Impotence of Moral and Social Codes in a Fragmenting Modern Society

Waugh critiques the impotence of traditional moral codes in a society that increasingly disregards ethical obligations in favor of personal gratification and superficial appearances. Tony’s moral rigidity and adherence to the codes of honor, faithfulness, and integrity seem quaint and almost irrelevant in a world where characters like Brenda and Beaver navigate relationships as transactional, using emotional connections for social mobility or financial gain.

Brenda’s affair with Beaver, and her willingness to destroy Tony emotionally and financially in the divorce negotiations, reveals the crumbling of these moral structures. In this fragmented modernity, relationships become commodities, and individuals prioritize their own comfort over any sense of communal or familial duty.

The starkest example of this collapse is Brenda’s chilling response to her son’s death—her initial relief that it might have been Beaver rather than her child. Waugh depicts a world where traditional values—marital fidelity, parental responsibility, and even human decency—are hollowed out, leaving behind an existential void that characters like Tony fail to navigate.

Tony’s journey to the Amazon jungle becomes a physical manifestation of his moral exile, as he transitions from a society that no longer has a place for his values to an environment where survival, not ethics, becomes the only guiding principle.

Satire of British Imperialism and the False Romanticism of Exploration

Waugh uses Tony’s disastrous expedition to Brazil as a sharp satire of British imperialism and the romanticized notions of exploration that often accompanied it. The journey, motivated by Tony’s desire to escape the crumbling reality of his personal life, reflects the futility and delusion that characterized much of the British imperial project.

Dr. Messinger, with his ill-prepared and haphazard approach to the jungle, represents the incompetence that often underpinned colonial endeavors. The lost city that Tony seeks becomes a symbol of the hollow idealism behind British expansion into foreign territories, where explorers projected their desires for discovery and conquest without understanding the realities they would face.

Tony’s eventual entrapment by Mr. Todd further illustrates the absurdity of British superiority in foreign lands. Stripped of his social position and all the trappings of his former life, Tony is reduced to little more than a reading servant in the jungle, an irony that highlights the tenuousness of the colonialist assumption that British identity could maintain its coherence and power in the face of the unknown.

Waugh’s critique also extends to the myth of exploration itself, as Tony’s aimless and mismanaged adventure contrasts sharply with the controlled, dignified imperialist narratives of conquest and civilization that dominated British cultural imagination. Instead, exploration is shown as a vehicle for personal disillusionment and existential despair, leading Tony not to glory but to servitude and oblivion.

Existential Disintegration and the Absurdity of Human Existence

A Handful of Dust is permeated by existential disillusionment, where the characters’ lives unravel into chaos, absurdity, and, ultimately, meaninglessness. Waugh exposes the precariousness of human existence, especially as Tony’s seemingly structured and idyllic life collapses with tragic speed.

The novel’s title, drawn from T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, evokes a sense of existential decay and suggests that beneath the veneer of social rituals and moral codes lies a fundamental emptiness. Tony’s descent into the Brazilian jungle becomes a metaphor for the absurdity of human existence.

Stripped of societal expectations and comforts, Tony is reduced to a helpless pawn in Todd’s demented world, forever condemned to read Dickens to a maniac who has no use for him beyond this absurd ritual. Waugh evokes the absurdism of Kafka, where fate, arbitrary and cruel, controls the lives of individuals, rendering all human attempts at control or order laughable.

Tony’s eventual imprisonment in the jungle underscores the notion that life offers no inherent meaning; instead, individuals are often at the mercy of chaotic and senseless forces that obliterate their aspirations. This existential absurdity is mirrored in the characters’ futile attempts to find meaning through wealth, social standing, and relationships, only to end in failure, disillusionment, and existential despair.

Waugh’s narrative hints at the futility of attempting to impose order or purpose on life, as Tony’s entrapment becomes a symbol of the larger absurdity of existence itself, an existence governed by randomness, selfishness, and the illusion of control.

Disintegration of Personal and Collective Identity in a Modern, Secular World

Throughout the novel, Waugh examines the disintegration of both personal and collective identity in a rapidly modernizing, secular world. Tony Last’s identity, initially rooted in the tradition of land ownership, family, and a moral code derived from a fading aristocratic order, crumbles under the pressures of modernity, urban materialism, and emotional betrayal.

His detachment from Hetton Abbey, symbolically and literally, marks the severing of ties with his past and the values that once defined him. Brenda’s identity, in contrast, is shaped not by internal values but by external validation from her social circle and her superficial pursuit of pleasure and wealth, which leaves her hollow and disillusioned.

The novel also portrays the broader erosion of collective identity, where community, family, and social responsibility disintegrate under the pressures of individualism and consumerism. Hetton Abbey, with its declining fortunes and loss of relevance, becomes a microcosm for the decline of the collective values that once held British society together.

This suggests that modern secularism and the abandonment of tradition result in a fragmented, aimless existence.