Agamemnon Summary, Characters and Themes

“Agamemnon” is a Greek tragedy written by the ancient playwright Aeschylus. It is the first play in a trilogy known as the Oresteia, which also includes “The Libation Bearers” and “The Eumenides”.

The play tells the story of Agamemnon, the king of Argos, returning home from the Trojan War. His wife, Clytemnestra, has been waiting for his return, seeking vengeance for Agamemnon’s sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia before the war. Clytemnestra, along with her lover Aegisthus, plots to kill Agamemnon upon his return. The play explores themes of justice, revenge, and the consequences of violence.

Summary

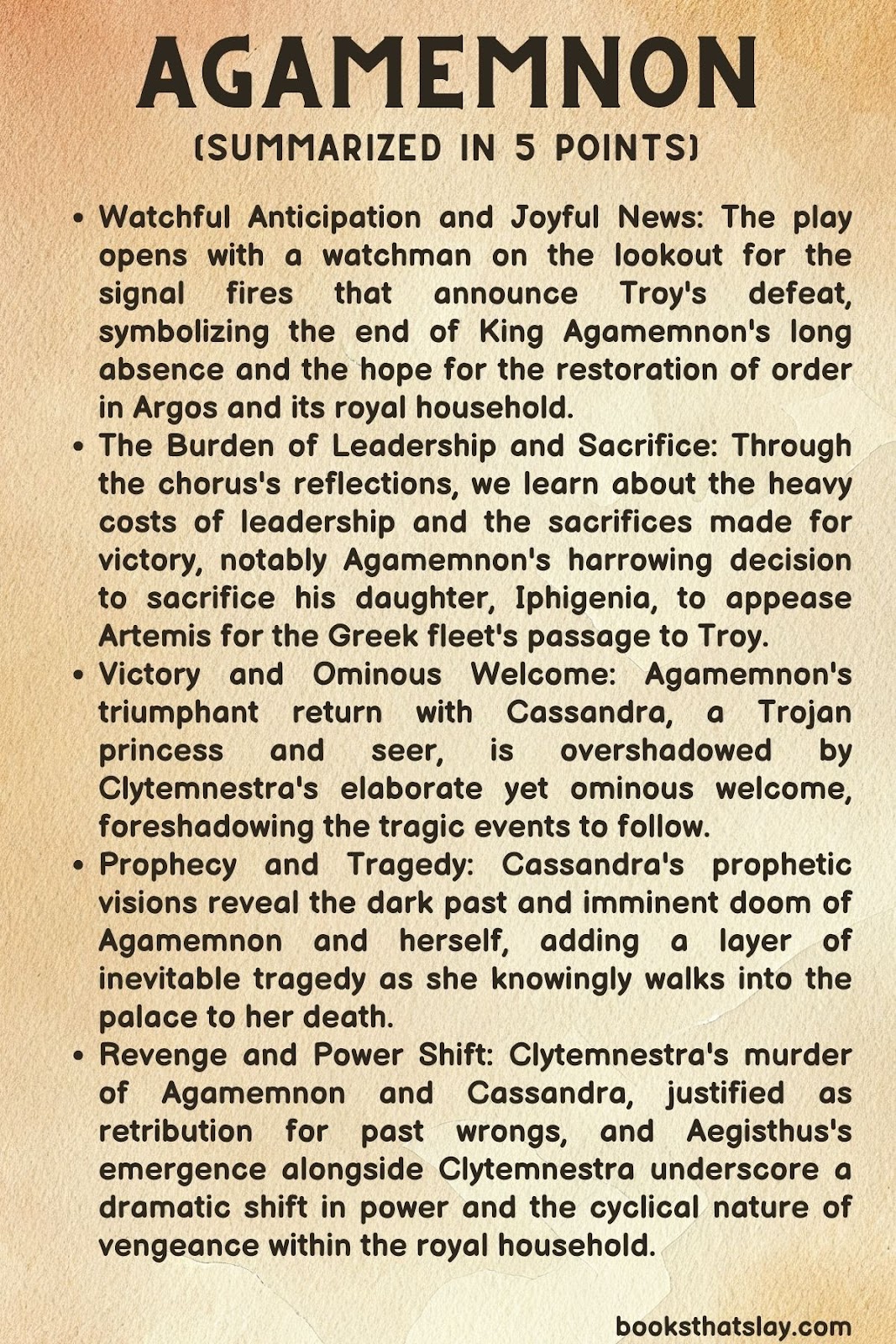

The tale unfolds with a watchman perched atop the palace, keenly awaiting the signal fires that would herald Troy’s defeat.

Assigned by Clytemnestra, he yearns for King Agamemnon’s return to restore order to Argos and its royal house, disrupted during the king’s long absence at the Trojan War. His vigil ends in joy as he spots the fires, signaling Troy’s fall and Agamemnon’s imminent return.

The chorus of Argive elders enters, singing the parodos and recounting the origins of the conflict: Agamemnon and Menelaus’s expedition to avenge Paris’s abduction of Helen, which led to Agamemnon’s harrowing sacrifice of his daughter, Iphigenia, to appease Artemis.

They reflect on the divine justice meted out to Troy, yet worry about the state of Agamemnon’s house, hopeful yet anxious for the future.

Clytemnestra then appears, announcing Troy’s conquest through the beacon fires, vividly describing their journey to Argos. Following her departure, the chorus’s first stasimon celebrates the city’s fall, crediting Zeus for avenging the Trojans’ moral decay, symbolized by Paris and Helen, while mourning the heavy Greek losses.

The narrative intensifies with the herald’s entrance, confirming Agamemnon’s victory and return, amidst Clytemnestra’s joy. He recounts the Greek fleet’s destruction by a storm post-Troy, leading into the chorus’s second stasimon that condemns Helen and praises divine retribution.

Agamemnon’s arrival with the Trojan seeress Cassandra marks a turning point. Clytemnestra’s grand welcome, persuading him to tread on crimson tapestries as a symbol of honor, foreshadows tragedy. The chorus, sensing doom, reflects on impending disaster in their third stasimon.

Clytemnestra’s attempt to welcome Cassandra into the palace fails as the seeress, foreseeing their deaths, prophesies the house’s cursed history and her own fate. Despite the chorus’s empathy, they fail to grasp her ominous predictions. Cassandra’s resignation to her fate leads her inside, to her death.

The chilling aftermath unfolds as Agamemnon’s cries echo from the palace. The chorus, torn in debate, hears Clytemnestra boast over the corpses of Agamemnon and Cassandra, justifying her actions as retribution.

Aegisthus, Agamemnon’s cousin and Clytemnestra’s accomplice and lover, reveals his role in the murder, coercing the chorus to accept their rule, sealing the tragic fate of Agamemnon’s house.

Characters

Agamemnon

The king of Argos, Agamemnon is a complex character who returns victorious from the Trojan War only to face his tragic demise.

His decision to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia years before sets off a chain of events that ultimately lead to his murder by his wife, Clytemnestra.

Clytemnestra

Agamemnon’s wife, Clytemnestra, is a powerful and cunning character who masterminds the murder of her husband.

Her actions are driven by a desire for revenge against Agamemnon for sacrificing their daughter, Iphigenia, and possibly by her adulterous relationship with Aegisthus. She justifies her actions as retribution and assumes control over Argos with Aegisthus.

Cassandra

A Trojan princess and seeress, Cassandra is taken as a war prize by Agamemnon. She possesses the gift of prophecy, cursed so that no one believes her predictions.

She foresees her own death and that of Agamemnon but is powerless to prevent it. Her character embodies the tragedy of foresight without the power to change the future.

Aegisthus

Cousin to Agamemnon and Clytemnestra’s lover, Aegisthus has his own vendetta against Agamemnon, stemming from a family feud.

He assists Clytemnestra in the king’s murder and claims the throne of Argos alongside her. Aegisthus represents the continuation of the cycle of vengeance and the corrupting influence of power.

The Chorus

Composed of the elders of Argos, the chorus serves as a moral and reflective voice throughout the play. They provide background information, comment on the action, and express the communal anxiety and moral dilemmas faced by Argos in the wake of the Trojan War and Agamemnon’s return.

Their loyalty to the house of Agamemnon is tested as they witness its downfall.

The Watchman

The watchman opens the play, tasked by Clytemnestra to watch for the signal fires announcing Troy’s fall. His relief at the news of Agamemnon’s return is palpable, setting the stage for the unfolding tragedy.

He represents the common people’s perspective, caught between hope for peace and the ominous reality of the royal household’s dynamics.

The Herald

The herald brings news of Agamemnon’s return and the Greek victory at Troy to Argos. His arrival intensifies the drama, as it heralds the beginning of the play’s tragic climax. He also reports the destruction of the Greek fleet by a storm, highlighting the theme of divine retribution that runs throughout the play.

Themes

1. The Relationship of Justice to Retribution

At the heart of “Agamemnon” lies the theme of justice and its dark counterpart, retribution.

Aeschylus examines the cyclical nature of violence and the pursuit of justice through the lens of the House of Atreus, a dynasty cursed with bloodshed. The sacrifice of Iphigenia by Agamemnon serves as a grim reminder of the price of war and the demands of divine appeasement, setting the stage for Clytemnestra’s act of vengeance.

Clytemnestra’s murder of Agamemnon, while portrayed as an act of personal and maternal retribution for Iphigenia’s death, raises profound questions about the nature of justice.

Is it merely a cloak for revenge, or does it serve a higher moral order?

Aeschylus does not provide easy answers but instead presents the complexities of human actions and their justifications under the guise of justice.

2. The Inescapability of Fate

Fate, as a predetermined course that mortals are powerless to avoid, casts a long shadow over the characters of “Agamemnon.”

The concept of moira, or fate, is not just a backdrop but a driving force that propels the characters toward their inevitable end. Agamemnon’s fate is sealed the moment he sacrifices Iphigenia, triggering a chain of events that lead to his own demise.

Cassandra’s prophetic visions, imbued with the certainty of fate, underscore the tragic inevitability that haunts the royal house.

Aeschylus explores how fate intertwines with the characters’ choices, suggesting that while destiny is inescapable, it is the characters’ actions, often in response to or in anticipation of fate, that fulfill their doomed legacies.

3. The Interdependence of Hope and Fear

Throughout “Agamemnon,” hope and fear are not merely emotions experienced by the characters but thematic pillars that reflect the human condition.

The chorus, representing the collective voice of Argos, oscillates between hope for Agamemnon’s triumphant return and fear of what his return might unleash. This duality mirrors the precarious balance between aspiration and anxiety that defines the human experience.

Aeschylus masterfully portrays hope and fear as two sides of the same coin, each giving rise to the other. The hope for a better future is invariably shadowed by the fear of repeating past mistakes, and in the case of the House of Atreus, the fear of divine retribution and the cycle of vengeance.

Through this interplay, Aeschylus invites reflection on the fragile nature of human hope, constantly threatened yet undeniably resilient in the face of fear.

Final Thoughts

“Agamemnon” is a powerful exploration of themes such as the cost of pride, the inescapability of fate, and the complex interplay between justice and revenge.

Aeschylus brings together personal tragedy and divine will, illustrating how the past inexorably shapes the present. The play’s tragic outcome serves as a poignant reminder of the destructive potential of unresolved grievances and the perilous nature of power and ambition.

Through its rich symbolism, compelling characters, and intricate plot, “Agamemnon” invites reflection on the enduring nature of these themes across centuries, maintaining its relevance and impact in the realm of classical literature.