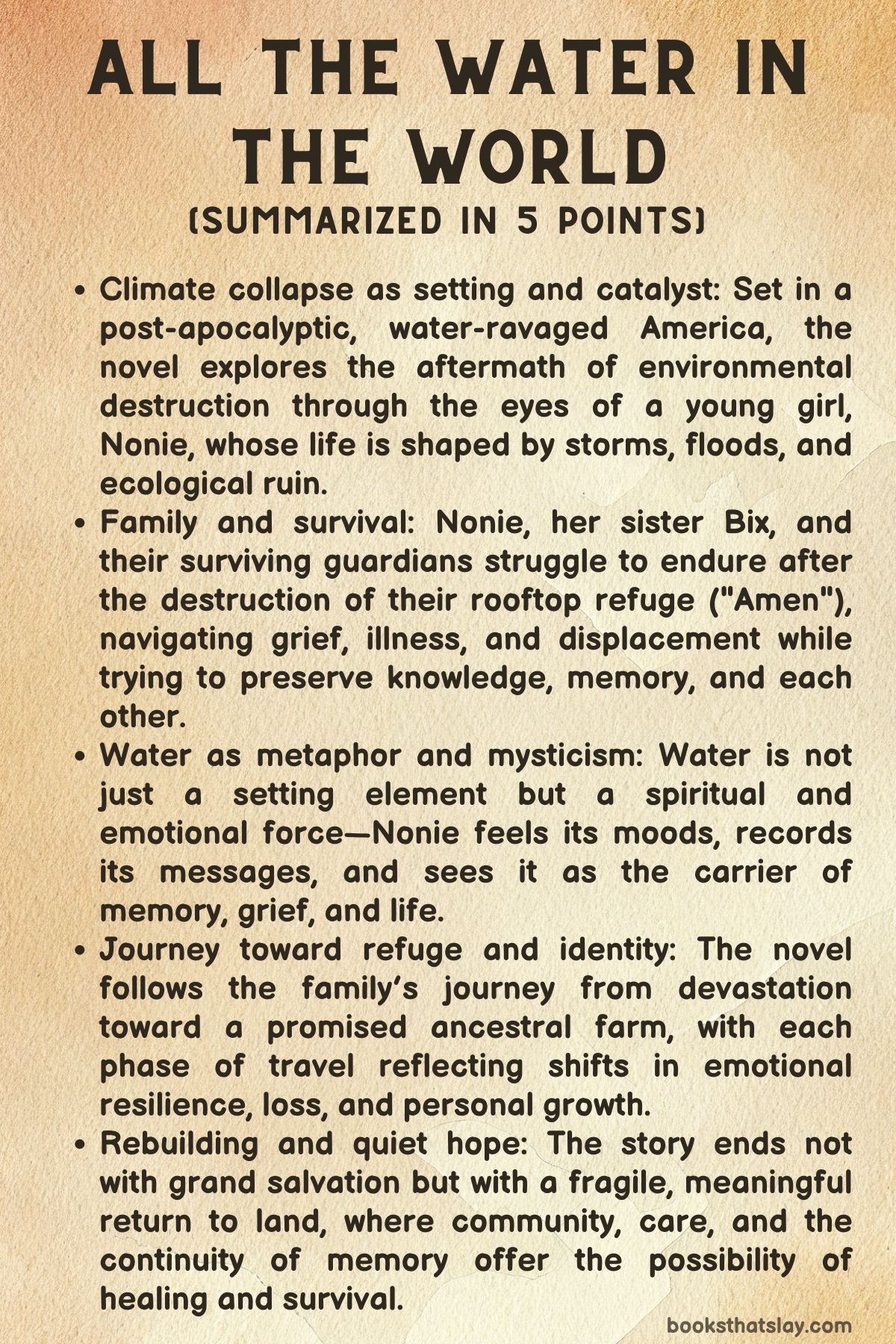

All the Water in the World Summary, Characters and Themes

All the Water in the World by Eiren Caffall is a haunting, poetic climate dystopia told through the eyes of a child navigating a flooded, collapsing America.

The book talks about Nonie, a young girl whose intimate connection with water becomes both her inheritance and burden. After environmental collapse submerges much of civilization, Nonie, her sister Bix, and their father set out across drowned cities, ruined museums, and ghostly homes in search of survival and meaning. With lyrical prose and fierce emotional clarity, Caffall fuses ecological grief with myth, memory, and resilience—creating a story that’s both an elegy and a beacon for a future shaped by water.

Summary

In a future reshaped by climate collapse, All the Water in the World unfolds through the voice of Nonie, a perceptive and spiritually attuned young girl living in a water-logged America.

The story begins in a ruined New York City, where Nonie and her family—sister Bix and their father—have found sanctuary atop the roof of the American Museum of Natural History.

Their community, called “Amen,” is a patchwork refuge built among the remnants of lost knowledge. Nonie keeps a Water Logbook, a hybrid journal and science notebook inspired by her late mother, a marine biologist who studied sea butterflies and believed in documenting life even as it drowned.

This fragile sanctuary is shattered when a hypercane, an unimaginable storm once only theoretical, arrives and devastates Amen.

Forced to flee with their friend Keller, the family descends into the drowned museum and retrieves an old birchbark canoe—an emergency escape tool and symbol of hope.

As the storm recedes, they embark on a perilous journey south through the submerged city, now an aquatic graveyard of cars, memories, and buildings turned into reefs.

As they paddle, the landscape—and their inner worlds—become increasingly surreal. Keller mourns his adopted son Mano, who died during an earlier flood.

Bix, who nearly drowned as a child, remains paralyzed by fear, while Nonie, drawn to water in ways she can’t fully explain, begins to emerge as a kind of intuitive guide.

Her bond with her mother’s memory, with water itself, becomes prophetic. The group presses forward, eventually leaving the city and moving through strange, drowned environments where ghost towns and derelict museums blur past and present.

Midway through their journey, the emotional and physical tolls mount. Nonie falls ill with fever, triggering dreams and visions that blur memory and mysticism.

They take refuge in an eerie house dubbed Feral House, filled with remnants of vanished lives. As they move forward again, symbols of decay and persistence—trees, birds, rivers—become spiritual companions.

Eventually, they find temporary safety in a mansion overlooking the Hudson River, run by two women, Alice and Esther, who embody two responses to grief: preservation and healing. Keller’s illness worsens here, Bix begins to take charge, and Nonie deepens her reflections on memory and legacy.

From this fog-wrapped refuge, they set out once more—this time headed to Hancock, where Nonie’s mother once lived.

The promise of “the farm” becomes a beacon for rebirth. When they arrive, the ancestral home is in ruins, but the well still pumps clean water—a miraculous sign of continuity.

The family settles in, joined by others like Esther and a man named Byron. They begin to rebuild, grow food, care for the sick, and nurture each other.

In the novel’s final chapters, Keller begins to heal. Bix finds new strength and marries Byron in a quiet ceremony, their union symbolizing personal and communal healing.

The farmhouse becomes a new version of Amen—less about holding on to the past and more about stewarding the future.

Nonie, having grown from a child into a chronicler and spiritual center, realizes that water is not only the source of their hardship but also the thread that binds them to each other, to memory, and to the earth.

The story closes with rain falling gently on the farm. Nonie, watching with quiet wonder, tells Bix to get inside. It’s a simple line—but it marks their arrival at something rare in this drowned world: shelter, belonging, and the beginning of something whole again.

Characters

Nonie

Nonie, the protagonist, is the heart of the novel. She is deeply connected to water, which becomes a central theme of the book.

Her emotional resilience is shaped by her complex relationship with water and the loss of her mother. Throughout the journey, Nonie serves as a spiritual and emotional anchor for the family, particularly in the absence of her mother’s guidance.

Her ability to read and feel the mood of the water mirrors her sensitivity to the emotional currents within her family. Her Water Logbook is not only a practical record of weather patterns but also a testament to her evolving understanding of survival, memory, and the continuity of life.

As the story progresses, Nonie matures from a child overwhelmed by loss into a young adult who accepts the cyclical nature of life and death. Water symbolizing both destruction and renewal is key to her character’s growth.

Bix

Bix, Nonie’s older sister, represents a more complex emotional trajectory. While Nonie’s connection to water is nurturing and intuitive, Bix’s experience is marked by trauma and fear.

Having nearly drowned in a previous flood, Bix has developed a deep-seated terror of water, which manifests as both psychological and physical paralysis. This fear shapes her character in ways that make her resistant to the world around her, yet over time, she begins to transform.

Her journey toward healing is gradual; she learns to confront her past trauma and emerge from it stronger. Bix’s eventual recovery and her capacity for love, particularly her relationship with Byron, highlight her character’s growth from fear and helplessness to strength and agency.

Father

The father figure in the novel is practical, protective, and determined. In the wake of the hypercane that devastates their home, he leads the family with a sense of urgency and purpose.

Always focused on the next step in their survival, his role in the family dynamic is that of a stabilizer, offering what little comfort he can in a world that seems bent on destroying everything they hold dear. However, the loss of his wife, and the burden of keeping his family together, weigh heavily on him.

Despite his stoic exterior, there are moments when his emotional vulnerability surfaces, especially in his interactions with Keller and the family’s struggle to preserve any sense of normalcy. His character provides a sense of continuity and pragmatism in the midst of chaos.

Keller

Keller, an adoptive father and figure of stability for the family, faces his own grief after the loss of Mano, his adopted son. This tragedy, coupled with the ongoing collapse of the world around them, causes Keller to experience deep emotional turmoil.

His grief is compounded by his growing physical decline, as illness gradually takes its toll on him. Keller’s character evolves from a source of support for the family to someone who must be supported himself, emphasizing the fragility of human life in the face of ecological collapse.

Despite his vulnerability, Keller’s love for Nonie and Bix, and his enduring presence as a caregiver, make him a vital emotional core in the story.

Alice and Esther

Alice and Esther are two important secondary characters introduced in the later stages of the novel. Alice, the owner of the mansion the family temporarily takes refuge in, represents a blend of grief and survival.

She is mourning the loss of her children to the collapse and has turned her mansion into a sanctuary for those who are also trying to survive. Her obsession with preservation, particularly the maintenance of the mansion as a shrine to the past, reflects a yearning to hold on to something that remains constant in a world of constant change.

Esther, on the other hand, is a healer who tends to Keller’s declining health. Her pragmatic approach to survival and her ability to offer physical care highlight the theme of resilience in the face of emotional and physical breakdowns.

Together, Alice and Esther embody the different ways people cope with the collapse—through preservation and practical healing, respectively.

Themes

The Fragility of Human Memory in the Wake of Ecological Disaster

All the Water in the World explores the fragility of human memory in the face of ecological collapse. As the world sinks into a chaotic and submerged state, memory itself becomes a precious commodity—one that is fiercely clung to and yet constantly threatened by the forces of destruction.

The family’s journey is not only a physical escape from the flooded world but also an emotional struggle to preserve the past in the face of overwhelming loss. The protagonist, Nonie, maintains a Water Logbook as a personal archive, documenting the changing states of water and its emotional resonance.

The Water Logbook also functions as a symbol of a larger struggle to hold onto the remnants of what was once a more stable world. Through this artifact, we understand that memory is not merely about preserving the past but about building a bridge between the lost world and the uncharted future.

As locations like the Museum of Natural History and the former refuge of Amen dissolve into ruin, the effort to safeguard knowledge takes on a spiritual dimension. Memory becomes both a survival tool and an act of defiance against erasure.

The Psychological Toll of Environmental Collapse and the Search for Resilience

The novel delves deeply into the psychological toll of living through a climate collapse, portraying how different characters cope with grief, trauma, and loss. Nonie and her family face a fragmented world that constantly shifts beneath their feet, causing emotional fractures that mirror the physical destruction of their surroundings.

Nonie’s unique relationship with water, especially her sensitivity to its moods, marks her as an intuitive observer of the psychological landscapes of those around her. Bix, on the other hand, struggles with a deep-seated fear of water, stemming from a traumatic near-drowning experience during earlier floods.

The novel explores how trauma does not merely shape one’s relationship with the natural world but also becomes an intrinsic part of one’s identity. Through Nonie’s eventual healing, and the family’s tentative rebuilding in Hancock, the narrative offers a subtle meditation on resilience—not as a return to normalcy, but as a deep acknowledgment of vulnerability and transformation.

The Sacredness of Water as Both a Literal and Metaphysical Element

Throughout the novel, water is portrayed not only as a vital and transformative physical force but also as a deeply sacred and metaphorical element that ties the characters’ lives together. Nonie’s connection to water extends beyond the practical necessity of survival—it becomes a portal to memory, spirituality, and personal transformation.

Water’s role is ever-present, from the flooded streets of Manhattan to the symbolic waters of the family’s farm, where a working pump becomes a sacred inheritance from her late mother. In one poignant moment, Nonie recognizes that water is the connective thread binding the past, present, and future, making it both a symbol of survival and an emblem of life itself.

The fluidity of water mirrors the transient nature of existence, where the physical and emotional states of the characters, like the rain itself, blur the lines between life and death, past and future. This concept is further amplified in the final moments of the story, where Nonie’s reflections on water underscore its metaphysical significance—not just as a literal substance, but as a conduit for memory, identity, and continuity in a world that has lost both its stability and its sanctity.

The Evolution of Family Dynamics Amidst Societal Collapse

As much as All the Water in the World is a story about survival in a collapsing world, it is equally about the evolution of family dynamics and the shifting roles within a fractured social structure. Nonie’s family is forced to constantly adapt as their environment changes, and in the process, their relationships transform.

Initially, Nonie’s father and Keller act as the primary protectors, but as Keller’s health deteriorates, Nonie steps into a more central role—acting as both the emotional heart of the family and a spiritual guide. Her interactions with her sister Bix evolve as well, with Bix’s trauma becoming a central tension in their relationship.

While Bix struggles with her fear of water, Nonie’s intuitive connection to it allows her to guide the family through physical and emotional waters. In contrast to the distant, almost mythic figure of their late mother, the family becomes a more democratic unit, where each member plays a vital role in their collective survival.

This transformation reflects a shift in the narrative focus from the external catastrophe to the internal, emotional landscape of the family. The novel showcases how love, grief, and memory continue to shape them even as their world dissolves.