All the Way to the River Summary and Analysis

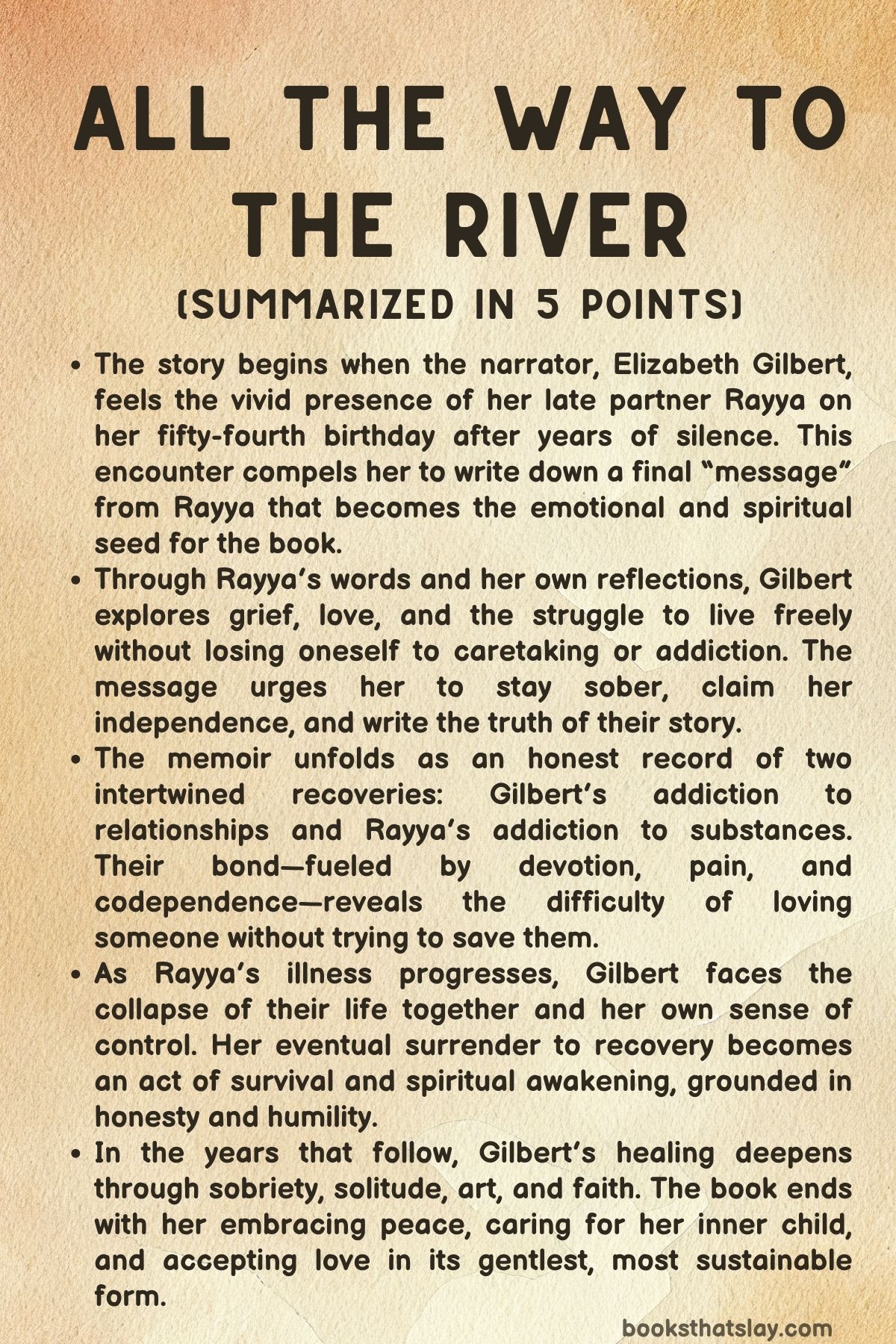

All the Way to the River by Elizabeth Gilbert is a reflective memoir that explores love, grief, addiction, and spiritual rebirth. The book revisits Gilbert’s life after the death of her partner, Rayya Elias, unraveling a story that examines not only loss but also the process of self-reclamation through sobriety and recovery.

Written in an intimate, confessional tone, the narrative moves between memory, prayer, and revelation. It captures Gilbert’s journey from emotional dependency to spiritual independence, tracing how the deep bond between two imperfect women—both artists and addicts—became both a crucible of pain and a catalyst for transformation.

Summary

The story begins on Gilbert’s fifty-fourth birthday in her New York apartment, where she suddenly feels the unmistakable presence of her late partner, Rayya Elias. Years after Rayya’s death, Gilbert had stopped sensing her spirit, assuming she had moved on.

But this morning is different—Rayya’s energy floods the room, and Gilbert feels compelled to write. In a torrent of dictated words, Rayya speaks through her, offering love, counsel, and closure.

She tells Gilbert that she no longer appears because Gilbert must walk her own path now. She congratulates her for staying sober and reminds her that they will meet “at the river” when it is time.

Then, just as abruptly as it began, the experience ends, leaving Gilbert in tears and peace.

From that moment, Gilbert decides to write the book Rayya urged her to create—a truthful account of their relationship, addiction, and recovery. She acknowledges it as her story alone, though Rayya’s spirit inspired it.

The memoir unfolds as an honest mosaic of letters, journal entries, poems, and recollections that chart their journey from friendship to love and finally to parting.

The narrative introduces Rayya: born in Aleppo, raised in Detroit, and defined by rebellion and resilience. She was a magnetic artist—musician, filmmaker, writer, and hairdresser—who battled addiction and self-destruction throughout her life.

She spent time in jail and rehab, lived homeless for stretches, and cycled through periods of recovery and relapse. Despite her chaos, Rayya radiated charisma and loyalty.

She met Gilbert in 2000, when the author came for a haircut, years before Eat Pray Love made her famous. Their connection was instant, though not romantic at first.

Over time, their friendship deepened into a profound companionship that defied boundaries of identity and convention.

Gilbert describes herself as a “sex and love addict,” driven by compulsive attachment and a need to be rescued by love. She explains how her addiction to emotional highs mirrored Rayya’s chemical dependency.

Where Rayya sought escape through drugs, Gilbert sought it through relationships. Both were governed by craving and fear of abandonment.

This honesty becomes a central theme: love as both salvation and sickness, and recovery as a long act of surrender.

When Gilbert divorced and found fame after Eat Pray Love, she experienced a strange imbalance between worldly success and emotional emptiness. Despite her wealth and independence, she continued to chase approval and belonging.

Her codependency manifested in what she calls “mania of generosity”—giving away money and care in attempts to earn love. Meanwhile, Rayya’s life was falling apart.

When she lost her home and health, Gilbert offered her refuge in a church she owned in New Jersey. This act of compassion also reignited their emotional dependency.

Rayya stayed nine years—years that transformed both their lives.

Their relationship blossomed fully after Rayya’s terminal cancer diagnosis. Confronted with mortality, they embraced their love openly and lived together as partners.

The initial months after diagnosis were marked by tenderness, creativity, and spiritual awareness. But as the illness progressed, reality grew darker.

The story moves into harrowing honesty about Rayya’s relapse into drug use as she sought relief from pain. What began as prescribed morphine escalated into methadone, fentanyl, and cocaine.

Soon, addiction returned with full force.

Gilbert portrays this descent without romanticizing it. Rayya became paranoid and volatile; Gilbert became consumed by caretaking and despair.

Their apartment turned into a battleground between life and death, sobriety and chaos. In moments of exhaustion, Gilbert even contemplated ending Rayya’s life to stop the suffering.

The impulse terrified her, and when Rayya, in a rare moment of clarity, accused her of “plotting,” Gilbert snapped out of the delusion. She fled the apartment and finally reached out to friends and sponsors for help.

They guided her toward recovery programs, urging her to detach from Rayya’s addiction before losing herself entirely.

An attempted intervention failed. Rayya rejected help and turned her pain against Gilbert, accusing her of betrayal.

Gilbert, broken and humiliated, left and stayed with friends. This separation marked the beginning of her own healing.

Though Rayya soon died, Gilbert’s collapse forced her to face the void she had always feared—life without someone to rescue or define her.

In the aftermath, Gilbert chose complete abstinence: no alcohol, no drugs, no romantic relationships, no distractions. She immersed herself in twelve-step programs, therapy, and prayer.

The emptiness was unbearable at first, but she began to sense a quiet divine presence offering comfort. She learned to distinguish between feeling “good” and feeling “well.” Her days became marked by routines—meetings, journaling, art, and meditation. Slowly, peace emerged where chaos had ruled.

She chronicled milestones of sobriety—thirty, sixty, ninety, and eventually three hundred sixty-five days—each marked by growth and humility. The pandemic years became her period of solitude and spiritual deepening.

She stopped drinking entirely, gave up psychedelics, and learned financial and emotional sobriety, ceasing her pattern of rescuing others. Through creativity—collage, drawing, writing—she found new joy in quiet creation.

Five years later, Gilbert reflected that recovery was not an event but a slow transformation. It took her multiple sponsors and years to finish the twelve steps.

Celibacy became a cornerstone of her strength, restoring her clarity and boundaries. She began to love her body and age without artifice, shaving her head and letting herself simply be.

When temptation reappeared in the form of a romantic invitation, she resisted, guided by an inner warning that reminded her of how easily she could relapse into old patterns. The incident reaffirmed her commitment to sobriety and self-trust.

In prayer, she redefines addiction as “misplaced worship”—the human urge to seek God in lovers, substances, or control instead of within. She thanks a patient divinity for waiting as she misdirected her love.

Finally, she meets her “inner child,” Lizzy, the vulnerable self she had spent a lifetime trying to protect through external validation. Learning to nurture this child becomes her truest recovery.

The story closes with serenity. Gilbert lives quietly in the New Jersey church she once shared with Rayya.

Her relationship with Rayya’s spirit feels lighter, based on peace rather than longing. She tends to her plants, writes, prays, and plans to adopt a small dog—a symbol of gentle companionship and self-care.

Her final act of love is toward herself and the small, enduring spark of life that remains curious and kind.

All the Way to the River ends not in reunion but in acceptance. Gilbert fulfills Rayya’s last instruction—to live her own life, sober, free, and awake.

The river remains the meeting place, but until then, she walks its edge, whole at last.

Key People

Elizabeth Gilbert

Elizabeth Gilbert, the narrator of All the Way to the River, stands as both the heart and the mirror of the story—a woman whose journey through love, addiction, grief, and self-recovery unfolds with raw self-awareness and humility. As a celebrated author, she begins as someone whose outer success hides deep inner chaos: her relationships are compulsive, her need for validation unrelenting, and her emotional dependence often disguised as generosity.

Lizzy’s self-identification as a “sex and love addict” reveals her primary struggle—not with substances, but with people. Her compulsion to merge, to rescue, and to be chosen is an attempt to fill an old void born of abandonment and fear.

Through her relationship with Rayya, this addiction becomes most visible. Her devotion morphs into codependency; her love, though genuine, becomes entangled with control and fear.

She sacrifices her boundaries, finances, and emotional health, believing she can save Rayya through caretaking. Yet in this suffering, Lizzy’s transformation begins.

Hitting emotional rock bottom forces her to seek recovery, where she learns to detach from others’ pain, to care for her “inner child,” and to redefine love as an act of presence rather than rescue. In the later sections, Lizzy emerges not as a saint or a martyr, but as a woman reborn in sobriety—disciplined, spiritually anchored, and finally capable of solitude.

Her decision to remain celibate, to stop seeking salvation in romance, and to nurture her inner world marks her as a figure of redemption and mature self-acceptance.

Rayya Elias

Rayya Elias, the muse, partner, and haunting spirit of All the Way to the River, is rendered with both ferocity and tenderness. Born in Aleppo and raised in Detroit, she carries within her the complexity of displacement—a woman of multiple identities: queer, immigrant, artist, and addict.

Her personality is magnetic, rebellious, and authentic to the point of danger. Rayya’s artistry flows across mediums—music, film, and writing—but so too does her self-destructive streak.

She identifies herself with the raw honesty of “ex-junkie, ex-felon, postpunk, glamour-butch dyke,” embracing contradictions as badges of survival.

Her addiction to drugs is not merely chemical but existential; it stems from an inability to bear the weight of her own brilliance and pain. Even in moments of clarity and love, she resists authority—including that of recovery itself.

She’s fiercely loyal to others yet sabotages her own chances at peace, living perpetually on the edge between transcendence and ruin. Her final relapse during illness is devastating not only because it hastens her death, but because it forces Lizzy to confront the limits of love and control.

Yet in death, Rayya becomes a spiritual teacher—her posthumous “voice” guiding Lizzy toward sobriety and freedom. The title’s river symbolizes her passage, her transformation from flesh to spirit, and her continuing role as both memory and mentor in Lizzy’s evolution.

God / Divine Voice

The divine voice that appears throughout All the Way to the River functions as both character and conscience. It embodies a patient, loving, and nonjudgmental presence that Lizzy experiences during her moments of despair and surrender.

Unlike the punishing deity of religious dogma, this God speaks in intimacy and humor, urging Lizzy to “put everything on the fire” and trust in the process of pain as purification. The divine voice contrasts sharply with the chaos of addiction; it offers stillness amid noise, clarity amid obsession.

This presence becomes Lizzy’s constant companion as she distances herself from her earthly dependencies. When Rayya’s voice fades, God’s becomes more audible—a symbolic exchange between human love and divine love.

The voice teaches her that true intimacy arises not from merging with others, but from merging with truth. In many ways, God in this book is Lizzy’s recovered inner voice—her higher self emerging from beneath the rubble of need.

The Inner Child (Lizzy)

The “inner child,” whom Lizzy eventually names “Lizzy,” is a vital psychological and spiritual figure in All the Way to the River. She represents the wounded innocence that has long driven Lizzy’s addictions—the part of her that fears abandonment and seeks love through others.

Initially, the adult Lizzy resents this child, seeing her vulnerability as weakness. But as she advances in recovery, she realizes that this inner child is not her burden but her salvation—the wellspring of her creativity, joy, and authenticity.

Caring for Lizzy becomes an act of self-reclamation. Through gentle daily rituals—drawing, poetry, and solitude—the narrator learns to mother herself, breaking the lifelong pattern of outsourcing emotional safety to lovers or caretakers.

The inner child, once neglected, becomes her companion and co-creator, guiding her toward wholeness. By the book’s end, when she plans to adopt a small dog “for them to love and learn to care for together,” it’s clear that her healing is not about renouncing love but about learning to give it without losing herself.

Themes

Grief and Connection Beyond Death

Grief in All the Way to the River functions as both a private ache and a profound spiritual channel. The narrator’s continued bond with Rayya, even years after her passing, challenges the idea that death severs relationships.

Instead, the novel treats grief as an evolving state of consciousness—one that allows communication and healing across dimensions of existence. The appearance of Rayya’s presence in the narrator’s apartment on her birthday represents a reawakening of unfinished emotional dialogue rather than a supernatural event.

Through this encounter, grief transforms from paralysis into expression, becoming a creative force that urges the narrator to write and to live truthfully. The river, a metaphor for death and passage, encapsulates this liminal space where the living and the dead meet not in body but in memory and meaning.

The narrator’s acceptance of Rayya’s continued absence signals not detachment but evolution—a realization that love can survive transmutation. Gilbert’s portrayal of grief is unsentimental; it acknowledges madness, exhaustion, and longing, yet also reveals how mourning becomes a form of spiritual apprenticeship.

It teaches the narrator endurance, humility, and self-compassion. The final acceptance that Rayya no longer needs to “come around” signals that healing lies not in holding on but in integrating loss into one’s daily life.

Grief, in this story, becomes less about clinging to what was and more about learning to exist within the quiet, sacred continuation of love that survives death’s interruption.

Addiction and Recovery

Addiction pervades every relationship and revelation in All the Way to the River, functioning as both a destructive compulsion and a mirror of human longing. Gilbert broadens the definition of addiction beyond substances, depicting it as any mechanism used to escape reality or fill emotional voids.

Rayya’s dependence on drugs parallels the narrator’s process addiction—her obsessive attachment to people and her need for validation. Both women are trapped in cycles of craving, withdrawal, and despair, yet their addictions spring from a shared hunger for safety and belonging.

The book refuses moral hierarchies between substances and emotions, portraying both forms of dependence as symptoms of spiritual disconnection. Recovery, therefore, is not presented as mere abstinence but as radical honesty and surrender.

The narrator’s sobriety unfolds as a process of rebuilding identity stripped of external affirmations. Meetings, routines, and solitude replace chaos, allowing her to confront the raw fear beneath her behaviors.

Gilbert’s treatment of addiction resists the cliché of redemption; instead, it emphasizes endurance, humility, and the slow, uncomfortable repair of the self. By calling addiction “misplaced worship,” she frames it as a spiritual distortion—an attempt to find transcendence in human relationships, substances, or control.

Recovery, conversely, becomes an act of devotion redirected toward life itself. In acknowledging that she and Rayya shared the same disease in different forms, the narrator transforms shame into empathy, suggesting that healing arises from recognition, not denial, of shared human weakness.

Love, Codependency, and Autonomy

Love in All the Way to the River is a site of both salvation and self-erasure. The narrator’s pattern of losing herself within relationships exposes how affection can mutate into dependence when rooted in fear rather than freedom.

Her lifelong compulsion to rescue others—offering homes, money, or emotional caretaking—reveals a deeper need to secure love by making herself indispensable. Rayya, as both lover and patient, becomes the ultimate projection of that impulse.

Their relationship, initially radiant and creative, deteriorates as illness and addiction consume them, turning love into obligation and desperation. Yet Gilbert’s insight lies in showing that codependency is not simply weakness but misplaced tenderness—the desire to merge completely with another in the hope of healing one’s own inner child.

Through recovery, the narrator learns that genuine love cannot coexist with control or sacrifice of self. Autonomy emerges not through detachment but through the reclamation of boundaries and self-respect.

By caring for her “inner Lizzy,” she redefines love as stewardship rather than salvation. The book’s emotional climax occurs not in reunion but in separation—the moment she recognizes that walking Rayya “to the river” means knowing where her responsibility ends.

Love, once conflated with martyrdom, becomes an act of truth: staying present without losing oneself, giving without collapsing.

Spiritual Transformation and the Voice of God

Spiritual awakening in All the Way to the River arises not from enlightenment but from collapse. When the narrator reaches the threshold of despair—considering mercy killing and suicide—divine guidance enters as a quiet, practical voice offering presence rather than rescue.

Gilbert treats spirituality as experiential rather than doctrinal: a series of dialogues between human fragility and a patient, forgiving consciousness. God’s voice is neither mystical nor distant but conversational, guiding her to sobriety, discipline, and creative integrity.

Through faith, the narrator reorients her life from chaos toward service, learning that divinity reveals itself most clearly in ordinary acts—drawing, writing, cooking, sitting in silence. The progression from belief to trust marks a deep inner transformation; she stops negotiating with God and begins cooperating with life as it unfolds.

The spiritual journey mirrors the river’s metaphor—flowing toward surrender, not control. This faith allows her to reinterpret suffering as instruction rather than punishment.

The story thus reframes spirituality not as escape but as engagement with reality’s fullness, including its pain. The voice of God ultimately replaces the voice of addiction, becoming the new internal rhythm through which she measures her actions and her peace.

Creativity, Truth, and Healing Through Art

Art in All the Way to the River functions as both confession and resurrection. Writing becomes the narrator’s method of survival—the only way to convert chaos into coherence.

The act of recording Rayya’s message, creating collages, and composing poetry turns private anguish into communal offering. Gilbert suggests that creativity and recovery share the same principle: rigorous honesty.

To write truthfully about addiction, love, and death, the narrator must relinquish performance and sentimentality, exposing her own complicity in pain. This creative integrity becomes spiritual discipline; the pen replaces the bottle, the page replaces the partner as a space of transformation.

Through art, she learns to hold contradictions—to mourn and celebrate, to confess and forgive—without seeking resolution. The book itself becomes the fulfillment of Rayya’s final instruction: to write something brutally honest and healing.

By turning suffering into art, the narrator not only memorializes Rayya but also reclaims authorship of her own story. Creativity thus becomes the bridge between grief and grace, the tangible form of the river’s flow.

Through sustained creative practice, the narrator achieves not closure but continuity—the understanding that art, like love, does not end; it simply changes the way we remain alive.