Anywhere with You Summary, Characters and Themes

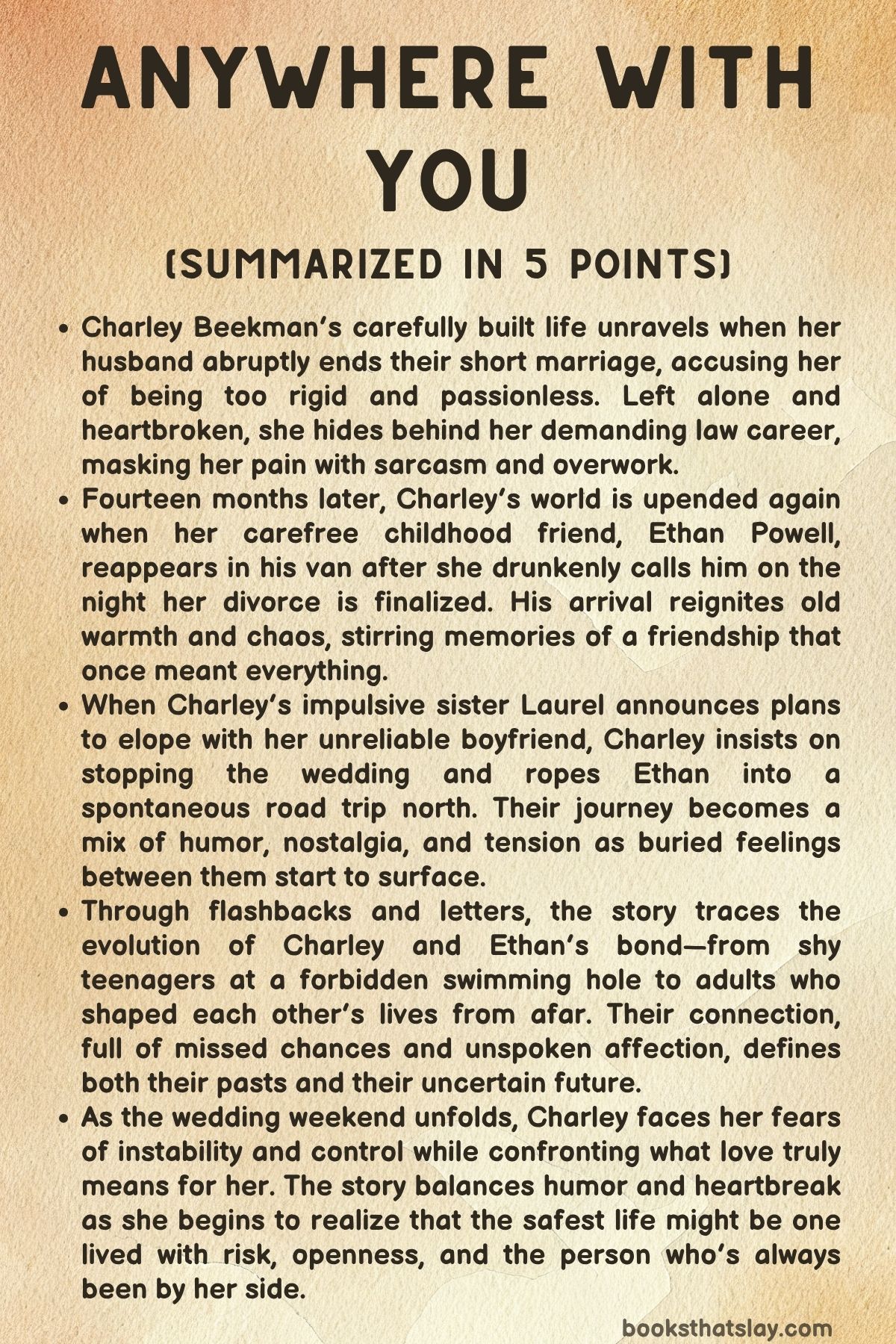

Anywhere with You by Ellie Palmer follows Charley Beekman, a woman whose neatly planned life unravels when her husband abruptly ends their marriage, forcing her to confront the fragility of her choices. Set between Minneapolis offices, small-town Minnesota lakes, and the open road, the novel traces Charley’s emotional journey from heartbreak and control toward rediscovery and love.

At its heart is her enduring connection with Ethan Powell, her childhood friend and lifelong almost-love. Through humor, vulnerability, and messy honesty, Palmer explores how people rebuild themselves after loss and how love can endure, reshape, and finally find its moment.

Summary

Charley Beekman’s story begins at the sudden end of her marriage. Her husband, Rich, announces his departure under the guise of “following the current of life,” leaving Charley stunned and humiliated amid their half-watched movie night.

He blames her guarded nature and devotion to work, accusing her of choosing her law career over passion. When he leaves, taking trivial items and their shared stability, Charley’s final thought recalls the words of her old friend Ethan Powell—a reminder of a truth she had long avoided.

Fourteen months later, Charley is still reeling from the divorce. A fourth-year associate at a Minneapolis law firm, she hides exhaustion behind sarcasm and expensive handbags she can’t afford.

Her coworker Stacy reminds her that it’s “divorce day”—the official finalization of her split—and hands her an expired steakhouse gift card as a joke. Charley later uses it to dine alone, toasting her failed marriage with too many drinks.

She wakes the next morning hungover and disoriented, only to find Ethan, her old best friend and longtime almost-lover, sleeping in a van outside her house. It turns out she drunkenly texted him the night before, prompting him to show up unannounced.

Though mortified, she’s secretly relieved.

Their reunion is awkward yet comforting. Ethan, still the charming, easygoing musician she remembers, makes breakfast while teasing her about her lawyerly tendencies.

Beneath their laughter lies an old tension—familiarity edged with unspoken attraction. When Charley’s sister, Laurel, calls to announce she’s impulsively gotten engaged to her on-again-off-again boyfriend Petey, Charley panics.

Determined to prevent her sister from repeating her mistakes, she decides to drive north to stop the wedding. Ethan offers to come along, transforming her desperate errand into an impromptu road trip.

The journey north revives old rhythms between them. Charley, anxious and overplanned, obsesses over logistics; Ethan counters with humor and calm.

At a gas stop, he soothes her stress with chocolate, recalling their years of friendship and shared history. When she learns her ex-husband is already engaged, she spirals into sickness, prompting Ethan to care for her at a truck-stop shower.

The scene exposes their intimacy and lingering chemistry, veiled behind banter but undeniable. Their dynamic oscillates between teasing comfort and emotional vulnerability as they navigate physical and emotional messes alike.

Interspersed letters and memories reveal their bond’s origins. As teens in Lewellen, Minnesota, Charley was the cautious observer behind her father’s camera, and Ethan was the kind boy who stayed behind when others jumped into forbidden lakes.

Their friendship deepened through years of distance and correspondence—letters full of humor, shared dreams, and quiet longing. Ethan pursued music with his band Lemonface, while Charley chose law, both driven by the need for meaning but in opposite ways: he chased freedom, she sought control.

A flashback to college shows the pivotal moment when unspoken affection almost became love. After a gig, they drive together, arguing and laughing until Ethan blurts that he finds her beautiful.

The moment is interrupted by circumstance and her distraction with another boy. Their feelings retreat underground, shaping the years of friendship and missed chances that follow.

Back in the present, the road trip leads them to Wet Ted’s Canoe Outfitters—a rustic outpost where they rent gear for the final leg to Laurel’s campsite wedding. Ted flirts shamelessly with Charley, and Ethan’s jealousy surfaces despite his attempts to hide it.

During their canoe trip through the lakes, memories resurface, and tension builds. When Ethan dares Charley to jump off a cliff into the lake, she hesitates but ultimately trusts him.

They leap together, surfacing breathless and laughing, and finally share the long-delayed kiss that shifts everything between them. The moment is intense and overdue, but before it can go further, a stranger interrupts, sending them back into reality.

At the campsite, they find Laurel and Petey surrounded by friends—Harlow, Walter, and Jonah, the officiant. The group’s energy is chaotic and celebratory.

Charley struggles between supporting her sister and fearing she’s making a mistake. Meanwhile, Ethan’s tenderness toward her grows, even as both pretend their kiss was impulsive.

A phone call from Charley’s overbearing boss interrupts the festivities, but for once, she stands her ground and hangs up, reclaiming a piece of her independence. Her sister’s wedding plans, however, start to unravel when the officiant falls ill.

Despite the delay, Laurel insists the ceremony will go on.

A night of drinking and laughter follows. Laurel’s friends drag everyone to a dive bar where Ted reappears—now revealed to be ordained and willing to officiate.

During a toast, Ethan’s heartfelt speech about love and connection strikes Charley deeply; his words feel like a message meant for her. As the evening dissolves into Laurel’s wild antics, including an impromptu streaking dare, Charley finally lets herself laugh freely, feeling a release she hasn’t known in years.

But soon after, reality intrudes again. Charley and Ethan argue over their undefined relationship.

He confesses that he’s loved her for years, that he couldn’t attend her wedding because watching her marry another man would have broken him. She accuses him of abandoning her, and he counters that he couldn’t bear to interfere when she seemed happy.

He came back when he learned her divorce was final, ready to start over. Yet Charley, fearful and self-protective, pushes him away.

She insists he would tire of stability and that she’d only hold him back. Their fight ends in heartbreak, with a final kiss and his quiet departure.

In the aftermath, Charley sinks into work and loneliness until Laurel and Petey show up, breaking into her house to check on her. Through her sister’s blunt compassion, Charley realizes her fear of being left has driven her to build walls against the one person who’s always returned.

She learns Ethan is selling his van and planning a new life, and it jolts her into clarity. She decides safety without love isn’t real stability.

A week later, Charley surprises Ethan at Wet Ted’s. Nervous but determined, she confesses everything she had withheld: that she quit her job, sold her house, and bought his van under an alias.

She wants to build a shared life that isn’t about compromise but creation—travel, work, and love on their own terms. Ethan, moved, simply says “okay” and takes her hands.

Together, they officiate Laurel and Petey’s elopement at the lakeside waterfall, with Charley performing the ceremony herself. As dusk falls, Ethan reveals he already knew her plans—Laurel had told him—but wanted her to say the words herself.

They kiss and agree to try, not as a fantasy but as a choice.

In the epilogue, two years later, Charley and Ethan live by Lake Lewellen with a rescued cat named Cat Power. Van life gave way to a lakeside townhouse and part-time travel.

Ethan writes music; Charley practices flexible law and pursues photography. Their lives are imperfect but shared, grounded in both adventure and peace.

On the dock, Ethan kneels with an emerald ring, proposing with awkward sweetness. Charley says yes, joking they should get “married married” for real this time.

They kiss as the lake glows at sunset—choosing, at last, to live anywhere together.

Characters

Charley “Chuck” Beekman

Charley is the novel’s gravitational center, a fourth-year associate whose instinct for structure is both armor and limitation. Early abandonment patterns and a restless childhood tune her toward stability, so she chases orderly institutions—marriage, corporate law, a house—hoping permanence will quiet uncertainty.

When Rich leaves, that scaffolding collapses and exposes her deeper fear: that love is contingent and she is fundamentally “too much” or “not enough. ” The road trip with Ethan forces her to test control against vulnerability; humiliations like the truck-stop shower and spontaneous leaps into cold water become rites of unguardedness.

Her wit is defensive until she slowly learns to use honesty instead of sarcasm, culminating in the choice to sell the house, quit the job, and design a portable life on her own terms. Charley’s arc reframes competence from rigidity into agency: she stops managing catastrophe and starts authoring joy.

Ethan Powell

Ethan embodies motion—van life, music, improvisation—yet he is not careless; his looseness is a philosophy of presence shaped by small-town ceilings and deferred dreams. His love for Charley precedes language and outlasts failed timing, but his historical pattern of yielding to her choices reads, to her, like disappearance.

The novel complicates the trope of the feckless artist by making Ethan unusually steadfast in crisis, the person who holds hair back, cooks breakfast, and tells difficult truths. His confession that he skipped her wedding because he loved her is the emotional fulcrum: not a grand gesture so much as an admission of long endurance.

By the end he chooses rootedness not as a capitulation but as a new canvas—music from home, travel by season—proving that commitment can enlarge freedom rather than constrict it.

Laurel Beekman

Laurel is Charley’s radiant foil: impulsive, unembarrassable, allergic to hesitation. She proposes first, elopes in the woods, and speaks in the vocabulary of plunge rather than plan.

Yet beneath the glitter of recklessness is a woman who has learned to forgive herself and to define real love against the chaos of their parents’ on-again, off-again marriage. Laurel’s loud loyalty drags Charley out of self-punishing isolation, and her refusal to be lost in Charley’s shadow restores sisterhood as a space of mutual permission.

Her arc clarifies that spontaneity can be a discipline of trust, not a symptom of instability.

Petey

Petey begins as the hometown constant—hockey, campsite rituals, the familiar gravity of a boy who never entirely left the lakes. His bond with Laurel stretches across adolescence, mistakes, and reconciliations, making their elopement feel less like caprice than culmination.

Petey’s steadiness anchors Laurel’s leaps and mirrors Ethan’s role for Charley; he demonstrates that endurance can be romantic, and that humble commitments—showing up, setting the fire, carrying the canoe—are their own epic.

Rich

Rich functions as the catalyst rather than the destination. His self-help rhetoric and envy of Charley’s work ethic refract a deeper insecurity: he wants the glow of spontaneity without the labor of intimacy.

By calling the marriage roommate-ship, he reveals a transactional understanding of passion that withers when maintenance is required. His quick engagement after the divorce underscores the hollowness of his quest, and his departure—petty theft of a charger and all—ironically frees Charley to interrogate what a chosen life, not a prescribed one, could be.

Ted (“Wet Ted”)

Ted is the mythic local—competent, wry, a little too handsome—who sells gear, officiates weddings, and unintentionally stokes Ethan’s jealousy. He represents the seductive ease of a different path: flirtation without history, a life organized around water and weather.

In narrative terms he’s a pressure test; Charley’s clear choice not to drift toward him confirms that her desire is not for novelty but for an old truth finally spoken aloud.

Harlow

Harlow’s charisma and camera supply both levity and witness. As a photographer who sees people kindly, she midwifes several turning points: bachelorette mischief that loosens Charley’s grip, candid observations that nudge Ethan to name what he wants, images that fix fleeting courage into memory.

Harlow models creative adulthood without martyrdom—work as play, art as companionship—and offers Charley a template for post-firm professional joy.

Walter

Walter is a cautionary echo of corporate burnout, a man whose spreadsheets no longer translate into meaning. He is generous, game for lake antics, and quietly hollowed out, reminding Charley what her current trajectory threatens to make permanent.

His presence sharpens the novel’s critique of prestige without purpose and helps justify Charley’s radical course correction.

Jonah

Jonah, the accidental officiant and enthusiastic joiner, embodies community improvisation—the way strangers can become necessary for a day. He arrives as comic interruption and exits as ritual facilitator, proving that found family is built from whoever is willing to carry the next task with heart.

Stacy

Stacy’s relentless pep and office gossip mask a shrewd read on Charley’s exhaustion. She is the kind of workplace friend who presses a silly gift card into a trembling hand, making survival feel a little more possible.

Stacy keeps the novel honest about how small kindnesses prop up people trapped in large systems.

Bob

Bob is the voice of the firm in a single, insistent register: availability equals value. His weekend call and Charley’s refusal supply one of the book’s most satisfying boundaries.

Bob is not villainous so much as emblematic; he personifies a machine that runs on other people’s forfeited weekends, and the moment Charley hangs up, the plot begins to breathe.

Owen Twombley

Owen is the college crush whose texts arrive like confetti at precisely the wrong time. He represents the safe fantasy—a curated partner who matches résumé lines and predicts a certain life.

His role in the past clarifies why Charley initially mistakes compatibility for destiny and why Ethan’s messier, riskier attention feels dangerous but true.

Margot

Margot, the offstage girlfriend Ethan leaves before Charley’s wedding, is the cost of his delayed honesty. Her absence haunts his guilt and complicates his declaration, reminding the reader that romantic clarity arrived late and that someone else bore that lateness.

Through Margot, the book refuses to varnish the consequences of almosts.

Themes

Friendship’s Long Arc into Love

Years of shared jokes, letters, and roadside rescues set a groundwork that reshapes what romance looks like for Charley and Ethan. Their bond is not a sudden spark but a compounding of small, steady moments that keep proving the same point: intimacy is built in the ordinary as much as the dramatic.

The snapshots from adolescence—the waterfall afternoon, the mailed chocolates during exams, the back-and-forth about careers—create a living archive where both learn how the other thinks, so that comfort and chemistry arrive in the same breath. This history changes the stakes of every later scene.

A first kiss by the lake arrives not as a novelty but as a recognition; the charged silence in a truck-stop bathroom matters because there is a decade of trust behind it. Even their worst fights carry an undercurrent of care, which is why arguments can turn on a single memory or misread confession.

The novel uses delayed timing—missed moments at the bachelorette party, the near-confession on Pothole Alley—to show that desire without readiness often becomes hurt, and that love demands more than longing: it asks for clarity, courage, and sustained presence. By the time Charley buys Ethan’s van and proposes a life built for both of them, friendship has already taught them the necessary muscles of apology, patience, and daily attention.

The love story in Anywhere with You insists that romance grounded in friendship is not less passionate; it is simply better at surviving stress tests, because the proof of devotion has been accumulating for years in acts of reliability.

Stability, Freedom, and the Cost of Control

Order is Charley’s first language. A patent-law career, a tidy home, color-coded errands, even the defensive joke about becoming a “bed person” with a bar cart—these are strategies aimed at safety after a childhood marked by parental inconsistency.

Ethan’s van, touring gigs, and side work rebuilding campers represent the other pole: movement as a philosophy. The narrative places these value systems in the same canoe, sometimes literally, and watches what happens when they try to steer together.

Rich’s abandonment at the beginning is not only a breakup but a critique of Charley’s alleged guardedness; his rhetoric turns spontaneity into a moral high ground. The story refuses that frame.

It shows how performative impulsiveness can mask selfishness just as overplanning can mask fear. Through the road trip, the campsite delays, and the forced pauses—dead phones, long drives, broken schedules—Charley learns that control often fails where care succeeds.

She can engineer outcomes at work, but relationships resist project management. Meanwhile Ethan’s freedom is tested against responsibility: he confesses jealousy, shows up for difficult conversations, and cancels shows to be present when it counts.

What emerges is not a winner between stability and freedom but a third option: structure that flexes. Charley quits a job that keeps her in chronic flight-or-fight and becomes counsel on her terms; Ethan anchors in a home base while keeping room for travel and music.

Their compromise is not about splitting the difference; it is about choosing the conditions under which each can stay fully themselves without asking the other to disappear. The result models a partnership that prizes reliability without rigidity and adventure without abandonment.

Divorce, Shame, and Rewriting the Self

The early montage on Charley’s phone—“Building a Home Together”—is a knife disguised as nostalgia. The images are not just memories; they are exhibits in a trial she keeps running against herself.

Rich frames the split as a deficit of passion and spontaneity, language that tempts Charley to accept blame as identity. The novel maps the slow unlearning of that shame.

Public rituals become private humiliations: drinking alone at Ruth’s Chris, waking with “WET TED” on her hand, vomiting in the van. Instead of treating these as comic beats only, the story uses them to trace how dignity is rebuilt.

Ethan’s care in unflattering moments is a counter-argument to the idea that Charley is lovable only when polished. The legal world amplifies the theme: she negotiates other people’s conflicts for a living while postponing the hardest conversation with herself—what she actually wants beyond a résumé that proves she is safe.

Divorce law turns promises into inventory; Charley learns that worth cannot be itemized. The shift comes when she stops defending the life she once curated and starts choosing one she can inhabit without bracing.

Selling the house is not a rejection of stability but of a museum of expectations. Even the bachelorette-party straw functions as a reclaimed token; it once symbolized a past she was running from, and later becomes proof of a deeper loyalty she refused to name.

By the epilogue, remarriage is not a redo but a renaming: a woman who once measured success by containment now measures it by alignment. Anywhere with You treats divorce not as failure’s final form but as a hard education that teaches better questions about love, work, and home.

Sisters, Mirror Lives, and the Education of Care

Laurel’s whirlwind engagement to Petey is not a subplot for chaos; it is a mirror that forces Charley to examine her own defaults. Laurel is the family’s accelerant—irreverent, loud, reckless in Charley’s eyes—and yet her relationship with Petey contains a quiet endurance that challenges Charley’s assumptions about “impulsive” love.

Their history stretches from adolescent flirting to adult commitment, and the decision to marry in the woods, officiated by an unlikely minister, interrogates the difference between speed and depth. The sisters argue as only siblings can, weaponizing old roles, but the late-night break-in and the waterfall elopement recast those roles.

Laurel is not simply careless; she is capable of tenderness and candor that Charley needs. She tells Charley that real love is not their parents’ erratic version, and she refuses the script where closeness means self-erasure.

In return, Charley learns to practice care that does not patronize—showing up, asking better questions, and trusting Laurel’s agency even while voicing concern. Petey’s steadiness matters here; the hockey kid becomes a man who wants the same girl he met years ago, not a fantasy of her.

Through this quartet—Charley, Laurel, Ethan, Petey—the book sketches a small community in which everyone’s courage teaches someone else how to live. The culminating gesture, where Charley becomes the officiant for Laurel and Petey, completes the lesson: sometimes loving a person means blessing a choice you did not design.

The sisters end up defining adulthood not as distance from family but as a recalibrated intimacy that allows difference without collapse, a model of loyalty that makes room for separate destinies under the same sky.

Timing, Honesty, and the Mess of Confession

Across the years, the right words often arrive at the wrong hour. Ethan says “I love you” into a rideshare window when Charley has trained herself to hear only friendly banter.

Charley answers major questions with career accomplishments because naming desire feels like handing over a weapon. Their dynamic demonstrates how fear edits language until it becomes noise.

The novel is full of near-misses: a kiss interrupted by a stranger on a trail, a roadside handhold broken by buzzing texts, a best-man invitation poisoned by unspoken longing. These misalignments are not mere plot devices; they show how timing is a moral problem as much as a logistical one.

Truth delivered too late can wound as sharply as deceit. When the driveway confrontation finally strips away euphemism—Ethan admitting the wedding-day no-show, Charley naming her terror of not being enough—their fight is brutal precisely because it is accurate.

Honesty, however, does not redeem itself without action. The story distinguishes confession from commitment.

Ethan’s feelings matter, but so do the miles he drives, the shows he cancels, the willingness to hear no. Charley’s admissions matter, but so do the job she quits, the house she sells, the van she buys.

By the time they agree to test a week on the road, their words have a chassis under them. In Anywhere with You, love matures when truth is spoken at a time and in a form that the other person can actually use.

The book argues that clarity is not a single speech but a pattern of choices that make future conversations easier rather than sharper.

Risk, Rituals, and the Objects That Hold a Life

Jumping from a cliff, stepping into a stranger’s shower stall, pulling a van onto an unmarked road—these are staged risks that rehearse a more serious decision: trusting another person without a backup plan. The novel pairs those leaps with rituals and talismans that store meaning.

Charley’s father’s camera turns observation into agency; when she photographs Ethan, she is not hiding from experience but claiming it, deciding what will count as real later. The goofy straw from the bachelorette party begins as a joke and becomes a portable archive of a feeling she refused to admit; when she finally explains why she kept it, the confession converts kitsch into evidence.

Even the expired steakhouse card and the “Sexy Mother Trucker” T-shirt participate in this logic—objects that could signal embarrassment are repurposed as markers of turning points. Risk here is not thrill-seeking; it is a disciplined exposure to uncertainty for the sake of alignment.

That is why the canoe scene matters: asking “Do you trust me? ” is not a dare so much as a contract.

The wedding in the woods operates as a counter-ritual to the earlier, misfitting ceremony Charley tried to endure with Rich; vows spoken beside water insist that commitment is a daily practice, not a performance for guests. Buying the van under an alias is both audacious and practical, a blueprint for avoiding the old trap where one partner relocates entirely into the other’s life.

By the epilogue, the renovated Rambler, the emerald ring, and the lakeside townhouse form a constellation of objects and places that record how risk, once guided by care, becomes tradition.

Work, Worth, and Redefining Success

Charley’s firm culture runs on exhaustion disguised as excellence. The emergency calls, the client fee squeeze, the boss who treats weekends as inventory—these grind her sense of self until productivity becomes the only story she can tell about her value.

The book stages a quiet rebellion against that script. The contrast with Ethan is not that artists are free and lawyers are trapped; Ethan faces his own treadmill—expectations around the family donut shop, the hustle of low-margin gigs, the nagging sense of being replaceable.

What shifts is the criterion by which choices are judged. When Charley begins to ask whether her work enlarges or reduces her, she starts making decisions that make room for the rest of her life: flexible counsel, selective clients, time for art that does not need an invoice to matter.

Ethan’s evolution mirrors this; success stops meaning constant motion and starts meaning sustainable creativity anchored in a real home. The narrative also dignifies competence.

Charley’s ability to solve problems—getting the car unstuck, steering emergencies, managing logistics—becomes an asset in love rather than a shield against it. The final balance is not anti-ambition; it is a different ambition, where thriving includes weekends that belong to you, projects you can stand behind, and relationships that do not sit at the mercy of your calendar.

Anywhere with You proposes that worth measured only by output invites relational poverty, and that a better metric is the capacity to keep promises to yourself and the people you choose. In that accounting, love and work can support each other instead of competing for the same scrap of energy.