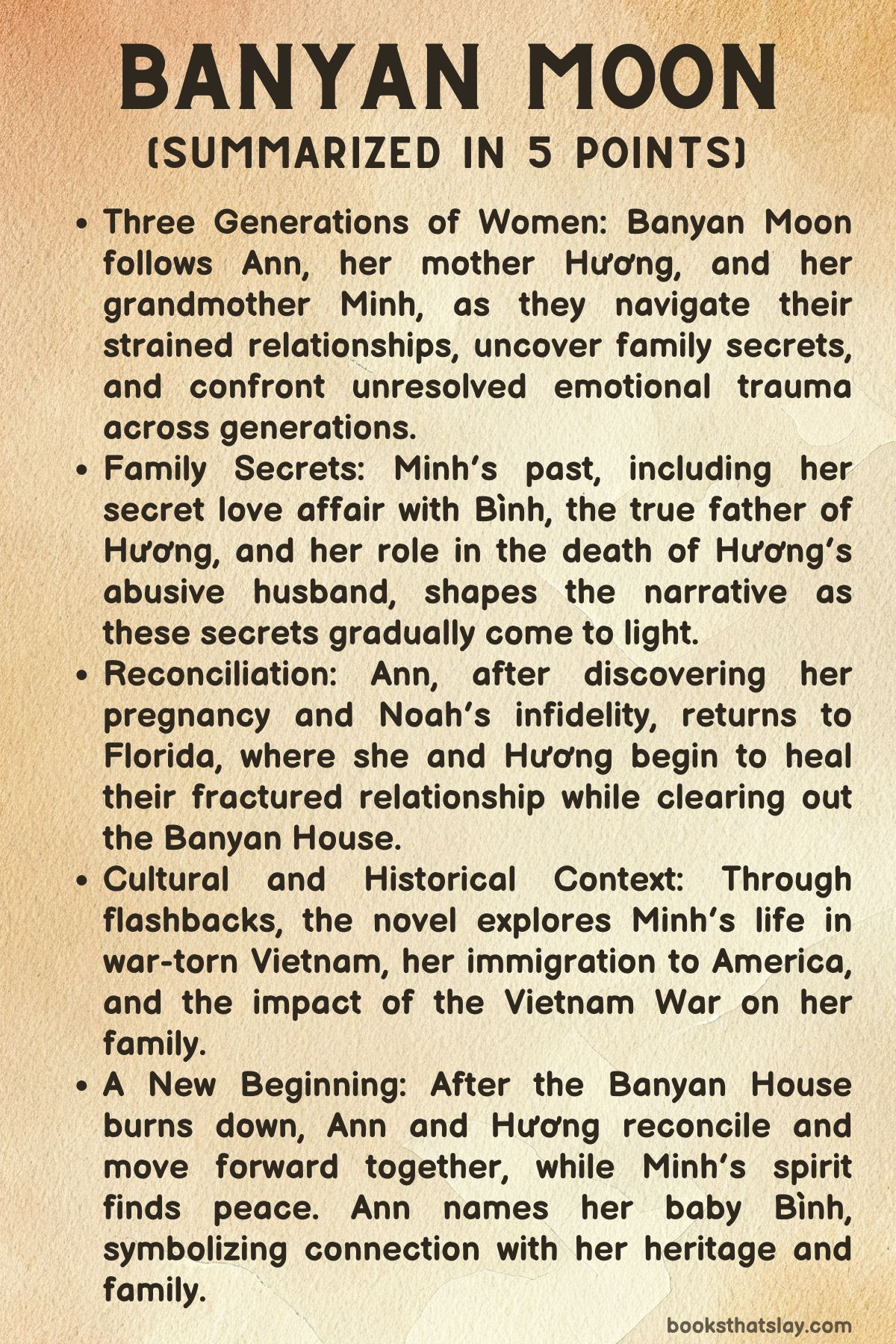

Banyan Moon Summary, Characters and Themes

Banyan Moon by Thao Thai is a poignant, multigenerational debut novel that explores themes of family, secrets, and reconciliation. Set between Vietnam and the United States, the story unfolds through the perspectives of three Vietnamese-American women—Ann, her mother Hương, and her grandmother Minh.

These women grapple with their individual traumas, long-buried secrets, and complex relationships with one another, all while sorting through the ruins of a decaying mansion known as the Banyan House. Thai’s evocative prose delves into identity, motherhood, and the impact of the past on future generations, offering readers a touching exploration of love and forgiveness.

Summary

In Banyan Moon, three generations of Vietnamese-American women—Ann, Hương, and Minh—navigate the complexities of their relationships while grappling with the weight of their pasts. Ann, in her late twenties, leads a seemingly stable life in Michigan with her wealthy boyfriend, Noah.

However, this stability is shattered when she discovers Noah has been unfaithful just as she learns she’s pregnant. Shortly after, she receives word that her grandmother, Minh, has passed away.

Feeling lost, Ann leaves Noah and returns to Florida to reunite with her estranged mother, Hương, as they begin the daunting task of sorting through Minh’s sprawling mansion, the Banyan House.

Minh, who narrates parts of the novel as a ghost observing her daughter and granddaughter, inherited the Banyan House from a former cleaning client, and the home has since been filled with memories and clutter. Ann hasn’t visited in years, having distanced herself from Hương due to their fraught relationship, but she was always close to her grandmother.

As Ann and Hương sort through the house’s contents, the tension between them is palpable. Both women harbor unspoken resentments: Hương feels the sting of her daughter’s absence, while Ann resents her mother’s rigid expectations.

Minh’s past comes to light as the story flashes back to her youth in Vietnam during the war. As a teenager, Minh fell in love with a boy named Bình and conceived a child out of wedlock—Hương. She married another man, Xuân, before Hương’s birth, and together they later had a son, Phước.

When Xuân died young, Minh immigrated to America with her children, never revealing to Hương that Bình was her biological father. Minh’s life was shaped by sacrifice and the haunting folktale of Chú Cuội, a man tied to a magical banyan tree.

As Ann and Hương sift through their family’s past, they begin to repair their strained bond. Ann eventually confides in her mother about her pregnancy, and they visit a Vietnamese temple for a blessing.

Despite Noah’s efforts to rekindle their relationship, Ann distances herself, reconnecting instead with her high school friend Crystal and her ex-boyfriend Wes. Meanwhile, Phước, Hương’s brother, becomes increasingly frustrated after learning that the Banyan House has been left to Ann and Hương.

He believes the house rightfully belongs to him and his family and attempts to manipulate Hương into giving it up.

Hương’s own backstory reveals a history of abuse at the hands of her husband, Vinh, whom she eventually fled with baby Ann.

In a shocking turn, it is revealed that Minh killed Vinh when he came to the Banyan House to harm Hương. This secret is one of many that has shaped the family’s troubled dynamics.

As the novel reaches its climax, a fire—possibly started by Phước—destroys the Banyan House, though Hương, Ann, and Noah escape unharmed. Minh’s spirit finally finds peace, reuniting with Xuân in the afterlife.

Ann and Hương, now closer than before, start fresh by moving into a cottage together. Ann names her newborn son Bình, honoring her family’s past, while she begins a new chapter in her life.

Characters

Ann

Ann is a complex character in her late twenties, navigating significant personal and emotional upheavals throughout the novel. She begins the story living with her wealthy boyfriend, Noah, and feeling disconnected from her mother, Hương.

Ann’s struggle with her identity is palpable as she faces the challenges of her heritage and her strained familial relationships. The revelation of her pregnancy marks a turning point in her life, catalyzing a series of decisions that ultimately lead her back to her roots, both physically and emotionally.

Her relationship with Noah begins to deteriorate after discovering his infidelity, reflecting her broader struggle with intimacy and trust. Ann’s return to Florida and the Banyan House signifies her desire to confront the unresolved tensions between her and her mother.

As she sorts through the house’s accumulated possessions, Ann is also sorting through her emotional baggage. Her relationship with her grandmother Minh, and her ultimate decision to burn the photograph that reveals Hương’s true parentage, showcase her protective nature and her attempt to shield her mother from pain.

By the end of the novel, Ann has matured significantly, forging a healthier relationship with Hương and making the decision to raise her son, Bình, with a stronger sense of independence and connection to her heritage.

Hương

Hương, in her early fifties, is a character defined by a history of trauma, resilience, and secrecy. Her relationship with Ann is fraught with tension from years of emotional distance and unspoken pain.

Much of Hương’s life has been shaped by her experiences as a young woman fleeing a toxic and abusive marriage, compounded by the murder of her husband, Vinh, and the concealment of this act from her daughter. Hương’s choice to raise Ann in the protective environment of the Banyan House, under the watchful care of her mother, Minh, is both a testament to her strength and an indicator of her unresolved grief.

Throughout the novel, Hương is forced to confront the ghosts of her past, both literal and metaphorical, as she deals with the death of her mother and the burden of long-kept secrets. Her desire for a nuclear family, despite the violence she endured, reflects her longing for stability, a dream that was shattered by her marriage to Vinh.

Hương’s inability to reveal the truth about Ann’s father and the murder of Vinh underscores the weight of silence in her life. Her growth, much like Ann’s, is gradual but significant, as she learns to reconnect with her daughter and embrace a future that is not defined by the past.

Minh

Minh, the matriarch of the family and one of the novel’s central narrators, provides a powerful connection between the generations. Her character is shaped by the experiences of migration, loss, and sacrifice.

Having fled Vietnam during the war with her two children, Hương and Phước, Minh represents the older generation’s struggle to adapt to life in America while carrying the emotional scars of the past. Her inheritance of the Banyan House, once a client’s home, is symbolic of her upward mobility but also of the burden she bears in preserving a legacy for her family.

Throughout the novel, Minh exists in a liminal space as a ghost, observing the tensions between her daughter and granddaughter while reflecting on her own life choices. The presence of the banyan tree outside the house and the folktale of Chú Cuội that she often told Hương speak to her deep connection to Vietnamese culture and the tension between holding on to the past and letting go.

Minh’s relationship with Xuân, her late husband, and her decision to never reveal Bình as Hương’s true father reflect the sacrifices she made to protect her children from emotional pain. Minh’s final act of moving on to reunite with Xuân in the afterlife symbolizes her acceptance of the past and her role in guiding Hương and Ann toward healing.

Phước

Phước is portrayed as an ambitious, often antagonistic character. His resentment toward Hương and Ann for inheriting the Banyan House speaks to his deep-seated feelings of entitlement and frustration.

As a man who desires success and prestige, he views the house as a symbol of his aspirations, one that he feels is unjustly denied to him. Phước’s anger and manipulation, particularly his attempts to persuade Hương to give up the house, underscore his desire for control and recognition.

His eventual role in the fire that consumes the Banyan House, while left somewhat ambiguous by Thai’s writing, reveals the destructive nature of his ambition. Despite his outwardly successful life with a wife and daughters, Phước’s internal conflict is driven by feelings of inadequacy and betrayal, especially when it comes to his mother’s decisions.

His character serves as a foil to the women in the novel, whose connections to the house are more emotional and rooted in history rather than material gain.

Noah

Noah’s character is primarily a representation of the affluent and emotionally distant life Ann initially leads. He is a wealthy man who, despite his outward charm, is revealed to be unfaithful and unreliable.

His relationship with Ann is built on a fragile foundation, and his infidelity serves as a catalyst for Ann’s journey of self-discovery. While Noah attempts to rekindle their relationship after learning about the pregnancy, his role in the novel is more symbolic of the life Ann chooses to leave behind.

His willingness to be involved in their son’s life, despite Ann’s rejection of him as a romantic partner, indicates that his character, while flawed, is not entirely unsympathetic. He represents the part of Ann’s life that she ultimately decides to move beyond, choosing independence and familial reconnection over the safety and security that Noah offers.

Wes

Wes, Ann’s high school boyfriend, plays a more understated but important role in Ann’s journey. His reappearance in her life allows Ann to explore the idea of rekindling old connections and confronting the person she used to be.

Wes is depicted as a kind and reliable figure, in contrast to Noah, but his own life is complicated by the fact that he has a son and an ex-wife in California. His decision to prioritize his son and move to California demonstrates his commitment to fatherhood, mirroring Ann’s growing dedication to her unborn child.

Though there is a mutual interest between Wes and Ann, their paths diverge. Wes’s departure underscores Ann’s need to focus on her new life as a mother and her relationship with her own family, rather than on rekindling a past romance.

Vinh

Vinh, though not present in much of the novel’s present-day narrative, looms large over Hương’s memories. As Hương’s abusive husband, he represents the violence and trauma that haunted her early adulthood.

His charm in the beginning of their relationship is quickly replaced by his violent temper, culminating in physical abuse that forces Hương to flee with Ann. Vinh’s violent confrontation at the Banyan House, where Minh kills him to protect her daughter and granddaughter, marks the most dramatic moment in Hương’s life.

Vinh’s presence as a specter of fear and trauma continues to influence Hương’s actions throughout the novel. His memory impacts her secrecy regarding his fate and her unwillingness to tell Ann the truth about her father.

Themes

Generational Trauma and the Inheritance of Secrets

The most prominent theme in Banyan Moon revolves around the complex inheritance of trauma, secrets, and unresolved histories across generations. The novel demonstrates how unspoken wounds and emotional scars pass down from one generation to the next, not just in the form of genetic or cultural heritage, but as deeply personal, psychological burdens.

Minh’s decision to conceal the truth about Hương’s father, as well as her participation in the violent act of killing Vinh, creates layers of silence and mistrust. These secrets, though born out of a desire to protect, lead to alienation between the women.

This estrangement echoes the broader experience of displacement and fragmentation caused by immigration and war, where personal histories are often too painful to fully confront. Hương’s inability to tell Ann the truth about her father echoes Minh’s silence, showing how trauma and shame can ripple through a family, shaping the lives of its members in unexpected ways.

By burning the photograph of Bình, Ann inadvertently perpetuates this cycle of hidden truths, even as she strives to break free from the burdens of the past.

The Interplay of Personal and Cultural Identity in Diasporic Experience

Banyan Moon delves deeply into the ways in which diasporic identities are formed at the intersection of personal history, cultural memory, and the immigrant experience. Minh’s journey from Vietnam to America after the war is not merely a geographical displacement but a cultural and existential one, as she must navigate the loss of her homeland and the need to recreate her sense of self in a foreign land.

For Ann, this manifests as a sense of cultural disconnection, exacerbated by her strained relationship with her mother and her American upbringing. Ann’s journey to rediscover her roots is both literal and metaphorical as she returns to the Banyan House, a place imbued with her family’s Vietnamese heritage, even as it stands in Florida.

The banyan tree itself symbolizes this connection to both land and culture, representing rootedness and the desire for belonging. The novel examines how these women negotiate their identities, balancing the pressures of assimilation with the need to preserve their cultural inheritance, which often involves confronting painful histories.

Mother-Daughter Relationships as a Reflection of Power, Sacrifice, and Emotional Distance

The strained and often painful relationships between mothers and daughters in Banyan Moon highlight the complexities of love, duty, and sacrifice. Thai intricately portrays the ways in which power dynamics between generations shape emotional intimacy.

Hương’s relationship with Ann is defined by resentment and distance, as Hương’s experiences of abuse, escape, and survival leave little room for tenderness or emotional vulnerability. In turn, Ann grows up feeling alienated from her mother, seeking love and stability elsewhere.

Minh’s role as both protector and enforcer of silence further complicates these dynamics. Her decision to kill Vinh and conceal the truth about Hương’s paternity is framed as an act of ultimate protection, yet it also isolates her emotionally from her daughter and granddaughter.

The novel suggests that the sacrifices mothers make for their children often come at the cost of their own emotional fulfillment. The power they wield over their daughters can be simultaneously nurturing and oppressive.

The Role of Memory, Ghosts, and the Supernatural in Navigating Personal and Collective Histories

Banyan Moon incorporates elements of the supernatural to explore how memory, both personal and collective, shapes identity and influences the present. Minh’s ghost serves as both a witness and a commentator on the actions of her daughter and granddaughter, symbolizing the inescapable presence of the past in their lives.

Her lingering presence in the Banyan House reflects how unresolved histories continue to haunt the living. The novel’s use of Vietnamese folklore, particularly the story of Chú Cuội and the magical banyan tree, underscores the importance of myth and memory in the construction of identity.

These stories serve as metaphors for the characters’ struggles with loss, healing, and the desire to hold onto things that are inevitably slipping away.

The banyan tree, in its connection to both Vietnamese cultural identity and the physical structure of the house, becomes a symbol of the past’s enduring grip on the present, even as the house is eventually destroyed in a fire. This mirrors the painful but necessary process of letting go.

The Paradox of Home as a Place of Comfort, Conflict, and Transformation

The Banyan House itself is a central motif in the novel, representing the complicated notion of “home” as both a refuge and a site of conflict. For Minh, the house is a symbol of her survival and success, a place she built through sheer determination and sacrifice.

However, for Hương and Ann, the house represents the weight of unspoken traumas and familial tensions. The act of clearing out the Banyan House becomes a metaphor for confronting the past, sifting through memories, and making space for new beginnings.

The fire that ultimately consumes the house marks a pivotal moment of transformation, where the physical embodiment of the family’s history is destroyed, allowing the characters to move forward. Yet, even in its destruction, the Banyan House lingers in their consciousness, as the characters must redefine their sense of home and belonging.

The cottage that Ann and Hương eventually move into suggests that while the past cannot be fully erased, it is possible to create new spaces for healing and reconciliation.

This theme speaks to the broader immigrant experience, where the concept of “home” is often fraught with contradictions—torn between the past and the present, the old world and the new.

The Tension Between Tradition and Modernity in Defining Womanhood and Autonomy

Throughout the novel, the female characters grapple with societal expectations and the tension between traditional roles and modern definitions of womanhood. Minh, Hương, and Ann represent three generations of women, each facing different challenges in asserting their autonomy.

Minh’s life is shaped by traditional Vietnamese values, where her worth is tied to her roles as a mother and a widow. Yet, she defies these expectations through her fierce independence and decision to take control of her own destiny by killing Vinh.

Hương, on the other hand, seeks to create a nuclear family that conforms to Western ideals, yet her marriage to Vinh and subsequent abuse underscore the limitations of these ideals.

Ann’s struggle for independence, particularly in her decision to leave Noah and reject traditional family structures, represents a more modern, Western conception of womanhood, yet she remains tied to the cultural expectations of her heritage.

The novel suggests that the path to autonomy is fraught with challenges, as each woman must navigate the competing demands of tradition and modernity in defining their identities.