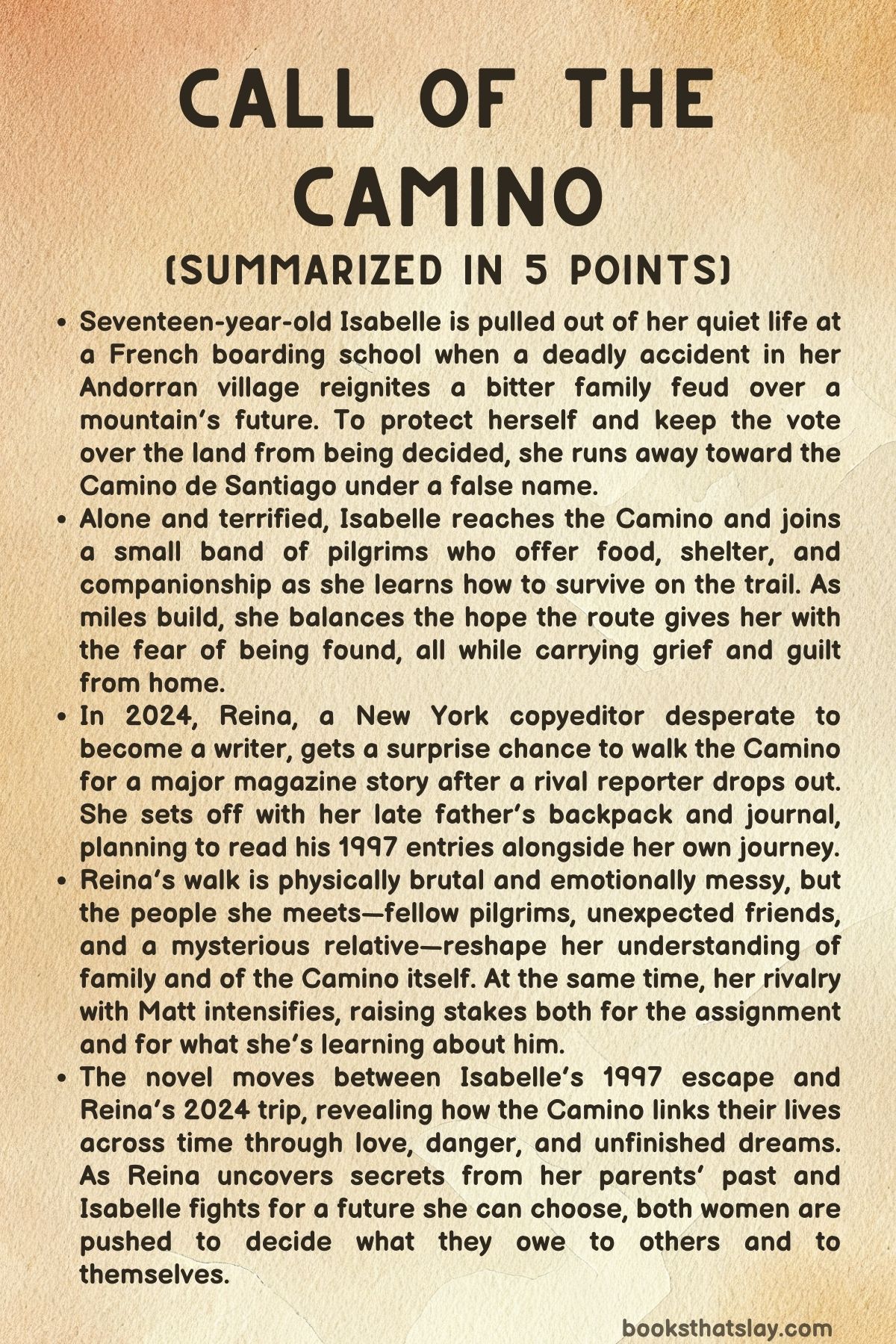

Call of the Camino Summary, Characters and Themes

Call of the Camino by Suzanne Redfearn is a dual-timeline novel set along the Camino de Santiago. One story follows Isabelle, a seventeen-year-old from an Andorran mountain village, who flees a deadly family feud in 1997 and finds fragile safety among pilgrims on the trail.

The other centers on Reina, a New York copyeditor in 2024 who unexpectedly walks the Camino for a magazine assignment and for the memory of her late father. As Reina reads her father’s journal day by day, the Camino becomes a bridge between past and present, revealing how a single journey shaped her family and offering her a new direction.

Summary

In 1997, Isabelle “Iz” is living at a Catholic boarding school near Pau, France, when her younger brother Xavier arrives with terrible news: Miguel and Manuel Sansas, twin boys from their Andorran village of Dur, have died in a car crash. Their deaths are not only tragic but dangerous.

Dur has been locked in a bitter dispute over a mountain. Isabelle’s father supports turning it into a ski resort; Señor Sansas, the twins’ father, wants mineral leases and a mine.

Years earlier the village vote ended in a tie. The deciding ballots belong to Isabelle and the twins once they turn eighteen.

With the twins dead, Isabelle’s single vote could determine the mountain’s future, and she fears Señor Sansas will see her family as responsible for the crash and seek revenge. Xavier warns that the Sansas men are coming to the school.

Isabelle realizes she may be killed to erase her vote and to punish her family.

Instead of returning home or running with Xavier, Isabelle chooses another path. She knows a legal loophole: the judge who set the vote date never required newly eligible voters to cast ballots by any deadline.

If Isabelle disappears and never votes, the tie remains forever and neither side wins. She believes this is her only protection and the only leverage she has against Señor Sansas.

With little more than determination, she runs into the woods and heads west toward the Camino de Santiago, trusting the old saying she learned in school that the Camino will provide for pilgrims.

Isabelle reaches St. Jean Pied de Port exhausted, hungry, and alone. She learns she needs a pilgrim passport to stay in hostels and to be recognized as a walker.

While waiting for the office to open, she begs a bakery owner for work and is given food and a blessing for the road. At the pilgrim office she meets three fellow travelers—Erika, Jen, and Joe—and introduces herself under an alias, “Joan,” to hide her identity.

They set out together across the Pyrenees. The climb is bruising.

Erika rages at the difficulty, Jen’s knee swells, Joe struggles with the weight of his pack, and Isabelle feels torn between relief at being away and grief for the home she may never see again. A veteran pilgrim named Dan and his daughter Emily join them, helping the group get over the pass and into Roncesvalles, where Isabelle is received kindly at the monastery despite having no money.

As the days pass, the Camino becomes both refuge and trial. Isabelle lies about who she is, but she opens to her companions in small ways—carrying Erika’s pack, sharing food, and laughing with them when spirits lift.

In Puente la Reina she prays for the dead twins and remembers her complicated feelings for Manuel, who once kissed her. There she meets two American brothers, David and Peter.

Peter is quiet but attentive. When Isabelle’s shoe rubs her toe raw, he cleans and bandages it and lends her sandals.

Their bond grows through conversation and shared miles. Isabelle senses she is falling for him, even as she knows she is living inside a false name.

The group shifts and thins. Erika quits early; Dan and Emily later separate to follow their own pace.

David flirts with Jen, easing her post-divorce sadness. Isabelle’s worn sneaker finally breaks apart near Cirauqui, and she stumbles and scrapes her knee.

When Peter appears holding new hiking boots he bought after backtracking many kilometers, Isabelle is stunned by his generosity. But danger follows her even here.

In Logroño she is broke and desperate enough to accept work cleaning an albergue. The hosteler assaults her the next morning.

Peter and the others return in time to stop it. Peter’s arm is fractured in the fight, and the attacker escapes before police arrive.

Terrified that authorities might uncover her real identity, Isabelle bolts to a cathedral, shaking with panic. David finds her and brings her back.

Later, away from town, Isabelle finally tells Peter the truth: she is Isabelle of Dur, seventeen, and being hunted because of the feud that killed the twins. Peter believes her and refuses to abandon her.

He also reveals a dream: to write a Camino guidebook. He asks her to help as translator and partner.

Isabelle accepts, letting his support cover her food and beds, and they continue together, now tied by love and by a shared project.

In 2024, Reina works as a copyeditor at Stellar Publications in New York, where the travel magazine Journey is being redesigned into single-destination issues. The August issue will focus on Spain and the Camino.

Reina wants to move into writing for better pay so she can support her struggling Aunt Robbie, and she timidly tells her hard-edged boss, Brenda Scythe, that she writes. At a staff meeting, Brenda assigns the major Camino feature to star writer Matt Calhoun, Reina’s office rival.

Matt declares he is going to walk the Camino himself. Soon after, he emails saying he was mugged and has lost his passport and laptop, delaying his travel.

Reina calculates he can’t meet deadlines and, driven by ambition and by a promise her late father once made to walk the Camino with her, volunteers to go in his place. Brenda accepts immediately.

Reina departs unprepared, carrying her father’s old Camino backpack and boots that aren’t made for distance. Inside the pack she finds her father’s pilgrim passport, old photo negatives, and a black journal that begins in St. Jean Pied de Port in June 1997.

She decides to read it entry by entry alongside her own walk, letting his words guide her. Day one nearly crushes her.

She struggles up the Pyrenees, gets blistered and overheated, and reaches Orisson barely standing. Canadian brothers Ted and Ned encourage her with humor and songs, and their kindness continues when they drain and bandage her blisters so she can keep going.

As Reina advances through villages and long empty stretches of the Meseta, she forms a trail family—Ted and Ned, a Scotsman named Gordon, a warm traveler named Tuck, and eventually Matt himself when he arrives to compete for the story. Reina’s knee swells, the heat wears her down, and Matt’s presence rekindles their rivalry.

In Puente la Reina, Reina reads a journal entry where her father describes meeting a copper-haired French girl called “Joan” whose shoes are falling apart. He writes about adoring her and wanting to help her.

Studying the old photos later, Reina realizes “Joan” is her mother and that her parents met on the Camino. The discovery changes the walk from assignment to inheritance.

Her father’s trail was not only a memory but the beginning of her life.

Conflict sharpens in Logroño when Matt hides the Wi-Fi password and causes Reina to miss a deadline. She vows to outrun him.

Yet over time his behavior doesn’t fit her old belief that he stole a colleague’s work. In Portomarín she rereads articles by her late coworker Karen and sees the truth: Matt had been ghostwriting to protect Karen as her health failed, keeping her employed and her reputation intact.

Reina is floored by how wrong she was. Uncle David—her father’s brother, missing for years—appears on the trail running a donativo oasis, and he confirms pieces of the past, including how Peter broke his arm protecting Reina’s mother decades earlier.

With David’s steady presence, Reina begins to forgive herself and to see Matt in a new light.

Reina’s personal life also shifts. Her boyfriend John flies in for her birthday and later proposes in León.

Swept up by the moment and by his reliability, she accepts. But after he leaves, the Camino’s honesty works on her.

She recognizes they want different lives, and she ends the engagement quietly before reaching the finish, not ready to explain it to anyone.

In the past, Isabelle’s freedom collapses in León when her father and Xavier track her down. She warns them that Señor Sansas will kill her, but her father insists on taking her home.

Isabelle escapes again, running into fields and vanishing north. Pilgrims Dan and Emily find her sick and alone, giving her money, clothes, and a plan to follow train tracks to the coast.

Isabelle’s condition worsens. She still risks herself to save orphaned kittens she finds near Ponferrada, then collapses with pneumonia and a partially collapsed lung.

A nurse named Eliana hides her with her son until she recovers. Isabelle calls her mother, who begs her not to return to Dur because it’s too dangerous.

Isabelle stays in exile in a Portuguese coastal town, working at a café under the name Joan Silva. When her father is later murdered in the feud, exile becomes permanent.

She accepts a marriage proposal from a good local man, Alberto, and writes Peter a farewell letter, sending repayment money and choosing safety over the life they imagined.

In 2024, Reina reaches Santiago with her friends, attends mass, and receives her Compostela. The trail family disperses.

Ted buys her a final night in a historic hotel, and Uncle David gives her a heavy box of her mother’s notebooks and research for Wisdom of the Way, the guidebook Isabelle, Peter, and David once planned but never finished. Reading it, Reina sees a path forward.

She copyedits Matt’s published Camino story overnight, sends her edits and photos to Brenda, resigns her job, and admits in a postscript that what happened between her and Matt wasn’t only about competition.

Instead of going back to New York, Reina travels to Dur. She meets her extended family, learns the feud has resolved over the years, and sees how the village now survives through both tourism and mining leases.

She decides to finish Wisdom of the Way as a real-time guide app, with Ted and Ned helping on the tech and business side. In the Dur tavern, Matt appears with a prepress magazine showing their shared byline.

He repeats her postscript, confesses his feelings, and kisses her as the villagers cheer. The Camino, which once saved her mother’s life and shaped her father’s future, now redirects Reina’s own, letting her claim both her history and her next step.

Characters

Isabelle “Iz / Izzy / Joan”

Isabelle is the emotional and moral spine of Call of the Camino, introduced as a seventeen-year-old who is already carrying more adult weight than she should. Her first decisive act—refusing to flee with Xavier and instead disappearing—shows a mind that evaluates consequences in a way her village’s feuding men cannot.

She is both deeply afraid and fiercely composed, using intelligence and symbolism (Joan of Arc’s words, the Camino as sanctuary, the alias “Joan”) to reclaim agency in a world where her body and vote are targets. On the trail she reveals a dual nature: outwardly capable, giving, and almost stubbornly resilient, while inwardly full of grief and yearning for home, family, and a life that has been stolen from her by the feud.

Isabelle’s kindness is not naïve; it is survival sharpened into empathy—carrying Erika’s pack, working for food, sweeping monasteries, and later risking herself to save orphaned kittens even when she is hunted and sick. Her arc is tragic-romantic: she finds tenderness and possibility with Peter, and even a creative future in their guidebook plan, but her past drags her back into exile.

The later choice to accept Alberto’s proposal and remain hidden after her father’s murder is not a betrayal of love but a hard-won accommodation to reality, showing the enduring mark of violence on her life. She becomes the “copper-haired angel” of her husband’s journal and thus the hidden origin of Reina’s own quest, linking generations through courage, loss, and the Camino’s promise of shelter.

Reina

Reina begins in 2024 as a careful, underestimated professional, more used to polishing others’ voices than claiming her own. Her longing to write is tied to love and duty—supporting Aunt Robbie, honoring her late father, and trying to step beyond a safe but narrowing role at Stellar Publications.

What makes Reina compelling is the tension between her practical self and her buried, pilgrimage-shaped self. She is impulsive enough to seize the Camino assignment, yet insecure about her body, skill, and right to be there.

The trail forces an unpeeling: blisters, heat, and exhaustion strip away persona until what remains is stubborn curiosity and a growing appetite for truth. Reading her father’s journal alongside her walk turns the Camino into a dialogue across time, and her discovery that “Joan” is her mother detonates her identity in the best way, converting a work trip into a personal reclamation.

Reina is also morally flexible in a human way—she starts with righteous hatred of Matt, then is humbled by learning the kindness beneath his reputation. Her engagement to John is less a triumph than a test of belonging; the Compatibility game and her quiet ending of the engagement show a woman learning to trust her own mismatch with a life she once assumed she should want.

By the end, Reina has shifted from editor to author, from follower to builder, choosing Dur and the unfinished guide project as a mission that fuses family legacy with her own voice. Her romance with Matt is not a fairy-tale reward but the byproduct of mutual stripping-down on the road, where she earns both love and authorship by refusing to stay small.

Peter

Peter enters Isabelle’s 1997 story as gentleness amid danger, a shy American pilgrim whose carefulness is revealed as strength rather than weakness. He is attentive in concrete ways—doctoring Isabelle’s feet, lending sandals, silently buying boots after a grueling backtrack—and these acts build trust faster than declarations ever could.

Peter functions as both protector and witness: he does not demand Isabelle be less complicated, nor does he try to “solve” her with pity. When the Logroño assault happens, his instinct is immediate and sacrificial, and the broken arm he carries afterward becomes a physical emblem of what he risks for her.

Importantly, Peter is also creative and future-facing; his proposal to write a guidebook with Isabelle is a quiet counterpoint to the village feud, choosing making over destroying. Yet his arc is also shaped by limits: he cannot defeat the politics surrounding Isabelle, and his love does not erase her need to disappear.

Still, his presence ripples forward through the journal, the unfinished Wisdom of the Way project, and David’s long exile, making him a foundational figure for the next generation’s story even when he is absent on the page.

Matt Calhoun

Matt begins as the archetypal workplace antagonist—talented, smug, and seemingly opportunistic—but the Camino reveals him as something far more layered. His decision to walk rather than simply report already hints that he is seeking meaning, not just a byline.

Through Reina’s eyes he is abrasive, competitive, and needling, yet his actions slowly dismantle that surface. The revelation that he has been ghostwriting for Karen reframes his ambition as loyalty: he protects a colleague’s dignity and career at cost to his own reputation, implying a private ethic that does not advertise itself.

On the trail he keeps needling Reina, but he is also consistently present at key moments, suggesting a mixture of attraction, guilt, and a desire to be seen truly. The line Reina glimpses in his journal about destiny and needing to “tell her” shows a man wrestling with vulnerability while still trapped in old armor.

By the end, Matt’s hostility has been transmuted into partnership—professionally through the shared byline and personally through confession and reunion in Dur. His arc moves from performative confidence to earned openness, making him a foil who becomes a mirror: he and Reina both arrive believing the Camino is about work, and leave knowing it is about identity.

Xavier

Xavier is Isabelle’s younger brother but carries the urgency of an older guardian in the opening crisis. He is the first messenger of catastrophe, racing to her school with fear in his body and clarity in his speech.

Xavier is pragmatic and protective, urging flight because he understands Dur’s logic of blood revenge. Unlike their father, Xavier can see beyond pride into consequence; he neither romanticizes the feud nor denies its deadly momentum.

After Isabelle disappears, his role becomes quieter but heavy—he is part of the family’s continuing peril and later becomes an uncle who welcomes Reina into Dur, signaling that he survives and participates in the hard reconciliation of the village. Xavier embodies loyalty without the arrogance of control, the sibling who tries to shield Isabelle while still respecting her mind enough to accept her choice when she refuses to run with him.

Gemma

Gemma is initially presented as Isabelle’s best friend at school, full of humor and warmth, and her farewell hug and declaration of love carry a poignant finality. She anchors Isabelle in ordinary girlhood at the exact moment that ordinary life collapses.

Her later reappearance in Portugal is crucial: Gemma becomes the personification of steadfast friendship, tracking Isabelle down, protecting her through an alias, and ensuring she receives medical care without being exposed. She is not a dramatic character, but she is a quietly heroic one—someone whose loyalty is practical, risky, and unromanticized.

Gemma represents the rare love that is not entangled in feud or romance, and her willingness to cross borders of danger for Isabelle underscores the theme that chosen bonds can be as life-saving as blood ties.

Dan

Dan is the veteran pilgrim who shepherds the 1997 group, acting as an emotional stabilizer on the terrifying first day over the Pyrenees. He is experienced enough to interpret the landscape and the group’s despair, and kind enough to let Isabelle cry without interrogation.

Dan’s presence is defined by calm authority—he does not dominate, but he steadily redirects panic into forward motion. When Isabelle is later found after fleeing León, Dan again fulfills a guardian role, giving her resources and a plan rather than judgment.

He stands for the Camino’s ethos of care between strangers, a secular-paternal figure whose help is offered without ownership.

Emily

Emily, Dan’s daughter, functions as a youthful echo of the Camino’s intergenerational spirit. She is less foregrounded than Dan but important in tone: her companionship softens the group, and her later choice to help Isabelle after León reinforces the theme that compassion is learned and transmitted.

Emily is a quiet counterweight to the violence in Dur, showing how a young person can be shaped by tenderness rather than rage.

Jen

Jen is initially one of Isabelle’s early Camino companions, carrying visible fatigue and pain, and later grows into a pivotal emotional ally. Newly divorced and worn down, she is not seeking grand meaning at first—she is simply trying to survive each day.

Yet her resilience deepens as she continues, and her relationship with David injects humor and flirtation back into her spirit. When the Logroño attack happens, Jen becomes fierce and maternal, calling police and trying to protect Isabelle’s safety and anonymity.

She represents adult womanhood recovering from fracture, and her presence shows Isabelle a model of survival beyond purity narratives or village expectations.

Joe

Joe travels with Isabelle’s 1997 group as a grounded, weary pilgrim whose endurance is quieter than others’ drama. He is not a romantic or ideological driver; instead, he demonstrates the Camino’s communal reality—people of different stories moving together because moving alone is harder.

His steady friendship helps keep Isabelle tethered to a human circle even while she is lying about her identity.

Erika

Erika begins as comic energy and then becomes the loud embodiment of the Camino’s tests. Her rage at the Pyrenees climb and temptation to quit make her honest, not weak; she says what others swallow.

Isabelle carrying her pack is both literal help and symbolic reversal, with the youngest and most endangered pilgrim supporting the one who feels least able to continue. Erika’s later decision to leave after Roncesvalles is not failure but a reminder that pilgrimage does not demand the same outcome from everyone, and her exit narrows Isabelle’s circle, intensifying the intimacy of those who remain.

David (Uncle David)

David is the hinge between timelines and one of the novel’s deepest studies of guilt and devotion. In 1997 he is the older brother walking with Peter, a lively participant in the early guidebook dream; his presence suggests a man of camaraderie and creative ambition.

His disappearance for seventeen years and reemergence as caretaker of the “Sanctuary of the Gods” reveals a life turned into penance and service. David has not escaped grief—he has arranged his entire existence around feeding and blessing pilgrims, repeating a daily ritual as if to keep alive what was lost.

When Reina finds him, he becomes both living archive and moral compass, explaining the past, correcting her misjudgments about Matt, and urging self-forgiveness. David embodies the Camino’s paradox: you can retreat from society and still be radically useful to strangers.

He is the surviving custodian of the unfinished Wisdom of the Way, and through him we see that love can persist as stewardship long after romance or family structures collapse.

Ted

Ted is one of Reina’s Canadian companions, a blend of humor, competence, and generosity. His practical care—draining and threading Reina’s blisters, pushing her forward with songs and jokes—establishes him as the kind of friend the Camino manufactures quickly.

Ted’s warmth helps transform Reina’s trip from competitive assignment to shared pilgrimage, and his later willingness to help build the guide app shows that his friendship is not confined to the trail. He represents the social alchemy of the road: strangers who become collaborators in a new life.

Ned

Ned, Ted’s brother, walks primarily for health, and his vulnerability makes him quietly inspiring. He is not portrayed through grand speeches but through effort: the daily discipline of walking, enduring heat, and leaning on companionship.

His presence widens the novel’s idea of pilgrimage beyond spiritual or romantic motives. Ned’s partnership with Ted also models supportive brotherhood, giving Reina an example of male care that is noncompetitive and safe.

Gordon

Gordon, the jokey Scotsman, supplies levity and grit during Reina’s hardest stretches, especially on the Meseta. His role in games, songs, and teasing becomes a psychological survival tool, keeping monotony from eroding morale.

Yet he is not only comic relief; his political argument with Ted and the lingering prickliness afterward show that Camino community is not utopian. Gordon is a realistic friend—funny, flawed, and still loyal enough to stay walking beside Reina when others bus ahead.

Tuck

Tuck is part of Reina’s smaller Meseta cohort, reinforcing the theme of companionship in emptiness. His presence helps form a temporary “family” of four with Reina, Matt, and Gordon, a crucible where tensions and sympathies intensify.

Tuck is less individually detailed than others, but he functions as social glue and witness, helping make the Meseta feel like a shared endurance rather than solitary punishment.

John

John is Reina’s New York boyfriend and later fiancé, and he is characterized by steadiness that becomes misalignment. His surprise arrival for Reina’s birthday is genuinely loving, and he fits easily into the pilgrim group, showing he is not selfish or shallow.

But his refusal to enter León Cathedral and his disastrous Compatibility mismatch with Reina quietly expose a deeper gap in values and curiosity. His public proposal is sincere, yet it lands in a space where Reina is already evolving beyond their shared script.

John’s role is not to be a villain but to represent a good life that is nonetheless the wrong life, helping Reina understand that decency is not the same as destiny.

Aunt Robbie

Aunt Robbie is Reina’s anchor back home and one of the clearest expressions of interdependence in the modern timeline. Her financial struggles motivate Reina’s career hunger, but her emotional support is equally important—she helps pack, steadies Reina’s panic, and acts as family after the father’s death.

Aunt Robbie represents the unglamorous love that makes big leaps possible, and her presence keeps Reina’s ambitions tethered to care rather than ego.

Brenda Scythe

Brenda is Reina’s formidable boss, a gatekeeper figure who embodies institutional power and the difficulty of being seen in a workplace. She is sharp, demanding, and not overtly nurturing, yet she is fair enough to accept Reina’s bold request to take the Camino assignment.

Brenda functions as a catalyst: without her pragmatism and willingness to gamble on Reina, the modern pilgrimage never happens. She symbolizes the professional world Reina outgrows, and her receipt of Reina’s final email marks Reina’s shift from subordinate to self-authoring creator.

Señor Sansas

Señor Sansas is the feud’s living engine, a man shaped by land politics into vengeance. He is less a nuanced psychological portrait than a social force—representing Dur’s inherited logic that honor must be defended through blood.

His potential pursuit of Isabelle makes her flight necessary, and his collision with Isabelle’s family reveals how communal disputes become personal wars. Even after his direct presence fades, he remains the shadow on Isabelle’s choices, the reason she cannot safely return even when she longs to.

Miguel and Manuel Sansas

The Sansas twins are mostly absent physically but dominate the plot as an explosive absence. Their deaths break the political deadlock and ignite the revenge threat that drives Isabelle onto the Camino.

For Isabelle they are not only symbols of feud but boys she knew, mourned, and loved in complicated ways, especially Manuel, whose kiss becomes a haunting memory of the life she might have lived in Dur. The twins embody how youthful futures are consumed by adult conflicts, and their death is the story’s original wound.

Carlos

Carlos, a cousin of the Sansas family, appears as immediate danger when Isabelle sees him searching for her. He is a reminder that the feud is not abstract; it has foot soldiers.

Carlos’s presence forces Isabelle deeper into hiding and accelerates her commitment to the Camino as the only safe corridor.

Eliana

Eliana is the nurse mother who shelters Isabelle when she collapses with pneumonia. She represents an ordinary goodness that becomes extraordinary in crisis—offering safety, secrecy, and care to a hunted girl she barely knows.

Eliana’s apartment is a temporary sanctuary paralleling the Camino’s hostels, reinforcing the theme that compassion is a form of pilgrimage too.

Alberto

Alberto is the stonemason who courts Isabelle in exile and later proposes. He is kind, decent, and offers stability rather than passion, giving Isabelle a lifeline when her past has made romance with Peter impossible.

Isabelle’s acceptance of Alberto is a survival choice wrapped in tenderness; Alberto thus represents the possibility of building a new life not out of grand dreams but out of steady mutual care.

Carolina

Carolina, the café owner where Isabelle works during recovery, functions as another quiet rescuer. She provides work, community, and a place for Isabelle to exist under a false name without constant fear.

Carolina symbolizes the restorative side of exile—how a displaced person can find temporary belonging through labor and shared routine.

Liam

Liam is Reina’s best friend, appearing early as a practical and emotional supporter. His role in preparing Reina and helping her access her father’s backpack frames him as someone who believes in Reina before she fully believes in herself.

Liam’s presence shows that Reina’s courage is not solitary; it is nourished by friends who hold her up at the moment of leap.

Karen

Karen is Reina’s late coworker whose Cat Story articles and decline become a hinge in Reina’s re-evaluation of Matt. Though absent in the present, Karen’s legacy reveals the moral complexity of professional relationships: her dignity was protected through Matt’s secret ghostwriting.

She represents the vulnerabilities behind public work and the quiet kindness that can exist inside competitive industries.

Cami

Cami is part of Reina’s Camino circle, helping form the social fabric that keeps Reina walking. Her overhearing of the broken engagement and her continued presence underline how quickly intimacy forms on pilgrimage, where private lives become shared terrain.

Cami represents that communal closeness—sometimes comforting, sometimes exposing.

Nicole

Nicole appears as a fellow pilgrim with her own budding relationship with Matt. Her affectionate reconciliation with him after conflict complicates Reina’s view of Matt by showing how he exists in someone else’s tenderness too.

Nicole functions as a subtle mirror for Reina, suggesting that love on the Camino is messy, public, and shaped by walking side by side through strain.

Aunt Ana

Aunt Ana is part of Dur’s welcoming family network when Reina arrives in Andorra. She represents the healed future of a village once broken by feud, offering Reina both belonging and context.

Through Aunt Ana and the extended family, Reina sees that Dur has evolved, letting her claim the place not as a haunted origin but as a living home.

Isabelle’s Father

Isabelle’s father is a study in pride and consequence. His support of the ski resort plan and the feud with Señor Sansas place his children in mortal danger, yet he is not depicted as uncaring; he believes he can control the fallout and protect Isabelle once he drags her back from León.

That belief is tragic hubris, and his later murder proves how little protection pride can offer. He represents a generation that mistakes domination for duty, and his death seals Isabelle’s exile.

Themes

Pilgrimage as a way to remake the self

Isabelle’s flight onto the Camino is not framed as a romantic adventure but as a survival gamble. She steps onto the trail because every other route back into her life is blocked by threat, family history, and the deadly math of a tied vote.

What begins as disappearance turns into a harsh education in endurance. Hunger, cold, foot injuries, and constant fear strip away any soft ideas she once had about home or duty.

The trail forces her to learn how to accept help without revealing herself, how to keep moving while grieving, and how to decide who she wants to be when the identity she was born into has turned dangerous. Decades later, Reina arrives with a different kind of crisis: a stalled career, financial pressure, and an old ache linked to her father’s unfinished promise.

Her early misery on the climb out of St. Jean Pied de Port makes clear she is not walking to prove toughness or chase a brand assignment; she is walking because she needs a reset that her normal life cannot offer. The Camino asks both women to live day by day, reducing life to steps, meals, sleep, and the next village.

That simplicity becomes a mirror. For Isabelle, it reveals courage she didn’t know she had and shows her that running away can also be an act of protection and moral resistance.

For Reina, it reveals how much of her self-image was built around other people’s expectations, especially her boss’s approval and her boyfriend’s steadiness. On the Meseta, the repeated routine and empty horizon push her inward until she can no longer hide from her doubts about love, ambition, and grief.

By the time Reina reaches Santiago, walking has shifted from an assignment to a personal rite, and she emerges willing to resign, travel to Dur, and choose a life that fits her rather than one she has inherited. The pilgrimage theme in Call of the Camino insists that movement through space can be movement through fear, shame, and unfinished love, and that transformation is not sudden inspiration but the slow, stubborn act of continuing.

Family legacy, hidden origins, and the search for identity

Two timelines echo each other to show how identity is shaped by what families say, what they hide, and what history leaves behind. Isabelle carries her family name like a target.

The feud in Dur has defined her father’s worldview and claimed her adolescence, even while she is away at school. When the twins die, Isabelle realizes that her vote has become a lethal symbol, and her family story is no longer a private burden but a public sentence.

She tries to escape being reduced to that single role by taking the alias “Joan,” yet the alias is not only camouflage; it is a test of who she might be without the village’s expectations. Her longing for home continues to pull at her, which shows that identity is not something easily shed.

Reina’s identity problem is quieter at first, but just as intense. She believes she knows who her parents were: a father who walked the Camino, a mother rooted in the present, and a past that is closed.

The discovery that her father’s journal describes “Joan,” and that “Joan” is her mother, unseals that past. It reframes her own life as the product of a trail romance, exile, and unfinished work.

Reading the journal in sync with her steps becomes a kind of dialogue across time. Reina is not only learning about her parents; she is learning the parts of herself that came from them, including her stubbornness, her capacity for risk, and her drift toward stories.

The arrival of Uncle David in the donativo oasis deepens this theme. A missing family member reappears not as a broken remnant but as someone who has built a meaningful life around service, and his presence links Reina to her father’s world in a living, complicated way.

Family legacy in Call of the Camino is not presented as destiny that traps people, nor as a heritage to worship. It is something to decode.

Isabelle ultimately cannot return to her family without danger, so she builds a new branch of legacy in exile. Reina, after learning what created her family, chooses to return to Dur and finish the guide her parents started.

The book argues that identity comes from both blood and choice, and that knowing the truth about where you came from can be the first step toward deciding where you will go.

Feud, violence, and the moral weight of choice

The Andorran feud is more than background; it is a study in how communal conflict turns private lives into battlegrounds. Isabelle’s father and Señor Sansas are not simply stubborn rivals; they represent competing visions of progress, pride, and control over shared land.

The tied vote shows how a small community can reach a deadlock that hardens into obsession. When Miguel and Manuel die, the feud shifts from politics into vengeance, and Isabelle becomes a proxy for adult hatred.

Her decision to vanish is a moral act under pressure. She refuses to let her vote become a weapon for either side, and she recognizes that choosing not to choose can be the only way to protect lives.

That refusal complicates easy ideas about courage. She is not saving herself alone; she is trying to stop a cycle that would consume her siblings and perhaps the village.

The violence that follows—threats, pursuit, her father’s later murder—shows the price of such cycles and how they keep demanding new sacrifices. In the 2024 timeline, open violence is rarer, but the theme persists in subtler forms: career sabotage, manipulation, and the harm caused by assumptions.

Matt’s hiding of the Wi-Fi password is petty compared to murder, yet it mirrors the same impulse to win at another person’s expense. Reina’s belief that Matt stole Karen’s work is another kind of inherited feud, built from resentment and incomplete facts.

The book uses these parallels to show that conflict is not only a matter of guns or fists; it also lives in workplaces, friendships, and the stories people tell about each other. Crucially, resolution comes not through a single hero but through time, negotiation, and the exhaustion of hatred.

Dur eventually thrives through both tourism and mining leases, implying that the village found a compromise that the older generation could not imagine. The dangerous ski run named for Reina’s grandfather suggests that the past is remembered but no longer rules the present.

In Call of the Camino, choice is always heavy. Some choices are forced, some are refused, and some are delayed until a community is ready.

The theme warns how easily pride and fear can turn ordinary disputes into blood debts, but it also leaves room for repair when later generations decide that survival matters more than victory.

Community, generosity, and the ethics of strangers

The Camino is portrayed as a moving society with its own ethics, where people who owe each other nothing still keep each other alive. Isabelle survives because the trail’s culture makes kindness ordinary: a bakery woman feeds her without suspicion, a monastery welcomes her despite her lack of money, pilgrims share burdens, and Dan quietly gives space for grief.

Even when Isabelle is hiding, she is repeatedly met with help offered as a default human response. This generosity is not sentimentalized.

She still encounters cruelty and danger, including assault in Logroño and the constant threat of being found. But the help she receives forms a counterweight to the violence that pushed her onto the trail in the first place.

It teaches her that belonging can be built through actions rather than bloodlines, and that moral life can exist outside the rules of Dur. For Reina, community begins as convenience—companions who pass time with games and songs—then becomes an emotional anchor.

Ted and Ned literally tend her wounds, and later the Meseta’s monotony is made bearable by shared rituals. The birthday picnic in Terradillos is a high point of this theme.

These people organize food, laughter, and presence for someone they have known only on the road, celebrating her simply because she is part of their temporary family. John’s arrival at that moment exposes an important contrast.

He fits in socially, but his proposal later feels out of tune with the deeper rhythm of the trail, which is about growth rather than performance. Uncle David’s donativo oasis expands the theme into philosophy: he has turned his life into steady service, asking nothing fixed in return.

The ethical logic of the Camino becomes clear there—care is offered first, repayment is optional, dignity is preserved. Even the story of Portomarín being moved brick by brick foreshadows how communities protect what matters through collective effort.

By the end, Reina’s plan to build a real-time Wisdom of the Way app with fellow pilgrims shows community extending beyond the walk into shared purpose. In Call of the Camino, strangers do not magically solve each other’s problems, but they create safe moments where healing becomes possible.

The theme suggests that a person can be carried by others without losing agency, and that the smallest acts—coffee at dawn, a bandage, a spare bed—can change the direction of a life.

Love, forgiveness, and second chances

Romance in the book is not treated as an escape from hardship but as something that grows inside it. Isabelle and Peter’s bond forms through physical vulnerability and shared trust: he cleans her injured toe, buys her boots at real risk to himself, and later protects her during the attack.

Their love is built in the open air of the trail, where lies are harder to keep and kindness shows quickly. Yet the story refuses an easy happy ending.

Isabelle’s exile, her sickness, her father’s death, and the danger of return force her to choose survival over reunion. Her farewell letter is a painful kind of love: she repays what she can, tells the truth, and releases him.

That choice turns love into sacrifice rather than possession. In Reina’s timeline, love is also tested against reality.

Her relationship with John is stable and well-meaning, but the Compatibility game and the cathedral moment reveal their mismatch in values and curiosity. Her acceptance of his proposal comes from emotion and gratitude, yet the Camino continues to change her, and she ends the engagement because she cannot build a future on comfort alone.

This is not portrayed as betrayal but as an evolution into honesty. The more surprising love story is Reina and Matt’s.

Their rivalry carries years of bitterness, and Reina’s assumption about Karen’s ghostwriting shows how resentment can distort perception. When she learns Matt’s truth, the theme of forgiveness becomes central.

She must forgive him for being abrasive, forgive herself for misjudging him, and forgive the past for not being what she thought. Their eventual reunion in Dur works because it is not based on conquest or grand gestures, but on mutual recognition and shared work.

Love appears again in Uncle David’s devotion to pilgrims and in the villagers’ cheering embrace at the end, showing affection as communal as well as romantic. Second chances in Call of the Camino are not handed out by fate; they are created through confession, endurance, and the willingness to let go of old narratives.

The book’s closing movement—Reina choosing to finish her parents’ guide, Matt acknowledging his feelings, Dur welcoming her home—shows forgiveness as a doorway into new life, not a denial of harm.