Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will Summary and Analysis

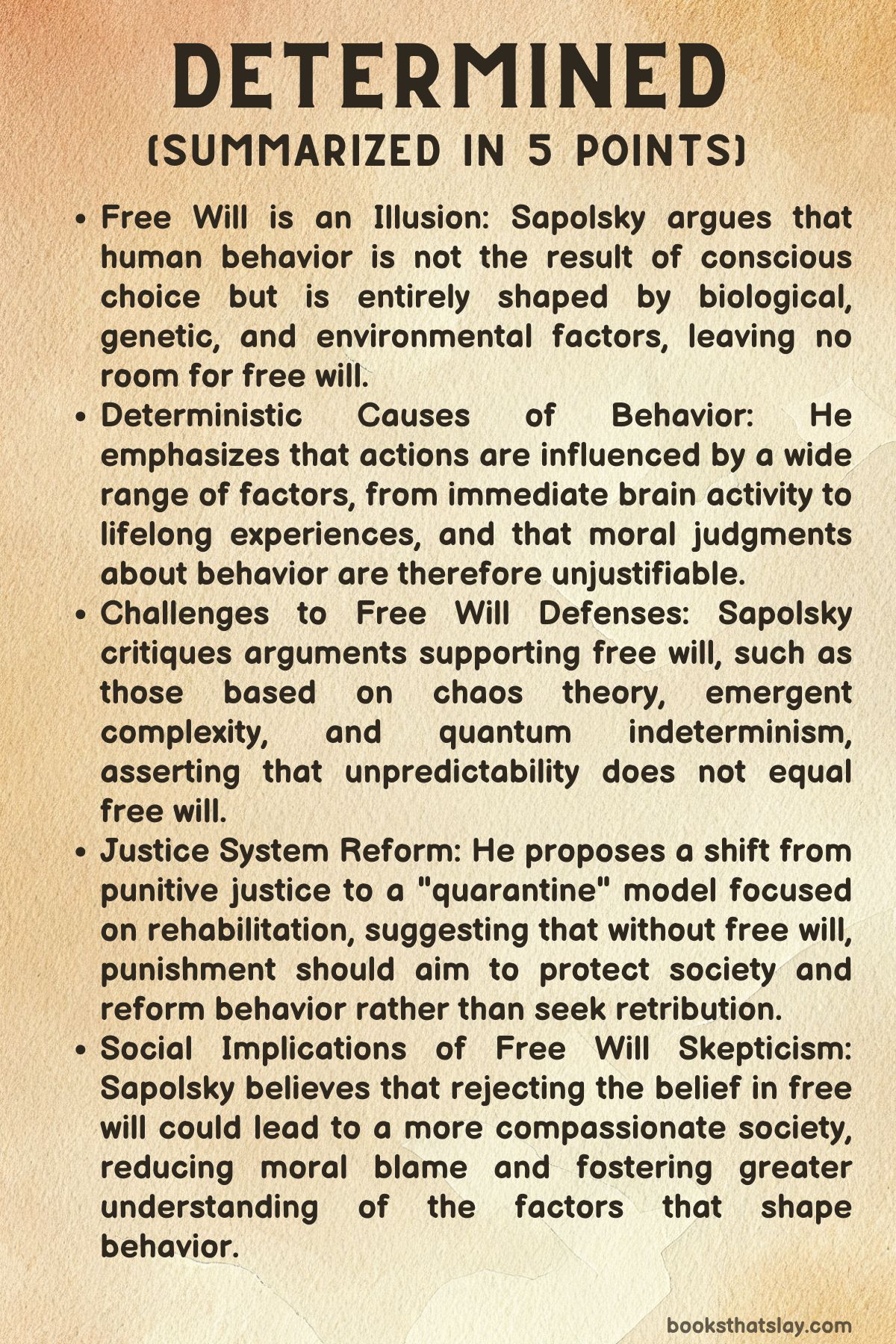

Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will by Robert Sapolsky is a thought-provoking exploration of human behavior, arguing that free will is an illusion. Sapolsky, a prominent neuroscientist, takes an interdisciplinary approach, blending biology, psychology, and philosophy to explain how our actions are shaped by factors beyond our control—such as genetics, environment, and brain activity.

He claims that accepting the absence of free will can reshape societal systems like justice and reduce harmful moral judgments. The book aims to encourage a more compassionate understanding of human behavior through a lens of determinism.

Summary

In Determined Robert Sapolsky builds a compelling case for the idea that human behavior is entirely determined by biological and environmental influences, leaving no room for the traditional concept of free will.

He begins with a metaphor, likening the world to a stack of turtles, where each layer represents a different causal factor influencing behavior.

According to Sapolsky, people’s actions are not the result of conscious choice but are driven by a complex web of causes that extend far beyond their control. Given this perspective, moral judgments about human behavior become both illogical and unfair.

One of the key elements in the free will debate is the brain’s decision-making process. Sapolsky discusses Benjamin Libet’s experiments, which revealed that the brain exhibits signs of activity before individuals are consciously aware of their decisions.

While these findings support his view that free will is an illusion, Sapolsky argues that Libet’s work is too narrow.

He asserts that behavior isn’t just influenced by immediate brain activity but by a lifetime of experiences and conditions—spanning from seconds to years in the past—that shape who we are.

Sapolsky also takes aim at the philosophical arguments of Daniel Dennett, who believes that while circumstances may differ, people possess the freedom to rise above their challenges. Sapolsky counters this by arguing that luck, both good and bad, compounds over time.

He cites the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) score, which demonstrates how childhood trauma increases the likelihood of negative behavior later in life.

This correlation, he says, undermines the notion of free will, showing how factors beyond an individual’s control—genetics, upbringing, and even prenatal environment—affect decisions.

The book explores more complex scientific ideas like chaos theory, emergent complexity, and quantum indeterminism, all of which are sometimes used to argue in favor of free will. Chaos theory, for example, reveals that while certain systems may appear unpredictable, they are still governed by deterministic rules.

Similarly, emergent complexity, seen in natural systems like ant colonies, appears chaotic but is the result of simple rules followed by individual components.

While unpredictability may seem like freedom, Sapolsky insists that it is not evidence of free will.

As for quantum indeterminism, Sapolsky addresses the idea that free will might be rooted in the unpredictable nature of quantum effects. However, he refutes this by arguing that quantum randomness is either canceled out or too chaotic to lead to the kind of deliberate choice we associate with free will.

In the latter half of the book, Sapolsky considers the implications of a life without free will, particularly in the realm of justice.

He advocates for a “quarantine” model, similar to Norway’s humane prison system, where wrongdoers are treated in ways that prioritize rehabilitation over punishment.

He believes that eliminating moral blame would reduce unnecessary suffering and lead to a more compassionate society.

Ultimately, Sapolsky suggests that abandoning belief in free will doesn’t make life bleak or meaningless.

Instead, it can foster a more tolerant and understanding society, one where people are judged less harshly for factors beyond their control and where systemic issues, like inequality and social biases, can be addressed more effectively.

Analysis

The Intricate Interplay of Biological and Environmental Determinants of Human Behavior

Sapolsky’s argument in Determined hinges on the idea that human behavior is the result of a complex, finely interwoven matrix of biological and environmental influences, both operating on immediate and long-term scales.

This theme moves beyond simplistic notions of nature versus nurture, offering instead a sophisticated model where genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors form an elaborate web that determines human action.

Sapolsky’s exploration of the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) score exemplifies this, demonstrating how traumatic experiences in childhood profoundly shape later behavioral patterns. He emphasizes that behavior cannot be understood as the result of conscious choice or free will because it is continually shaped by an infinite string of preceding conditions.

Factors like the prefrontal cortex’s structure and function, which influence decision-making, are themselves the product of countless antecedent causes, reaching back to genetic inheritance, prenatal conditions, and childhood experiences.

Thus, the concept of free will becomes illusory, as human behavior emerges not from conscious choice but from this ceaseless causal chain of biological and environmental factors.

The Illusion of Free Will as a Philosophical and Societal Construct: Rebutting Daniel Dennett

A significant portion of Determined engages in a rigorous critique of philosophical proponents of free will, particularly Daniel Dennett, who argues that individuals possess the agency to overcome their circumstances.

Sapolsky counters this by highlighting the compounding nature of luck and environmental influence over time, suggesting that individuals who are born into disadvantage cannot simply “choose” their way out.

Through empirical studies and a methodical deconstruction of free will’s philosophical underpinnings, Sapolsky shows that behavior is not a matter of personal choice but is shaped by an array of factors beyond one’s control.

He challenges Dennett’s notion that luck eventually balances out, demonstrating instead how the accumulation of luck—and misfortune—grows more influential over time.

The implication is that free will is not just philosophically untenable but also socially damaging because it fosters a moral judgment system that unjustly holds individuals accountable for circumstances far outside their control.

In this sense, Sapolsky uses his critique to expose the fallacy of meritocratic and moral systems that blame or reward individuals for behavior that is in fact determined by complex causal mechanisms rather than personal agency.

The Fallacies of Unpredictability and Determinism in Quantum Mechanics and Chaos Theory as Proxies for Free Will

A key thematic investigation in Sapolsky’s work is his rejection of scientific arguments that attempt to salvage free will through misinterpretations of quantum mechanics and chaos theory.

By unpacking the relationship between unpredictability and determinism, Sapolsky demonstrates that while chaotic systems are unpredictable, they are not free from causal determination.

In this sense, chaos theory, which explains how small changes in initial conditions can result in vastly different outcomes, does not provide room for free will. Rather, it only highlights the complexity of deterministic systems.

Sapolsky extends this argument to quantum mechanics, a field often co-opted by free will proponents due to the inherent randomness observed at subatomic levels. Yet Sapolsky dismantles this association by showing that quantum randomness does not bubble up to influence macroscopic human behavior in any significant way.

Even if randomness exists at the quantum level, it is not something that humans can “tap into” to exercise free will.

Furthermore, the notion that randomness could provide the foundation for free will is itself paradoxical, as random behavior would hardly constitute the kind of intentional, agent-driven action that free will advocates champion.

Therefore, Sapolsky renders these scientific phenomena as tangential and ultimately irrelevant to the question of free will, refuting any possibility that science could provide a basis for its existence.

The Ethical and Societal Implications of Free Will Skepticism on Moral Judgment and Criminal Justice

One of the book’s most provocative themes revolves around the ethical consequences of accepting that free will does not exist. Sapolsky makes the case that moral judgment becomes indefensible when behavior is understood as determined rather than chosen.

If human actions are not freely willed but the result of biological and environmental forces, holding individuals morally accountable for their behavior is irrational.

This has profound implications for the criminal justice system, which is based on the notion of retributive justice—punishing individuals because they are deemed morally responsible for their crimes.

Sapolsky suggests that a more rational and humane approach would be to adopt a quarantine model, akin to the Norwegian prison system, where individuals who exhibit harmful behavior are isolated and rehabilitated without being subjected to punitive measures.

This approach would recognize that criminal behavior stems from deterministic causes rather than personal failing, and it would prioritize reducing recidivism through rehabilitation rather than enacting retribution.

Sapolsky thus calls for a reimagining of justice systems, where empathy and understanding replace punishment, and where individuals are not judged for actions they had no control over.

This radical shift in societal norms would require widespread acceptance of free will skepticism, yet Sapolsky believes such a transformation is both necessary and possible, as historical shifts in the understanding of conditions like epilepsy and schizophrenia have already demonstrated.

The Paradox of Meaning and Morality in a World Without Free Will: A Rejection of Nihilism

One of the central anxieties many people have when confronting the idea that free will may not exist is the fear that life would become devoid of meaning, purpose, and moral structure. Sapolsky addresses this concern head-on, arguing that the absence of free will does not necessarily lead to nihilism.

Instead, he posits that a deterministic understanding of human behavior can actually enhance our capacity for compassion, empathy, and ethical conduct.

By eliminating the moral judgment that comes from believing in free will, society could foster a more just and tolerant world, where individuals are not blamed for characteristics or behaviors over which they have no control.

Sapolsky draws an analogy between free will skepticism and atheism, suggesting that just as atheists are capable of leading moral lives without belief in a higher power, so too can individuals act ethically without the belief in free will. The reduction of blame and the increase in empathy would create a more harmonious and equitable society.

Rather than rendering life cold and meaningless, Sapolsky envisions a world in which accepting determinism actually enriches human relationships and societal structures, freeing people from the burden of self-blame and unjust moral condemnation.

The Transformative Power of Education, Social Reform, and Behavioral Understanding in a Post-Free Will Society

Sapolsky concludes with an optimistic vision of how society could transform by embracing free will skepticism. By understanding human behavior through the lens of biology and environment, societal ills such as poverty, crime, and social inequality could be addressed at their root causes.

Education systems could be reformed to account for the biological and environmental determinants that influence learning and behavior, leading to more personalized and effective teaching methods.

Social policies could shift towards preventing crime and antisocial behavior by addressing their underlying causes, such as childhood trauma and economic deprivation, rather than focusing solely on punishment.

Sapolsky’s model also suggests that behavioral interventions could be more scientifically grounded, leading to more effective strategies for modifying harmful behaviors.

This potential for large-scale societal reform underscores the book’s ultimate message: rather than clinging to the myth of free will, society could move toward a more humane, scientifically informed approach to governance, justice, and social welfare.